Pedro Martinez Stats & Facts

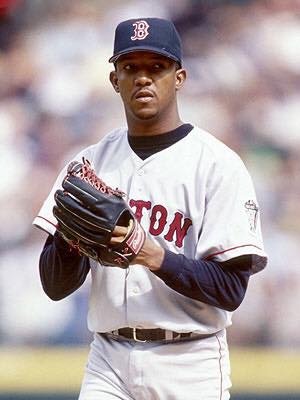

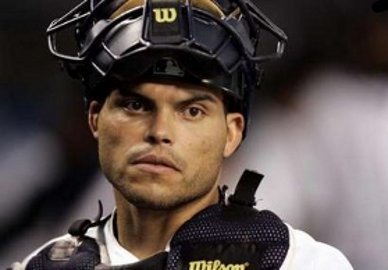

Pedro Martínez

Position: Pitcher

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

5-11, 170lb (180cm, 77kg)

Born: October 25, 1971 in Manoguayabo, Dominican Republic

Debut: September 24, 1992 (13,862nd in MLB history)

vs. CIN 2.0 IP, 2 H, 1 SO, 1 BB, 0 ER

Last Game: September 30, 2009

vs. HOU 4.0 IP, 6 H, 2 SO, 1 BB, 3 ER

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 2015. (Voted by BBWAA on 500/549 ballots)

View Pedro Martínez’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Pedro Jaime Martinez

Nicknames: Pedro el Grande or Petey

Twitter: @45PedroMartinez

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Notable Events and Chronology

Biography

“There has never been a pitcher in baseball history – not Walter Johnson, not Lefty Grove, not Sandy Koufax, not Tom Seaver, not Roger Clemens – who was more overwhelming than the young Pedro.“Joe Posnanski Sports Illustrated

Pitching almost exclusively during the offensive-minded period that came to be known as The Steroid Era, Pedro Martinez dominated opposing batters when he was at his peak as few hurlers ever have. The slender righthander captured one pitcher’s triple crown, led his league in ERA five times, topped his circuit in strikeouts and winning percentage three times each, and typically compiled an earned run average almost two runs per-game below the league norm. Over a seven-year stretch from 1997 to 2003, Martinez posted an overall record of 118-36, for a remarkable .766 winning percentage. He also compiled an ERA below 2.50 in six of those seasons, twice allowing the opposition fewer than two earned runs per nine innings. Martinez won three Cy Young Awards, finished second in the balloting two other times, and was named his league’s Pitcher of the Year by The Sporting News on three separate occasions. Formulas used by sabermetricians to calculate the effectiveness of players based on different variables have Martinez ranked as one of the two or three greatest pitchers in baseball history.

Biography

Born in Manoguayabo, Dominican Republic on October 25, 1971, Pedro Jaime Martinez came from humble beginnings. Like most houses in Manoguayabo, a small town 30 minutes outside the capital city of his homeland, the Martinez home had dirt floors and a tin roof. Pedro’s father, Paolino, worked as a janitor, while his mother, Leopoldina, did laundry for other families in town. One of six children, Pedro grew up in a house in which the three bedrooms were formed by sheets hung from wires.

Despite their limited means, the Martinez children were relatively happy, that is, until their parents divorced when Pedro was eight years old. The family unit might well have crumbled had it not been for Ramon, the eldest of the Martinez children. Accepting the role of the new head of the household, Ramon became a hero to his younger siblings, helping to support his family by pitching in games around Santo Domingo by the time he turned 15. The eldest Martinez brother eventually signed with the Los Angeles Dodgers, who subsequently sent him to their academy in the Dominican Republic.

The fact that Ramon and Pedro both ended up pitching in the major leagues was very much a matter of heredity. Their father, a former teammate of Felipe and Matty Alou, had been one of the most respected pitchers on the island during the 1950s. An outstanding sinkerball pitcher, he possessed tremendous strength and stamina, occasionally pitching two games in one day. The Alous maintained that Paolino could have been a solid major leaguer, but he failed to appear for a scheduled tryout with the San Franciso Giants because he didn’t have enough money to purchase a pair of cleats.

Following in the footsteps of his father and older brother, Pedro chose to pursue a career in major league baseball as well, signing with the Dodgers as an amateur free agent at the age of 16, in 1988. Despite initial concerns about his lack of size (he began his pro career weighing only 135 pounds), Martinez accelerated through the Los Angeles farm system, excelling against all levels of competition. Opponents marveled at the smooth, compact motion and tremendous arm speed he generated with his small frame. The key was the torque Martinez produced as he twisted his upper body at the waist.

Before long, Martinez earned a promotion to Albuquerque, where he spent the 1992 campaign. The Dodgers called him up in late September, and the 20-year-old righthander made two appearances for the team during the season’s final week.

Martinez pitched well in spring training the following year to earn a spot on the Los Angeles roster. He then established himself as the team’s set-up man over the course of the season, performing brilliantly by compiling a record of 10-5, pitching to a 2.61 ERA, and striking out 119 batters in 107 innings of work, while allowing only 76 base hits. Nevertheless, Martinez remained determined to join his older brother Ramon in the Dodgers starting rotation, a desire he expressed to Tommy Lasorda. The Los Angeles manager, though, questioned the ability of the 5’10”, 175-pound hurler to hold up under the rigors of a 162-game schedule, leading to the trading of Martinez to the Montreal Expos for standout second baseman Delino DeShields prior to the start of the 1994 campaign.

Martinez gradually developed into one of the National League’s finest starting pitchers in Montreal. He showed early promise by throwing a perfect nine innings against San Diego on June 3, 1995, before finally surrendering a hit in the bottom of the 10th inning during a 1-0 Expo victory. Martinez posted a combined 38-25 record in Montreal from 1994 to 1996, before having his breakout year in 1997. He finished 17-8 for a mediocre Expos team, struck out 305 batters, and led the National League with a 1.90 ERA and 13 complete games, en route to earning his first Cy Young Award. Martinez’s 305 strikeouts and 1.90 earned run average made him the first righthanded pitcher since Walter Johnson in 1912 to accumulate as many as 300 strikeouts while allowing the opposition less than two runs per nine innings.

With free agency looming for Martinez, the Expos traded the star pitcher to the Boston Red Sox for pitchers Carl Pavano and Tony Armas, Jr. in November of 1997. Martinez signed a six-year, $75 million contract with Boston shortly thereafter, making him the highest paid pitcher in the history of the game at the time. Demonstrating that he was well worth the investment, Martinez went 19-7 for the Red Sox in 1998, struck out 251 batters, and posted a 2.89 ERA.

Martinez reached his zenith the following year, compiling one of the greatest seaons for a pitcher in baseball history. In addition to leading all American League hurlers with a record of 23-4, 313 strikeouts, and a 2.07 ERA, he allowed only 160 hits and 37 walks in 213 innings of work. Martinez performed so brilliantly that his 2.07 ERA was almost three runs per-game lower than the league average. New York’s David Cone placed a distant second to Martinez in that category, with a mark of 3.44. The Boston righthander ended up winning the Cy Young Award unanimously and finishing a close second in the league MVP voting.

While Martinez pitched magnificently throughout the entire 1999 campaign, four games in particular stand out as examples of the level of dominance he attained over the course of the season.

At the annual All-Star Game played before a packed house at Fenway Park, Martinez thrilled the hometown fans by striking out Barry Larkin, Larry Walker, Sammy Sosa, and Mark McGwire to start the contest. He also fanned Jeff Bagwell later in the second inning, thereby whiffing five of the six men he faced, en route to earning All-Star MVP honors.

Facing the Yankees in the Bronx on September 10th, Martinez dominated the eventual world champions during a 3-1 Red Sox victory. The Boston righthander allowed only a home run by New York’s Chili Davis during an overpowering 17-strikeout, one-hit performance.

A few weeks later, Martinez strained his back while pitching against the Cleveland Indians in Game One of the Division Series. Martinez left the contest with the Red Sox holding a 2-0 lead. However, Cleveland mounted a comeback against the Boston bullpen, eventually winning the game 3-2. The Indians also came out on top in Game Two, before the Red Sox rallied to win the next two contests, thereby tying the Series at two games apiece.

