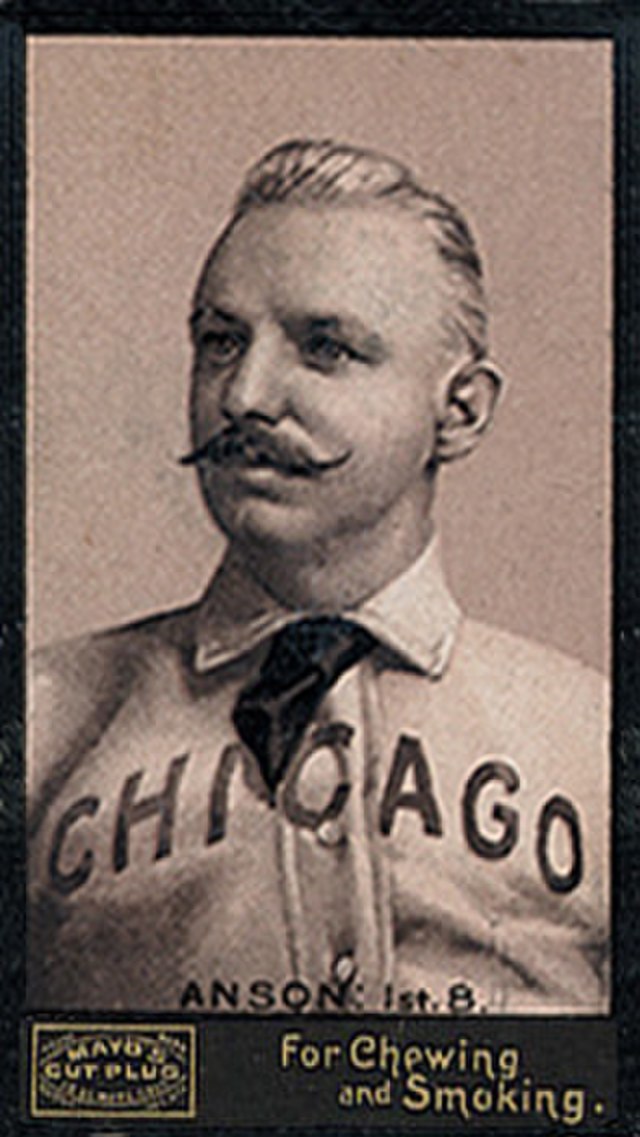

Cap Anson Stats & Facts

Baseball is the only game you can watch on the radio. Join the community today and listen to hundreds of broadcasts from baseball’s golden age.”

Sign Up or learn more

[mepr-login-form use_redirect=”true”]

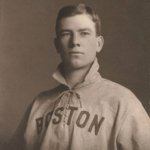

Cap Anson Essentials

Positions: First Base

Bats: R Throws: R

Weight: 227

Born: April 17, 1852 in Marshalltown, IA USA

Died: April 14, 1922 in Chicago, IL USA

Debut: May 6, 1871

Last Game: October 3, 1897

Hall of Fame: Inducted as a Player in 1939 by Old Timers

Full Name: Adrian Constantine Anson

Baseball is the only game you can watch on the radio. Join the community today and listen to hundreds of broadcasts from baseball’s golden age.”

Sign Up or learn more

[mepr-login-form use_redirect=”true”]

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1871

Cap Anson

Al Spalding

Bobby Mathews

Deacon White

Ezra Sutton

Ross Barnes

George Wright

Harry Wright

Levi Meyerle

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology for Cap Anson Career

Biography

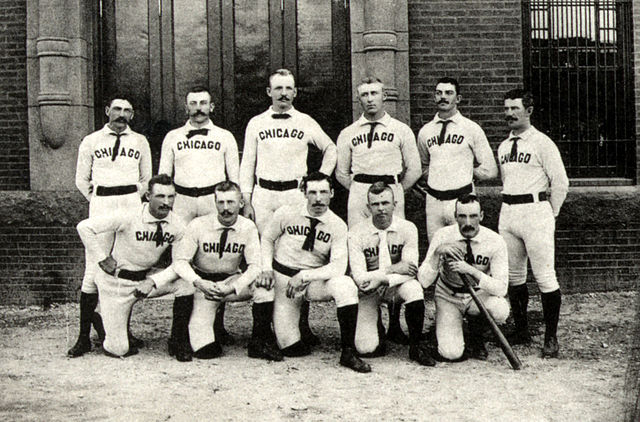

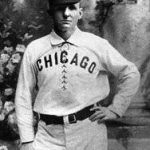

Baseball’s first great star, Cap Anson led the Chicago Cubs to five National League pennants while serving as the team’s player-manager. In the process, Anson established himself as arguably the 19th century’s finest hitter. However, the Hall of Fame first baseman’s legacy is diminished greatly by the fact that he was also an outspoken supporter of excluding blacks from professional baseball.

