Municipal Stadium

Municipal Stadium, Kansas City, MO

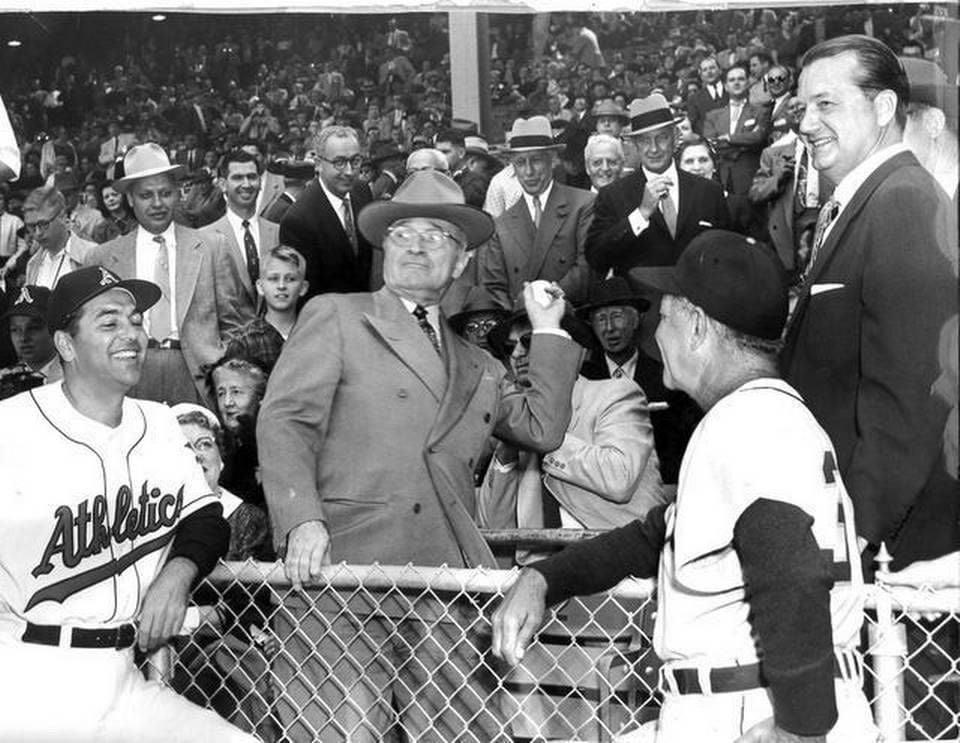

Ball Park First Game

Date – 04/12/1955 (1)

Starting Pitchers – vs. Tigers: 04/12/1955

Final Score 6-2 (KCA)

Attendance – 32,147

Starting Pitchers Alex Kellner (KCA); Ned Garver (DET)

First Batter – Harvey Kuenn (DET) Result – Flied to RF

First Hits – Fred Hatfield (DET),Doubled to RF (1st)

First Run – Bill Wilson (KCA)

First RBI – Joe DeMaestri (KCA)

First Homerun – Red Wilson (DET) vs. Alex Kellner (KCAA) on 04/12/1955 (5th inning)

First Grandslam – Jim Hegan (CLE) vs. Bill Harrington (KCA) on 08/12/1955 (1st inning)

First Inside Park Homerun – Bob Cerv (KCA) vs. Cal McLish (CLE) on 04/22/1958 (3rd inning)

First No Hitter – None

Ball Park Lasts

Last Game – vs. Rangers: 10/04/1972, Final Score – 4-0 (KCA)

Attendance – 7,329

Starting Pitchers – Roger Nelson (KCA); Don Stanhouse (TEX), Winning Pitcher – Roger Nelson (KCA) Losing Pitcher – Don Stanhouse (TEX)

Last Batter – Ted Ford (TEX), result – Lined to CF

Last Hit – Ed Kirkpatrick (KCAR), Singled to LF (8)

Last Run – Amos Otis (KCAR), Last RBI – Lou Piniella (KCAR)

Last HR – Gene Tenace (OAK) vs. Monty Montgomery (KCAR) on 09/30/1972 (4th inning)

Last Grand Slam – Terry Crowley (BAL) vs. Roger Nelson (KCA) on 07/23/1972 (7th inning)

Last Inside The Park Homerun – Freddie Patek (KCA) vs. Mike Kilkenny (DET) on 07/18/1971 (6th inning)

Last No Hitter – None

TRIVIA –

On July 13, 1963 Indians hurler Early Wynn won his 300th and final game of his career with a 7-4 win over the A’s; On September 8, 1965 Kansas City’s Bert Campaneris became the first player to play all nine positions in a game.

FIRST IMPRESSION

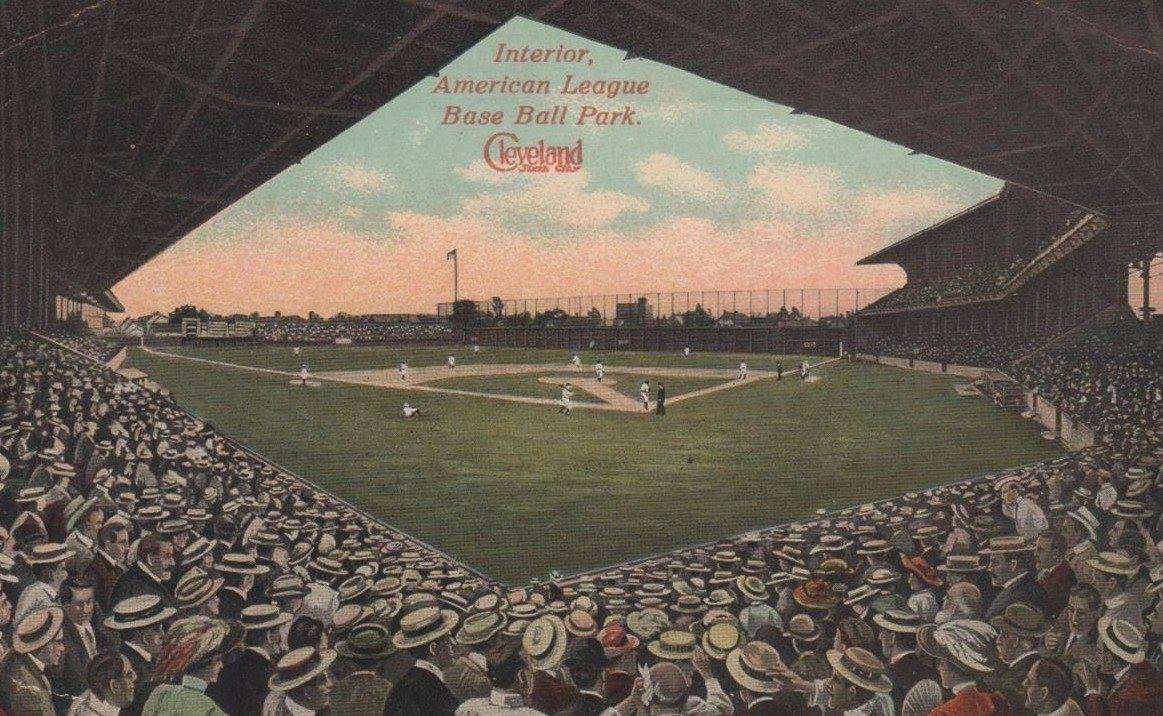

You have to admire its perseverance, a tired, old concrete-and-steel edifice that stood up to a depression, a burning river, economic turmoil, bad baseball and the ill winds that blow relentlessly off Lake Erie. Municipal Stadium was a tough old bird, massive, imposing and scarred from years of neglect and abuse. It also was a proud remnant of a bygone era, when ballparks were measured as much by size and function as by charm and charisma.

Imposing had given way to clunky and awkward by 1993, when the stadium finally closed its gates to baseball after more than six decades. But through most of its existence, it had been a perfect match for a tough, no-frills, factory-dominated city in the middle of America’s iron belt. It was huge, unpretentious and lacking in the physical quirks and nuances that gave other early-era ballparks personality. It was, in the truest sense, a stadium — a downtown sports arena that survived 62 years of erratic lakefront weather without a lot of love or tender care.

You noticed quickly that Cleveland Stadium had not been pampered like Fenway Park or showered with Wrigley Field-like affection. This was a hulking, horseshoe-shaped fortress with a nondescript sandstone facade and protruding buildings that served as business and ticket offices. On a clear summer afternoon, with the sun glistening off Lake Erie, it looked like a big, beached white whale. The first sign of baseball life was an elevated welcome sign featuring a smiling, toothy Chief Wahoo, bat cocked and ready to smack a long one into the unpaved parking lot.

The smile was misguided. The inside concourses were dingy, damp, concrete walkways and corridors that circled and branched endlessly to points unknown. Bathrooms were tiny, concession stands were small and boxes were stacked in corners like the remainders of a past life stored in someone’s attic. The first sense of a grand stadium with a historic aura did not come until you reached the field area.

It was hard to get past that first, overwhelming feeling of huge. A double-decked, roofed grandstand filled with small, wooden seats rose up around you like a protective shield, giving you a sense of enclosure. But any claustrophobic fears were quickly relieved by the open center field, through which upper-deck fans on the right field side could get an angled view of the lake.

SIGNATURE FEATURES

At the open end were a big scoreboard and some of the most famous bleacher seats in sports — the infamous Dawg Pound section that tormented football opponents of the Cleveland Browns. For baseball, these bleachers were in dead center field, 470 feet from home plate, a target no batted ball ever reached.

The seats in the back row of the bleachers were farther away from home plate than any other seats in baseball and the scoreboard, more than 500 feet from fans behind the plate, was hard to see and a very basic blend of information and scores.

The original dimensions of the symmetrical field were imposing — 470 feet to center, 463 in the power alleys and 322 down both lines. But owner Bill Veeck installed a foul-line-to-foul- line inner fence in 1947 that cut the center-field distance to 410 and the power alleys to 385. The distances were tailored over the years to Indians talent, and the area between the fence and the bleachers was used for standing-room, a garden and eventually a family picnic grounds.

Economic hard times and weak teams hurt the Indians and lack of upkeep and renovation doomed the stadium, which was sarcastically dubbed “The Mistake by the Lake.”

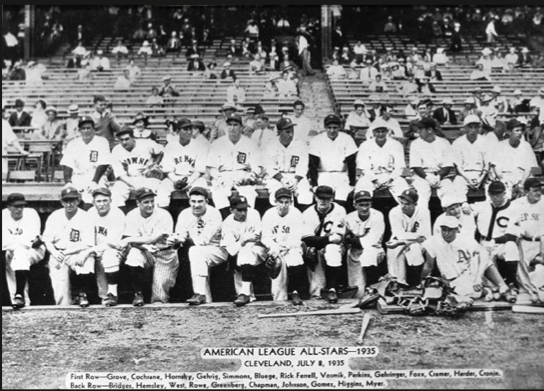

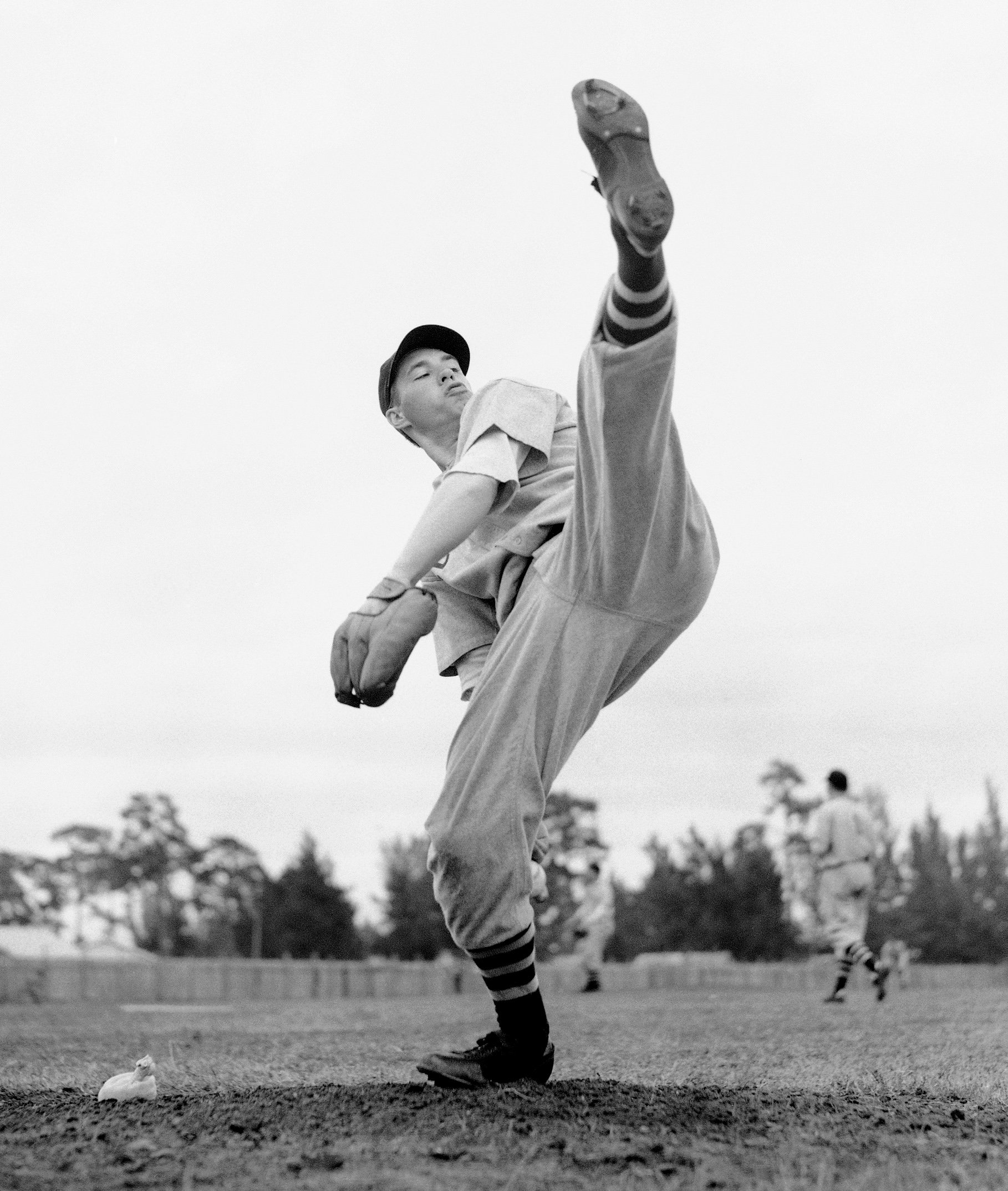

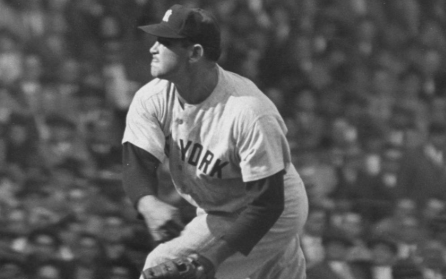

In retrospect, that’s harsh. While the stadium might have been lacking in physically distinctive features, it was easy to get lost in its history — the distinctive Bob Feller windup, the ghosts of Early Wynn, Mike Garcia, Bob Lemon and Feller, who pitched the Indians to an incredible 111 wins in 1954. Names like Doby, Rosen, Colavito, Easter, Averill, Wertz, Trosky, Thornton and, of course, Boudreau assaulted the brain like the rhythmic pounding of superfan John Adams’ excited drumbeats.

There’s no denying Cleveland Stadium lived most of its life as a haggard, worn-down super-structure from the 1930s — a charmless albatross to disbelieving visitors. But it’s also hard to deny Cleveland fans their special moments. There is, after all, no place like home.

QUOTABLE

“The stadium is perfect. It is the only baseball park I know where the spectator can see clearly from any seat. This is perfection.” — commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis