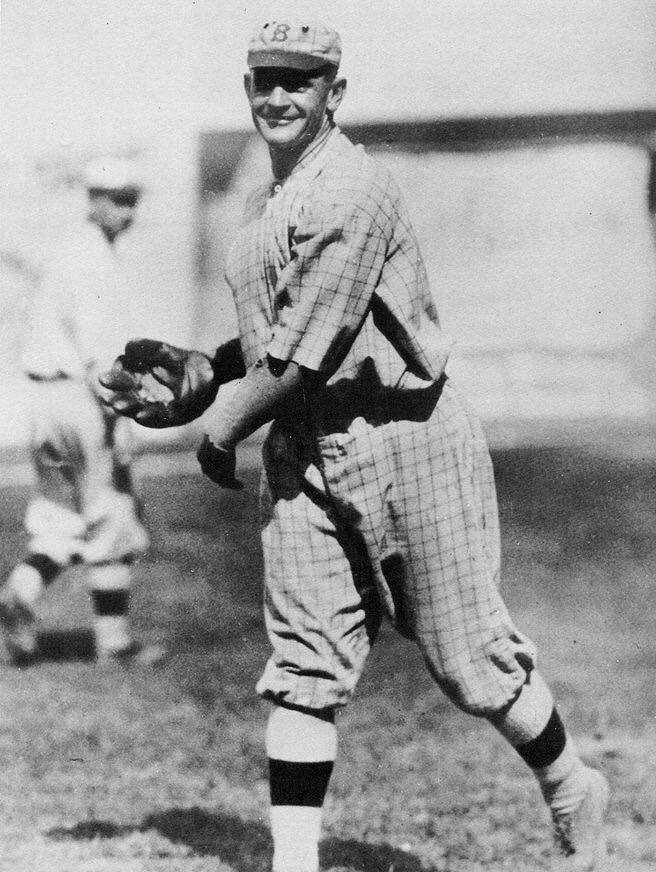

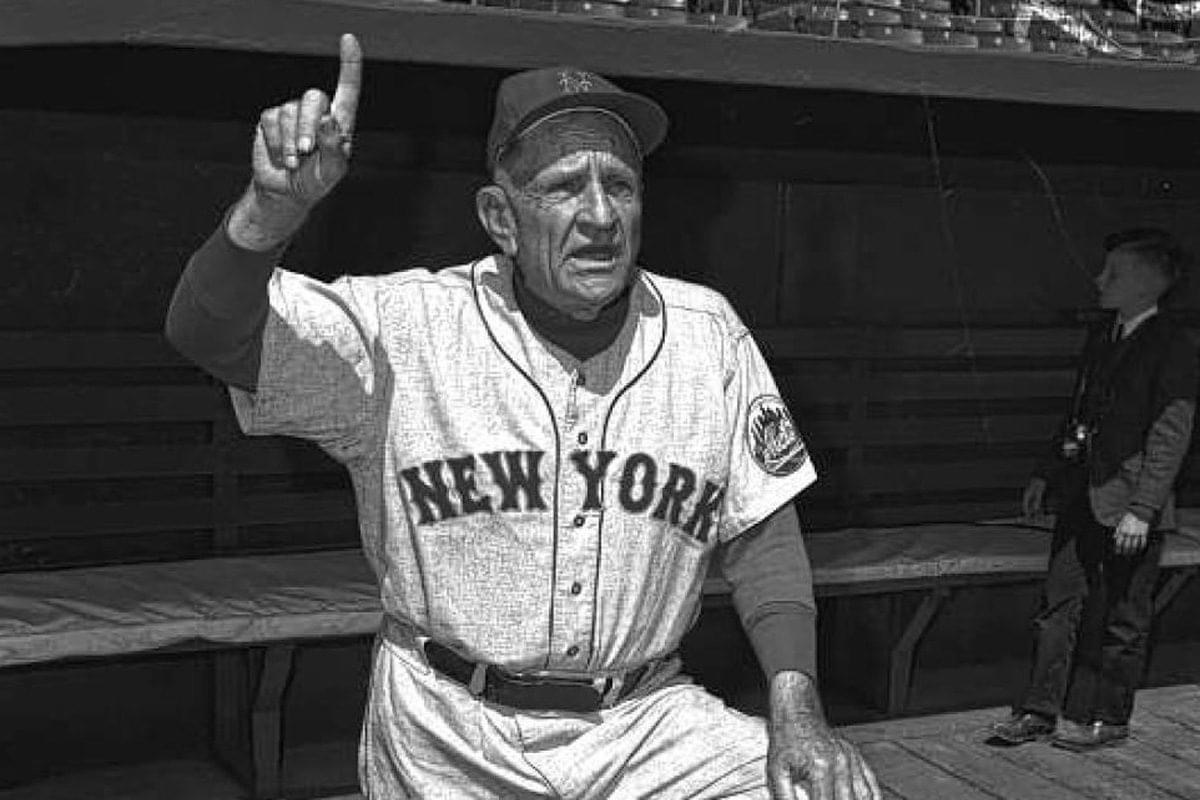

Casey Stengel Stats & Facts

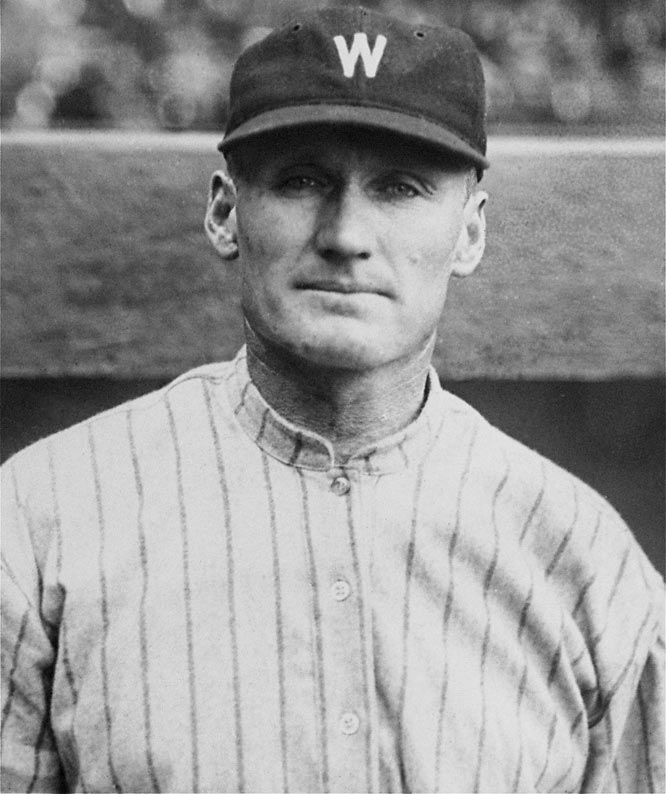

Casey Stengel

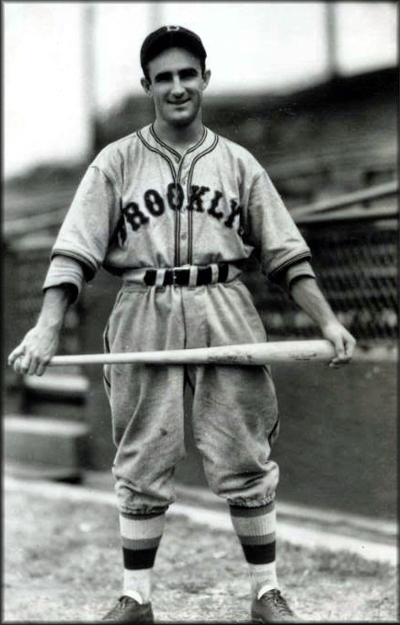

Position: Rightfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Left 5-11, 175lb (180cm, 79kg)

Born: July 30, 1890 in Kansas City, MO

Died: September 29, 1975 in Glendale, CA

Buried: Forest Lawn Memorial Park, Glendale, CA

High School: Central HS (Kansas City, MO)

Debut: September 17, 1912 (3,817th in major league history) vs. PIT 4 AB, 4 H, 0 HR, 2 RBI, 2 SB

Last Game: May 19, 1925 vs. CIN 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Manager in 1966. (Voted by Veteran’s Committee) View Casey Stengel’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Charles Dillon Stengel

Nicknames: The Old Perfessor

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1912

Rabbit Maranville

Cy Williams

Del Pratt

Bobby Veach

Ray Schalk

Casey Stengel

Buck Weaver

Ray Chapman

Herb Pennock

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology

Biography

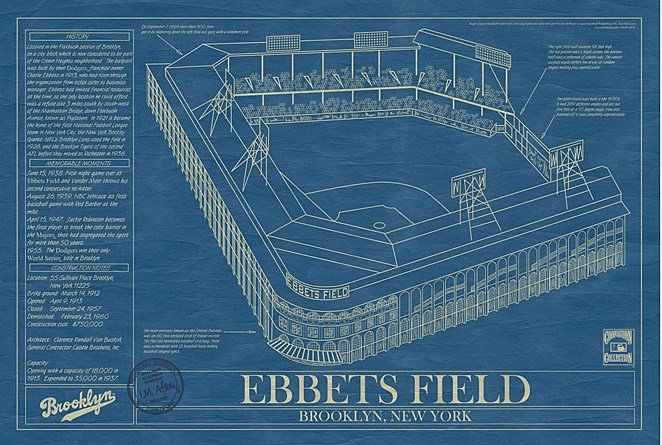

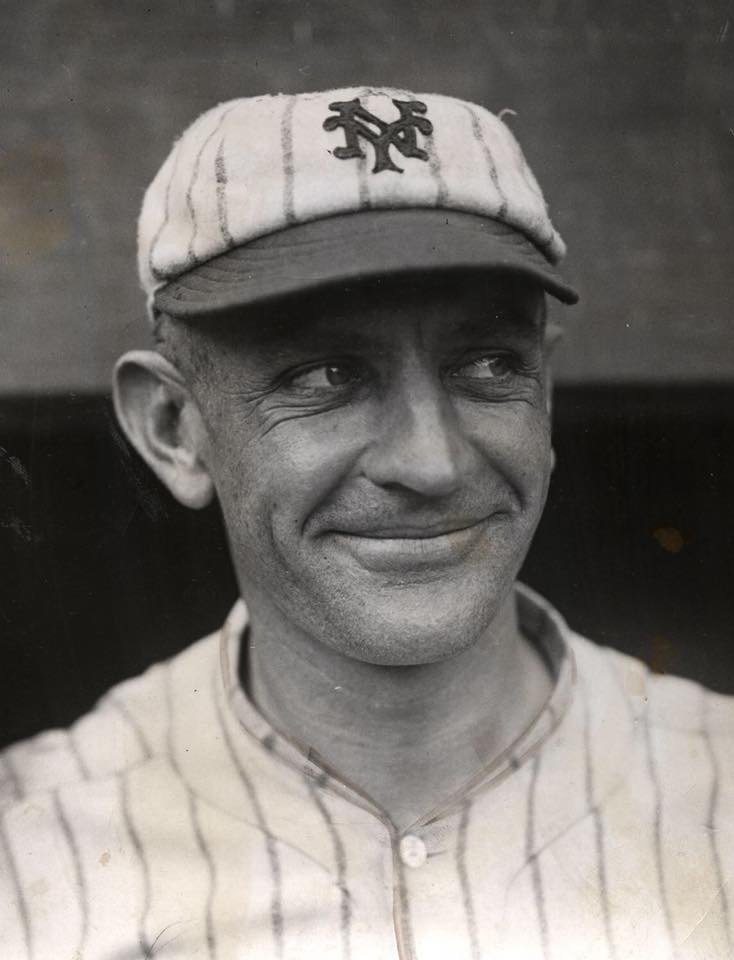

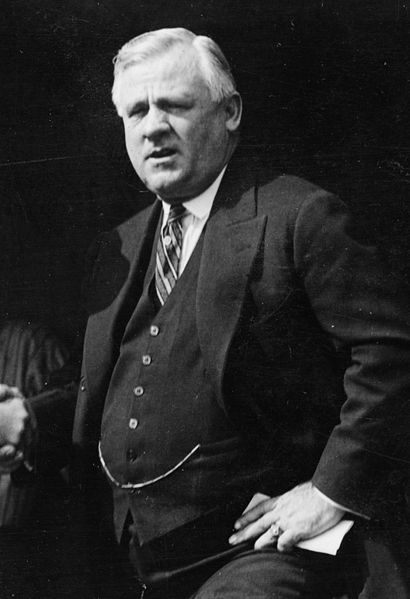

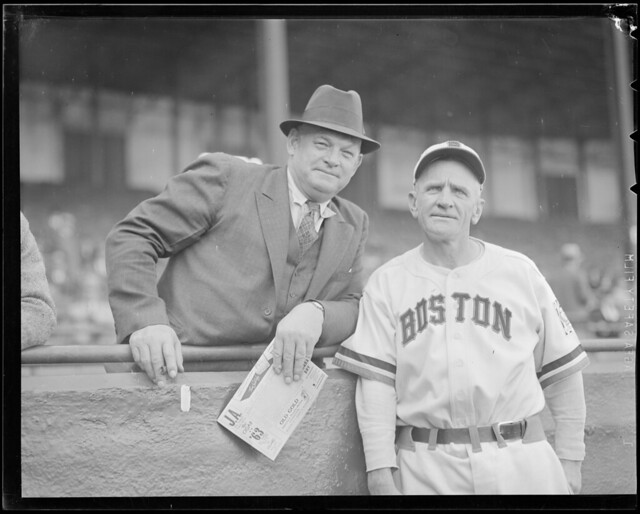

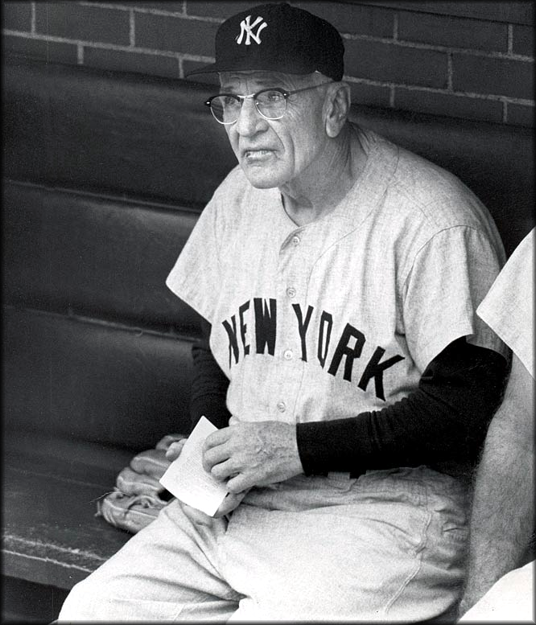

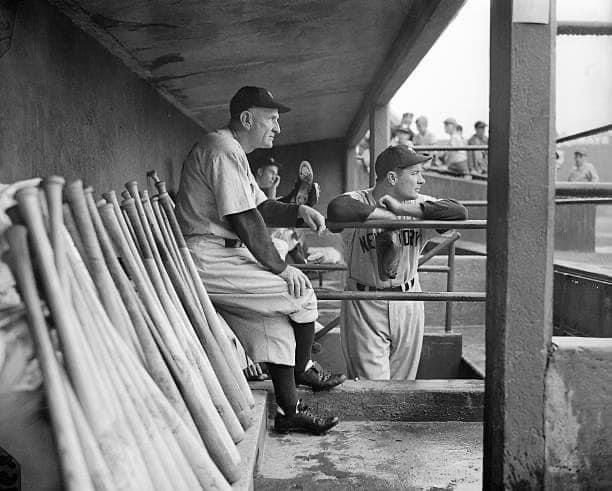

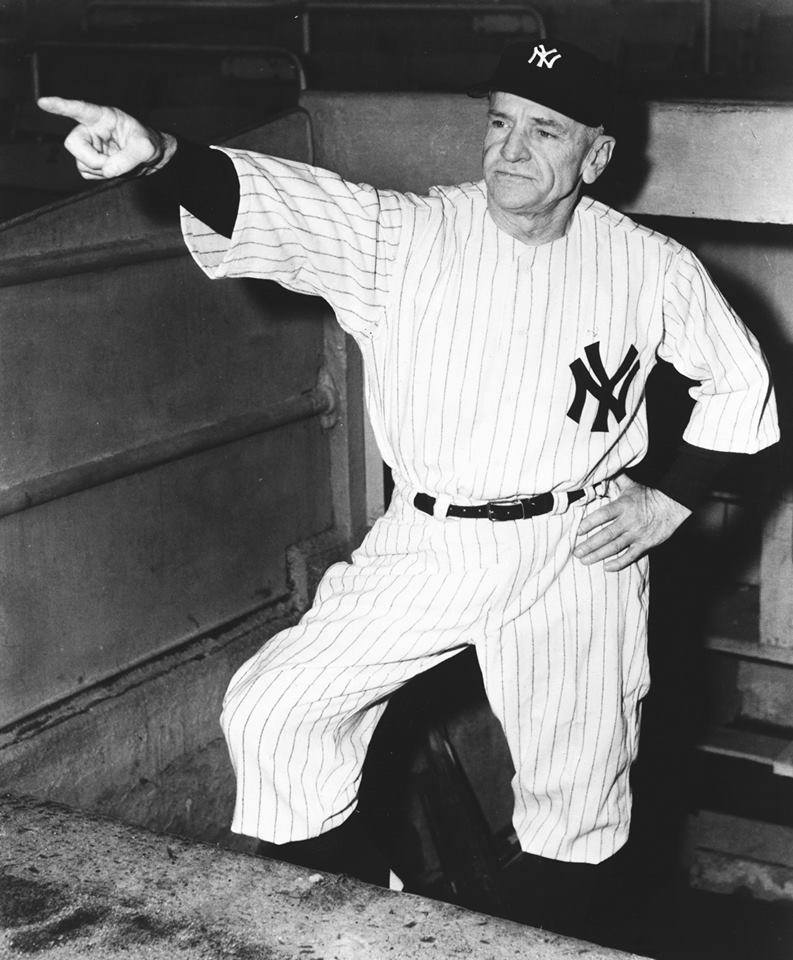

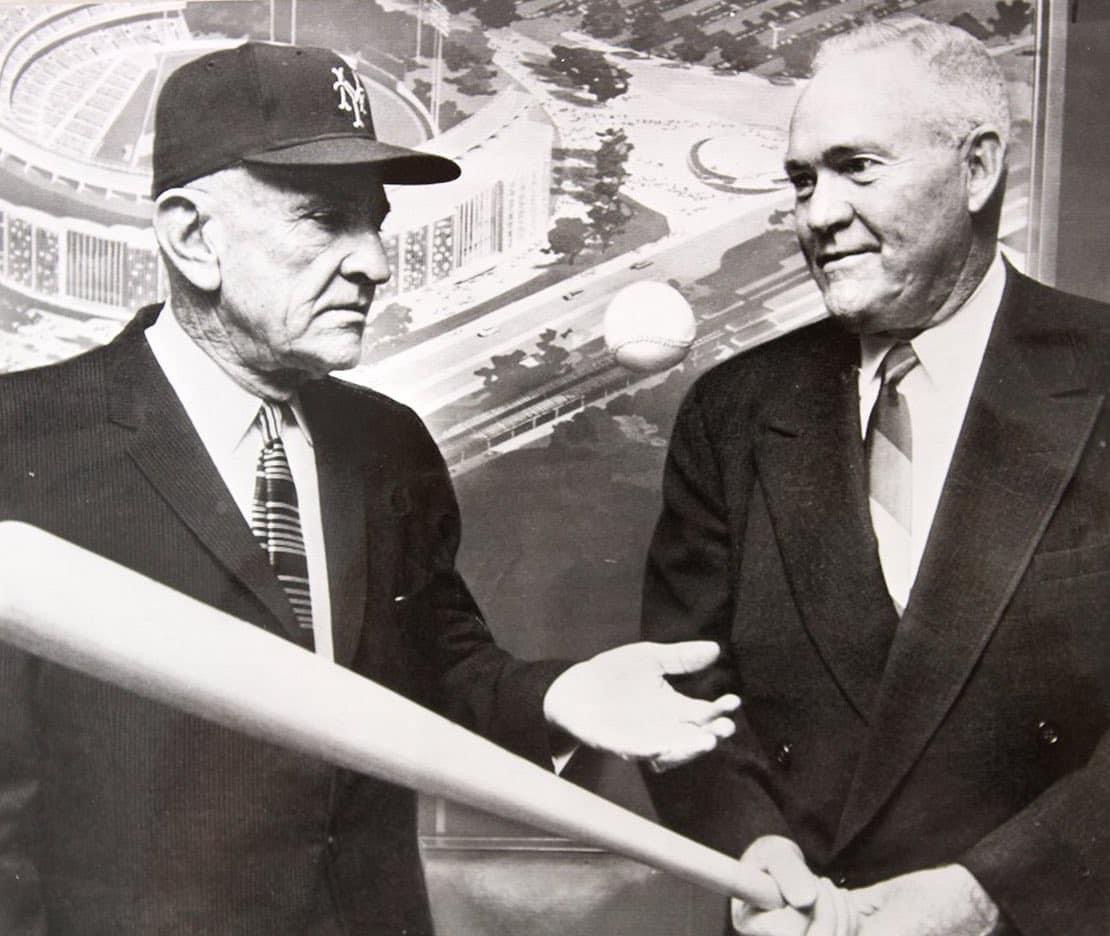

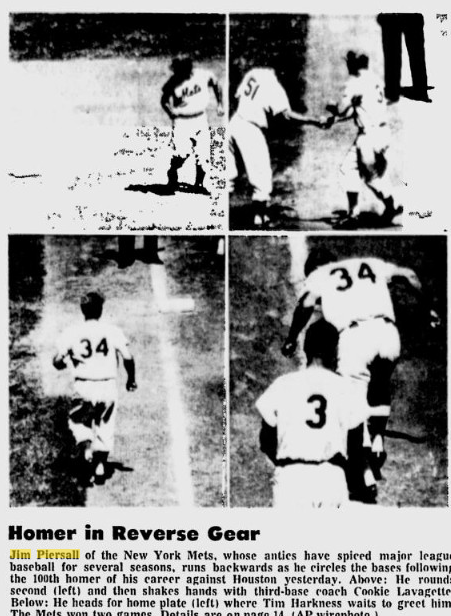

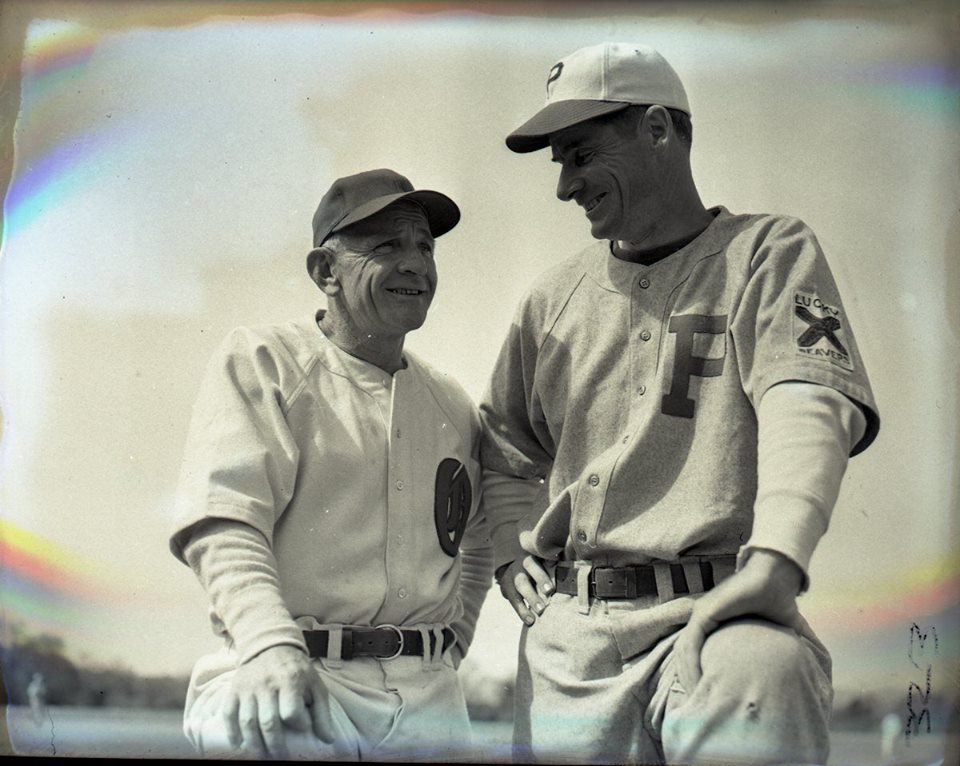

The Casey Stengel legend is well-known among baseball enthusiasts. A prime contender for the title of greatest manager ever, his greatest fame came from managing the Yankees to ten pennants and seven World Championships between 1949 and 1960. His quotes, delivered in a personal language dubbed “Stengelese,” are famous for their practicality, their humor, and their longwindedness. The Stengel story begins in late 1912 when the rookie, renamed for his hometown of Kansas City, went 4-for-4 in his first game ever to set a since-broken record. In 1913 he became the Dodgers’ regular centerfielder; in 1914 the team moved him over to right field. When Wilbert Robinson took over the team as their manager in 1915, Stengel’s education began. Stengel, through long practice, made himself an expert at the tricky caroms off the oddly angled concrete wall in Ebbets Field. He would later astonish the young Mickey Mantle by taking him out there to teach Mantle how to play the caroms before the 1952 World Series; Mantle couldn’t conceive of Stengel as having been a player 35 years earlier. Stengel played fairly regularly for Brooklyn, sometimes being platooned, until 1917. He was a line-drive hitter, a hard swinger who, unlike most players of the era, held the bat down at the end instead of choking up. In 1916 he got his first taste of postseason play and hit .364 in the World Series for Brooklyn. On January 9, 1918 he was traded along with infielder George Cutshaw to the Pittsburgh Pirates for infielder Chuck Ward, pitcher Burleigh Grimes, and pitcher Al Mamaux. He sat on the bench for Pittsburgh in 1918 and 1919. It was during 1919 that one of Stengel’s most famous antics took place. During the course of a rough Sunday afternoon in Brooklyn against his old teammates, Stengel had received a small bird from one of the Dodger pitchers in the bullpen and when he came up to bat, Stengel tipped his hat to the jeering crowd; out flew the bird, to the delight of the fans. This along with other antics caused Stengel to be traded to the Philadelphia Phillies in August for outfielder Possum Whitted. He played right field until, on July 1, 1921, he was traded to the New York Giants along with infielder Johnny Rawlings and pitcher Red Causey for outfielder Goldie Rapp, outfielder Lee King, and outfielder Lance Richbourg. He was ecstatic that he would be playing under the skilled hands of John McGraw, who would go on to teach him most about managing. He became a backup outfielder for the Giants and was on three pennant winners from 1921 to 1923. He sat on the bench in the 1921 WS but did well in 1922 in a limited role. In 1923 he hit two game-winning home runs. In Game One his inside-the-park homer with two out in the ninth inning gained added drama from his seemingly torturous course around the bases; sportswriters assumed it was due to age, but in fact one of his shoes was falling apart, making him limp. On November 12, 1923 the Giants shuffled him along with Dave Bancroft and Bill Cunningham to the Boston Braves for Bill Southworth and Joe Oeschger. He was the regular right fielder for the cellar-dwelling Braves in 1924, but by 1925 his playing days in the majors were over. In 1926 he was hired to manage the Toledo Mud Hens of the minor leagues, but he lost that job in 1931 when the team went bankrupt and into receivership. In December 1931 he was hired as a coach for the Brooklyn Dodgers and on February 23, 1923 he took over as the Dodger manager from the fired Max Carey. His greatest thrill of that first year was beating the Giants in the final series of the season and thus gaining revenge for a comment Giants manager Bill Terry had made earlier in the year (“Is Brooklyn still in the league?”). Casey struggled with the Dodgers for three years, with a sixth-place finish in 1934, a fifth-place finish in 1935, and a seventh-place finish in 1936. Years later, he mused, “Brooklyn, that borough of churches and bad ball clubs, many of which I had.” Stengel was fired by Brookyn at the end of the 1936 season and in 1938 was named manager of the Boston Braves, then called the Bees. He managed the team for six years from 1938 through 1943, never finishing higher than fifth place (in his first year there). He was let go in spring 1944 and went back to managing in the minor leagues. He took over the Milwaukee Brewers (American Association) in 1944 and led them to a first-place finish. Quitting there in 1945, he took over Kansas City of the American Association and led them to a seventh-place finish before he was pushed out of that job. Taking over Oakland (Pacific Coast League), whose GM was George Weiss, in 1946, Stengel led the Oaks to a second-place finish, a fourth-place finish (1947), and a first-place berth (1948). In 1949 the New York Yankees, whose GM was old friend Weiss, called on Casey to take over the managerial reins from Bucky Harris. At a press conference, Casey summed up his naivete with the comment, “This is a big job, fellows, and I barely have had time to study it. In fact, I scarcely know where I am at.” The baseball establishment, judging him by his previous failures with bad ballclubs, dismissed Stengel as a clown, but he shocked them with a World Championship; the Yankees had finished third the year before. Stengel went on to make it five consecutive World Championships, a record not only for World Championships, but even for pennants, breaking McGraw’s consecutive-pennants record set from 1921 to 1924, with Stengel on that team for the first three years. Stengel began to use an extensive platooning strategy that was soon emulated elsewhere, although never with the same complexity. He took the idea from the way Robinson and then McGraw had platooned Stengel himself years before. Stengel had inherited a team already considered a powerhouse that included the immortal Joe DiMaggio. Within three years he had remade it into a completely different type of ballclub. Rather than featuring superstars at most every position, Stengel built his team around just three: Mickey Mantle, Yogi Berra, and Whitey Ford. Mantle in particular was a special project of Stengel’s; the manager wanted his protege’s fame to exceed that of any other player and reflect credit on Stengel himself. The rest of the team consisted of role-players, many of whom would have preferred to be regulars; Stengel had them compete against each other for playing time, which drove them to perform at their highest level whenever they were in the game. Some players found it hard to take; Hank Bauer and Gene Woodling in particular chafed under their restricted playing time. Stengel once said, “The secret of managing is to keep the five guys who hate you away from the five who are undecided.” But some of his players worshiped him, in particular Billy Martin. Stengel treated the scrappy second baseman like a son, and later, when in Oakland for Stengel’s funeral, Martin slept in Stengel’s bed overnight. It has been said of Stengel that he never established a pitching rotation in his 12 seasons with the Yankees. He was protective of Ford to the point that Whitey didn’t get enough starts to win 20 games until 1961, when new manager Ralph Houk gave him the 39 starts that were normal for a staff ace; only in 1955 had Ford’s starts exceeded 30. The Big Four of Stengel’s best staff, Ford, Vic Raschi, Allie Reynolds, and Ed Lopat, were all used in relief. The Yankees finished in second place in 1954 despite their most wins under Stengel (103); Al Lopez’s Indians set the AL wins record that season with 111. Lopez was a catcher for Stengel in 1934 at Brooklyn. In 1955 the Yankees were back on top and continued winning AL pennants in 1956, 1957 and 1958. In 1958 he was involved in perhaps his most famous off-field incident. On July 9 he was called in front of the Senate Subcommittee on Antitrust and Monopoly to testify on why baseball should be exempt from antitrust regulation. He gave an hour’s worth of classic Stengelese to the baffled and amused politicians. After Stengel left the stand, Mantle was asked to testify. “My views are about the same as Casey’s,” he replied with a straight face. The Yankees finished third in 1959 to the White Sox, managed, like the 1954 Indians, by Al Lopez. In 1960 New York