Paul O’Neill Stats & Facts

Paul O’Neill

Position: Rightfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Left

6-4, 200lb (193cm, 90kg)

Born: February 25, 1963 in Columbus, OH us

Draft: Drafted by the Cincinnati Reds in the 4th round of the 1981 MLB June Amateur Draft from Brookhaven HS (Columbus, OH).

High School: Brookhaven HS (Columbus, OH)

School: Otterbein University (Westerville, OH)

Debut: September 3, 1985 (15,090th in major league history)

vs. STL 1 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: October 7, 2001

vs. TBD 3 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Full Name: Paul Andrew O’Neill

Nicknames: The Warrior

Twitter: @PaulONeillYES

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1985

Andres Galarraga

Paul O’Neill

Ozzie Guillen

Devon White

Jose Canseco

Cecil Fielder

Teddy Higuera

Shawon Dunston

Todd Worrell

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology

Biography

Like most sweet-swinging lefthanded batters, Paul O’Neill drew comparisons to the legendary Ted Williams in his youth. Although he once carried a .400 batting average into mid-June, it was the intensity — and at times rage — that O’Neill brought to his at-bats which most reminded people of the “Splendid Splinter.”

A direct descendant of Mark Twain, O’Neill was born in 1963 in Columbus, Ohio. In high school he was primarily a pitcher, and he earned All-State honors in both baseball and basketball. After being drafted by Cincinnati, O’Neill rose rapidly through the Reds’ farm system and made his major league debut on September 3, 1985, singling on the first pitch he saw from Jeff Lahti. Eight days later he watched from the bench as Pete Rose collected his record-setting 4,192nd hit.

O’Neill’s career hit a pothole in 1986 when he tore ligaments in his thumb while attempting a diving catch, an injury which limited him to 55 games at Triple-A Nashville and just three games with the Reds. After playing 84 games in 1987 as the Reds’ top pinch-hitter, O’Neill moved into an everyday role the following season and never looked back. An integral part of the 1990 World Champion club, O’Neill hit .270 with sixteen home runs and finished second on the team to Eric Davis with 78 RBIs.

In his first three years with Cincinnati, O’Neill matured into an excellent outfielder, but the Reds wanted him to hit with more power. In 1991, O’Neill responded by belting a career-high 28 home runs and driving in 91 runs. But the emphasis on the long ball came at the expense of the 28-year-old’s development as an all-around hitter. O’Neill’s average dropped to .256 and he struck out a career-high 107 times. When he slipped to .246 with just fourteen home runs in 1992, the Reds were convinced that his best days were already behind him.

O’Neill’s career took a dramatic turn in November of 1992, when Reds GM Jim Bowden traded him to the New York Yankees for outfielder Roberto Kelly. With a power-laden lineup that featured sluggers Danny Tartabull and Mike Stanley, the Yankees didn’t ask O’Neill to swing for the fences and the young outfielder began hitting the ball to all fields. “When you’re 6′ 4” and you hit some balls out, everybody’s thinking that you’re a home run hitter,” O’Neill said. “And you try to do that more. But for me to try to pull an outside pitch — that’s not me. I see people do that and wonder how they’re able to. I can’t go up there thinking ‘hit the ball to right field’.”

Ironically, O’Neill’s new approach sent his batting average soaring without hurting his power numbers. He hit 20 round-trippers in his first season in New York and after a career-low batting average in his final season with the Reds, O’Neill topped .300 for the first time with a .311 mark.

The following season, O’Neill showed the numbers he was capable of producing. He opened the season hitting .448 in April and followed that up with a .410 May. O’Neill didn’t drop below .400 until June 17th. When the players’ strike ended the season on August 14th, it ruined great seasons for both O’Neill, who was batting a league-high .359, and for the Yankees, who owned a league-best 70-43 record.

Although his production pleased the Yankees and their fans, O’Neill never seemed capable of satisfying himself. In many ways he was ill-suited to the particular demands of baseball, a sport where failing twice in three tries counts as great success. When he couldn’t come up with a necessary hit or perform to his expectations, O’Neill brooded incessantly or took out his rage on his batting helmet or any other dugout objects which he found in his path. Often O’Neill would drop his head when he left the batter’s box after making poor contact, as if ashamed of himself. At times his standard of perfection went to such outrageous lengths that he could be seen bowing his head even after pitches he hadn’t hit quite right ended up in the first rows of the left field corner bleachers for a well-placed home run.

He was his own severest critic. In his first six seasons with New York, O’Neill always hit at least .300. Although he never developed into a major power threat, he was one of the most frightening hitters in the American League. His well-built frame and vicious swing made it look as if he could easily launch balls into the far reaches of the bleachers, and his prowess with men on base justified the respect pitchers afforded him.

Two great playoff moments burned indelible images of O’Neill into the minds of Yankee fans. Toward the end of the 1996 season, O’Neill had been hampered by a sore hamstring that limited his effectiveness both at the plate and in the field. Although he ended the year with a solid .302 average, he was not the lethal hitter that people were accustomed to seeing. In the Yankees’ three post-season series, O’Neill managed just seven hits in 38 at bats, and at times seemed to survive on sheer competitiveness alone.

Although O’Neill was visibly slowed and in pain, manager Joe Torre left him in the lineup in the belief that he could produce when it mattered most. O’Neill justified Torre’s faith in the bottom of the ninth inning of Game Three of the World Series, when closer John Wetteland and the Yankees clung to a 1-0 lead with the Series tied at two games apiece.

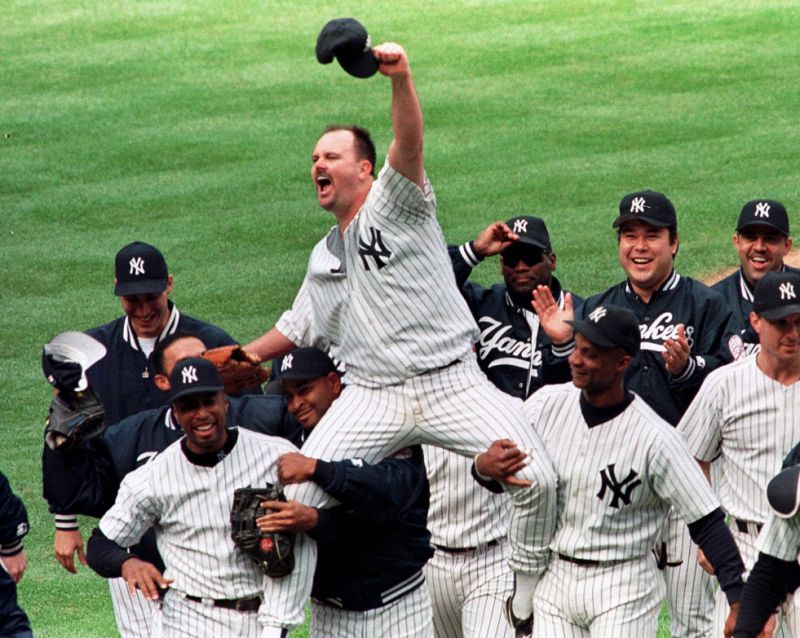

With two outs and runners on the corners, Luis Polonia ripped a Wetteland offering toward the right centerfield alley. For a few moments it seemed like Torre had made the same blunder as John McNamara, who in the 1986 World Series let Bill Buckner stay at first base instead of defensive replacement Dave Stapleton for the fateful tenth inning of Game Six. But, limping as much as running, O’Neill willed himself into the ball’s path and at the last fully extended his arm and glove to snare the line drive. His catch — the final out recorded in Atlanta’s Fulton County Stadium — prevented two runners from scoring easily and gave the Yankees a 3-2 lead in the Series. With the ball safely tucked in his glove, O’Neill pounded the outfield wall and let loose a primal scream of exultation as his teammates mobbed him.

The following year, O’Neill arrived at the post-season in full strength. He had just completed a season that saw him bat .324 with a career-high 117 runs batted in, and in which he batted a league-best .428 with runners in scoring position. In Game One of the Division Series against Cleveland at Yankee Stadium, O’Neill followed circuit blasts by teammates Tim Raines and Derek Jeter with yet another home run, marking the first time in post-season history that a team had hit three consecutive home runs. In Game Three at Jacobs Field he drove in five of the Yankees’ six runs and smashed a game-breaking grand slam off Chad Ogea in the fourth.

Yet most memorable was O’Neill’s at-bat in the top of the ninth with the Yankees behind 4-3 in the Series’ decisive fifth game. With one out separating New York from the offseason, O’Neill rocketed a Jose Mesa fastball to dead centerfield. The ball hit high off the centerfield wall — just missing a game-tying home run — and Indians centerfielder Marquis Grissom threw a strike to second that handily beat O’Neill to the bag. Using an extraordinary display of athletic quick thinking, O’Neill slid around the tag of shortstop Omar Vizquel and stretched out his hand to reach the far side of the base. When O’Neill stood up his face was bloodied from the slide, and despite O’Neill’s fervent objections Torre brought in a pinch-runner. Although the hit went for naught when Bernie Williams flew out to end the game, the sequence of O’Neill bludgeoning the pitch and somehow eluding Vizquel’s tag has become the enduring character portrait of the ferocity with which he played.

Like the rest of the Yankees, O’Neill was stung by the loss to a team they felt they should have beaten easily, and used this motivation to produce a record-setting 1998 season. With a .317 average and 24 home runs, O’Neill was a mainstay on the Yankees’ 114-win juggernaut. Heading into the 1999 season, the man whom Yankees owner George Steinbrenner often called a “warrior” owned a .317 career average as a Yankee, a mark bested only by Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Joe DiMaggio and Earle Combs.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.