With Martinez’s back still hurting, Boston started Bret Saberhagen in the decisive fifth game in Cleveland. The contest soon evolved into a slugfest, with the Indians holding an 8-7 lead in the fourth inning. Red Sox manager Jimy Williams turned to Martinez in desperation, hoping his ailing righthander might stem the tide of the Cleveland onslaught. Unable to throw either his fastball or his changeup with any consistency, Martinez changed speeds and mixed his pitches brilliantly, baffling Cleveland’s lineup over six no-hit innings. He finished the game with eight strikeouts, and the Red Sox advanced to the ALCS by scoring five more times to win the contest, 12-8.

Martinez had yet one more great effort left in him. He allowed just two hits and struck out 12 in seven shutout innings against Roger Clemens and New York during Boston’s 13-1 Game Three mauling of the eventual world champions in the ALCS. The loss turned out to be the Yankees’ only one of the 1999 postseason.

The ability of Martinez to excel in such pressure situations speaks to the depth of his competitive spirit and willingness to perform under the spotlight. Former Expos GM Dan Duquette said of Martinez, “He is a fearless competitor who knows how to perform on the big stage, and has terrific charisma.” Mo Vaughn, who played behind Martinez in Boston during the late-1990s, suggested, “He just loves to pitch in front of a packed house, with everyone standing, watching him work.”

Among the other qualities that helped make Martinez so devastating were his wide arsenal of pitches and his ability to intimidate opposing hitters. Blessed with an outstanding fastball, cutter, curveball, and circle changeup, Martinez had the ability to throw any pitch in any situation. Furthermore, opposing batters often claimed they had a difficult time picking up the ball after Martinez released it from his three-quarter delivery.

When he was at his peak, Martinez consistently reached 95-97 mph on the radar gun with his fastball, prompting former Montreal Expo teammate Larry Walker to comment, “He’s so tiny. And I don’t know where he gets that speed from. That velocity is amazing.”

The combination of his tremendous velocity and his devastating changeup made Martinez practically unhittable. Randy Johnson noted, “He’s the first person I’ve ever seen with an above-average fastball and an above-average changeup.”

Making Martinez an even more imposing figure on the mound was the reputation he developed early in his career as a “headhunter.” Martinez never hesitated to let the opposing batter know the inside part of the plate belonged to him – a message he delivered frequently and effectively through the years. Jason Giambi suggested, “If you lean over the plate, he’ll stick one up your nose.”

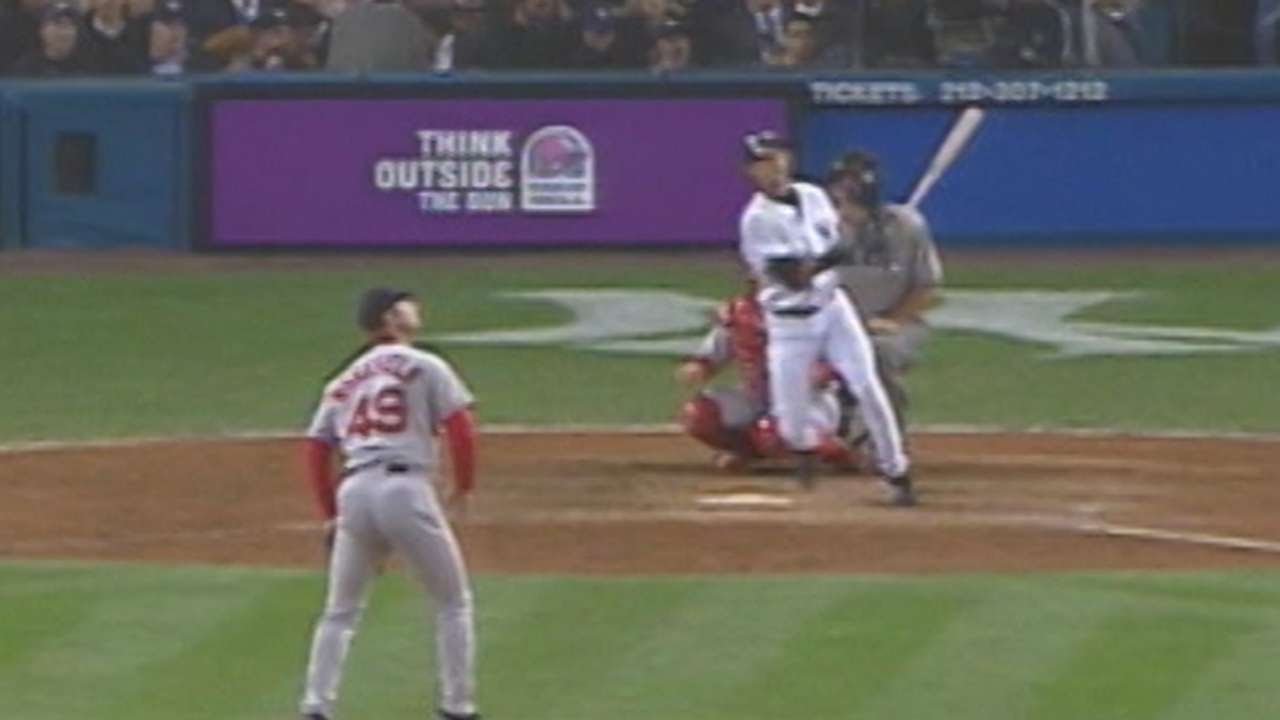

Manager Lou Piniella claimed, “Some people are a little afraid of Pedro, and that helps him.” Martinez’s tendency to throw at opposing hitters precipitated numerous bench-clearing incidents through the years, the most famous of which occurred during Game Three of the 2003 ALCS against the New York Yankees. After surrendering a home run to the previous batter, Martinez plunked Yankee outfielder Karim Garcia in the middle of the back with a pitch. After Garcia voiced his objection to the Red Sox righthander, words were exchanged between both benches. New York catcher Jorge Posada yelled a few choice words to Martinez from the Yankee dugout, to which Martinez responded by pointing to his head. Although Martinez later suggested he meant to tell Posada to think rationally, the Yankee receiver interpreted the gesture to mean “I’ll hit you in the head.” Both benches emptied and, in the ensuing fray, an angry Don Zimmer lunged at Martinez. The Red Sox hurler then threw the 72-year-old Yankee bench coach to the ground, an action that subsequently drew a great deal of criticism from the media. The above fracas was just one of many controversies in which Martinez became embroiled during his time in Boston. Virtually all of those highly-publicized incidents involved the Yankees On one occasion, an annoyed Martinez commented on the Red Sox – Yankees rivalry: “I’m starting to hate talking about the Yankees. The questions are so stupid. They’re wasting my time. It’s getting kind of old … I don’t believe in damn curses. Wake up the damn Bambino and have me face him. Maybe I’ll drill him in the ass, pardon me the word.”

After a Red Sox loss to the Yankees late in the 2004 season, Martinez remarked in a press conference, “They beat me. They’re that good right now. They’re that hot. I just tip my hat and call the Yankees my daddy.” The New York media publicized the quote heavily, and whenever Martinez pitched at Yankee Stadium during the 2004 ALCS, fans chanted “Who’s Your Daddy?”

Through all the controversies, though, Martinez remained a truly great pitcher. After dominating American League hitters throughout the 1999 campaign, he had another remarkable year in 2000. In addition to finishing 18-6, he led the A.L. with 284 strikeouts, a 1.74 ERA, and four shutouts, en route to capturing his third Cy Young Award. Martinez’s 1.74 ERA was less than half the mark posted by league runnerup Roger Clemens (3.70). He also allowed only 128 hits and 32 walks in 217 innings of work.

Martinez started off the following season extremely well, but ended up spending much of the year on the disabled list with a rotator cuff injury. Healthy again in 2002, Martinez finished 20-4, with a league-leading 239 strikeouts and 2.26 ERA. Although Martinez continued to take the ball every fifth day for the Red Sox in each of the next two seasons, concerns about his surgically repaired shoulder caused Boston management to place him on a strict pitch-count. He rarely threw more than 100 pitches or went more than seven innings in either 2003 or 2004. Yet, he remained one of the league’s most effective pitchers, striking out more than 200 batters both seasons, compiling a combined record of 30-13, and leading the A.L. with a 2.22 ERA in 2003. Martinez didn’t fare particularly well in either of his two starts against New York in the 2004 ALCS, but he shared in the joy of his teammates when they overcame a three-games-to-none deficit to defeat a stunned Yankee squad and capture the A.L. pennant. Martinez then threw seven shutout innings against St. Louis in his lone start in the World Series, as the Red Sox ended 86 years of futility by sweeping the Cardinals in four straight games in the Fall Classic.

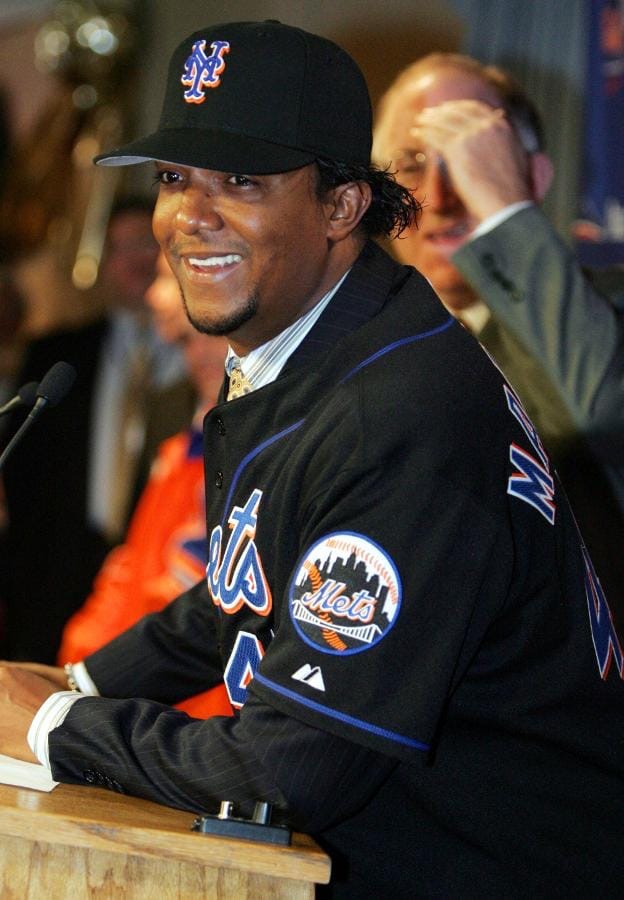

After becoming a free agent at the end of the year, Martinez reached an agreement with the New York Mets to return to the National League. He had a solid first year in New York, finishing 15-8 with a 2.82 ERA, and bringing a level of respectability to the struggling franchise. Tom Glavine, another member of the Mets’ starting rotation, provided insight into his new teammate’s makeup when he said, “Pedro’s a great competitor. He stares at hitters and pumps his fist when he pitches, but that’s all part of his competitive nature. After the game, he’s back to being humble. He’s always respectful of his opponents.”

Meanwhile, newspaper columnist Filip Bondy described the joy he derived out of watching Martinez continue to thwart opposing hitters, even though he no longer possessed the same overpowering fastball he had earlier in his career: “It is much more fun now to watch Pedro Martinez pitch than ever before. Minus the gross weaponry of power, we see only the high art form… We watch the brain and arm in harmonic convergence, disguising 85-mph fastballs as something far more fanciful than their velocity and arc… the radar gun never approaches 90. An 81-mph slider… an 83-mph fastball… a 76-mph changeup. These baseballs might not be pulled over for speeding on the Turnpike… If it is at all a struggle for Martinez adjusting to his own mortality, you would never know it from the fun this man has around a baseball park.”

However, injuries and advancing age limited Martinez to a total of only 48 starts the next three seasons, prompting the Mets to allow the hurler to leave via free agency at the conclusion of the 2008 campaign. After sitting out the first half of the 2009 season, Martinez joined the Philadelphia Phillies for the pennant-push, helping his new team repeat as N.L. champions by going 5-1 down the stretch. He didn’t officially retire at the end of the year, but, since no team has yet to offer him a contract, it appears that Martinez’s playing days may well be over. If so, he ended his career with a record of 219-100, a 2.93 ERA, and 3,154 strikeouts in 2,827 innings pitched. His .687 winning percentage places him second only to Whitey Ford among all pitchers with at least 200 victories.

Joe Posnanski once wrote in Sports Illustrated, “There has never been a pitcher in baseball history – not Walter Johnson, not Lefty Grove, not Sandy Koufax, not Tom Seaver, not Roger Clemens – who was more overwhelming than the young Pedro.”