Roberto Alomar Stats & Facts

Roberto Alomar

Position: Second Baseman

Bats: Both • Throws: Right

6-0, 184lb (183cm, 83kg)

Born: February 5, 1968 in Ponce, Puerto Rico

High School: Luis Munoz Rivera (Salinas, Puerto Rico)

Debut: April 22, 1988 (13,071st in MLB history)

vs. HOU 4 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 5, 2004

vs. SEA 2 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

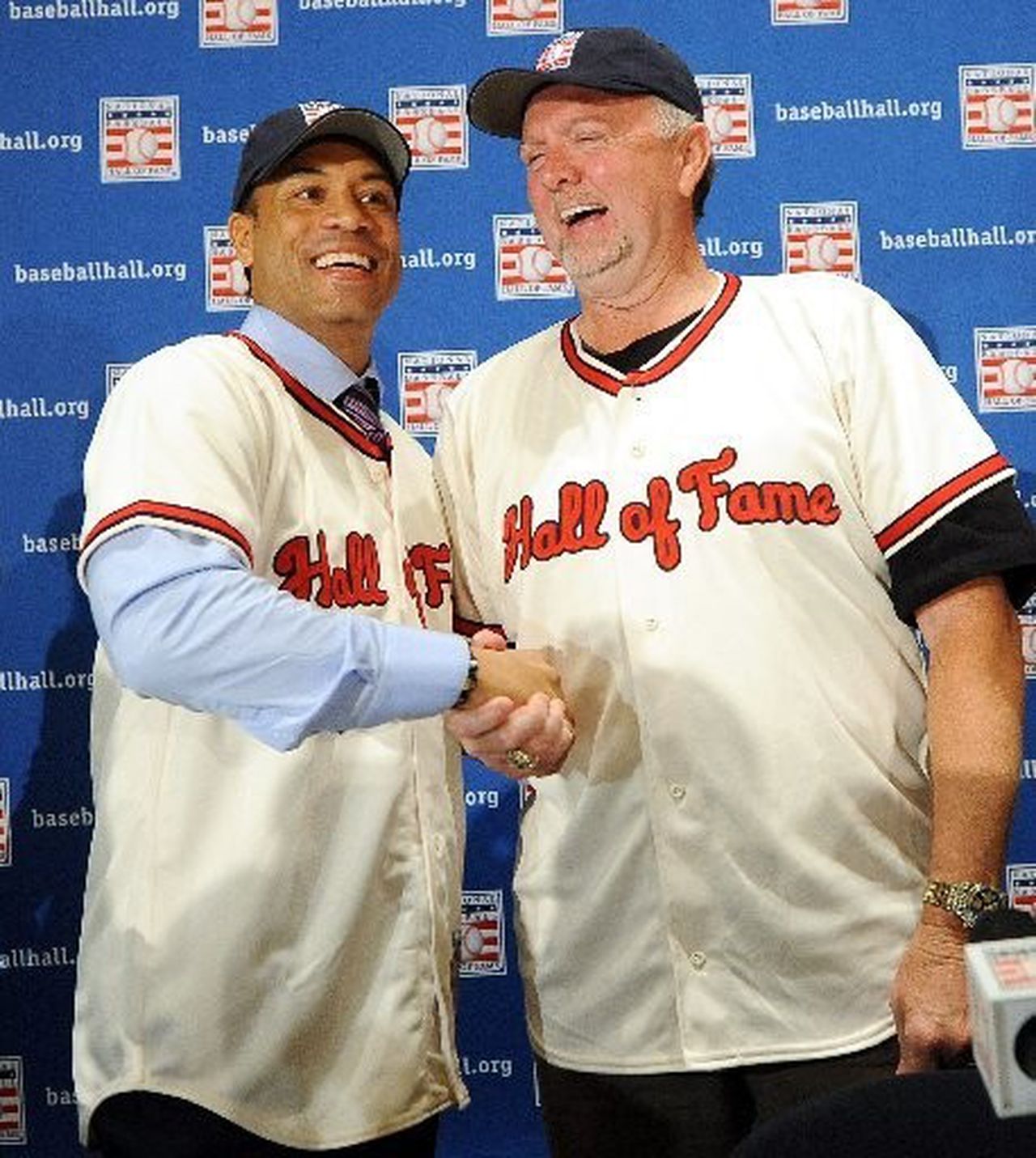

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 2011. (Voted by BBWAA on 523/581 ballots)

View Roberto Alomar’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Roberto Alomar

Pronunciation: \AL-loh-mar\

Twitter: @Robbiealomar

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

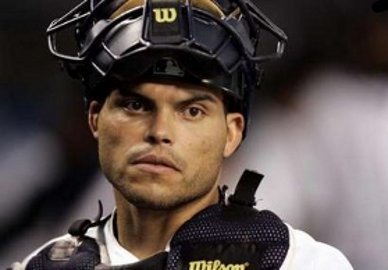

Relatives: Brother of Sandy Alomar; Son of Sandy Alomar

Notable Events and Chronology

Biography

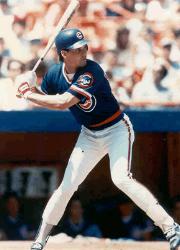

One of the finest all-around players of his generation, Roberto Alomar excelled in every aspect of the game. An outstanding hitter, the switch-hitting second baseman compiled a lifetime .300 batting average, surpassing the .320-mark five times during his career. He also topped 20 homers three times, 100 runs batted in twice, and 100 runs scored on six separate occasions. An exceptional baserunner, Alomar stole more than 40 bases four times, en route to swiping 474 bags and compiling an excellent stolen base success rate of 80 percent during his career. Perhaps Alomar’s greatest strength, though, lay in his defense. Blessed with superb range, sure hands, a strong throwing arm, and the quickness of a gazelle, Alomar was among the greatest fielding second basemen of all time. The winner of ten Gold Gloves, Alomar’s career fielding percentage of .984 is the highest of any player at his position in American League history. Alomar’s unique combination of skills not only made him one of the finest all-around players of his time, but, also, one of the premier second basemen ever to play the game.

Born in Ponce, Puerto Rico on February 5, 1968, Roberto Velazquez Alomar had baseball in his blood. As the son of former major league infielder Sandy Alomar, and the younger brother of big league receiver Sandy Jr., Roberto was exposed to the game at an early age. After growing up in Salinas, Puerto Rico, where he attended Luis Munoz Rivera High School, Alomar signed an amateur free agent contract with the San Diego Padres as a 17-year-old in 1985. He spent the next three years in San Diego’s minor league system, winning the California League batting championship in 1986 with a mark of .346. He joined the Padres in 1988, quickly winning the team’s starting second base job, while playing alongside his older brother and performing under the watchful eye of his father, who served the team as a coach. Alomar batted just .266 as a rookie, but he displayed outstanding potential, scoring 84 runs and stealing 24 bases in 30 attempts. He also exhibited outstanding range in the field, even though his 16 errors were the second most committed by any National League second baseman.

Alomar continued to perform somewhat erratically in the field in his second year in the league, committing an N.L. leading 28 miscues at second base. Nevertheless, the circuit’s youngest starting player developed into a solid offensive performer, batting .295, scoring 82 runs, and stealing 42 bases. Alomar had another solid offensive season in 1990, but, more importantly, he displayed greater consistency in the field, committing a total of 17 errors, including only six during the season’s second half. The young second baseman’s improved play earned him the first of 12 consecutive nominations to the All-Star Team.

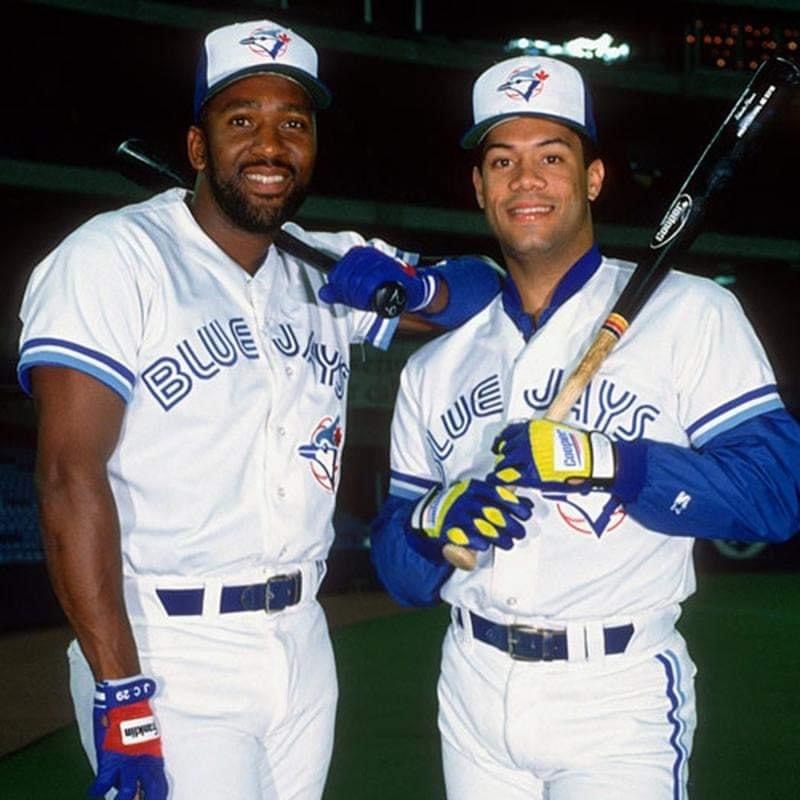

Alomar’s rapid development made him an extremely marketable commodity, enabling the Padres to trade him and teammate Joe Carter to the Toronto Blue Jays at the conclusion of the 1990 campaign for shortstop Tony Fernandez and slugging first baseman Fred McGriff. Although McGriff had some good years for San Diego, the deal turned out to be a steal for the Blue Jays, providing them with much of the core of their back-to-back championship teams of 1992 and 1993. Alomar batted .295, stole 53 bases, and won the first of his six straight Gold Gloves in his first season in Toronto. Although the Blue Jays subsequently came up short against Minnesota in the ALCS, Alomar batted a lusty .474 during the five-game playoff series.

Alomar established himself as one of the American League’s most formidable players the following year. In addition to committing only five errors in the field, he batted .310, compiled a .405 on-base percentage, scored 105 runs, and stole 49 bases. He then helped lead the Blue Jays to the world championship by capturing ALCS MVP honors. Not only did Alomar hit two home runs, drive in four runs, and bat .423 against Oakland during the Series, but he helped clinch the victory by homering against A’s relief ace Dennis Eckersley.

Alomar followed up his outstanding 1992 performance with another exceptional 1993 campaign. After establishing new career highs with 17 home runs, 93 runs batted in, 109 runs scored, 55 stolen bases, and a .326 batting average during the regular season, he excelled during the playoffs and World Series. Alomar batted .292 against Chicago in the ALCS, then helped lead the Blue Jays to their second straight world championship by hitting .480 and knocking in six runs against Philadelphia in the Fall Classic.

A broken leg suffered while playing winter ball in Puerto Rico hobbled Alomar in the spring of 1994, leading to a subpar season by the second baseman. Although Alomar batted .306 during the strike-shortened campaign, he knocked in only 38 runs and stole just 19 bases. Various injuries caused Alomar to miss a month of the following season, one in which he batted .300 and stole 30 bases, despite scoring only 71 runs – the lowest total of his career to that point. Nevertheless, Alomar had a magnificent year in the field, committing just four errors in 643 total chances, en route to compiling a career-high .994 fielding average and establishing new records for American League second basemen for consecutive errorless games (104) and consecutive errorless chances (482).

Alomar’s brilliance in the field was exemplified not only by his extremely consistent play, but also by his great range and tremendous athleticism. He had the ability to turn apparent base hits into outs in any number of ways. His quickness enabled him to go deep into the hole, dive for the ball, rise to his feet in the blink of an eye, whirl, and toss out the incredulous batter at first base. Alomar’s great range and powerful throwing arm also permitted him to field balls behind second base and fire laser beams to first, depriving many an opposing batter of an apparent hit.

After winning his fifth consecutive Gold Glove Award with the Blue Jays in 1995, Alomar signed a lucrative free-agent deal with Baltimore prior to the start of the 1996 campaign. He had a fabulous first year in Baltimore, teaming up with Cal Ripken Jr. to give the Orioles the league’s best double play combination. In addition to winning another Gold Glove for his stellar play in the field, Alomar established new career highs with 22 home runs, 94 runs batted in, 132 runs scored, 43 doubles, a .328 batting average, a .411 on-base percentage, and a .527 slugging percentage. Yet, Alomar’s brilliant year was marred by an ugly late-season incident that permanently damaged his previously spotless reputation.

During a September 27th game against the Blue Jays, Alomar got into a heated exchange with home plate umpire John Hirschbeck over a called third strike. Towards the end of the argument, Alomar showed his disdain for Hirschbeck by spitting in his face. The Baltimore second baseman later attempted to defend his actions by saying that Hirschbeck had uttered a racial slur during the altercation, and that the umpire had become “real bitter” since his son died of a rare brain disease (ALD) in 1993. Upon hearing this public disclosure of his personal life, Hirschbeck had to be physically restrained from confronting Alomar in the players’ locker room.

Alomar’s unsavory actions resulted in a five-game suspension at the start of the 1997 season. He attempted to restore his tarnished image by donating $50,000 to ALD research, while also burying the hatchet with Hirschbeck prior to the start of an April 22, 1997 contest by standing at home plate and shaking hands with the umpire in front of the crowd. Addressing the issue upon his retirement, Alomar stated, “That, to me, is over and done. It happened over nine years ago. We are now great friends. We have done some things with charity. God put us maybe in this situation for something. But I think people who know me, people who have had the chance to be with me on the same team, know what kind of person I am. Anything I ever did wrong, I would confront it and now it is okay.”

Despite Alomar’s attempts to smooth things over with the fans and the media, his popularity throughout the league waned. Booed vociferously by A.L. fans everywhere, Alomar nonetheless posted a .333 batting average in 1997. However, he appeared in only 112 games for Baltimore after hurting his left shoulder during an at-bat against the Indians on May 31. The injury, which required surgery during the offseason, forced Alomar to bat only left-handed the remainder of the season.

Alomar never again felt comfortable in Baltimore, and he appeared to be badly in need of a change in scenery after batting just .282 and driving in only 56 runs in 1998. While Alomar blamed his decreased offensive productivity on nagging injuries, team owner Peter Angelos openly speculated that his second baseman’s diminishing returns may well have been the result of the fallout from the Hirschbeck controversy. Meanwhile, Baltimore fans complained about what they perceived to be a lack of effort at times from the All-Star second sacker.

After becoming a free agent at season’s end, Alomar signed on with the Cleveland Indians, for whom his older brother Sandy Jr. also played. Inspired by the change in his surroundings, Alomar put together arguably the finest all-around season of his career. In addition to earning his eighth Gold Glove by making only six errors in the field all year, he batted .323, stole 37 bases, and established new career highs with 24 home runs, 120 runs batted in, a .422 on-base percentage, and a league-leading 138 runs scored. Alomar’s exceptional performance earned him a third-place finish in the league MVP voting.

Following another outstanding season in 2000, Alomar finished fourth in the MVP balloting in 2001, when he batted a career-best .336, hit 20 homers, knocked in 100 runs, and scored 113 others. However, the 2001 campaign turned out to be Alomar’s last big year. Traded to the New York Mets for three players prior to the start of the ensuing season, Alomar seemed unable to perform under the close scrutiny of the New York media and the glare of the big city’s spotlight. He slumped badly, hitting just .266 and displaying little passion for the game, either in the field or on the basepaths. After Alomar started off the 2003 campaign in similar fashion, the Mets elected to trade the second baseman to the Chicago White Sox, with whom his rather mediocre play continued. Alomar split 2004 between Chicago and Arizona, failing to regain his earlier form with either team, after missing two months with a broken right hand. He signed a one-year contract with Tampa Bay prior to the start of the 2005 campaign, but subsequently elected to retire during spring training after being plagued by back and vision troubles. Alomar ended his playing career with 210 home runs, 1,134 runs batted in, 1,508 runs scored, 2,724 hits, 474 stolen bases, a batting average of .300, and an on-base percentage of .371. In addition to winning ten Gold Gloves and appearing in 12 All-Star Games, Alomar finished in the top ten in the league MVP voting a total of five times.

Alomar’s credentials seemed to make him an odds-on favorite to gain induction to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. However, he fell eight votes short the first time his name appeared on the ballot in 2010, prompting widespread speculation that many members of the BBWAA have still not forgotten that unfortunate 1996 incident between Alomar and John Hirschbeck. In 2011, the BBWAA inducted Alomar by a 90% vote, one of the highest in history.