Eddie Collins Stats & Facts

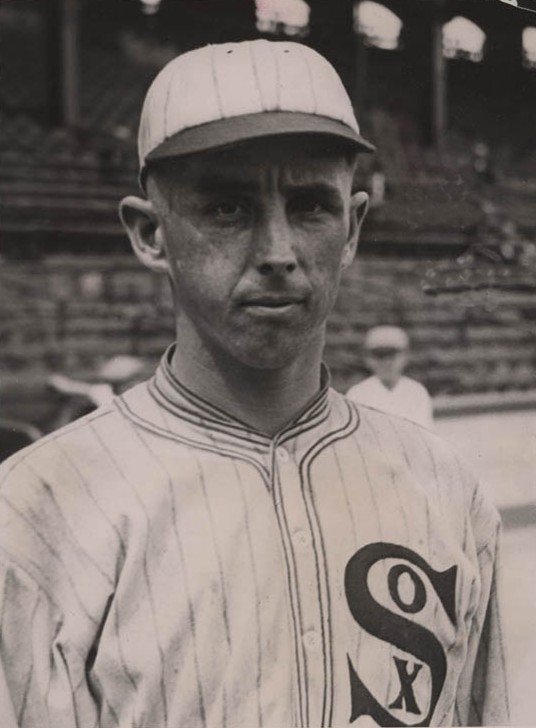

Eddie Collins

Position: Second Baseman

Bats: Left • Throws: Right

5-9, 175lb (175cm, 79kg)

Born: May 2, 1887 in Millerton, NY

Died: March 25, 1951 in Boston, MA

Buried: Linwood Cemetery, Weston, MA

High School: Washington Irving HS (Tarrytown, NY)

School: Columbia University (New York, NY)

Debut: September 17, 1906 (2,888th in MLB history)

vs. CHW 4 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 1 SB

Last Game: August 5, 1930

vs. BOS 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1939. (Voted by BBWAA on 213/274 ballots)

View Eddie Collins’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Edward Trowbridge Collins

Nicknames: Cocky

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Relatives: Father of Eddie Collins

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1906

Eddie Collins

Roy Hartzell

Red Murray

Johnny Bates

Oscar Stanage

Bill Carrigan

Babe Adams

Jack Coombs

Ed Willett

The Eddie Collins Teammate Team

C: Ray Schalk

1B: Stuffy McInnis

2B: Danny Murphy

3B: Frank Baker

SS: Jack Barry

LF: Joe Jackson

CF: Amos Strunk

RF: Harry Hooper

SP: Chief Bender

SP: Rube Waddell

SP: Eddie Cicotte

SP: Ted Lyons

RP: Lefty Grove

M: Connie Mack

Notable Events and Chronology for Eddie Collins Career

“I doubt if anyone will dispute my selection of Eddie Collins as the greatest second baseman of all time . . .” – John McGraw, writing in 1923

“He was the greatest second baseman I had ever seen. . .Plays which were difficult for even a finished infielder were made to seem easy.” – Bucky Harris, writing in 1925, quoted by Bill James

A member of four World Championship teams, Eddie Collins was a winner with a confident and aggressive style of play. He played 25 years in the major leagues and was considered the finest second baseman of his time. He led his league in fielding nine times, and he accepted more chances, had more assists, and made more putouts than any other pivot man in history. He was one of the best performers in World Series play, hitting .328 with 42 hits and 14 stolen bases in 34 games.

Full Bio

Edward Trowbridge Collins Jr. was a rarity in baseball’s early days – he attended college. The 19-year old joined the Philadelphia Athletics in 1906, fresh from the campus of Columbia University. Two years later he was the starting second baseman for Connie Mack’s A’s, helping to form the famed $100,000 Infield.

When Collins arrived for a short stay with the A’s in 1906, he played under the name “Sullivan” to protect his identity and eligibility for college sports. He was at the time the starting quarterback for the Columbia football team.

From 1910 to 1914, the A’s won four of five AL pennants, and three World Titles. They were a dynasty built around speed, defense, and pitching. Collins was a fantastic World Series performer for the A’s, hitting .429 in the 1910 Series with four steals, and .421 with three swipes in the 1913 Fall Classic.

Collins was a slap hitter with great bat control and patience. He led the AL in walks in 1915 with 119. He was usually used as a leadoff man, leading the league in runs from 1912-1914. Next to Ty Cobb he was the best base stealer of his era, leading the circuit in 1910 with 81 thefts. He also led in steals in 1923 and 1924, when he was past the age of 36. While baseball moved away from inside baseball tactics in the 1920s, Collins remained steadfast.

After the 1914 season, Collins was sold to the Chicago White Sox for $50,000. He starred for the Sox for the next twelve seasons, playing more games in their uniform than he had for Philadelphia. In 1916 he enjoyed a 20-game batting streak. He was named captain of the team by manager Kid Gleason. In 1917 the Sox won the World Series and in 1919 they lost it to the Reds. The 1919 Series was crooked – with eight players playing dishonestly. Collins set a record in that Fall Classic with his 14th steal in the post-season.

He was named player/manager of the Sox late in 1924, and the next two seasons he guided them to winning records. He was released by Chicago following the 1926 season and re-joined Mack on the A’s. With the A’s he was a coach and player, mostly a pinch-hitter. In 1927 he led the AL with 12 pinch-hits, in 34 at-bats. He joined Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker on the 1928 A’s team and last appeared as a player in 1930. In 1929, after the death of Miller Huggins, Collins was offered the job of managing the Yankees. He refused, believing he would follow Mack as skipper of the A’s. Except, Mack did not retire until he was 88, 23 years later.

Instead, Collins’s opportunity to run a team came with the Boston Red Sox. He and Tom Yawkey were alumni of the same prep school and became friends. The millionaire sportsman, on Collins’s advice, purchased the Red Sox and brought Collins in as part-owner and GM. Collins began rebuilding a team that had never recovered from the sale of stars to the Yankees a decade earlier. Yawkey’s money bought Joe Cronin from Washington to be player-manager, and pried loose stars Jimmie Foxx and Lefty Grove from the A’s. Collins went on just one scouting trip for the Red Sox, to California, but came back with two extraordinary prospects, Bobby Doerr and Ted Williams.

Eddie Collins was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1939, the year Eddie, Jr. debuted with the Athletics as an outfielder. Collins holds the AL record for service, at 25 seasons. He holds the White Sox single-season mark with his 224 hits in 1920, a season in which he had a 22-game hitting streak. Twice he stole six bases in one game, within a two-week stretch in 1912. His career steals total ranks among the top-ten on the all-time list.

World Series Hero

Eddie Collins was an unlikely superstar. He was just 5-foot-9 and 170 pounds, a collegiate player who often was razzed by opposing players. The insults often concerned his college background, small stature, and big ears. But where Collins was big-eared, he was also hard-nosed. By 1909 he was one of the best second baseman in baseball, challenging Nap Lajoie for laurels. He batted .347 in 1909, the first of eight straight seasons he topped .300 as a regular. In the 1920s he reached .300 nine more times.

The Philadelphia A’s of that time were stocked with great players. Chief Bender, Eddie Plank, and Jack Coombs led the mound corps. Frank “Home Run” Baker, Harry Davis, Jack Barry, Stuffy McInnis, and Wally Schang were offensive and defensive standouts. The team was led by Connie Mack, who not only managed the team, but owned it as well. Mack would be at the Athletics helm for 50 years. In 1910, 1911, 1913, and 1914 the A’s won the AL pennant, never by less than 6 ½ games. They were a dynasty. Collins was an integral part of that team, leading them in the regular season, but also in the World Series – where he flourished.

In the 1910 World Series the A’s met the Cubs, a team strong in pitching. Collins ignored that fact and batted .429 (9-for 21), leading all hitters. He set a Series record with four doubles and four steals. He also drove in three runs and scored five times. The A’s won in five games. During that Series Collins toyed with Cubs catcher Johnny Kling. On one occasion he stayed put at first base while Kling called for three straight pitchouts. On the fourth pitch – a strike – Collins swiped second easily.

1917 World SeriesThe next fall, Collins collected six hits (.286) in a six-game World Series win over the New York Giants. The speedy infielder stoled two bases as well. In 1913 he had perhaps his finest Series, batting .421 (8-for-19) with five runs scored and three RBI. In Game Three his three hits led the A’s to an 8-2 victory. He also scored three more bases, and two of his eight safeties were triples. The Athletics were World Champs again – their third title in four seasons.

