Gil Hodges Stats & Facts

VINTAGE BASEBALL MEMORABILIA

Vintage Baseball Memorabilia

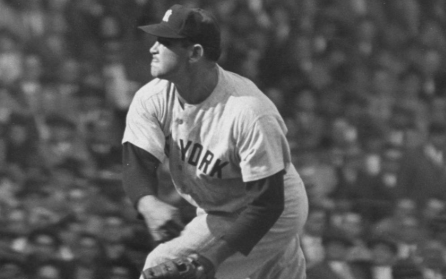

Gil Hodges

Positions: First Baseman and Outfielder

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-1, 200lb (185cm, 90kg)

Born: April 4, 1924 in Princeton, IN

Died: April 2, 1972 in West Palm Beach, FL

Buried: Holy Cross Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY

High School: Petersburg HS (Petersburg, IN)

School: St. Joseph’s College (Rensselaer, IN)

Debut: October 3, 1943 (9,562nd in major league history)

vs. CIN 2 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 1 SB

Last Game: May 5, 1963

vs. SFG 4 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Full Name: Gilbert Raymond Hodges

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1943

Gil Hodges

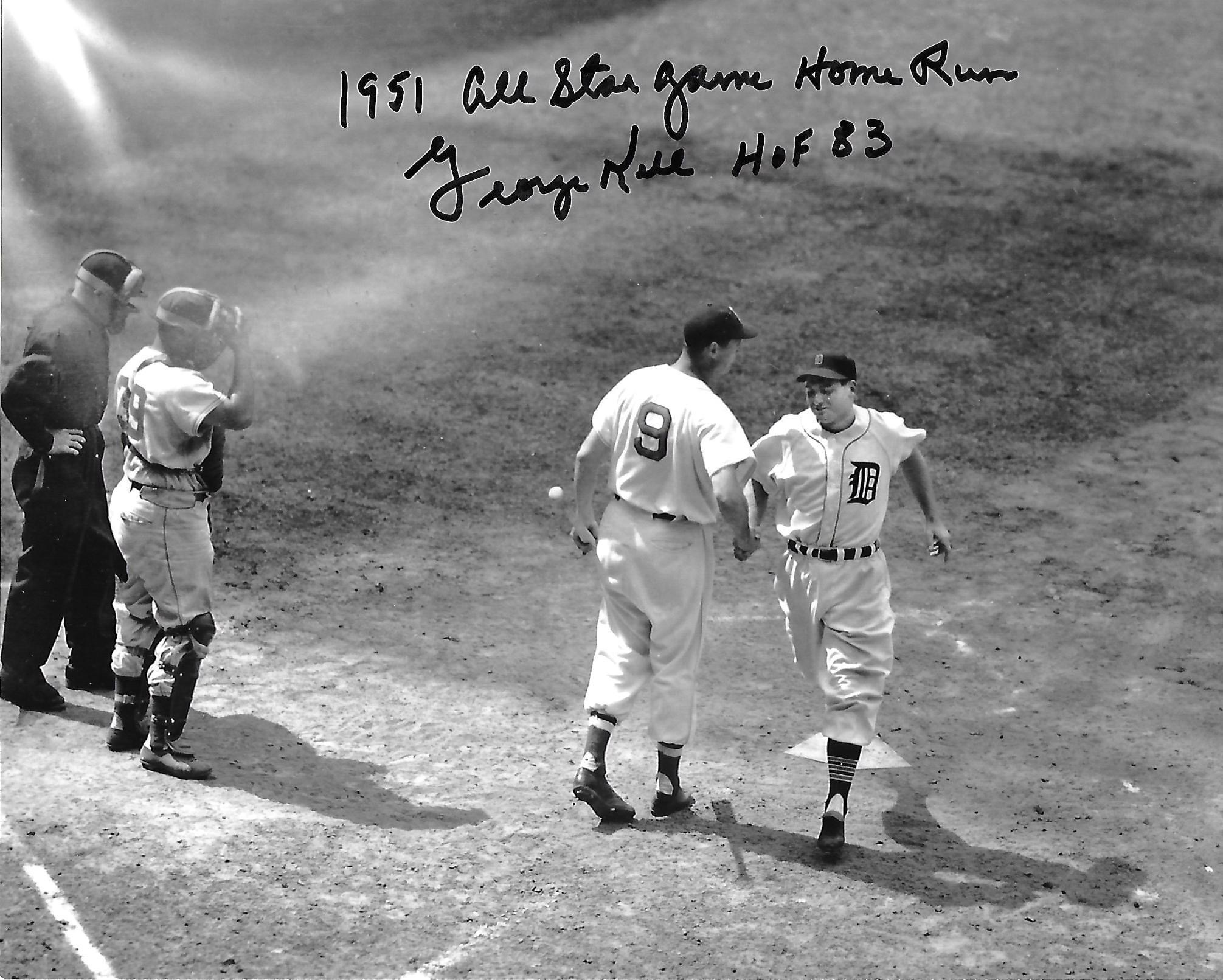

George Kell

Andy Pafko

Gene Woodling

Andy Seminick

Cass Michaels

Eddie Stanky

Snuffy Stirnweiss

Mickey Haefner

Notable Events and Chronology for Gil Hodges Career

Biography

Gil Hodges Biography

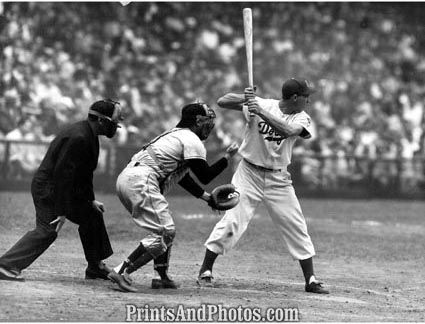

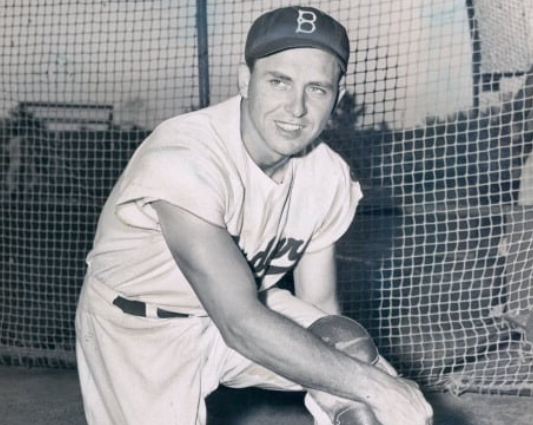

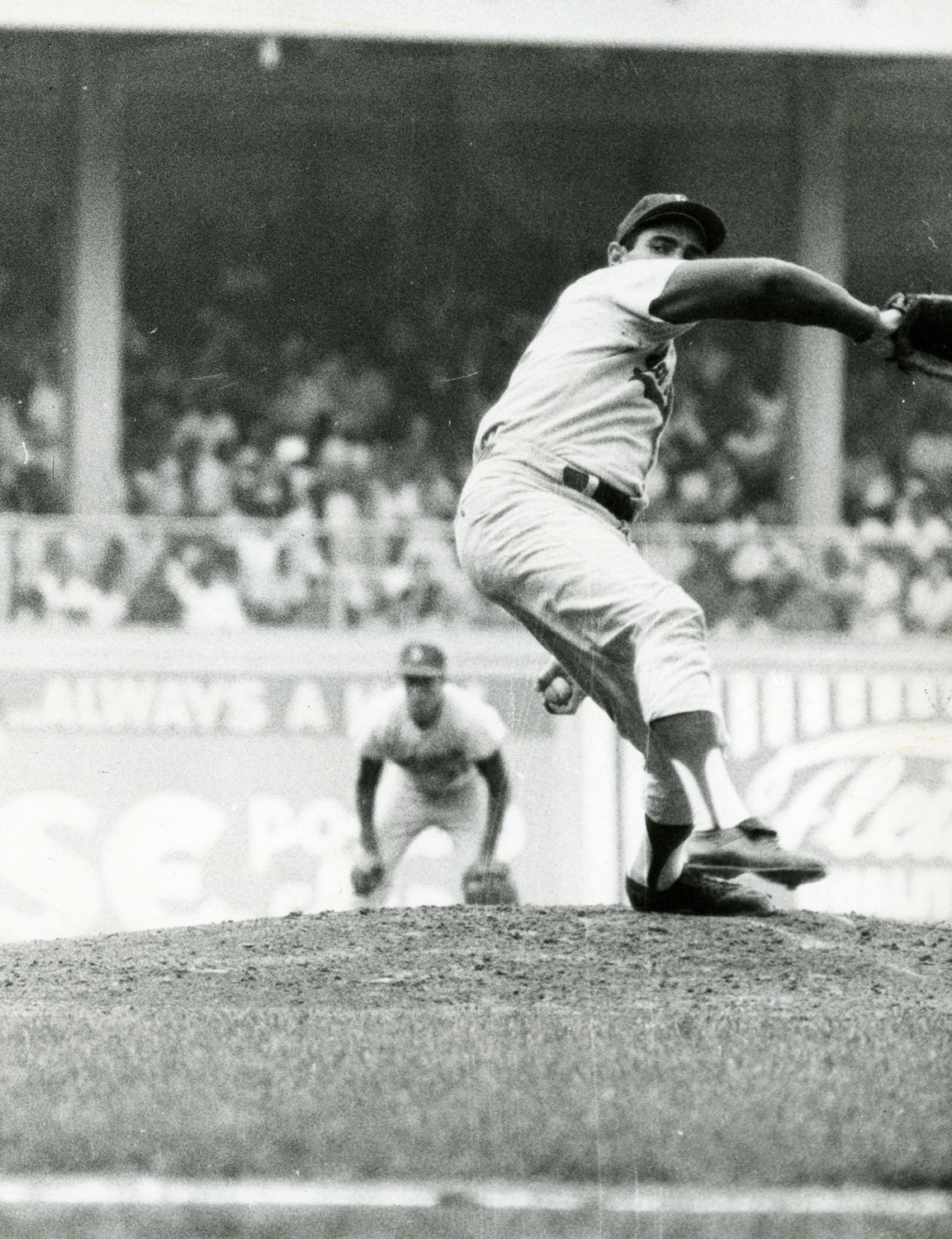

Perhaps the most beloved player on a Brooklyn Dodgers team that dominated the National League from 1949 to 1956, Gil Hodges made key contributions to six pennant-winning teams and two world championship clubs during his 15 years with the Dodgers. A power-hitting first baseman who excelled in the field as well, Hodges gained general recognition as the senior circuit’s finest all-around player at his position for much of the 1950s. No other player drove in more runs during the decade than the 1,001 Hodges knocked in for the Dodgers, and only teammate Duke Snider hit more homers than the 310 Hodges drove out of the ballpark during that 10-year period. The powerful first baseman also provided leadership to his Dodger teammates both on and off the field with his calm demeanor, quiet strength, and strong sense of decency.

Biography:

Born in Princeton, Indiana on April 4, 1924, Gilbert Raymond Hodges spent most of his youth in nearby Petersburg after moving there with his family at the age of seven. A four-sport star at Petersburg High School, where he earned a combined seven varsity letters in baseball, football, basketball, and track, Hodges declined a 1941 contract offer he received from the Detroit Tigers shortly after he graduated. Instead, he elected to attend Saint Joseph’s College in the hope that he might eventually become a collegiate coach. Hodges spent two years at Saint Joseph’s before signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1943. He made his major-league debut with the team in early October, appearing in just one game at third base before entering the Marine Corps to take part in the war effort. Hodges spent the next 2 ½ years in the military, serving as an anti-aircraft gunner in the battles of Tinian and Okinawa, and receiving a Bronze Star and a commendation for courage under fire for his actions.

Hodges returned to Brooklyn after being discharged from the military in 1946 and appeared in 24 games behind the plate the following year for the pennant-winning Dodgers. With the arrival of Roy Campanella in 1948, manager Leo Durocher shifted Hodges to first base – a position he manned the remainder of his career. Hodges had a decent rookie year, hitting 11 home runs, driving in 70 runs, and batting .249.

The Dodger first baseman began to establish himself as one of the National League’s top sluggers in 1949, hitting 23 home runs, knocking in 115 runs, scoring 94 others, and batting .285. He also displayed his fielding prowess, leading all league first basemen in putouts, double plays, and fielding average, while placing second among players at his position in assists. Hodges’ fine all-around season helped the Dodgers capture the National League pennant, earning him an 11th place finish in the league MVP voting and the first of seven consecutive selections to the All-Star Team.

Although Brooklyn failed to return to the World Series in either of the next two seasons, finishing an extremely close second in the N. L. standings both years, Hodges continued his outstanding play. He combined to hit 72 home runs, drive in 216 runs, and score 216 others in 1950 and 1951, placing among the league leaders in home runs, runs batted in, and total bases both years. Hodges had the greatest day of his career on August 31, 1950 against the Boston Braves when he became just the second player since 1900 to hit four home runs in a game without the benefit of extra innings (Lou Gehrig was the first). The Dodger first baseman homered against four different pitchers, also singling in another at-bat to accumulate 17 total bases on the day. Hodges became the first Dodger player to hit 40 home runs the following season. He also scored a career-high 118 runs.

The Dodgers captured the National League pennant in both 1952 and 1953, with Hodges making key contributions to both winning efforts. He placed among the N.L. leaders in home runs and runs batted in both years, combining for 63 homers and 224 RBIs. Hodges also led all league first basemen in assists for the second of three times in 1952, before batting .302 and scoring 101 runs the following year.

The Yankees defeated the Dodgers in the World Series in both 1952 and 1953, squelching for the third and fourth times since 1947 Brooklyn’s hopes of winning a world championship. Hodges struggled terribly at the plate during the 1952 Fall Classic, failing to get a hit in 21 official at-bats. Yet, the first baseman’s ineffectiveness enabled him to realize just how much he meant to the fans of Brooklyn.

Brooklyn fans were a rowdy bunch that didn’t hesitate in the least to express their feelings – good or bad – to their beloved Dodgers. Sooner or later, every member of the team incurred their wrath; that is, everyone except Hodges. Immersed in the worst hitting slump of his young career, Hodges drew nothing but words of encouragement from the Dodger faithful, who sent him thousands of letters as a way of reaffirming their affection for him. Even the church showed its support for Hodges when his slump continued into the following spring. Father Herbert Redmond of St. Francis Roman Catholic Church in Brooklyn told his flock one day: “It’s far too hot for a homily. Keep the Commandments and say a prayer for Gil Hodges.” The Dodger first baseman began hitting again shortly thereafter, and he rarely struggled again in the World Series.

Hodges’ Dodger teammates similarly looked up to their powerful first baseman, expressing to a man their respect and admiration for him. Pitcher Carl Erskine said, “Gil was a quiet and private person, but everybody looked up to him because of his dedication and his strength and character. He never showed emotion. Never saw it on the outside. If a pitcher was in a tough situation, Gil would come over and say a few words, and it really made you calm down and concentrate. He had a real knack for that.”

Fellow Dodger hurler Clem Labine suggested, “Not getting booed at Ebbets Field was an amazing thing. Those fans knew their baseball, and Gil was the only player I can remember whom the fans never, I mean never booed.”

Hall of Fame catcher Roy Campanella said of Hodges, “He was never booed anyplace. They knew what kind of man he was, so they never booed him. He was a leader of our team. Everybody respected Gil and looked up to him. Gil, of course, went on to become the best first baseman in the league. In fact, he was the best first baseman I ever saw. He was just a great human being whom everybody respected. Everybody liked Gil Hodges.”

Dodger captain Pee Wee Reese stated, “If you had a son, it would be a great thing to have him grow up to be just like Gil Hodges.”

Meanwhile, Rachel Robinson wrote in her book about her deceased husband, Jackie Robinson: An Intimate Portrait, “In his own quiet way, Gil was a mainstay of the team; a slugger, an outstanding fielder, a man of strong character. Jack counted on him.”

Although the Dodgers failed to return to the World Series in 1954, Hodges had his finest statistical season, scoring 106 runs and establishing career highs with 42 home runs, 130 runs batted in, 176 hits, a .304 batting average, and a.579 slugging percentage. Appearing in all 154 games for the Dodgers, Hodges also led all National League first basemen in both putouts and assists, earning a 10th place finish in the league MVP voting in the process.

Hodges had a somewhat less productive season in 1955, hitting 27 home runs, driving in 102 runs, scoring 75 others, and batting .289. But the Dodgers finally reached their ultimate goal of winning a world championship by defeating the Yankees in the World Series in seven games. Hodges contributed to the Dodger cause by hitting one homer, driving in five runs, and batting .292 during the Fall Classic.

The Dodgers won their last pennant in Brooklyn the following year, before losing the World Series to the Yankees in seven games. Hodges had another solid year, hitting 32 homers and knocking in 87 runs. The 33-year-old first baseman had his last big year in 1957, a season in which the Milwaukee Braves replaced the Dodgers atop the National League standings. Hodges hit 27 home runs, drove in 98 runs, scored 94 others, and batted .299, en route to earning a seventh-place finish in the league MVP voting and the last of his eight All-Star nominations. He also won the first of three consecutive Gold Gloves for his outstanding defensive work at first base, in the first year Major League Baseball presented the annual awards.

The aging Hodges experienced a decrease in offensive production after the Dodgers moved to Los Angeles in 1958. He assumed a part-time role for the team the following year, hitting 25 homers and driving in 80 runs despite playing in only 124 games for the eventual world champions. Hodges saw his playing time continue to diminish over the course of the next two seasons, relegating him to back-up status.

Left unprotected by the Dodgers in the 1962 expansion draft, Hodges returned to New York later that year as an original member of the New York Mets. Plagued by knee problems throughout the campaign, Hodges appeared in only 54 games for the Mets. However, he hit the first home run in franchise history, finishing the year with a career total of 370 homers – the second most in baseball history by a right-handed batter at the time (behind only Jimmie Foxx).

After appearing in just nine games for the Mets through late May of the following season, Hodges announced his retirement when the team traded him to the Washington Senators. Assuming the Washington managerial position immediately upon his arrival, Hodges piloted the lowly Senators through 1967, helping the team improve its record each year.

Hodges was brought back to manage the equally woeful Mets prior to the start of the 1968 campaign. Although the Mets finished ninth in the National League in their first year under Hodges, their record of 73-89 represented the best mark in their seven-year existence. Hodges displayed his tremendous leadership skills the following year when he led a young and relatively inexperienced New York squad to the world championship. After winning 100 games during the regular season, the “Miracle Mets” swept Hank Aaron, Orlando Cepeda, Rico Carty and the rest of the Atlanta Braves in the NLCS, before stunning the heavily-favored Baltimore Orioles in five games in the World Series.

Hodges’ expert manipulation of his pitching staff and clever utilization of the somewhat limited talent available to him on an everyday basis earned him Manager of the Year honors from The Sporting News. Yet, equally important to the success of his team was the manner in which Hodges dealt with the psyche of his players. His handling of star leftfielder Cleon Jones provided clear and unequivocal evidence of that last fact.

After being embarrassed by the Houston Astros in the first game of a July 30 doubleheader, the Mets found themselves in the midst of another drubbing in the second contest. Houston scored 10 runs in the third inning of the nightcap, lining a number of base hits to left field in the process. When Jones failed to hustle after a ball hit into his territory, Hodges elected to remove the National League’s batting leader from the game. However, rather than simply signaling from the dugout for Jones to come out, or delegating the job to one of his coaches, Hodges left the dugout and walked slowly and deliberately all the way out to left field to remove Jones himself. He then walked the leftfielder back to the dugout, leaving a resounding message to the rest of the team. Jones never again failed to hustle under Hodges, whose quiet but disciplined character left a lasting impression on his players.

Third baseman Ed Charles, whose veteran presence on the 1969 Mets proved to be invaluable to the success of the team, later discussed the manner in which he looked up to Hodges, both as a manager and as a man: “I think one of his greatest assets was his ability to motivate players. Gil is one of the all-time greats at getting the best out of his players. I think one of the greatest impressions he made on me was when he started the platoon system in New York in 1968. He stuck to his plans, not the media’s plans, not the players’ plans, but his. And pretty soon we started winning. Gil was a fair man. Everybody on the team was equal. No exceptions. But he handled each player differently depending on his personality. He was a master at it. He could read people and he knew what made them tick. The players had total confidence in him. The lessons he taught his players went beyond the baseball field. He taught them lessons in life; How to conduct yourself as a gentleman, as a big leaguer; How to be a better person. There were just so many things Gil taught all of us.”

Don Cardwell, the elder statesman of New York’s pitching staff in 1969, also expressed his admiration for Hodges: “I always had great respect for Gil even when I was playing against him, and then later I played for him. He was head and shoulders above any other manager I ever played for. He was always looking ahead two or three innings; he knew what was coming up. I never played for another manager who was so into the game, who thought that far ahead. He was a father figure to all the younger guys on the club.”

Meanwhile, Cleon Jones discussed the lessons he learned playing under Hodges: “Gil Hodges was the best manager I ever played for. He had the ability to read into an individual and get out what he didn’t know he had. Normally, players make the manager; in this case the manager made the players. There were times when I really didn’t understand why Gil did the things he did. But now I look back and I realize what Gil was trying to teach us, not only as ballplayers, but as people. I think everybody who played for Gil will carry the lessons he taught them through their lives. If he had lived, he probably would have been the greatest manager who ever lived.”

Unfortunately, Gil Hodges did not live far beyond the 1969 season. After leading the Mets to identical 83-79 third-place finishes in 1970 and 1971, Hodges died suddenly of a heart attack on April 2, 1972, after playing golf earlier in the day with other members of New York’s coaching staff in West Palm Beach, Florida. Although he had previously suffered a heart attack during a game in September 1968, his passing stunned everyone close to him since it came two days shy of just his 48th birthday.

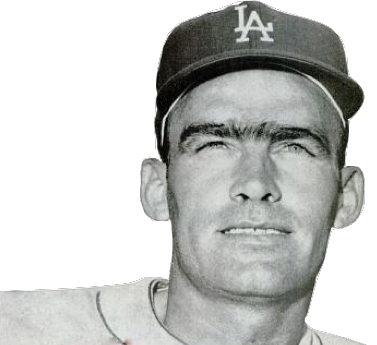

Numerous campaigns have since been waged to get Hodges elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. His supporters point to his 370 career home runs, 1,274 runs batted in, eight All-Star selections, and sterling defensive record. In fact, the most overlooked aspect of Hodges’ all-around game may well have been his fielding ability. Former teammate Carl Erskine called Hodges “…the best at first I ever saw; Great footing and range; Good hands; Made difficult plays look easy.”

Longtime Dodger right-fielder Carl Furillo stated, “Gil made everything look easy at first base. He was so smooth that even the hard plays looked easy when Gil made them. In all my years in baseball, I never saw a better first baseman than Gil.”

Hall of Fame centerfielder Duke Snider said, “We used to marvel at the way Gil could play defense. Any throw that went over to first base you knew Gil was going to come up with. He was so steady that if he didn’t come up with a throw it made you wonder if he wasn’t feeling well that day.”

Meanwhile, Hodges’ Hall of Fame detractors suggest that his overall numbers were not particularly overwhelming (he batted just .273, scored only 1,105 runs, and compiled just 1,921 hits). They also point out that he never led the league in any major offensive category, and that he never came close to winning an MVP Award. Yet, if the Hall of Fame voters truly consider a candidate’s integrity and sense of sportsmanship when they cast their ballots, they will have to think long and hard before excluding Hodges’ name from their ballots.

Former New York Mets catcher Jerry Grote is one who certainly feels Hodges deserves a place in Cooperstown: “I wasn’t set as a ballplayer or a person until Gil Hodges came along. He settled me down and encouraged me to think. Gil stressed fundamentals…basic fundamentals. He always wanted you thinking out there. I don’t think any of us realized at the time the kind of effect Gil was having on us as men. But as you get older you realize things, and I know he made me a better individual in a lot of ways. He had an impact on everybody he touched. He got a lot of respect and he didn’t have to work for it because everybody knew what kind of man he was. He was a great baseball man, and a great human being.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Strange Things

Played For

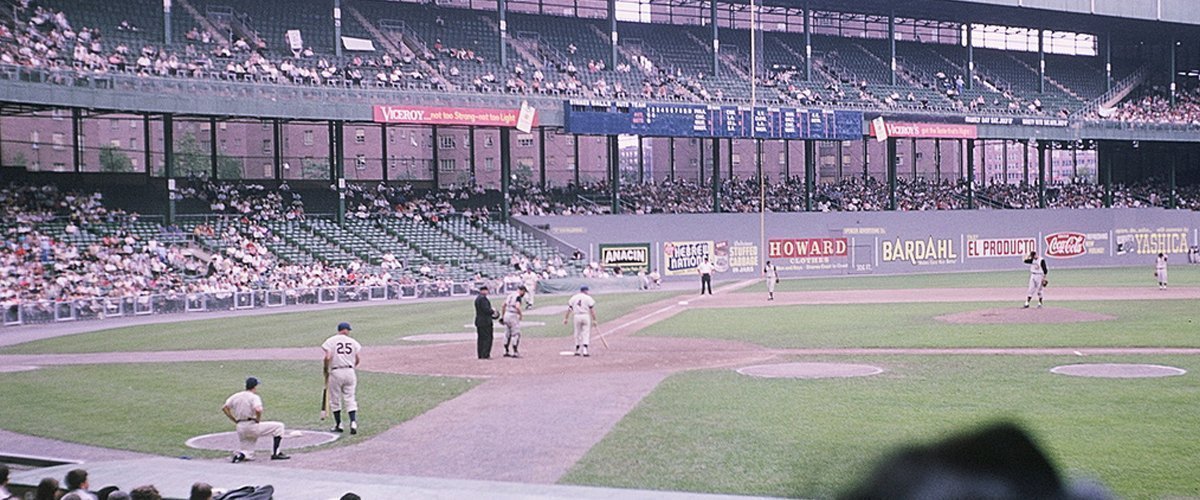

Brooklyn Dodgers (1943-1957)

Los Angeles Dodgers (1958-1961)

New York Mets (1962-1963)

Managed

Washington Senators (1963-1967)

New York Mets (1968-1971)

Similar: Tony Perez, Orlando Cepeda… Hodges has eerily similar stats to these two first basemen, who are both in the Hall of Fame. Hodges was, without question, a better defensive first baseman than either Perez or Cepeda… Hodges also compares well to another 1960s-era first sacker – Norm Cash, whose not enshrined in Cooperstown, and never will be.

Linked: Duke Snider

Best Season, 1954

Hodges drove in a career-high 130 runs.

Awards and Honors

1957 ML Gold Glove

1958 NL Gold Glove

1959 NL Gold Glove

Post-Season Appearances

1947 World Series

1949 World Series

1952 World Series

1953 World Series

1955 World Series

1956 World Series

1959 World Series

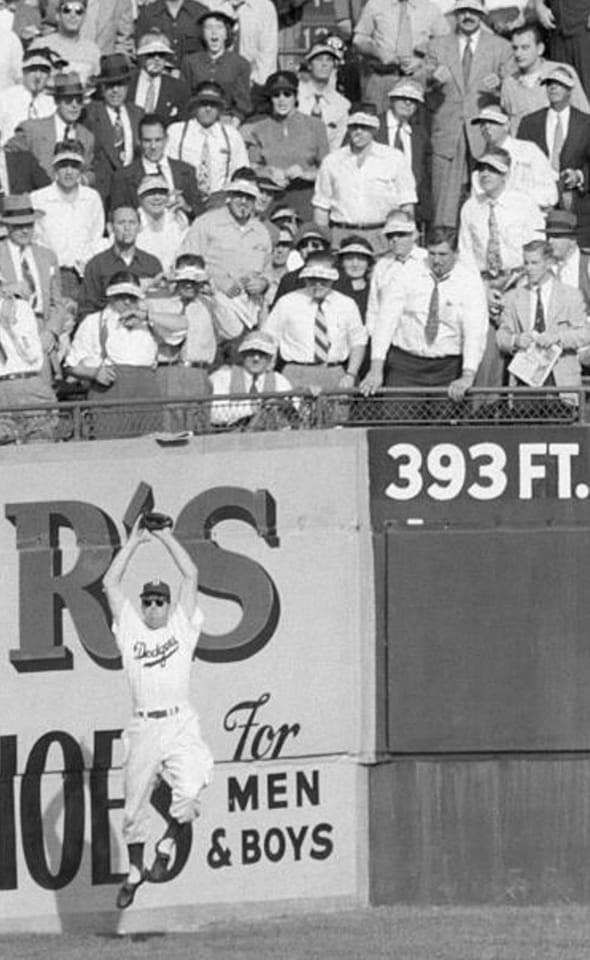

Where He Played: When injuries opened a hole in left field in the 1950s, the Dodgers tried Hodges out there for a few games.

All-Star Selections

1949 NL

1950 NL

1951 NL

1952 NL

1953 NL

1954 NL

1955 NL

1957 NL

Other Resources & Links