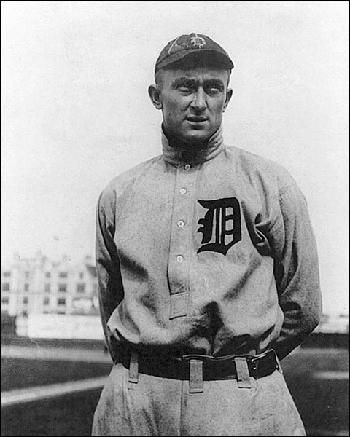

Ty Cobb Stats & Facts

Ty Cobb

Position: Centerfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Right

6-1, 175lb (185cm, 79kg)

Born: December 18, 1886 in Narrows, GA

Died: July 17, 1961 in Atlanta, GA

Buried: Rose Hill Cemetery, Royston, GA

High School: Franklin County HS (Royston, GA)

Debut: August 30, 1905 (2,755th in MLB history)

vs. NYY 3 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 11, 1928

vs. NYY 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

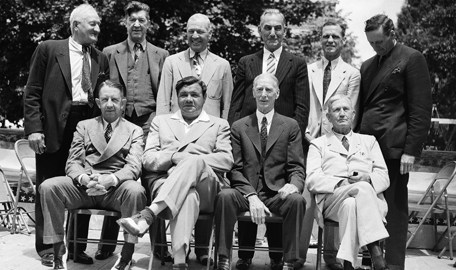

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1936. (Voted by BBWAA on 222/226 ballots)

Induction ceremony in Cooperstown held in 1939.

View Ty Cobb’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Tyrus Raymond Cobb

Nicknames: The Georgia Peach

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1905

Ty Cobb

Hal Chase

Mickey Doolan

Otto Knabe

Al Bridwell

Rube Oldring

Eddie Cicotte

Ed Reulbach

George Gibson

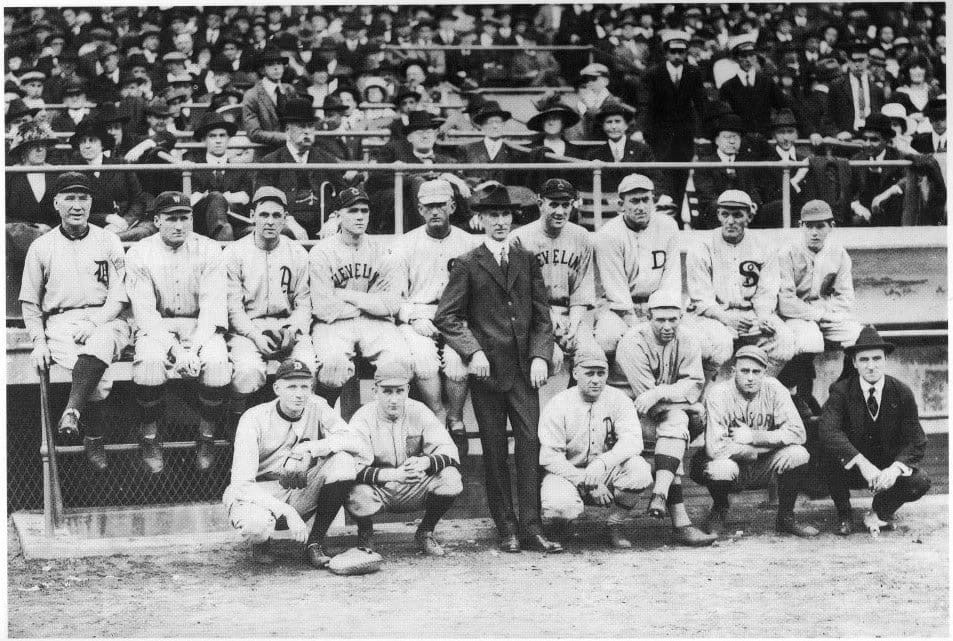

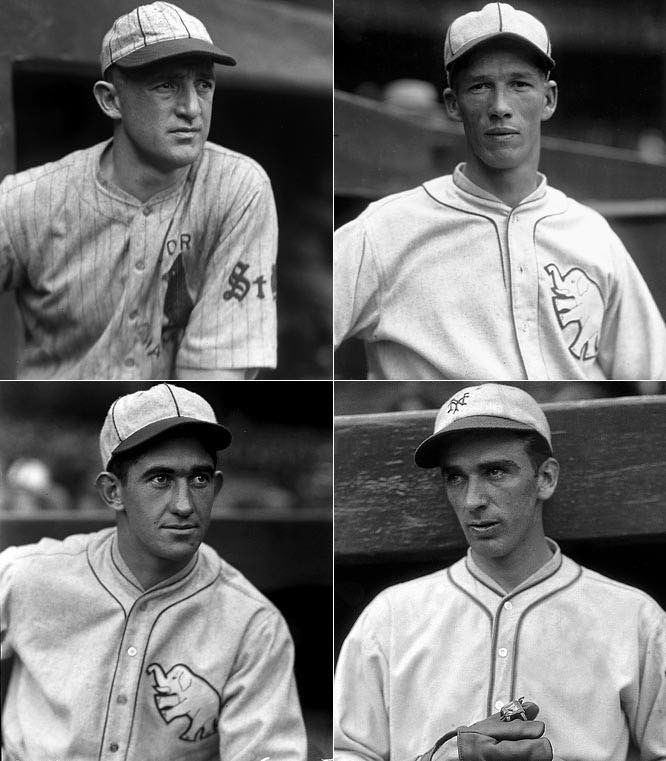

The Ty Cobb Teammate Team

C: Mickey Cochrane

1B: Lu Blue

2B: Charlie Gehringer

3B: Jimie Foxx

SS: Donie Bush

LF: Harry Heilmann

CF: Tris Speaker

RF: Sam Crawford

SP: George Mullin

SP: George Earnshaw

SP: Hooks Dauss

SP: Ed Killian

SP: Bill Donovan

RP: Lefty Grove

M: Hughey Jennings

Notable Events and Chronology for Ty Cobb Career

Biography

Tormented by personal demons that once drove him into a sanitarium, Ty Cobb played the game of baseball with an anger and contentiousness never manifested by any other player in the history of the sport. Cobb’s sense of purpose and will to excel made him the greatest player of his era. However, his combativeness and surly disposition also made him the most hated man in baseball for more than two decades.

Tyrus Raymond Cobb was born in Narrows, Georgia on December 18, 1886, the first of three children to Amanda Chitwood Cobb and William Herschel Cobb. He made his major league debut in centerfield for the Detroit Tigers at the age of 18 on August 30, 1905, just three weeks after his mother shot and killed his father in an apparent case of mistaken identity.

Cobb’s mother claimed at her subsequent murder trial that she was home alone late one evening when she heard strange noises emanating from the porch of her private home. Rushing to the window, she shot the intruder once in the stomach, and again in the face. The victim of the shooting turned out to be Cobb’s father, who it later surfaced intended to surprise his wife since he suspected her of infidelity. Cobb later attributed his ferocious style of play to the death of his domineering father, who told his son when he first elected to make baseball his chosen profession: “Don’t come home a failure.” Cobb explained his actions on the ballfield by saying, “I did it for my father. He never got to see me play…but I knew he was watching me, and I never let him down.”

Cobb struggled in his first year with the Tigers, batting just .240 in his 41 games with the team in 1905. However, he hit .316 over the first four months of the 1906 campaign, before finally succumbing to the enormous pressures that were thrust upon him at such an early age. With the weight of his father’s death and the subsequent murder trial of his mother already exacting a major toll on his psyche as the season progressed, the 19-year-old’s emotional strength was further tested by the brutal hazing he received at the hands of his Detroit teammates, who resented his arrogance and boastful nature. Cobb believed himself to be the most talented player in the game, and he let everyone else around him know exactly how he felt. He also considered anyone who disagreed with him to be his adversary, be it opponent or teammate. Feeling that they needed to keep the pugnacious youngster in his place, Cobb’s Tiger teammates took every possible opportunity to abuse him, both mentally and physically. One player was even assigned the task of “roughing him up” occasionally to keep him in line. No longer able to cope with the daily stress, Cobb was forced to spend the final six weeks of the season in a sanitarium. He later recalled that the treatment he received from his teammates during the early stages of his career turned him into “a snarling wildcat.”

Cobb described the war-like attitude he brought with him to the baseball diamond when he said, “Baseball is a red-blooded sport for red-blooded men. It’s no pink tea, and mollycoddles had better stay out. It’s a struggle for supremacy, a survival of the fittest.”

He added, “I had to fight all my life to survive. They were all against me, but I beat the bastards and left them in the ditch.”

Even though they resented their young teammate, the other members of the Tigers benefited greatly from the passion with which Cobb played the game when he returned to the team in 1907. Displaying an aggressive style of play that the Detroit Free Press once described as “daring to the point of dementia,” Cobb captured the first of three consecutive batting titles, leading the league with a .350 batting average. He also finished first with 119 runs batted in, 212 hits, 49 stolen bases, and a .468 slugging percentage, in leading Detroit to the first of three straight American League pennants. Cobb’s numbers slipped somewhat in 1908, but he still led the league with a .324 batting average, 108 runs batted in, 20 triples, 36 doubles, and 188 hits. If there still remained a doubt in anyone’s mind as to who was the game’s greatest player, Cobb removed it in 1909 by leading the league in virtually every major statistical category. In addition to capturing the triple crown by finishing first in home runs (9), runs batted in (107), and batting average (.377), Cobb topped the circuit with 116 runs scored, 216 hits, 76 stolen bases, a .431 on-base percentage, and a .517 slugging percentage.

The only blemishes on Cobb’s record during those three seasons were Detroit’s three World Series losses and The Georgia Peach’s personal failures in the Fall Classic. Cobb batted a combined .262 in his only three World Series appearances, with no home runs, nine runs batted in, and just seven runs scored.

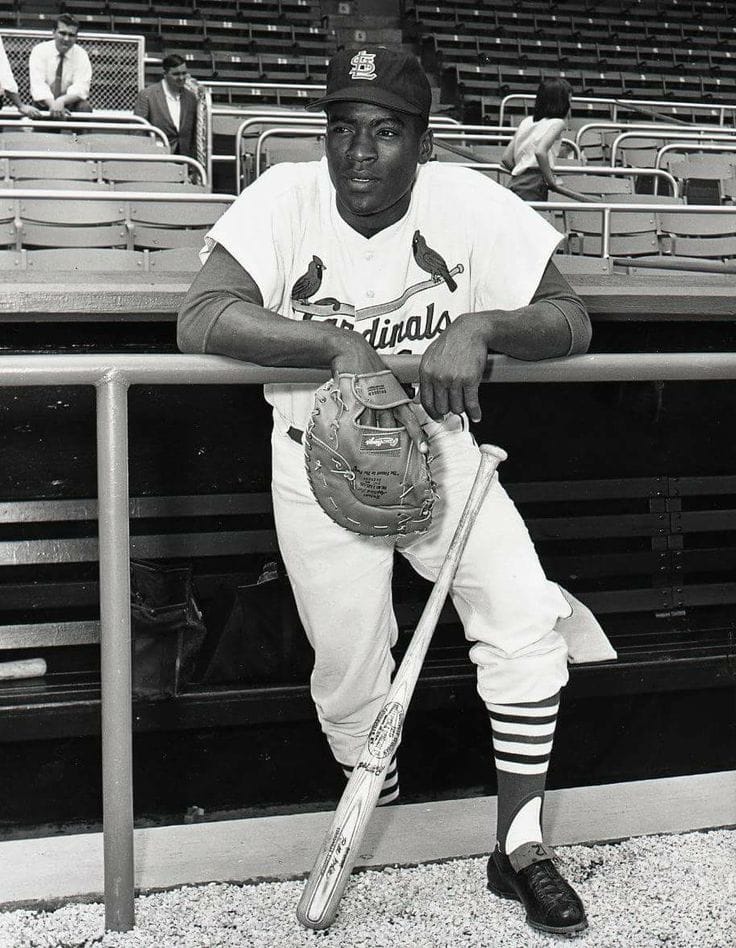

Cobb’s image was also tainted by his involvement in several unfortunate incidents. One such incident occurred in Spring Training in 1907. Well-known for his racial intolerance, Cobb complained to a black groundskeeper about the condition of the Tigers’ field in Augusta, Georgia. Not satisfield with the response he received, Cobb physically attacked the terrified man. He then began to choke the man’s wife when she attempted to intervene.

Another horrific episode took place on May 15, 1912, at Hilltop Park in Manhattan, during a game between Cobb’s Tigers and the New York Highlanders. A heckling fan had been shouting insults at Cobb from the stands the entire game. When he finally yelled at Cobb that he was a “half-nigger”, Cobb vaulted the fence and began stomping and kicking the fan with his spikes. When fans began yelling that the man was helpless because he had no hands, Cobb replied, “I don’t care if he doesn’t have any feet”, and kept kicking him until park police eventually pulled him away.

Still, in spite of his many transgressions, Cobb remained baseball’s greatest player.

After failing to win the batting title despite posting a mark of .383 in 1910, Cobb led the league in hitting in each of the next five seasons, compiling averages of .420, .409, .390, .368, and .369, respectively. He also led the league in runs scored, hits, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage three times each during that period, and he stole 96 bases in 1915 to establish a single-season record that stood for 47 years. Cobb had his greatest season, though, in 1911 when he topped the circuit with a career-high .420 batting average en route to earning A.L. MVP honors. He also led the league with 127 runs batted in, 147 runs scored, 248 hits, 83 stolen bases, 24 triples, 47 doubles, and a .621 slugging percentage. Cobb compiled a 40-game hitting streak at one point during the campaign.

Cobb continued to terrorize American League pitchers until he finally retired in 1928, at the age of 42. He was particularly effective in 1916, 1917, and 1922. In the first of those years, Cobb batted .371, compiled 201 hits, and led the league with 113 runs scored and 68 stolen bases. He led the league with a .383 batting average, 225 hits, 24 triples, 44 doubles, 55 stolen bases, and a .570 slugging percentage the following year. Then, at the age of 36 in 1922, Cobb batted .401. He also collected 211 hits, 16 triples, and 42 doubles.

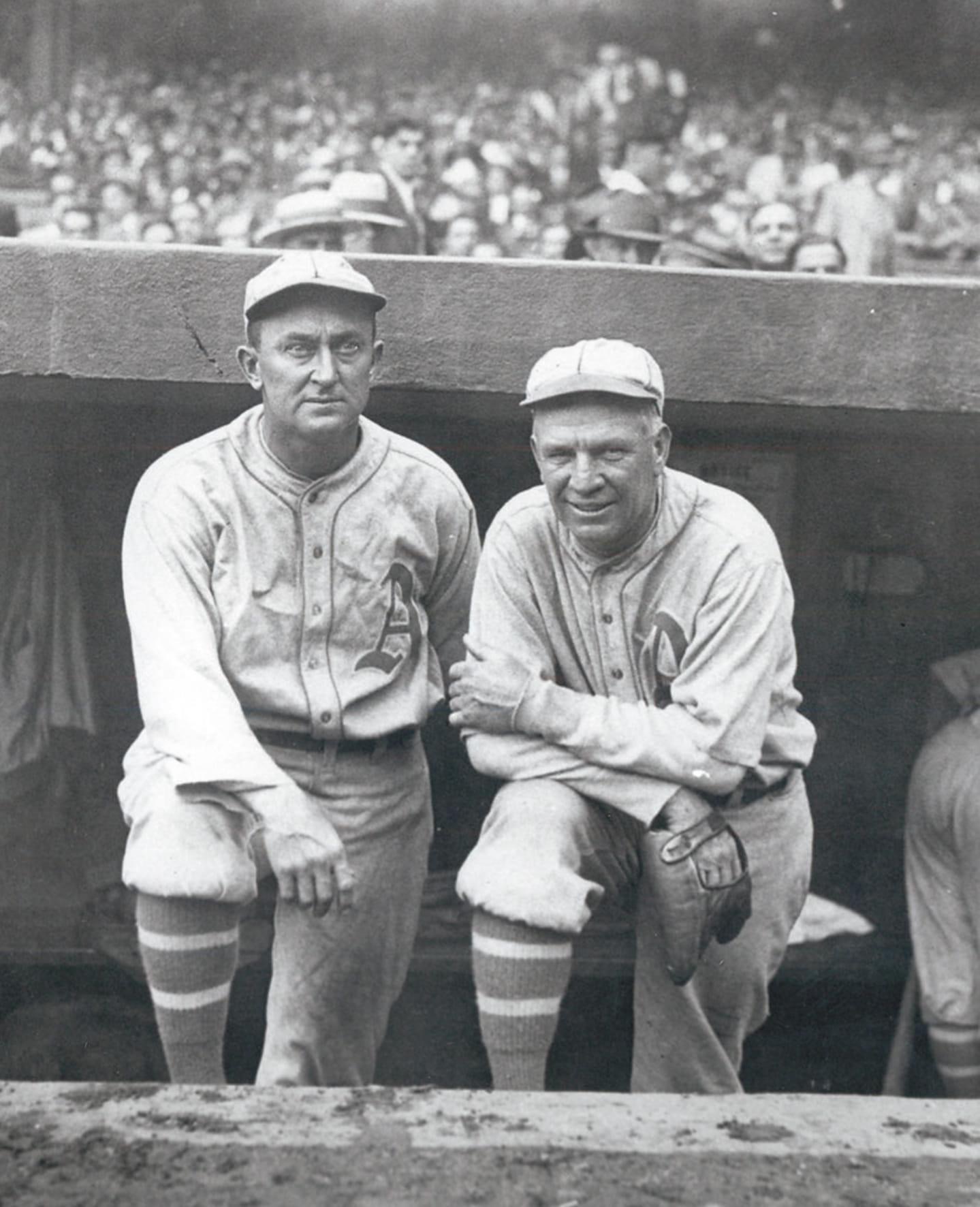

Cobb served as player-manager for the Tigers from 1921 to 1926, before spending his

final two years with Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics. When he retired at the conclusion of the 1928 season, Cobb was credited with holding 90 different major league records, many of which have since been broken. He was first on the all-time list with 1,937 runs batted in, 2,246 runs scored, and 4,189 hits. He was also near the top of the rankings with 891 stolen bases, 295 triples, and 724 doubles. Cobb still possesses the highest lifetime batting average in baseball history, with a mark of .367. He batted over .400 three times during his career, and he topped the .300-mark in 23 of his 24 seasons. He also surpassed 200 hits nine times, scored more than 100 runs 11 times, drove in more than 100 runs on seven separate occasions, topped 60 stolen bases six times, and surpassed 20 triples and 40 doubles four times each. Four times in his career, Cobb reached first base, then proceeded to steal second, third, and home in the same inning. He led the league in batting 11 times, hits and slugging percentage eight times each, stolen bases and on-base percentage six times each, runs scored five times, runs batted in and triples four times each, and doubles three times. In 1936, Cobb received the most votes of any player on the inaugural Baseball Hall of Fame ballot, receiving 222 out of a possible 226 votes.

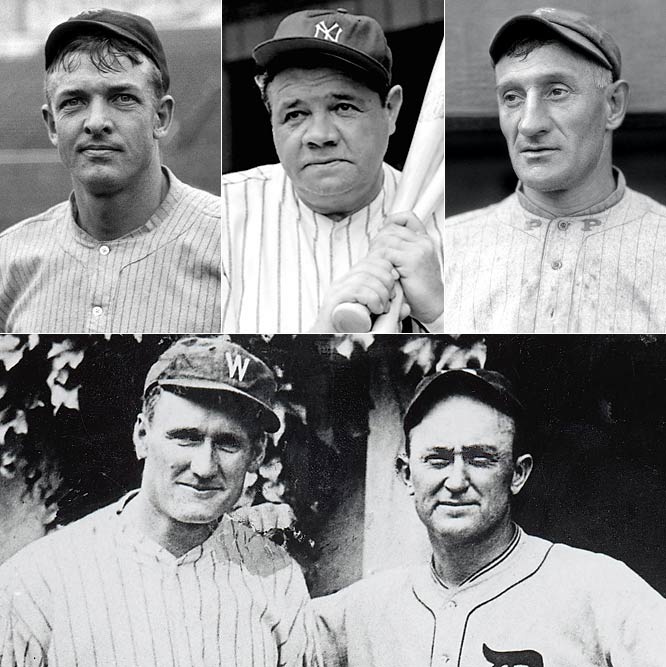

Shirley Povich, longtime sports columnist and reporter for the Washington Post, stated emphatically during a 1990s television interview, “If Babe Ruth isn’t the greatest baseball player who ever lived, then Ty Cobb is, by far!”

Ruth, himself, once praised his bitter rival for his playing ability when he said, “Cobb is a prick. But he sure can hit. God Almighty, that man can hit.”

Hall of Fame outfielder Tris Speaker, who competed against both Ruth and Cobb, had this to say: “The Babe was a great ballplayer, sure, but Cobb was even greater. Babe could knock your brains out, but Cobb would drive you crazy.”

Casey Stengel paid Cobb the ultimate tribute, saying, “I never saw anyone like Ty Cobb. No one even close to him. He was the greatest all time ballplayer. That guy was superhuman, amazing.”

George Sisler spent most of his career playing against Cobb as a member of the St. Louis Browns. The Hall of Fame first baseman said, “The greatness of Ty Cobb was something that had to be seen, and to see him was to remember him forever.”

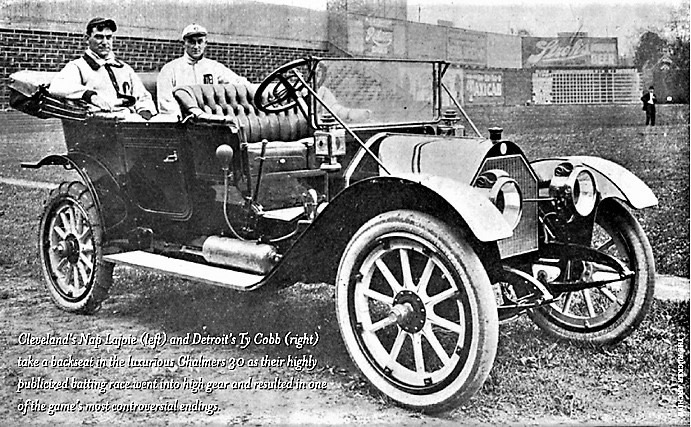

Yet, in spite of his greatness as a ballplayer, Cobb was disliked by virtually everyone in the sport. When Cleveland’s Napoleon Lajoie edged out Cobb for the American League batting title on the final day of the 1910 season, Tiger outfielder Sam Crawford displayed the disdain he felt towards his teammate by sending Lajoie a congratulatory telegram.

Crawford, who played alongside Cobb in the Detroit outfield for 13 seasons, provided some insight into his former teammate’s psyche when he suggested, “He (Cobb) was still fighting the Civil War, and as far as he was concerned, we were all damn Yankees. But who knows, if he hadn’t had that terrible persecution complex, he never would have been about the best ballplayer who ever lived.”

Cobb said later in life that he regretted some of his earlier actions. He stated that he made some mistakes and that he likely would do some things differently if he had the chance to live his life again. He said, “I would have had more friends.”

Some 150 friends and relatives attended a brief funeral service in Cornelia, Georgia after Cobb lost a long battle with cancer on July 17, 1961. Only three former players attended his funeral – Ray Schalk, Mickey Cochrane, and Nap Rucker.@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Detroit Tigers (1905-1926)

Philadelphia Athletics (1927-1928)

Managed

Detroit Tigers (1921-1926)

Cobb accepted the job as Tiger manager reluctantly in 1921. His friend, Tris Speaker, had just guided the Indians to a World Series title as player/manager, and Cobb thought he could accomplish the same. However, he never desired the added attention, nor the aggrivation of dealing with his players (especially pitchers) nor the front office. He gained a reputation as an excellent batting coach, which was deserved. He helped transform Fred Haney and Lu Blue, as well as Heinie Manush, Harry Heilmann, and Bob Fothergill, into excellent big league hitters.

Similar: None truly comparable, though Tris Speaker had some of the same characteristics as an offensive player.

Linked: Matty McIntyre, Honus Wagner, Nap Lajoie, Sam Crawford, Walter Johnson, Joe Jackson, Babe Ruth, Harry Heilmann, Heinie Manush, Tris Speaker, Joe Wood, Dutch Leonard, Charlie Gehringer, Pete Rose, Lou Brock, Rickey Henderson

Nicknames: The Georgia Peach

Cobb’s friends could call him simply “Peach.” And yes, he had friends.

Uniform #: There were no uniform numbers in Cobb’s era. When the Tigers played their final game at the corner of Michigan and Trumball in 1999, every starter wore the uniform number of a Detroit legend. Center fielder Gabe Kapler wore a jersey without a number, in honor of Cobb. That jersey is in the Hall of Fame.

Family Tree

Ty had great hopes for his son, Ty Jr., but the boy was a disappointment as an athlete. Never wanting to draw comparisons to his famous father, and lacking the skill to play the game, Ty Jr. never warmed to baseball. In college, he irritated his father when he went out for the tennis team.

Best Season, 1911

Cobb’s finest efforts came in his seventh season. That year, he set career highs in runs (147), hits (248), doubles (47), triples (24), RBI (127), average (.420) and slugging percentage (.621). He led the AL in each category, as he also did with 83 stolen bases. He missed the Triple Crown by three homers as Frank “Home Run” Baker led with 11. He also set a then AL record with a 40-game hitting streak which helped him edge Shoeless Joe Jackson for the batting title. Over the course of the season Cobb struck out swinging just two times. The numbers overshadowed Cobb’s combative personality and won him the first ever MVP, then called the Chalmers Award.

Awards and Honors

1909 AL Triple Crown

1911 AL MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1907 World Series

1908 World Series

1909 World Series

Description

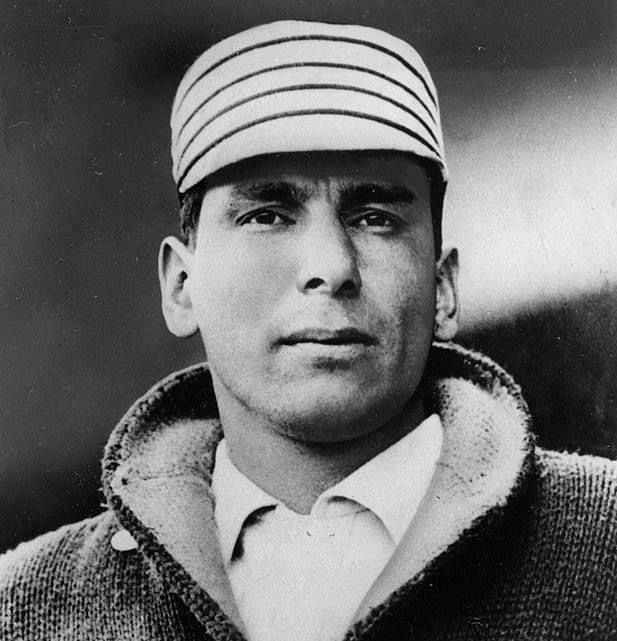

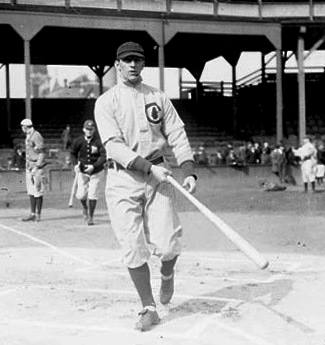

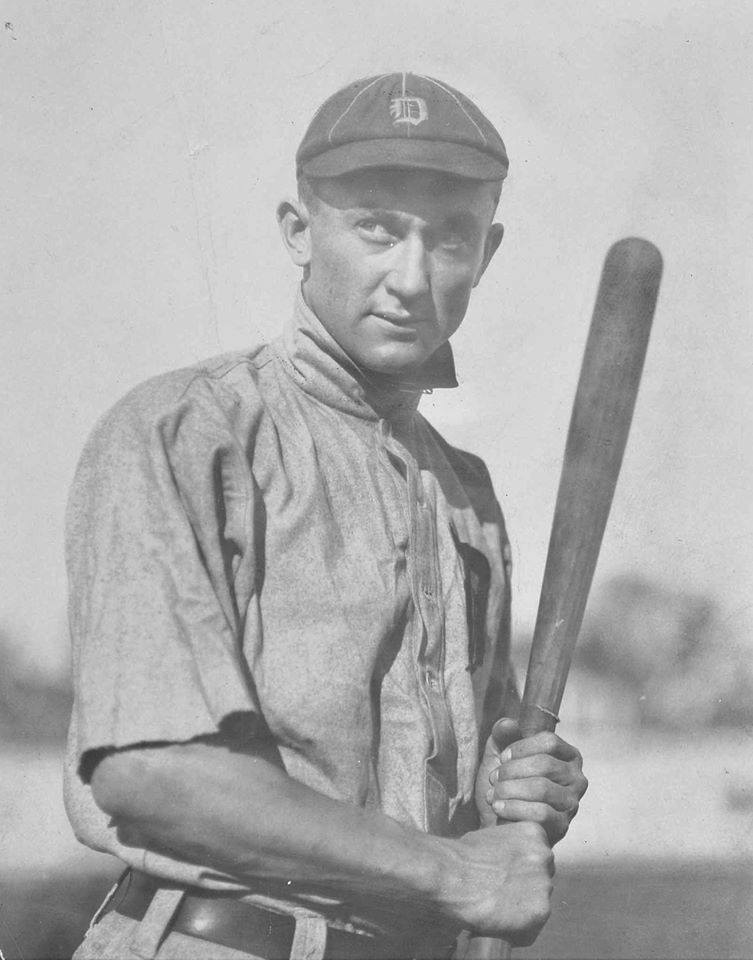

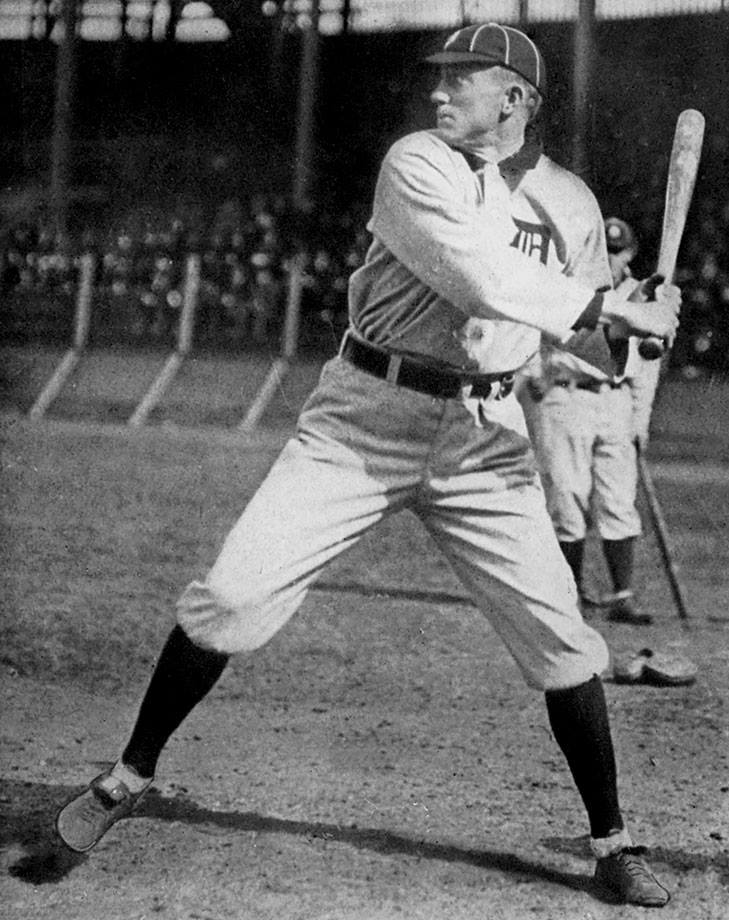

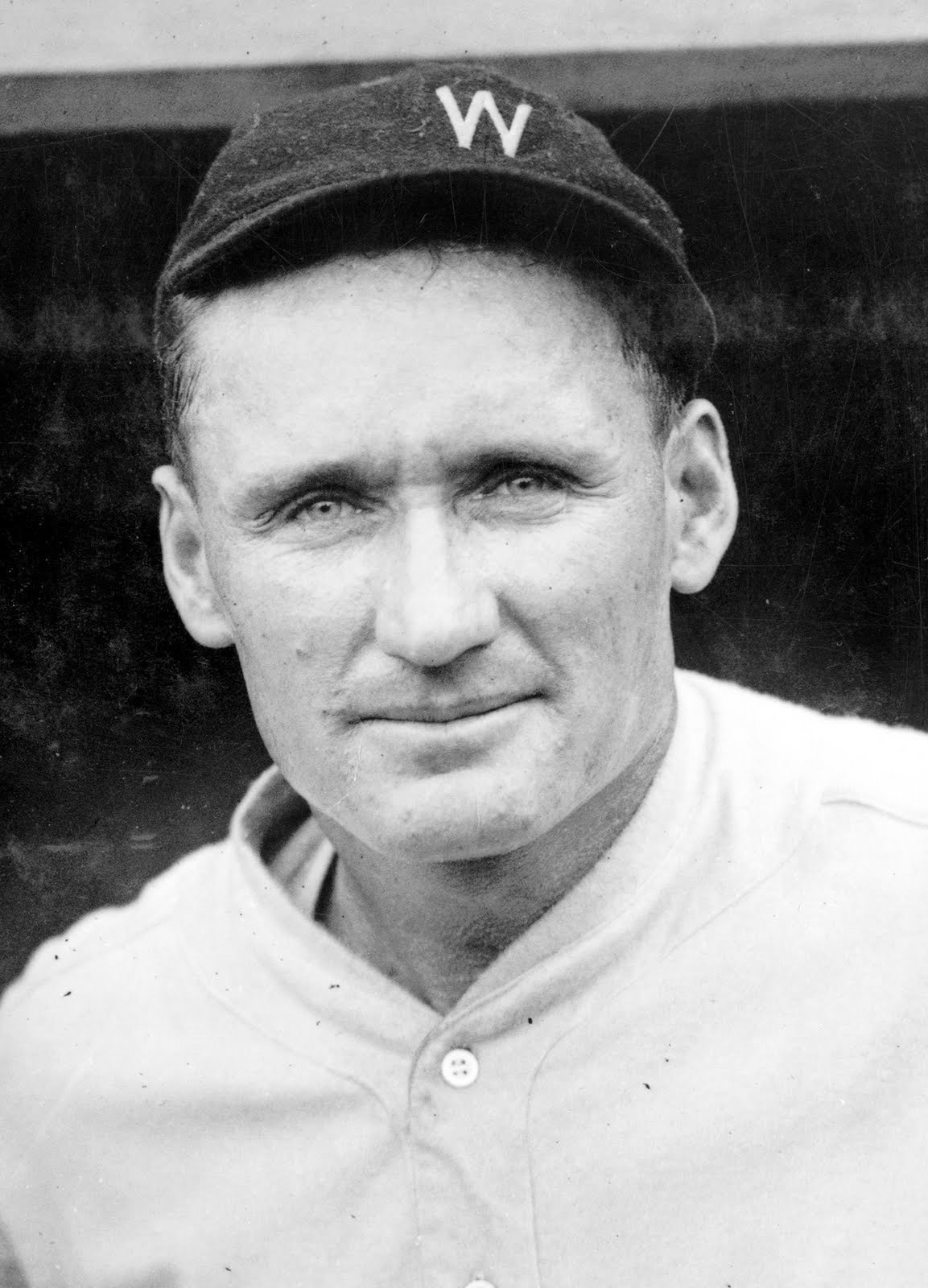

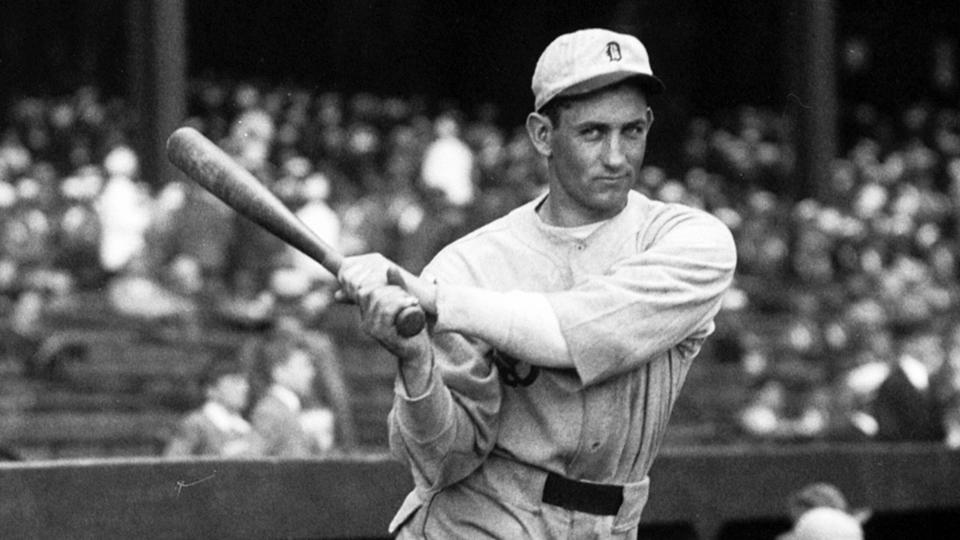

Cobb was a large man for his era, standing over 6-feet, one-inch tall and weighing around 190 pounds in his prime. He had light hair, which at times was described as blonde or even a light shade of orange. In his later years his hair receded. He had intense eyes and a toothy grin, which he flashed readily but never on the diamond. He was descibed as handsome and was very popular with female fans in Detroit and in his native Georgia.

Factoid

Ty Cobb became the first ball player to star in a movie, a drama written by Grantland Rice called Somewhere in Georgia.

Scouting Report

There wasn’t a way to get Cobb out consistently. However, if we look at the numbers, the pitchers who gave Cobb the most trouble were junkballers with peculiar or deceptive deliveries. It’s probably true to say that when pitchers faced Ty Cobb when the spitter was still legal, they put more goop on the ball, dirtier the ball with more licorice and tobacco, and resorted to the goofiest deliveries they could muster.

Full Bio

The eldest of three children, Tyrus Raymond Cobb grew up in Royston, Georgia, under the watchful eyes of his father, William; a schoolteacher, principal, newspaper publisher, state senator, and county school commissioner who urged Ty to study. When Ty went off to play professional baseball, his father sternly warned him “Don’t come home a failure.”