In 1914 Philadelphia entered the Fall Classic as huge favorites against the Boston Braves – who had won the NL pennant with a dramatic second-half run. But two no-name Boston hurlers (Dick Rudolph and Bill James) handcuffed the A’s, winning two games each. In the shocking four-game loss, Collins batted just .214 (3-for-14) and stoled one base. His ten career World Series steals to that point, were a record.

In 1914, Collins won the Chalmers Award – given to the Most Valuable Player in the American League. He hit .344 and led the league in runs and on-base percentage. But after the season, Mack was forced to sell off most of his stars, due to financial hardship. “The $100,000 Infield” was broken up and Collins was shipped to the White Sox. Chicago acquired Joe Jackson during the 1915 season, and teamed him with Collins for a feared offensive tandem.

By 1917 the Sox were the best team in the AL, winning 100 games in a war-shortened season. In the World Series, Collins was right at home, facing John McGraw and the Giants, who the A’s had defeated twice during his years there. In the 1917 Series Collins tormented his old nemesis, batting .409 (9-for-22) with four runs scored and three swipes. In Game Six at the Polo Grounds, with Chicago leading three games to two and needing just one more victory, Collins was part of one of the strangest plays in World Series history. After three innings, Red Faber and Rube Benton were knotted in a scoreless duel. Collins reached second on an error by third baseman Heinie Zimmerman. Joe Jackson lofted a flyball to right field that Dave Robertson muffed, allowing Collins to move to third. Happy Felsch followed with a slow roller to Benton on the mound and Collins was off for the plate. Benton fielded the ball and fired to Zimmerman, who chased Collins toward catcher Bill Rariden. But rather than throw to Rariden for the easy putout, Zimmerman tried to make the play himself, and Collins sped past the shocked catcher to score. Before the inning was over Chicago had scored three times and was on the way to their first World Series title. It was the fourth for Collins.

The 1919 World Series has been well documented both in print and film, due to the infamous Black Sox scandal in which eight players for the White Sox (including Joe Jackson) played dishonestly. Collins and the other honest Sox could only watch in disbelief as teammates lobbed pitches, muffed balls, and struck out mysteriously. Collins, playing in his sixth and final Fall Classic, went 7-for-31 (.226) with a double, RBI, and one stolen base. His stolen base gave him a total of 14, a World Series record that Lou Brock later matched.

Eddie Collins was one of the first World Series heroes of baseball. He played a vital role on four World Series winners, beating the Giants three times and the Cubs once. Both of his World Series losses were huge upsets – one due to a fix and the other a shocking sweep at the hands of the “Miracle Braves.” In 34 World Series games, Collins batted .328 (42-for-128), with 20 runs scored and 11 RBI. He had seven doubles and two triples to go along with his 14 steals. His 20 runs scored in World Series play are the most for any player who didn’t wear a Yankee uniform. His 53 total bases are the second highest for a player who never hit a World Series home run (Frankie Frisch had 74 total bases). Eddie Collins was a winner.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Philadelphia Athletics (1906-1914)

Chicago White Sox (1915-1926)

Philadelphia Athletics (1927-1930)

Managed

Chicago White Sox (1924-1926)

Similar: None. Imagine Roberto Alomar hitting like Tony Gwynn and stealing bases like Tim Raines.

Linked: Home Run Baker, Stuffy McInnis, Danny Murphy, Jack Barry… Bobby Doerr, Ted Williams, who were both scouted and signed by Collins when he was working for the Red Sox in the 1930s.

Awards and Honors

1914 AL MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1910 World Series

1911 World Series

1913 World Series

1914 World Series

1917 World Series

1919 World Series

Factoid

Eddie Collins buried his bats during the off-season in shallow holes in his backyard that he called “graves” in order to keep them “lively.”

Full Bio

Edward Trowbridge Collins Jr. was a rarity in baseball’s early days – he attended college. The 19-year old joined the Philadelphia Athletics in 1906, fresh from the campus of Columbia University. Two years later he was the starting second baseman for Connie Mack’s A’s, helping to form the famed $100,000 Infield.

When Collins arrived for a short stay with the A’s in 1906, he played under the name “Sullivan” to protect his identity and eligibility for college sports. He was at the time the starting quarterback for the Columbia football team.

From 1910 to 1914, the A’s won four of five AL pennants, and three World Titles. They were a dynasty built around speed, defense, and pitching. Collins was a fantastic World Series performer for the A’s, hitting .429 in the 1910 Series with four steals, and .421 with three swipes in the 1913 Fall Classic.

Collins was a slap hitter with great bat control and patience. He led the AL in walks in 1915 with 119. He was usually used as a leadoff man, leading the league in runs from 1912-1914. Next to Ty Cobb he was the best base stealer of his era, leading the circuit in 1910 with 81 thefts. He also led in steals in 1923 and 1924, when he was past the age of 36. While baseball moved away from inside baseball tactics in the 1920s, Collins remained steadfast.

After the 1914 season, Collins was sold to the Chicago White Sox for $50,000. He starred for the Sox for the next twelve seasons, playing more games in their uniform than he had for Philadelphia. In 1916 he enjoyed a 20-game batting streak. He was named captain of the team by manager Kid Gleason. In 1917 the Sox won the World Series and in 1919 they lost it to the Reds. The 1919 Series was crooked – with eight players playing dishonestly. Collins set a record in that Fall Classic with his 14th steal in the post-season.

He was named player/manager of the Sox late in 1924, and the next two seasons he guided them to winning records. He was released by Chicago following the 1926 season and re-joined Mack on the A’s. With the A’s he was a coach and player, mostly a pinch-hitter. In 1927 he led the AL with 12 pinch-hits, in 34 at-bats. He joined Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker on the 1928 A’s team and last appeared as a player in 1930. In 1929, after the death of Miller Huggins, Collins was offered the job of managing the Yankees. He refused, believing he would follow Mack as skipper of the A’s.

Collins holds the AL record for service, at 25 seasons. He holds the White Sox single-season mark with his 224 hits in 1920, a season in which he had a 22-game hitting streak. Twice he stole six bases in one game, within a two-week stretch in 1912. His career steals total ranks among the top-ten on the all-time list. He followed his playing and coaching career as general manager of the Boston Red Sox until 1951. With the BoSox he helped rebuild the team, and was instrumental in the signings of Bobby Doerr and Ted Williams.

Feats: Twice in his career, Collins stole six bases in one game… On September 22, 1912, he stole second, third, and home in the same inning.

Milestones

On June 3, 1925, Collins stroked his 3,000th career hit.

Hitting Streaks

22 games (1920)

22 games (1920)

20 games (1916)

20 games (1916)

Transactions

December 8, 1914: Purchased by the Chicago White Sox from the Philadelphia Athletics.

This might have been the best transaction in the history of the Chicago White Sox. In Collins’s third season with the team, they won the World Series. In his fifth season they had the best record in baseball and lost the World Series only because of eight dishonest players.

World Series Hero

Eddie Collins was an unlikely superstar. He was just 5-foot-9 and 170 pounds, a collegiate player who often was razzed by opposing players. The insults often concerned his college background, small stature, and big ears. But where Collins was big-eared, he was also hard-nosed. By 1909 he was one of the best second baseman in baseball, challenging Nap Lajoie for laurels. He batted .347 in 1909, the first of eight straight seasons he topped .300 as a regular. In the 1920s he reached .300 nine more times.

The Philadelphia A’s of that time were stocked with great players. Chief Bender, Eddie Plank, and Jack Coombs led the mound corps. Frank “Home Run” Baker, Harry Davis, Jack Barry, Stuffy McInnis, and Wally Schang were offensive and defensive standouts. The team was led by Connie Mack, who not only managed the team, but owned it as well. Mack would be at the Athletics helm for 50 years. In 1910, 1911, 1913, and 1914 the A’s won the AL pennant, never by less than 6 ½ games. They were a dynasty. Collins was an integral part of that team, leading them in the regular season, but also in the World Series – where he flourished.

In the 1910 World Series the A’s met the Cubs, a team strong in pitching. Collins ignored that fact and batted .429 (9-for 21), leading all hitters. He set a Series record with four doubles and four steals. He also drove in three runs and scored five times. The A’s won in five games. During that Series Collins toyed with Cubs catcher Johnny Kling. On one occasion he stayed put at first base while Kling called for three straight pitchouts. On the fourth pitch – a strike – Collins swiped second easily.

The next fall, Collins collected six hits (.286) in a six-game World Series win over the New York Giants. The speedy infielder stoled two bases as well. In 1913 he had perhaps his finest Series, batting .421 (8-for-19) with five runs scored and three RBI. In Game Three his three hits led the A’s to an 8-2 victory. He also scored three more bases, and two of his eight safeties were triples. The Athletics were World Champs again – their third title in four seasons.

In 1914 Philadelphia entered the Fall Classic as huge favorites against the Boston Braves – who had won the NL pennant with a dramatic second-half run. But two no-name Boston hurlers (Dick Rudolph and Bill James) handcuffed the A’s, winning two games each. In the shocking four-game loss, Collins batted just .214 (3-for-14) and stoled one base. His ten career World Series steals to that point, were a record.

In 1914, Collins won the Chalmers Award – given to the Most Valuable Player in the American League. He hit .344 and led the league in runs and on-base percentage. But after the season, Mack was forced to sell off most of his stars, due to financial hardship. “The $100,000 Infield” was broken up and Collins was shipped to the White Sox. Chicago acquired Joe Jackson during the 1915 season, and teamed him with Collins for a feared offensive tandem.

By 1917 the Sox were the best team in the AL, winning 100 games in a war-shortened season. In the World Series, Collins was right at home, facing John McGraw and the Giants, who the A’s had defeated twice during his years there. In the 1917 Series Collins tormented his old nemesis, batting .409 (9-for-22) with four runs scored and three swipes. In Game Six at the Polo Grounds, with Chicago leading three games to two and needing just one more victory, Collins was part of one of the strangest plays in World Series history. After three innings, Red Faber and Rube Benton were knotted in a scoreless duel. Collins reached second on an error by third baseman Heinie Zimmerman. Joe Jackson lofted a flyball to right field that Dave Robertson muffed, allowing Collins to move to third. Happy Felsch followed with a slow roller to Benton on the mound and Collins was off for the plate. Benton fielded the ball and fired to Zimmerman, who chased Collins toward catcher Bill Rariden. But rather than throw to Rariden for the easy putout, Zimmerman tried to make the play himself, and Collins sped past the shocked catcher to score. Before the inning was over Chicago had scored three times and was on the way to their first World Series title. It was the fourth for Collins.

The 1919 World Series has been well documented both in print and film, due to the infamous Black Sox scandal in which eight players for the White Sox (including Joe Jackson) played dishonestly. Collins and the other honest Sox could only watch in disbelief as teammates lobbed pitches, muffed balls, and struck out mysteriously. Collins, playing in his sixth and final Fall Classic, went 7-for-31 (.226) with a double, RBI, and one stolen base. His stolen base gave him a total of 14, a World Series record that Lou Brock later matched.

Eddie Collins was one of the first World Series heroes of baseball. He played a vital role on four World Series winners, beating the Giants three times and the Cubs once. Both of his World Series losses were huge upsets – one due to a fix and the other a shocking sweep at the hands of the “Miracle Braves.” In 34 World Series games, Collins batted .328 (42-for-128), with 20 runs scored and 11 RBI. He had seven doubles and two triples to go along with his 14 steals. His 20 runs scored in World Series play are the most for any player who didn’t wear a Yankee uniform. His 53 total bases are the second highest for a player who never hit a World Series home run (Frankie Frisch had 74 total bases). Eddie Collins was a winner.

Factoid

In 2005, Eddie Collins was inducted into the Columbia University Athletics Hall of Fame. Collins played baseball for Columbia in 1907. Other inductees included Lou Gehrig.

Replaced

Philadelphia’s own Danny Murphy was the second baseman for Connie Mack in the early 1900s, replaced by Collins in 1908. Murphy moved to right field, where he played well for the Athletics for several more years.

Replaced By

As player/manager of the White Sox in 1926, Collins was grooming his successor: Ray Morehart. But when Collins was set adrift after the ’26 season, the White Sox traded Morehart to the Yankees in a deal that netted them veteran second baseman Aaron Ward. Ward played one season in Chicago, hitting .270 in 145 games in 1927.

Best Strength as a Player

Speed and baseball instincts.

Largest Weakness as a Player

Power

Other Resources & Links