Josh Gibson – Biography

Josh Gibson

Positions: Catcher, Outfielder and First Baseman

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-1, 220lb (185cm, 99kg)

Born: December 21, 1911 in Buena Vista, GA

Died: January 20, 1947 in Pittsburgh, PA

Buried: Allegheny Cemetery, Pittsburgh, PA

High School: Allegheny HS (Pittsburgh, PA)

Debut: July 31, 1930, for the Homestead Grays

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1972. (Voted by Negro League Committee)

View Josh Gibson’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Joshua Gibson

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Other Players Who Debuted in 1930

Luke Appling

Joe Kuhel

Pinky Higgins

Ben Chapman

Hank Greenberg

Lon Warneke

Tommy Bridges

Lefty Gomez

Dizzy Dean

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology for Josh Gibson Career

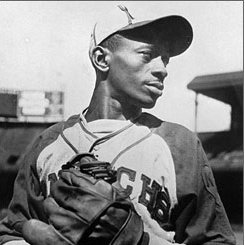

Second only to the legendary Satchel Paige among Negro League players in terms of fame and popularity, Josh Gibson is generally considered to be the greatest hitter in the history of black baseball. An almost mythical figure, Gibson was often referred to as the “Black Babe Ruth” during his playing days due to his tremendous power at the plate. Yet, those people who saw the Negro League catcher perform regularly preferred to think of Ruth as the “White Josh Gibson.” While statistics for Negro League players are far from reliable, Gibson reportedly won nine home-run titles and four batting championships during a 17-year career that began in 1930 and ended in 1946.

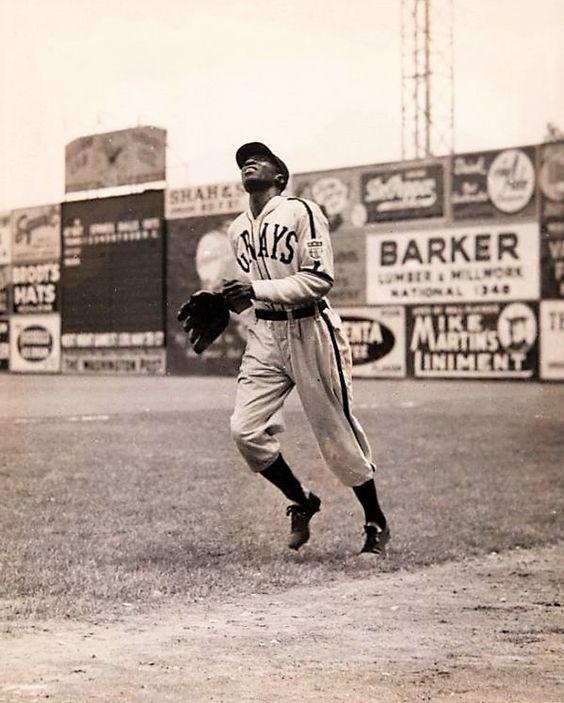

Born in Buena Vista, Georgia on December 21, 1911, Joshua Gibson moved with his family to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1923 after his father found work at the Carnegie-Illinois Steel Company. Gibson initially planned to become an electrician, attending Allegheny Pre-Vocational School and Conroy Pre-Vocational School as a sixth grader. However, he began to entertain thoughts of pursuing a career in baseball at the age of 16, after a job as an elevator operator at Gimbels department store led to a spot on an amateur team sponsored by the establishment. Gibson was recruited to play semi-professional ball shortly thereafter, before eventually being spotted by Cum Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays. Posey subsequently signed the 18-year-old to a contract with the Grays, and Gibson made his Negro League debut with the team on July 31, 1930.

Already a powerfully-built 6’1″ and 215 pounds at age 18, Gibson quickly established himself as one of black baseball’s most dynamic hitters. He batted .338 the remainder of the 1930 campaign, while serving as the Grays’ starting catcher. Gibson then began to perform the legendary feats that followed him the remainder of his career during a post-season series against the New York Lincoln Giants. According to John Holway in his Complete Book of the Negro Leagues, Gibson hit the first ball to clear the 457-foot centerfield fence in Forbes Field. Two days later, he hit a home run at New York’s Yankee Stadium that fellow Hall of Famer Judy Johnson said went over the roof in left field. Johnson’s account has never been fully corroborated, leaving doubt in everyone’s mind as to whether or not Gibson truly was the only man ever to hit a fair ball out of Yankee Stadium. Nevertheless, the clout was certainly majestic in nature, traveling somewhere in the vicinity of 500 feet.

Hitting mammoth home runs was not at all unusual for the barrel-chested Gibson. He once hit a home run in Monessen, Pennsylvania that was reportedly measured at 575 feet. The June 3, 1967 edition of The Sporting News credits Gibson with a home run struck in a Negro League game played at Yankee Stadium that struck two feet from the top of the wall circling the centerfield bleachers, some 580 feet from home plate.

Unfortunately, it is impossible to conclude just how accurate the stories surrounding Gibson’s feats actually are. Negro League statistics are extremely sketchy, and the level of their reliability is further compromised by the fact that they are generally intermingled with figures compiled in games played against other levels of competition. The Negro Leagues generally found it more profitable to schedule relatively few league games, thereby allowing the teams to earn extra money through barnstorming against semi-professional and other non-league teams. As a result, it is important to distinguish

between records compiled against all forms of competition, and those accumulated in league games only. For example, Gibson hit 69 home runs in 1934 against all levels of competition. However, he hit 11 homers in 52 games against other Negro League teams. The previous year, Gibson hit 55 home runs and compiled a .467 batting average in 137 games against all levels of competition.

Nevertheless, the fact remains that Gibson excelled against the competition he faced, and that he was a truly great hitter. Satchel Paige called him “the greatest hitter who ever lived.” And Monte Irvin, who played against Gibson in the Negro Leagues and later played with Willie Mays on the New York Giants, said: “I played with Willie Mays and against Hank Aaron. They were tremendous players, but they were no Josh Gibson. You saw him hit, and you took your hat off”.

Irvin also said of Gibson, “He had an eye like Ted Williams and the power of Babe Ruth. He hit to all fields.”

Splitting the majority of his career between the Negro Leagues’ two most dominant teams, the Homestead Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords, Gibson is estimated to have hit close to 800 home runs against Negro League and independent baseball opposition over the course of his 17-year playing career. Various reports also have him compiling a lifetime batting average somewhere between .359 and .384. Gibson reportedly batted over .400 in at least two seasons, and he posted a lifetime batting average of .351 in his 56 at-bats in exhibition games played against white major leaguers.

More than just a great hitter, Gibson was also very solid behind the plate. Although he was mediocre defensively early in his career, he improved that part of his game through the years. Teammate Cool Papa Bell said that, although Gibson occasionally had a difficult time with foul pops, he was a good catcher, had a strong arm, and was a good handler of pitchers.

Hall of Fame pitcher Walter Johnson stated, “There is a catcher that any big league club would love. His name is Gibson…he can do everything. He hits the ball a mile. Throws like a rifle. Bill Dickey isn’t as good a catcher.”

Fellow Hall of Fame hurler Carl Hubbell noted, “Yes sir. I’ve seen a lot of colored boys who should have been playing in the major leagues. First of all, I’d name this guy Josh Gibson for a place. He’s one of the greatest backstops in history, I think. Any team in the big leagues could use him right now.”

While Gibson certainly could have helped any major league team that elected to sign him, the unwritten rules of baseball kept him out of the majors his entire career. Feeling unfilled and frustrated over his inability to compete at the major league level, Gibson grew increasingly despondent through the years, occasionally lapsing into fits of rage and rambling outbursts. His level of discontent eventually became so deep that he turned to drugs and alcohol to relieve his anxiety. So troubled was Gibson that he experienced numerous nervous breakdowns, spending much of 1943 in a Washington D.C. sanitarium. Gibson fell into a coma after one such episode, after which he was diagnosed with a brain tumor. When he awoke, doctors wanted to surgically remove the tumor, but Gibson refused to grant them permission for fear that he might never recover. He returned to the playing field shortly thereafter, continuing to excel at his craft the next four seasons despite experiencing recurring headaches throughout the remainder of his career. Gibson died of a stroke at the age of 35 on January 20, 1947, just three months before Jackie Robinson broke major league baseball’s color barrier. Although the stroke is believed to be linked to the growing drug and alcohol problems he experienced in his later years, not everyone agreed. Longtime teammate and friend Jimmie Crutchfield often said that Gibson died of a broken heart at not having been allowed to play in the major leagues. The Negro Leagues’ greatest catcher was buried in the Allegheny Cemetery in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Lawrenceville. Gibson was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame 25 years later, in 1972.

Brooklyn Dodger great Roy Campanella spent several seasons competing against Gibson in the Negro Leagues before eventually joining Jackie Robinson in Brooklyn. Although Campanella made numerous Negro League All-Star teams, he was always rated behind Gibson as the leagues’ top catcher. Campanella expressed his admiration for his former opponent by calling him, “Not only the greatest catcher, but the greatest ballplayer I ever saw”.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon