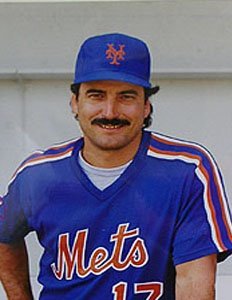

Keith Hernandez Stats & Facts

Keith Hernandez

Position: First Baseman

Bats: Left • Throws: Left

6-0, 180lb (183cm, 81kg)

Born: October 20, 1953 in San Francisco, CA

Draft: Drafted by the St. Louis Cardinals in the 42nd round of the 1971 MLB June Amateur Draft from Capuchino HS (San Bruno, CA).

High School: Capuchino HS (San Bruno, CA)

Debut: August 30, 1974 (13,550th in major league history)

vs. SFG 2 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: July 24, 1990

vs. CHW 4 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Full Name: Keith Hernandez

Nicknames: Mex

Twitter: @keithhernandez

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Notable Events and Chronology

Biography

Keith Hernandez

Considered by many baseball experts to be the greatest fielding first baseman in the history of the game, Keith Hernandez won more Gold Gloves (11) than any other player at his position. Possessing outstanding range, superb instincts, and tremendous self-confidence, Hernandez revolutionized first base play in much the same manner that Brooks Robinson changed the way the position of third base was defended. Hernandez established major league records for first basemen by leading his league in double plays six times. He also topped all N.L. first sackers in assists five times, putouts four times, and fielding average twice, while compiling the third most assists (1,682) of any first baseman in history. An outstanding hitter as well, Hernandez posted a lifetime batting average of .296 and a career on-base percentage of .384, leading the National League in both offensive categories one time. He also topped the senior circuit in runs scored twice, and in both doubles and walks once.

Biography:

Born in San Francisco, California on October 20, 1953, Keith Hernandez grew up in Pacifica and Millbrae, California. The son of a Mexican father and a Scots-Irish mother, Hernandez starred in baseball at Capuchino High School in San Bruno, from which he graduated in 1971. Despite excelling on the diamond his first two years at Capuchino, Hernandez received few college-scholarship offers since he developed a reputation for having a poor attitude after sitting out his entire senior year due to a dispute with a coach. He played briefly at the College of San Mateo, a local community college, before being selected by the St. Louis Cardinals in the 42nd round of the 1971 Major League Baseball Draft.

Although the 6’0”, 195-pound Hernandez displayed a strong affinity for playing first base early in his minor-league career, he failed to impress at the plate, compiling a batting average that hovered around the .250-mark in each of his first two seasons. The lefty-swinging Hernandez began to show improvement as a hitter in 1973, though, after being promoted to the Cardinals’ Triple-A affiliate in Tulsa. The first baseman batted .333 with five home runs and a .525 slugging percentage during the season’s second half, before hitting .351 for the Oilers over the first five months of the 1974 campaign. Hernandez’s increased offensive production earned him a promotion to St. Louis in late August. He appeared in 14 games for the Cardinals over the season’s final month, batting .294 and driving in the first two runs of his major-league career.

Hernandez split the 1975 season between Tulsa and St. Louis, batting just .250 for the Cardinals in just under 200 official at-bats, while also hitting three home runs and knocking in 20 runs. Nevertheless, he made a strong impression on St. Louis management with his exceptional fielding ability, committing only two errors in 507 chances, for an outstanding .996 fielding percentage.

Hernandez’s excellent glove work convinced the Cardinals to give him an opportunity to break into the team’s starting lineup the following year. Gradually establishing himself as the club’s regular first baseman over the course of the season, Hernandez batted .289, hit seven homers, and drove in 46 runs.

Hernandez developed into one of the National League’s top first basemen the following year, when he batted .291, hit 15 home runs, knocked in 91 runs, scored 90 others, and finished third in the senior circuit with 41 doubles. He had a less productive 1978 campaign, batting just .255, with only 11 homers and 64 RBIs. Still, he managed to win the first of his major-league record 11 consecutive Gold Gloves at first base.

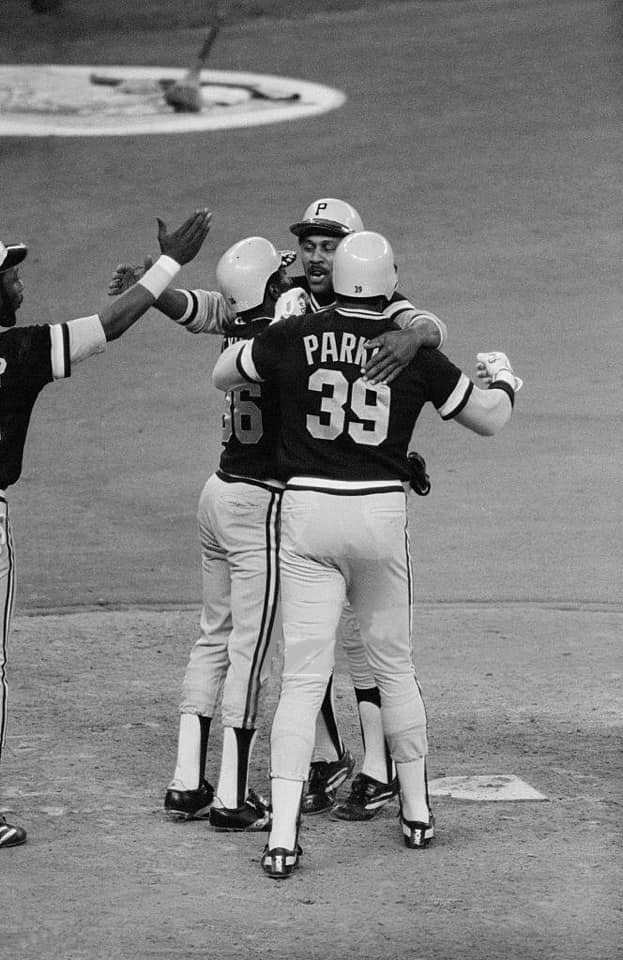

Hernandez took his game to the next level in 1979, batting a league-leading .344, driving in a career-high 105 runs, placing second in the senior circuit with 210 hits and a .417 on-base percentage, and leading the league with 116 runs scored and 48 doubles. The 25-year-old first baseman’s brilliant year earned him his first All-Star nomination and a first-place tie with Pittsburgh’s Willie Stargell in the league MVP voting.

Hernandez also played extremely well for the Cardinals in each of the next three seasons, performing particularly well in 1980, when he batted .321, hit 16 home runs, knocked in 99 runs, and led the National League with 111 runs scored. The first baseman helped lead St. Louis to the world championship in 1982, a year in which he batted .299 and drove in 94 runs during the regular season. He then excelled during the postseason, batting .333 against the Braves in the NLCS, before hitting a homer and knocking in eight runs during the Cardinals’ seven-game triumph over the Milwaukee Brewers in the World Series.

However, Hernandez’s relationship with Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog grew increasingly hostile during the early 1980s, a period during which the first baseman developed an addiction to cocaine. Herzog, who eventually came to view the free-spirited Hernandez as a cancer to his team, finally decided to part ways with arguably the Cardinals’ best player on June 15, 1983, trading him to the last-place New York Mets for pitchers Neil Allen and Rick Ownbey. After being criticized for accepting less-than-equal value from the Mets for the All-Star first baseman, Herzog attempted to defend the deal by hinting at Hernandez’s use of drugs. Hernandez threatened a libel suit, but the Pittsburgh drug trials held two years later substantiated Herzog’s remarks. The St. Louis manager never regretted making the trade, replacing Hernandez at first base shortly thereafter with fellow All-Star Jack Clark and winning two more pennants in the next four years.

Meanwhile, Hernandez initially balked at the idea of coming to New York. Rapidly approaching his 30th birthday, the veteran first baseman had no desire to continue his career with a team that had consistently finished at the bottom of the league standings the previous few seasons. The Mets’ front office, though, allayed many of Hernandez’s fears when it revealed to him the names of several outstanding young players it had coming up through its farm system. Assured by team management that exceptional young talents such as Dwight Gooden and Darryl Strawberry would soon be joining him on the Mets roster, Hernandez decided to adopt a wait-and-see attitude.

Hernandez’s decision eventually proved to be a wise one. Not only did the Mets soon become a contending team, but the first baseman found playing in the city of New York very much to his liking. Re-energized by the change in scenery and quite comfortable with the celebrity status he quickly attained in the Big Apple, Hernandez became a New York icon. He enjoyed the city’s nightlife, became a fixture at Manhattan’s most popular clubs, and dated celebrities, all while excelling on the ball field. He batted .306 in 95 games with his new team, helping the Mets reach a new level of respectability in the process. Furthermore, Hernandez developed into New York’s leader on the field almost as soon as he arrived, displaying a level of intensity he often was accused of lacking in St. Louis.

The Mets contended for the N.L. East title for the first time in a decade in 1984, with Hernandez’s presence in the team’s everyday lineup proving to be a huge factor. The first baseman batted .311, hit 15 homers, knocked in 94 runs, and placed among the league leaders with 97 walks and a .409 on-base percentage. He also provided a tremendous amount of leadership to his young teammates, a fact that did not go unnoticed by the baseball writers, who placed him second to Chicago’s Ryne Sandberg in the league MVP voting.

New York fell just short of capturing the division title the following year, placing a close second to Whitey Herzog’s St. Louis Cardinals. Hitting third in the Mets’ batting order, immediately in front of sluggers Gary Carter and Darryl Strawberry, agreed with Hernandez, who had another fine year. The All-Star first baseman batted .309 and knocked in 91 runs, en route to earning an eighth-place finish in the league MVP balloting. An exceptional clutch hitter who knew how to work the count, Hernandez set a single-season major league record by amassing 24 game-winning RBIs.

The Mets dominated the National League in 1986, capturing the division title in easy fashion. Hernandez finished fourth in the league MVP voting after batting .310, knocking in 83 runs, scoring 94 others, and leading the league with 94 bases on balls during the regular season. New York went on to capture the world championship, defeating Houston in the NLCS and squeaking by Boston in a classic seven-game World Series. Although Hernandez struggled somewhat at the plate in both series, his leadership and on-field presence once again proved to be invaluable.

Perhaps even more important than the leadership Hernandez provided to his teammates was the brilliant defense he turned in on a nightly basis. Committing a total of only nine errors in the field from 1985 to 1986, Hernandez gained widespread recognition as the finest defensive first baseman in the game. In addition to his sure hands, Hernandez had great range, tremendous intelligence, a strong and accurate throwing arm, and a total lack of fear. He charged attempted sacrifice bunts with abandon, completely taking away from the batter the entire right side of the infield in such situations.

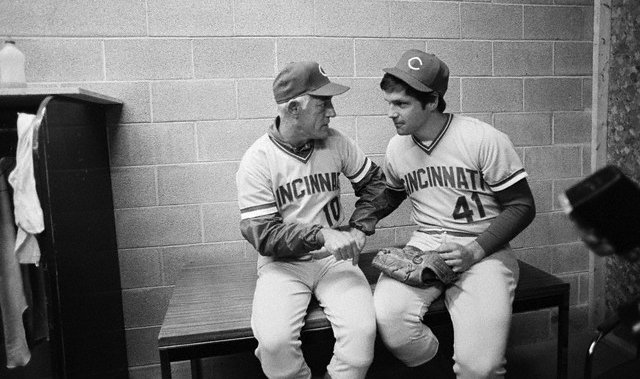

Pete Rose, when he managed the Cincinnati Reds, compared bunting against Hernandez to “driving the lane against Bill Russell.”

Astros manager Hal Lanier said the combination of Hernandez at first and any one of three Mets pitchers – Ron Darling, Roger McDowell or Jesse Orosco – made bunting against the Mets “near impossible.”

Meanwhile, Cubs manager Jim Frey revealed he wouldn’t ask most pitchers to bunt against the Mets, stating, “You’re just asking for a force-out at second, and now you’ve got your pitcher running the bases.”

The Mets named Hernandez the first team captain in franchise history prior to the start of the 1987 campaign. The first baseman responded by batting .290, hitting 18 homers, driving in 89 runs, and winning his 10th consecutive Gold Glove. However, the 1987 season turned out to be Hernandez’s last productive year. He missed a significant portion of 1988 with hamstring problems, then sat out much of 1989 with a bad knee. Furthermore, the ability of the veteran first baseman to properly lead his younger Mets mates began to come into question when the team failed to return to the World Series in either 1987 or 1988.

The Mets gradually developed a reputation during Hernandez’s tenure with the team for partying just as hard off the field as they played on it. Hernandez, whose past transgressions became public knowledge by the time the Mets established themselves as a National League powerhouse, became the poster-boy for the team’s often raucous behavior. New York’s failure to live up to its full potential caused many a finger to be pointed in the direction of Hernandez, who lost even more credibility when he found himself unable to take the field much of the time his last two years with the team. A well-publicized confrontation with Darryl Strawberry, who perhaps admired Hernandez more than anyone else on the team at one point, essentially marked the beginning of the end for the first baseman in New York. The Mets chose not to re-sign their 36-year-old captain when his contract expired at the conclusion of the 1989 season, making Hernandez a free agent. He subsequently signed with the Cleveland Indians, with whom he spent the 1990 campaign before announcing his retirement at the end of the year. Hernandez left the game with 1,071 runs batted in, 1,124 runs scored, 2,182 hits, a lifetime batting average of .296, and a career on-base percentage of .384. He knocked in more than 90 runs six times, scored more than 100 runs twice, batted over .300 seven times, and compiled an on-base percentage in excess of .400 on seven separate occasions. Hernandez appeared on the National League All-Star Team five times and placed in the top 10 in the league MVP voting four times.

After retiring from the game as an active player, Hernandez turned to broadcasting, eventually earning a spot as a color commentator on New York Mets’ television broadcasts. He continues to serve in that capacity.