Orlando Cepeda Stats & Facts

Orlando Cepeda

Positions: First Baseman and Leftfielder

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-2, 210lb (188cm, 95kg)

Born: September 17, 1937 in Ponce, Puerto Rico

Debut: April 15, 1958 (11,518th in major league history)

vs. LAD 5 AB, 1 H, 1 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 19, 1974

vs. OAK 1 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1999. (Voted by Veteran’s Committee)

View Orlando Cepeda’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Orlando Manuel Cepeda

Nicknames: Cha Cha or Baby Bull

Pronunciation: \suh-PAY-duh\

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Other Players Who Debuted in 1958

Vada Pinson

Ron Fairly

Tony Taylor

Orlando Cepeda

Norm Cash

Felipe Alou

Mudcat Grant

Frank Howard

Jerry Adair

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology

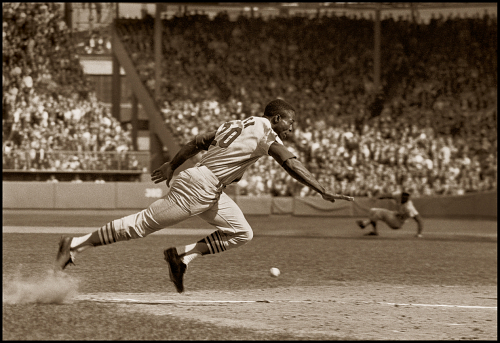

A slugger in the truest sense of the word, Orlando Cepeda intimidated opposing pitchers with his tremendous physical strength that enabled him to drive a ball out of any part of the park. Standing 6’2” and weighing close to 220 pounds, the man nicknamed “The Baby Bull” presented an imposing figure when he stepped into the batter’s box. Yet, Cepeda was more than just a power hitter. He consistently batted over .300 and also finished in double-digits in stolen bases during the early stages of his career, before knee problems significantly reduced his playing time and severely limited his effectiveness on the base paths. A difference-maker both on the field and in the clubhouse, Cepeda helped improve the fortunes of three different teams over the course of his 17 major league seasons, leading two to National League pennants and one to a world championship. Still, Cepeda’s fall from grace following his playing days, as well as his eventual resurrection to Cooperstown, serve as a poignant reminder of the extremely transient nature of the life of a professional sports star.

Biography:

Born in the southern seaport city of Ponce, Puerto Rico on September 17, 1937, Orlando Manuel (Penne) Cepeda grew up idolizing his father, Perucho, who reached legendary status in the Caribbean as a big, power-hitting shortstop. Sometimes referred to as the Babe Ruth of the Caribbean, the elder Cepeda was more commonly known as “The Bull.” Young Orlando learned to play the game of baseball from his father, who often took his son with him when he traveled throughout Latin America during his playing days. The younger Cepeda soon developed a strong desire to pursue a career in baseball as well, although he briefly lost interest after failing to make a local team. He refocused his attention on the sport he grew up playing after injuring his right knee playing basketball around the age of 13. Cepeda’s injury eventually required corrective surgery that included the removal of knee cartilage. Although the healing process was a lengthy one that kept Cepeda in bed for two months and on crutches for almost half a year, it ended up benefiting the 15-year-old since he added some 40 pounds of bulk during his recuperation period that he eventually converted into muscle. The added weight transformed the teenager from a skinny singles hitter into a powerful slugger.

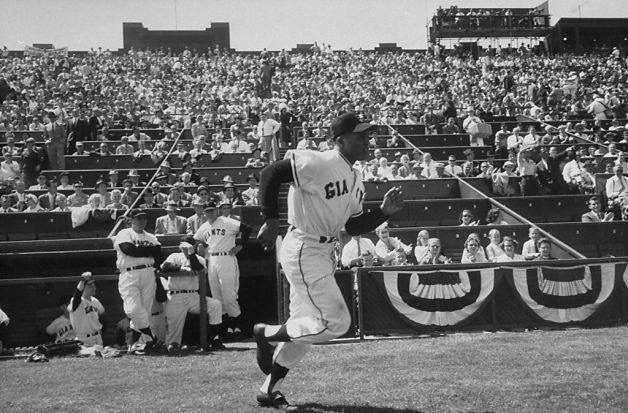

After watching Cepeda compete as an amateur, Pedro Zorilla, owner of the Santurce Crabbers, convinced the 17-year-old’s family to allow the youngster to travel to Florida to participate in a tryout for the New York Giants. Cepeda’s combination of power and speed very much impressed the Giants, prompting them to offer him a contract. Hitting with a closed stance, the young third baseman fared particularly well against high pitches, driving fierce line drives to all parts of the ballpark. Though somewhat flat-footed, he also ran like a deer. What he lacked in sure-handedness in the field, he made up for with his exuberance and willingness to learn.

The Giants assigned Cepeda to the Salem Rebels, a Class D team in the southern Appalachian League. Shortly after he arrived in Salem, Cepeda learned that his father had succumbed to a stomach disorder. After attending the funeral in Puerto Rico, Cepeda seriously considered quitting baseball and remaining in his homeland. Crestfallen over the loss of his father, lonely due to his inability to speak English, and upset with the treatment he received in the still racially-segregated south, Cepeda struggled in his time at Salem. After hitting just one home run in 26 games for the Rebels, Cepeda was transferred by the Giants to Kokomo, a new team in the struggling Mississippi–Ohio Valley League.

Playing third base and batting fourth for the Kokomo Giants, Cepeda came to realize his full potential. Although his exaggerated closed stance left him somewhat vulnerable to quality pitches low and inside, he ended up hitting 21 home runs, driving in 91 runs, and batting .393. Cepeda spent the next two years advancing through the Giants’ farm system, while learning how to play first base.

The Giants added Cepeda to their major league roster prior to the start of the 1958 campaign – their first after leaving New York for the West Coast. After winning the starting first base job in spring training, Cepeda went on to capture National League Rookie of the Year honors by hitting 25 home runs, driving in 96 runs, batting .312, and topping the circuit with 38 doubles. The 21-year-old first baseman so impressed Giants manager Bill Rigney that the latter later called him “the best young right-handed power hitter I’d seen.”

Cepeda also made an extremely favorable impression on Giants fans. Since the rookie joined the team in its first year on the West Coast, San Francisco fans adopted Cepeda as one of their own. In fact, they accepted him far more easily than Willie Mays, who they viewed more as a New Yorker. As a result, Mays held inside him for many years a certain amount of resentment towards Cepeda for the favored treatment the latter received from fans of the team.

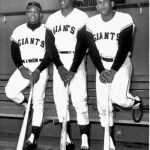

Cepeda followed up his outstanding rookie season with an even better sophomore campaign, placing among the league leaders with 27 home runs, 105 runs batted in, 192 hits, 35 doubles, and a .317 batting average. He even finished second in the league to teammate Mays in stolen bases, with 23. The midseason arrival of slugging rookie first baseman Willie McCovey prompted the Giants to move Cepeda to left field for much of the season’s second half. Though unhappy about the defensive shift that often caused him to look somewhat amateurish, Cepeda found himself unable to complain since McCovey won Rookie of the Year honors by batting .354, hitting 13 home runs, and driving in 38 runs, in just under 200 official at-bats.

After spending their first two years in San Francisco playing in Seals Stadium, the Giants moved into Candlestick Park in 1960. The swirling winds at the team’s new home ballpark made it extremely difficult for right-handed hitters to drive the ball over the left field fence, prompting Cepeda to change his batting style. Previously a pull hitter, Cepeda opened up his stance and began driving the ball more to right and right-center. Splitting his time between the outfield and first base, he ended up hitting 24 homers, knocking in 96 runs, and batting .297.

Cepeda had his finest statistical season in 1961, a year that became known for its tremendous offensive production. With the American League expanding from eight to ten teams, several players of somewhat limited ability appeared on major league rosters, enabling stars such as Cepeda to flourish. Once again splitting his time between the outfield and first base, Cepeda led the National League with 46 home runs and 142 runs batted in, while also placing among the leaders with 105 runs scored, a .311 batting average, and a .609 slugging percentage. Cepeda’s outstanding year earned him a spot on the All-Star Team for the third straight season and a second-place finish to Cincinnati’s Frank Robinson in the league MVP voting.

Still, the 1961 campaign had its dark moments for Cepeda. After reinjuring his right knee in a home plate collision with Dodger catcher John Roseboro, Cepeda never again played entirely pain-free. Furthermore, the injury drove a wedge between Cepeda and Alvin Dark, who took over as Giants manager the previous season. Dark, who Cepeda never felt respected him or his Spanish-speaking teammates, accused the slugger of putting forth less than a 100 percent effort after he hurt his knee against Los Angeles. The San Francisco manager was quoted on one occasion as saying, “I’m sick and tired of players on this team leading the league in home runs and RBIs and not doing anything to help us win!” Although Dark apologized to Cepeda years later for not taking his injury more seriously, his ill-advised comment exacerbated any feelings of animosity Cepeda may have already had towards him.

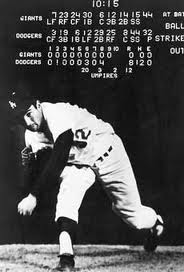

Cepeda aggravated his knee while working out with weights during the subsequent off-season, but he hid his injury from the team since he had no desire to evoke further criticism from Dark. Playing 160 games at first base and another two in the outfield, Cepeda helped the Giants capture the National League pennant by hitting 35 home runs, driving in 114 runs, scoring 105 others, and batting .306. Although he struggled against the Yankees in the World Series, New York respected him enough to pitch to Willie McCovey with Game Seven on the line and Cepeda standing in the on-deck circle. With two men out in the bottom of the ninth inning, runners on second and third base, and the Yankees holding a slim 1-0 lead, McCovey hit a blistering line drive right at second baseman Bobby Richardson that gave the Yankees their second straight world championship.

Cepeda had similarly productive years in both 1963 and 1964, combining for 65 home runs and 194 runs batted in, while posting batting averages of .316 and .304, respectively. However, after playing first base almost exclusively the previous three seasons, Cepeda moved to left field at the start of 1965 at the behest of new Giants manager Herman Franks, who believed that playing McCovey at first base would benefit the team.

Diving for a ball early in the year, Cepeda injured his right knee again, essentially ending his season and severely limiting his mobility the remainder of his career. He appeared in a total of only 33 games over the course of the season, mostly as a pinch-hitter, hitting only one home run and driving in just five runs.

After having his knee surgically repaired during the off-season, Cepeda performed various types of manual labor to strengthen the joint and stay in shape. He returned to the Giants in the spring asking to play first base, but was told by manager Franks that he intended to use McCovey at first instead. Despite asking to be traded, Cepeda began the 1966 campaign in left field for the Giants, until the team finally dealt him to St. Louis in early May for left-handed starter Ray Sadecki. Cepeda played first base and batted cleanup for the Cardinals the remainder of the year, leading the team with 17 home runs, 24 doubles, a .303 batting average, and a .469 slugging percentage, despite appearing in only 123 games for them. His outstanding performance in St. Louis earned Cepeda Comeback Player of the Year honors.

Cepeda reached the pinnacle of his career in 1967, capturing N. L. MVP honors by leading the Cardinals to the league championship. Serving as the team’s primary power threat and inspirational leader in the clubhouse, the first baseman brought together a talented group of players that needed to learn how to win. Cepeda hit 25 home runs playing in Busch Stadium, a notoriously bad park for hitters. He also batted .325, scored 91 runs, amassed 37 doubles, and led the league with 111 runs batted in. Although a few other players in the senior circuit posted numbers that rivaled the figures Cepeda compiled over the course of the season, no one else made more of an impact on his respective team. The baseball writers recognized that last fact by naming Cepeda the first unanimous MVP winner in the National League.

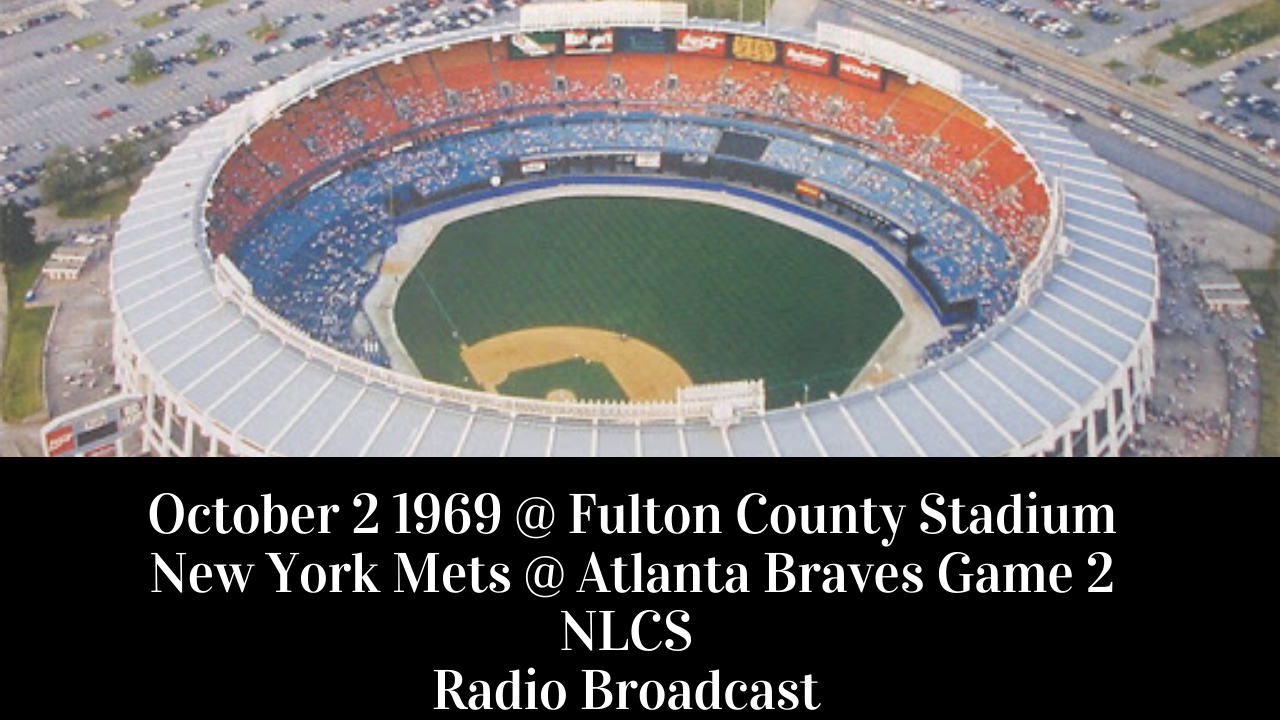

Cepeda spent only one more year in St. Louis, being dispatched to Atlanta for Joe Torre after hitting only 16 home runs, driving in just 73 runs, and batting only .248 in 1968, which came to be known as The Year of the Pitcher. The first baseman had two productive years for the Braves, faring particularly well in 1970, when he hit 34 homers, knocked in 111 runs, and batted .305.

Cepeda’s days as a full-time player all but ended in 1971 when he freakishly injured his left knee in early May. Rising from a chair in his living room to answer the telephone, Cepeda felt his knee give out. He played through pain the next few weeks, before finally electing to have season-ending surgery.

Cepeda returned to the Braves in 1972 but found it increasingly difficult to play the field on his aching knees. After appearing in only 28 games for Atlanta through midseason, Cepeda was traded to Oakland for former A.L. Cy Young Award winner Denny McLain and cash. He made only three pinch-hit appearances for the A’s before his left knee gave out again. He underwent his second surgery in a year and missed the remainder of the season, failing to take part in Oakland’s World Series celebration.

It appeared that Cepeda’s career might be over when Oakland released him during the offseason, but the Boston Red Sox signed the 35-year-old slugger as a free agent one month later after the American League announced it intended to use a designated hitter in its games beginning in 1973. Despite limping noticeably whenever he stepped onto the field, Cepeda hit 20 home runs, drove in 86 runs, and batted .289 for the Red Sox in 142 games, en route to earning DH of the Year honors.

In spite of his solid season, Cepeda failed to make Boston’s roster in 1974 when new manager Darrell Johnson decided to embark on a youth movement. After spending the first part of the year with the Yucatan Lions in the Mexican League, Cepeda signed on with the Kansas City Royals when the team’s regular DH Hal McRae suffered an injury in early August. Cepeda finished out the year as Kansas City’s regular DH, hitting only one home run and batting just .215. He announced his retirement at season’s end, finishing his career with 379 home runs, 1,365 runs batted in, 1,131 runs scored, 2,351 hits, and a .297 batting average. Cepeda surpassed 20 homers on 12 separate occasions, reaching the 30-mark five times. He also knocked in 100 runs five times, scored 100 runs three times, and batted over .300 nine times. Cepeda earned seven selections to the National League All-Star Team.

Despite the impressive numbers Cepeda compiled during his career, he had a difficult time gaining admittance to Cooperstown. The only eligible player from 1981 to 1993 with more than 300 home runs and a lifetime batting average of at least .295 not to be elected to the Hall of Fame, Cepeda fell just seven vote shorts of enshrinement in his final year of eligibility.

Certainly, Cepeda’s off-field transgressions were at least partly responsible for his initial exclusion from the Hall of Fame. Returning from a baseball clinic in Colombia in 1975, Cepeda was arrested at the San Juan Airport after police found 170 pounds of marijuana in his luggage. The police subsequently charged him with drug possession.

After two years of unsuccessful legal maneuvering, the courts found Cepeda guilty and sentenced him to five years of imprisonment. While still on trial for that charge, Cepeda’s reputation suffered further damage when he was arrested after a man alleged that the former major leaguer had pointed a gun at him.

Cepeda served ten months in jail time and the balance of his sentence on probation. However, following his release, a district attorney in Puerto Rico told the prison’s warden that the mafia intended to kill Cepeda if he returned to his homeland. As a result, the former N.L. MVP found himself assigned to a “halfway house” in Philadelphia. Disgraced in his homeland and divorced for a second time, Cepeda had hit rock-bottom.

Displaying the same determination he carried with him on the ball field, Cepeda gradually began to rise from the dead. After completing the program at the “halfway house,” he coached a LBPPR team in Bayamon, Puerto Rico, before being hired by the Chicago White Sox, first as a hitting instructor and later as a scout. He also opened a baseball school in San Juan.

Cepeda moved back to the United States in 1984, settling in Los Angeles, where he tutored young hitters with professional aspirations. However, his reputation as a convicted drug offender continued to haunt him. While renewing acquaintances at Dodger Stadium during batting practice, he was ejected by security. The team did not want him in the ballpark.

Shortly thereafter, Cepeda’s third wife, Mirian, encouraged him to turn to Buddhism to deal with the anger and shame he felt. She also suggested they move back to Northern California, where Cepeda remained popular with the fans who once embraced him as one of their own. They relocated in 1986, and in 1987 the Giants hired Cepeda for a Community Relations position. He moved into scouting and player development for the club and eventually became a sort of goodwill ambassador for the organization.

Failing to gain admittance to Cooperstown during his initial period of eligibility, Cepeda had his name removed from the Hall of Fame ballot after 1993. However, the members of the Veterans Committee elected him in 1999. Nine years later, the Giants erected a nine-foot bronze statue in his honor outside AT&T Park. Joining fellow Giants legends Willie Mays, Willie McCovey, and Juan Marichal as one of only four players to be so honored, Cepeda reached a point in his life he undoubtedly thought unattainable just a few years earlier.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon