Sam Rice Stats & Facts

VINTAGE BASEBALL MEMORABILIA

Vintage Baseball Memorabilia

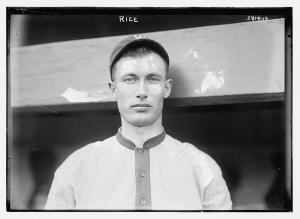

Sam Rice

Position: Rightfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Right

5-9, 150lb (175cm, 68kg)

Born: February 20, 1890 in Morocco, IN

Died: October 13, 1974 in Rossmoor, MD

Buried: Woodside Cemetery, Brinklow, MD

High School: Rhode Island Country HS (Rhode Island Country, IN)

Debut: August 7, 1915 (4,374th in major league history)

vs. CHW 1.2 IP, 1 H, 0 SO, 0 BB, 0 ER

Last Game: September 18, 1934

vs. WSH 5 AB, 3 H, 0 HR, 2 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1963. (Voted by Veteran’s Committee)

View Sam Rice’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Edgar Charles Rice

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1915

Sam Rice

Rogers Hornsby

Joe Judge

George Sisler

Dave Bancroft

Dazzy Vance

Charlie Jamieson

George Kelly

Baby Doll Jacobson

The Sam Rice Teammate Team

C: Muddy Ruel

1B: Joe Judge

2B: Buddy Myer

3B: Ossie Bluege

SS: Roger Peckinpaugh

LF: Goose Goslin

CF: Clyde Milan

RF: Sam West

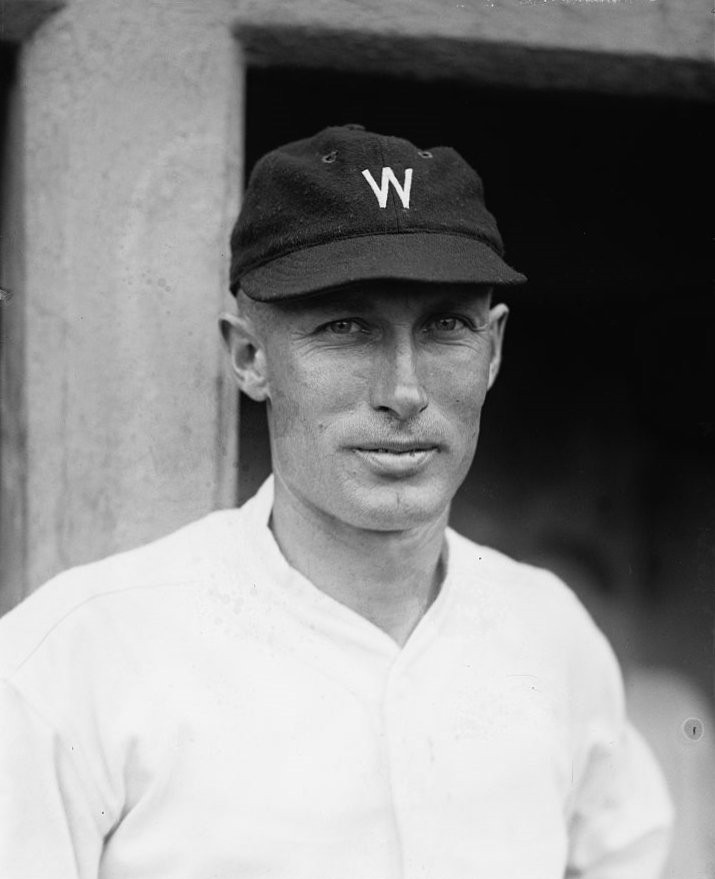

SP: Walter Johnson

SP: Tom Zachary

SP: Stan Coveleski

SP: Mel Harder

RP: Firpo Marberry

M: Bucky Harris

Notable Events and Chronology for Sam Rice Career

Biography

Thirteen hits from 3,000 is a lot more than Sam Rice could have been expected to accomplish considering his tragic pre-baseball life, the fact that he came up as a pitcher, and that he didn’t secure a full-time major league job until he was 26 years old. A quick outfielder with a great arm, Rice led the American League in hits twice and stolen bases once, while finishing in the top ten in batting eight times. On six occasions he collected at least 200 base hits, and he was an effective player well into his 40s. He was one of the most popular players in Washington Senators’ history, and one of the most respected men in baseball during his career. He was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1963.