Cobb intended to become a physician or a prominent politician in Georgia but decided to pursue baseball when his athletic ability blossomed as a teenager. By 1905, the 18-year-old was a rookie outfielder for the Detroit Tigers. Two years later he won the American League batting title, the first of 12 he would capture.

It is unlikely that anyone can beat his lifetime batting average. In his 24 seasons he topped the .300 barrier 23 times. Cobb’s first great season came in 1907, and the Tigers rode that success all the way to the World Series. That season the outfielder’s batting average was .350 – the best in the AL. Other league bests included 212 hits, 119 RBI’s, and 49 stolen bases. Cobb did not stop there. He won nine consecutive batting titles starting in 1907.

Cobb might be remembered best for his intimidating playing style. He was never afraid to go to extremes to win a game. He could take pain, as well as hand it out. “I recall when Cobb played a series with each leg a mass of raw flesh,” Grantland Rice wrote. “He had a temperature of 103 and the doctors ordered him to bed for several days, but he got three hits, stole three bases, and won the game. Afterward he collapsed at the bench.”

Cobb looked for every possible way to win. He used his great speed and precision hitting as the best weapons available in the dead-ball, strong-pitching era. Cobb studied pitchers and took advantage of their weaknesses. Against Walter Johnson, the great Washington right-hander who was afraid of hitting batters with fastballs, Cobb crowded the plate. Johnson worked him outside, fell behind in the count, and finally threw hittable pitches over the plate. Cobb clobbered ball after ball.