finished on top again, only to lose the World Series to the Pittsburgh Pirates and Bill Mazeroski. The Yankees fired Stengel a few days later for being too old. “I’ll never make the mistake of being seventy again,” Casey quipped. His friend Weiss was also fired. In the 12 years that Stengel had managed the Yankees, he set records, including the most years as a championship manager in the American League (10); the most consecutive first-place finishes (5); the most World Series games managed (63); and the most World Series wins (37). He won seven World Championships: 1949-53, 1956, and 1958. However, the Stengel story was not over. In 1962 he was named manager of the newly founded New York Mets, and George Weiss was named GM. Stengel said, “It’s great to be back in the Polar Grounds again with the New York Knickerbockers.” The 1962 Mets went on to become one of the worst teams in baseball history, finishing with a 40-120 record. Some 1962-vintage quotes: “Can’t anybody here play this game?” “Look at him. He can’t hit, he can’t run and he can’t throw. That’s why they gave him to us.” The Mets became quite popular despite, or perhaps because of, their ineptness, and Stengel skillfully distracted the press with his endless string of witticisms. Comedian George Gobel said of Stengel, “If he turned pro, he’d put us all out of business.” Stengel managed until mid-1965, when a broken hip forced him to retire a week before his 75th birthday. He spent his retirement working in a bank in Glendale, California with a sign on his desk that read, “Stengelese Spoken Here.” He died on September 29, 1975. His career was summed up perfectly by The Old Professor himself: “There comes a time in every man’s life and I’ve had plenty of them.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.