Adrian Constantine Anson was born on April 17, 1852 in Marshalltown, Iowa, a town founded by his father. Anson was a boisterous youth who displayed little interest in schoolwork. Knowing he wanted to be a ballplayer at an early age, Anson served as the second baseman for his hometown team, the Marshalltown Stars, by the time he turned 15. With his father playing third base, and his older brother Sturgis in center field, the club won the Iowa state championship in 1868.

Two years later, the Forest City team of Rockford, Illinois, a well-known minor-league club in the National Association, came to Marshalltown for a two-game matchup against the local nine. Though the visitors won both contests, Adrian Anson impressed the opposition enough to prompt Forest City to offer him a contract.

Anson opened the 1871 campaign with his new club, at a salary of $65 per month. The 19-year-old hit .325 that year, before signing on with the Philadelphia Athletics, another National Association team, at season’s end.

Anson spent the next four seasons with Philadelphia, splitting his time mostly between first and third base, while establishing himself as one of the team’s best hitters. In 1874, manager Harry Wright of the National Association’s Boston Red Stockings led his club and the Athletics on a mid-season trip to England that featured a series of exhibition games between the two teams. During the three-week tour, Anson formed a friendship with Boston’s star pitcher Albert Spalding that ended up impacting the remainder of his career.

Anson headed west in 1876 to play for the Chicago White Stockings of the National League, a new circuit in its first season. He hit .356, while his friend Albert Spalding served as both manager and pitcher for the club, which won the National League’s inaugural pennant.

Anson enjoyed another fine season in 1877, hitting .337 while playing both third base and catcher. He hit .341 the following year, striking out only once in 261 at-bats after moving to the outfield. After Anson was named the club’s captain and manager in 1879, the nickname “Cap” was born. As one of his first decisions, Anson made himself Chicago’s regular first baseman.

Although Anson was a big man for his time, standing 6′ 0″ and weighing 227 pounds, he did not possess a great deal of power at the plate. Line-drive singles were his trademark, and he was highly skilled at hitting the ball to specific areas of the field. He remained exceedingly difficult to strike out: in 9,104 big-league at-bats, he fanned only 294 times, an average of just once in every 31 trips to the plate.

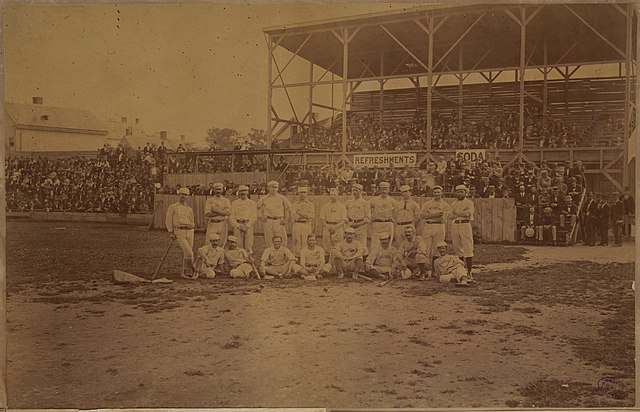

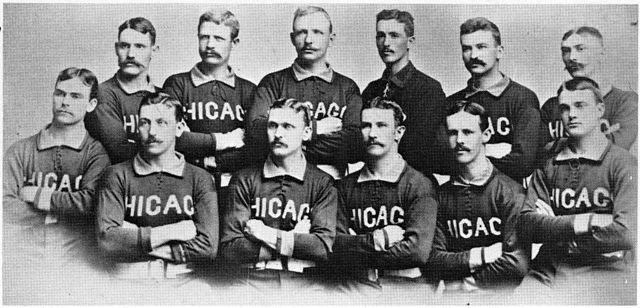

The White Stockings won the National League pennant in 1880, beginning a run of five championships in seven years. As manager, Anson ran the club with an iron hand. He imposed strict training rules, and he disciplined players for drinking, missing curfews, and being overweight. A man with a volatile temper, he intimidated umpires and could be a merciless bench jockey to opponents.