Biography

Rice was born Edgar Charles Rice, in Morocco, Indiana, on February 20, 1890. Morocco was an industrial town, with a mill and a factory that produced textiles. Not much is known about Rice’s parents or siblings. When he was a young man, in his early 20s and just married, Rice left home to take a job several miles away. While he was gone, his entire family was killed by a tornado. Rice lost his wife and two children, and his father and mother, in addition to everything he owned, and his home. Following the tragedy, which was covered widely throughout the state, Rice left the area and joined the merchant marines for a few years, traveling the Great Lakes and playing semi-pro ball as he moved along. Later in life, after he was a ballplayer, he remarried, but did not tell his second wife about the disaster until a newspaper reporter revealed it in the 1950s. Rice’s first marriage and the loss of his children had been a dark secret he’d kept for decades.

On January 24, 1913, Rice enlisted in the U.S. Navy. On April 15, 1914, when President Woodrow Wilson ordered warships to Mexico to respond to an insurrection, Rice was a seaman aboard the battle ship USS New Hampshire. Rice saw action during the war, when the New Hampshire bombarded the city of Vera Cruz. Later, he told his daughter, that he had seen men falling on both sides of him during heavy fire. Back in the United States in August of 1914, Rice played baseball for semi-pro teams in Virginia while on leave. The owner of the Portsmouth team recognized Sam’s skill and bought his enlistment from the Navy for $800.

Rice played for the Portsmouth Truckers in 1914 and 1915, mostly as a pitcher. A southpaw, Rice had a strong arm, but also exhibited a flashy bat, hitting .304 in parts of two seasons. In July of 1915, the owner of the Portsmouth team tipped off Senators’ owner Clark Griffith that the Virginia League was about to fold. The owner was still in debt $600 to Griffith, and suggested that he take his “star pitcher” as payment for the loan, since the league was about to go belly-up. That’s how the Washington Senators acquired Sam Rice.

On August 7, 1915, Rice made his big league debut when Griffith inserted him as a relief pitcher. A month later, on September 7, Rice got his first big league start, pitching the second game of a doubleheader against the Athletics in Philadelphia. The Senators scored seven runs for Sam, as the lefty earned his first (and last) major league victory. The next season, Rice started in the Senators’ bullpen, but his batting skills made him Griffith’s first choice off the bench in a pinch. In late July, when he surrendered a double to light-hitting Hooks Dauss of Detroit, Rice tore the toe plate from his pitcher’s cleat and announced that he was through with pitching. For weeks, teammate Eddie Foster had been urging Rice to give up pitching and become an outfielder. Foster’s instincts proved prophetic, as Rice hit .299 that year, and followed with 14 .300 seasons before he retired 18 years later.

Playing mostly right field, Rice’s biggest defensive assets were his quick feet and his strong arm. He led the American League in assists once, and was among league leaders several times. His 454 putouts in 1920 were an AL record at the time, and he led the loop in that category twice. On the basepaths, Rice used his speed to swipe a league-best 63 bases in 1920, and he ranked in the top five in that category for eight straight years. Of his 34 career home runs, all but 13 of them were of the inside-the-park variety. He spent much of his career as a leadoff hitter, banging out singles, which were his specialty.

In 1924, Rice led the AL in hits, and the Senators won their first pennant, earning the right to face the New York Giants in the World Series. In a seven-game thriller, Rice hit .207 (6-for-29) with two stolen bases, as the Senators copped their only World Championship. The following season, Rice and the Senators repeated as AL champs, but lost the Series in seven games to Pittsburgh, despite Sam’s .364 average, 12 hits, five runs, and three RBI. In one of the most famous plays in World Series history, Rice fell into the stands in Game Three of the 1925 World Series, seemingly robbing Pirate Earl Smith of a home run. With he and the ball out of view in the crowded stands, the umpire could not tell if Rice had held on to the ball. Rice emerged with the ball safely in his glove and Smith was called out, prompting an argument by Pittsburgh. Rice was cryptic about the play, guarding the details of what happened in the stands as if he enjoyed the intrigue. When summoned by commissioner Landis to explain the play, Rice responded that he must have caught the ball “because the umpire said so.” That was good enough for Landis, but the debate raged for years.

In 1933, still with Washington, Rice made a pinch-hit appearance in the Fall Classic, collecting a hit to raise his career World Series average to .302 (19-for-63). By that time, Rice was the Senators’ fourth outfielder, and at the end of his career. In January of 1934, Washington released Rice, and a few weeks later he signed with Cleveland. At the age of 44, Rice hit .293 in 97 games for the Indians in 1934.

Though the left-handed hitting Rice never led the league in batting, he was a top-ten finisher eight times, with a career-high of .350 in 1925, when he banged out 227 hits. Rice reached the 200-hit mark six times, including 1930, when he was 40 years old. Keeping himself in great shape, Rice was one of the most productive players in baseball history after his 40th birthday, hitting .321 in 543 games after the age of 40. His career average was .321, on the strength of 2,987 hits. When Rice retired following the 1934 season, he didn’t realize the significance of the 13 hits he needed to reach the 3,000 mark. At that time, milestones such as 3,000 hits were rarely noted. In the 1940s, by the time he had the desire to collect the extra 13 hits, Rice was in his 50s.

After his playing career, Rice ran a chicken farm in Maryland, and later raised pigeons. He remained very active, well into his 80s, playing golf and working around his home. As late as the age of 83, Rice could shoot his age on the golf course. In 1963, he was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee, after Washington sportswriter Shirley Povich campaigned for him for years. In 1965, prompted by officials at the Hall of Fame, Rice penned a letter explaining the famous play in the 1924 Series. His instructions were to have the note opened upon his death. On October 13, 1974, Rice died at Rossmor, Maryland, at the age of 84. The letter, dated July 26, 1965, detailed the entire play and concluded that “at no time did I lose possession of the ball.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Strange Things that may only interest me

The fleet-footed Rice was dubbed “Man O’ War” after the famous racehorse of that name. Rice, who was born Edgar Charles Rice, earned the name “Sam” while in the minor leagues. A reporter wished to mention Rice in his report, but wasn’t sure what his first name was. He placed “Sam” in the text of his story as a placeholder, and never changed it. When the name “Sam Rice” emerged in the papers, it seemed so perfect, that it stuck. Rice himself liked the name much better than Edgar, and embraced it immediately.

Linked:

Rice and Goose Goslin were teammates for parts of 11 seasons on the Senators… Clyde Milan played alongside Rice in the Nats’ outfield for seven seasons… For six seasons Sam West joined Sam Rice in the Senators’ outfield… Willie Wilson eclipsed Rice’s mark for singles in a season… Rice and Joe Judge were roommates for several years.

Best Season, 1925

He had several seasons of similar value. In 1925 he batted .350 (career-high) with 227 hits (career-high), and 111 runs scored. He batted leadoff most of his career, but in ’25 he moved down to #2 and drove in 87 runs. His 182 singles were an AL-record until 1980.

Post-Season Appearances

1924 World Series

1925 World Series

1933 World Series

Description

“He was a lefthanded hitter who stood up straight, even with the plate and very close to it and he took a quick cut at the ball. His stance hardly varied from the time that Washington brought him up from Petersburg of the Virginia League in 1915, until he retired after the 1934 season. He seldom argued with umpires, went about his work quietly and was not considered colorful… He was a fastball hitter and liked to torment Lefty Grove in particular… [Posessed] a personality closely resembling that of Charley Gehringer.” — Lee Allen of the Sporting News

Post-Season Notes

In one of the most famous plays in World Series history, Rice fell into the stands in Game Three of the 1925 World Series, seemingly robbing Pirate Earl Smith of a home run. With he and the ball out of view in the crowded stands, the umpire could not tell if Rice had held on to the ball. Rice emerged with the ball safely in his glove and Smith was called out, prompting an argument by Pittsburgh. Rice was cryptic about the play, guarding the details of what happened in the stands as if he enjoyed the intrigue. Several years later, prompted by the Hall of Fame, Rice penned a letter explaining the incident, asking that it not be opened until after his death. In part, it read: “At no time did I lose possession of the ball.” Sam Rice had kept the secret of his most famous play a secret all those years.

Feats: In 1925, Rice set an American League record with 182 singles… On September 18-19, 1925, Rice collected nine hits in a row.

Milestones

Rice showed little interest in sticking around to collect the 13 hits he needed to reach 3,000 for his career, since such milestones were barely noted in those days.

Notes

Rice finished fourth in American League Most Valuable Player voting in 1926… Was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1963.

Hitting Streaks

31 games (1924)

31 games (1924)

29 games (1920)

29 games (1920)

28 games (1930)

28 games (1930)

Transactions

43-year old Rice was released by the Senators following the 1933 season, after having lost his starting job and hitting .294 in 73 games. On February 14, 1934, the Cleveland Indians signed him to a contract for the 1934 campaign. In his final major league season, Rice played in 97 games, hitting .293 and falling 13 hits shy of 3,000.

Data courtesy of Restrosheet.org

Sam Rice Day

On July 19, 1932, the Washington Senators held “Sam Rice Day” at Griffith Stadium. In his 18th season with the team, Rice was honored with several gifts in a pre-game ceremony. Three players: Herb Pennock of the Yankees, Eddie Rommel of the Athletics, and Milt Gaston of the White Sox, were in attendance to show their respect for the veteran outfielder. The visiting Detroit Tigers were represented by manager Bucky Harris, who had managed the Senators and Rice from 1924-1928. Rice was presented with $2,235.09, a new Studebaker automobile, an engraved “loving cup,” a silver service set, an electric clock, a wrist watch, a portrait painted by artist Frank Hall, and a set of golf clubs. President Herbert Hoover sent a letter of congratulations, which read in part: “You have given all of us who love baseball so much pleasure that you have richly earned the honor of a ‘Sam Rice Day’.” Rice, always humble, was brief in his pre-game speech, stating simply: “Thanks, folks. This is the greatest day in my baseball career.” In his first at-bat, Rice singled to left field and umpire Brick Owens retrieved the ball for Sam as a souvenir.

Man O’ War

Old Man O’ War, for many years

You’ve been a target for our cheers.

We’ve marveled at your boundless speed

Which won us games in time of need.

Afield you’ve thrilled us with your grace

We’ve smiled the while you set the pace.

Somehow you always seemed a cinch

To clock that apple in the pinch.

To play the game with loyla heart,

A splendid soldier, loyal, smart.

Now at the parting of the ways

We wish you many happy days.

And though we realize you’ve gone

Somehow we feel you’ll carry on.

Some other team with pennant dreams

May well include you in its schemes.

Old Man O’ War, you’ve played and won:

Yours was a race superbly run.

Written by Joe Holman upon Rice’s release by the Washington Senators, January 8, 1934.

Home Run Facts

21 of Sam Rice’s 34 career home runs were of the inside-the-park variety.

Hall of Fame Artifacts

When he was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1963, Sam Rice was far from overjoyed, but then again, Rice always had a different take on things. His reaction? “Oh it’s fine, but I can’t say I’m too thrilled about it. If it were a real Hall of Fame, you’d say Cobb, Speaker, Walter Johnson, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and a few others belonged and then you’d let your voice soften to a mere whisper.”

Replaced

In 1916 Rice (who had been signed as a pitcher), earned a spot in the outfield, replacing switch-hitting right fielder Danny Moeller. Moeller was a power hitter from Louisiana with decent speed. But he was a terrible outfielder, and his batting average rarely crept above the .250 mark. Moeller was traded in August to the Indians for outfielder Elmer Smith (who Rice also beat out of the starting job), and infielder Joe Leonard.

Replaced By

In 1932, Carl Reynolds nudged Rice out of the right field starting job in Washington. Reynolds was a power-hitting slugger with a career .322 batting average at that point. The Senators had acquired him in a five-player swap with the White Sox in December of 1931. In ’32, Reynolds hit his customary .300, but in cavernous Griffith Stadium his power was wasted and he hit just nine home runs. 42-year old Rice hit .323 in 288 at-bats. In December of 1932, Reynolds was traded in a six-player deal that netted outfielder Goose Goslin, among others. Goslin was inserted in right field and Rice was used as Washington’s #4 outfielder in 1933.

Best Strength as a Player

His throwing arm.

Largest Weakness as a Player

It’s hard to say with complete accuracy just how good an outfielder Rice was, but his fielding stats show that he frequently made miscues. His lifetime fielding percentage is league-average and his range factor (the number of balls he got to) is barely better than average. This would explain the Senators’ constantly searching for a center fielder so Rice could be placed in right field, where his limited range and his powerful throwing arm were better suited. Rice was fast — one of the fastest players in baseball during his prime — so his fielding stats may indicate poor judgment on fly balls or some other factor that has been lost to history.