Yet Anson was also a shrewd and innovative manager. In 1880, he became one of the first field generals to alternate pitchers from one game to the next, creating an early version of the “starting rotation.” He developed the practices of using a third-base coach, having fielders back up one another, and flashing signals to hitters. During the first half of the 1880s, he introduced an aggressive base-stealing strategy that pressured opponents into making errors, and he pioneered new hit-and-run plays. Anson devised a training routine that included swinging Indian clubs, skipping rope, punching a heavy bag, and playing handball. He and Albert Spalding are also credited with the idea of sending a team to a warmer southern climate for pre-season workouts. In 1885, the White Stockings made the first such “spring training” trip.

In 1881, Anson guided the Chicago club to its second consecutive championship. He had perhaps his greatest season as a hitter, winning his first batting title with an average of .399, and leading the National League in hits (137), total bases (175), and RBIs (82). The league played a far more limited schedule in this early era: Anson did not appear in as many as 100 games until 1884, when he was 32 years old. His highest total of games played in a season, 146, occurred in 1892, at age 40.

The White Stockings won the pennant again in 1882, with Anson leading the National League in RBIs for the third consecutive season. The combination of baseball’s growth in popularity and Anson’s outstanding playing ability and handsome physical appearance made the Chicago first baseman the sport’s first national celebrity.

Unfortunately, though, Anson shared the widespread racial prejudice of his day. In 1883, he threatened to cancel an exhibition game between the White Stockings and the minor-league Toledo Blue Stockings because Toledo’s catcher, Moses Fleetwood Walker, was African-American. Anson backed down only when the Toledo club’s manager informed him that the White Stockings would forfeit the gate receipts if they refused to play. In 1887, Anson objected to facing the Newark Little Giants in an exhibition game when he discovered the opposing team planned to start African-American George Stovey on the mound. When the Newark club finally agreed to substitute a white player for Stovey, Anson allowed his team to take the field. Since Anson was an extremely influential man throughout his playing career, his intolerant attitude regrettably went a long way towards creating the unspoken ban against black players that existed in baseball for the next six decades.

In 1885 and 1886, the White Stockings won the final two pennants of Anson’s tenure as manager. Anson’s play continued to thrive, as he batted .371 during the 1886 campaign, while also driving in a league-leading 147 runs in 125 games.

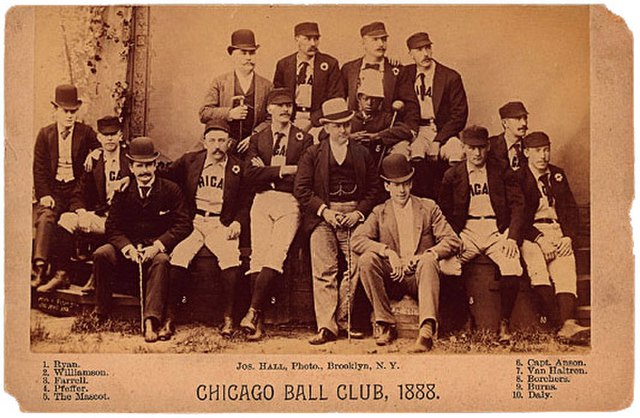

When the 1888 season concluded, White Stockings president Albert Spalding took his team and a collection of star players from other National League clubs on a ballplaying tour around the world. During the six-month trip, the two squads played exhibition games in Egypt, Ceylon, New Zealand, Australia, and Europe. The tour proved to be the high-point of Anson’s life, with his account of the journey taking up nearly half of the autobiography he later wrote.

By 1889, Anson owned a considerable amount of stock in his club, holding a 13% ownership interest. One of the few National League stars who didn’t sign with the Players League in 1890, he bitterly criticized those players who did as “traitors.” When many White Stockings veterans jumped to the upstart circuit that year, the team replaced them with younger players. In tribute to its youth movement, the club subsequently earned the nickname “the Chicago Colts.”

Anson hit .291 in 1891, the first time in his 16 National League seasons that he failed to hit .300. Nevertheless, he led the league in RBIs for the eighth and final time of his career, with a total of 120. At 39 years of age, though, his range in the field had become limited.

Fielding gloves were common in the National League by the mid-1880s, but Anson had stubbornly resisted wearing one, remaining the last bare-handed first baseman in the majors. He finally began using a glove in 1892, at age 40. Though he still holds the career record for errors by a first baseman, his high total is largely attributable to the great length of his career, the poorer infield conditions of early baseball, and the fact that he played bare-handed for his first 16 years in the major leagues. In fact, he led National League first basemen in fielding percentage five times.

Despite his advancing years, Anson hit remarkably well in 1894, batting .388 at the age of 42 and driving in 100 runs in only 84 games. He had also mellowed enough to become a fatherly figure to his teammates, often being called “Pop” by many of them.

Still, Anson was the oldest player in the National League, leading to a gradual decline in his offensive production over the course of the next several years. The Colts, who hadn’t won a pennant since 1886, continued to struggle. Anson, a longtime advocate of sobriety, had an increasingly difficult time relating to the hard-drinking players he managed, who began to resent his inflexible command. After hitting .331 in 1896 at age 44, Anson slipped to .285 in 1897, with Chicago finishing in ninth place.

On October 3, 1897, the Colts wrapped up the season with a doubleheader against St. Louis. On what turned out to be Anson’s last day as a major-league player, he hit two home runs in the first game. He remains the oldest player (at 44) ever to hit .300, and the oldest man (45) to homer twice in a game.

At season’s end, Albert Spalding, who held controlling ownership in the Colts, and Jim Hart, the club’s president, declined to renew Anson’s contract. Spalding offered to hold a testimonial benefit for his old friend, in the hope that he might raise $50,000 as a going-away tribute to the man who had given so much to his team. But Anson refused the gift, saying that it smacked of charity, and suggesting that accepting it would “stultify my manhood.”

In June of the following season, New York Giants president Andrew Freedman hired Anson to manage his club, promising him full control of the team. But Freedman continually interfered in personnel and management issues, prompting Anson’s stint as manager to end just one month later, with a record of 9-13.

In his 22 seasons in the National League, Anson batted over .300 on 19 separate occasions, posting a career batting average of .331 in the process. When he retired, he held the major-league records for hits, runs (1,722), doubles, (529), and RBIs (1,880). More than 100 years after he played his last game for the Chicago club that later became the Cubs, he still holds the franchise records for career RBIs, runs, hits, singles, doubles, and putouts.

Although Anson is credited with being the first major league player to compile 3,000 hits, a considerable amount of controversy has arisen over the years as to the exact number of hits he actually accumulated during his career. When the first edition of Macmillan’s Baseball Encyclopedia was published in 1969, it disregarded a rule in place only for the 1887 season that counted walks as hits and times at-bat. Anson’s 60 walks were removed from his 1887 hits total, resulting in a career mark of 2,995. However, later additions of the Encyclopedia credited him with five additional safeties, placing Anson’s total at an even 3,000.

The other controversy over Anson’s hits total involved the five years he played in the National Association. Neither the Macmillan Encyclopedia editions nor Major League Baseball itself at that time recognized the NA as being a true major league. Only recently has Major League Baseball accepted the NA as a de facto major league; the MLB.com website now includes the NA years in Anson’s record, placing his major league hits total at 3,418.

Other sources credit Anson with a different number of hits, largely because scoring and record keeping remained haphazard in baseball until well into the 20th century. Beginning with the publication of the Baseball Encyclopedia, statisticians have continually found errors and have adjusted career totals accordingly. According to the Sporting News baseball record book, which does not take National Association statistics into account, Anson amassed 3,012 hits over the course of his career. On the other hand, the National Baseball Hall of Fame (which uses statistics verified by the Elias Sports Bureau) credits Anson with 3,081 hits. This figure disregards any games he played in the National Association, but includes the walks he earned during the 1887 campaign as hits.

Anson’s managerial career was similarly impressive. His 1,288 victories and five pennants exceeded any other 19th century manager.

After leaving baseball, Anson experienced his fair share of struggles, although he initially fared rather well. In 1899, he opened a bowling and billiards emporium in downtown Chicago. The business proved successful. With the help of ghostwriter Richard Cary, Jr., he wrote his memoir, “A Ball Player’s Career.” Published in 1900, the book is considered the first baseball autobiography.

However, Anson later embarked on a number of other business ventures that proved far less successful, including opening a handball arena and producing a bottled ginger beer that ended up exploding on store shelves. In 1905, he was elected City Clerk of Chicago. But later that year a need for cash prompted him to sell his remaining stock in the Chicago ballclub, ending his 29-year association with the team.

After serving one term as City Clerk, Anson lost a 1907 Democratic primary bid to become sheriff of Cook County. That same year, he acquired a semi-pro baseball team in the Chicago City League that he named “Anson’s Colts”, and for whom he subsequently built a ballpark on the city’s South Side. But the team didn’t draw well in his three years as owner, and he ended up losing quite a bit of money. However, it is noteworthy that the club played many games against the Chicago Leland Giants, the leading African-American team of the era, with no apparent objection from Anson.

After declaring bankruptcy in 1910, Anson rejected the National League’s offer to assist him by providing him with a pension. For a number of years, he supported himself by acting in vaudeville, finally retiring from the stage in 1921. Anson died the following year, on April 14, 1922, just three days shy of his 70th birthday, after suffering from a glandular ailment. He was interred at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago.

On June 12, 1939, Anson and his former friend Albert Spalding were inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee. Anson’s Hall of Fame plaque states: “Greatest hitter and greatest National League player-manager of 19th century.”

Charles Comiskey, whose 44-year career as a major-league player, manager, and club owner extended from the National League’s first decade until 1931, said of Anson, “He was the greatest batter that ever walked up to hit at a baseball thrown by a pitcher. I have seen them all from his day to this. I played against him and I know.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Baseball is the only game you can watch on the radio. Join the community today and listen to hundreds of broadcasts from baseball’s golden age.”

Sign Up or learn more

[mepr-login-form use_redirect=”true”]

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

A seminal figure in the growth of organized baseball, Cap Anson was a superstar in the 19th century. A hard-hitting slugger and an innovative first baseman, Anson led the National League in runs batted in eight times, and copped two batting titles. As a dominant force in the birth of the Senior Circuit, Anson’s bigotry contributed to the exclusion of blacks from the game, but as historian Bill James has observed, his persuasive personality also helped save the league from fracture in the early going. After an amazing 27-year career as a player, player/manager, and manager, Anson retired to Chicago in 1898. He was one of the first men inducted into the Hall of Fame, in 1939.

Played For

Rockford Forest Citys, National Association (1871)

Philadelphia Athletics, National Association (1872-1875)

Chicago Cubs (1876-1897)

Managed

Philadelphia Athletics, National Association (1875)

Chicago Cubs (1879-1897)

New York Giants (1898)

Similar: Anson is a one of the most unique players and characters in the history of baseball.

Linked: Moses Fleetwood Walker

Post-Season Appearances

1885 World Series

1886 World Series

Where He Played: First base

Minor League Experience

1870: Marshalltown (Indiana League)

Anson, Racism, and the Color Barrier

The first white child born into a town his father founded, in a slave state nearly a decade before the Civil War, Adrian Constantine Anson was shaped by his environment. By the time he was a teenager, he was a bigot, and those warped attitudes led to an infamous showdown in Toledo, Ohio, in August of 1883.

Anson’s White Stockings scheduled an exibition game against the minor league Toledo team for August 10. When Anson arrived, he learned that Toledo’s catcher, Moses Fleetwood Walker, was black. Unaware that Walker was not scheduled to start the game, Anson refused to play the contest with Walker in uniform. When Toledo’s manager heard of this, he defiantly inserted Walker into center field for the game and threatened Anson with legal action to recoup the gate receipts. Anson capitulated, but he secured an agreement the following season, that ensured that Walker and his brother, Welday, would not be on the field to play his club.

This incident is often cited as the genesis for the unofficial ban of backs from major league baseball. But the truth is far more complicated. In order for blacks to be barred, team owners, league officials, the press, and government officials had to conspire and fail to act. Anson, certainly a racist, is not solely responsible for the color barrier that existed from the mid-1880s until Jackie Robinson’s debut in 1947, but he didn’t help.

Best Strength as a Player

Hitting for power.

Largest Weakness as a Player

Intolerance.

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.