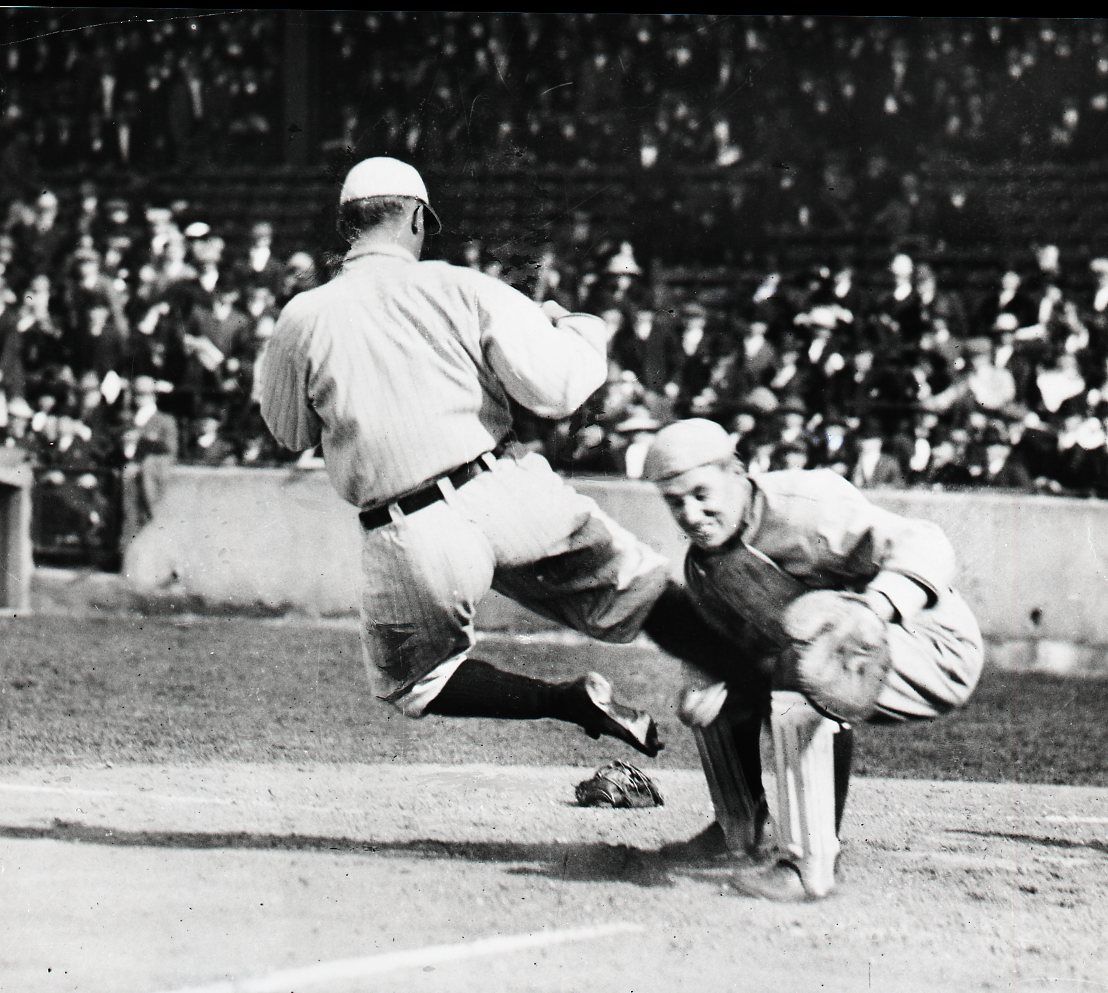

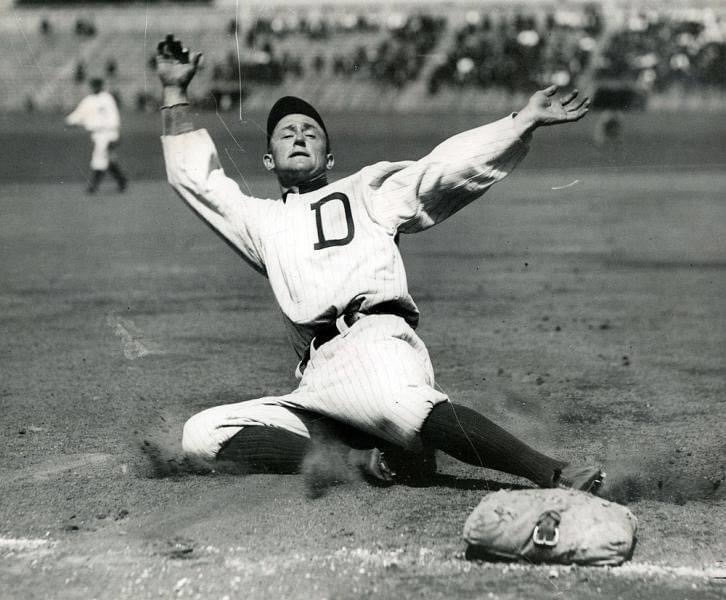

Cobb paid the price for success. He would practice sliding until his legs were raw. He would place blankets along the baseline, and he practiced bunting a ball into a basket. During the winter he hunted through daylight hours in weighted boots so that his legs would be strong for the upcoming campaign. He never failed to capitalize on an opportunity to gain an edge over his opponents, most of whom admired his drive to succeed.

Cobb engaged in annual haggles with Detroit executives before signing his contract, and those earnings were invested wisely, mostly in General Motors and Coca-Cola stock, which made him baseball’s first millionaire.

Cobb’s late career was marred by a gambling episode that involved Tris Speaker, one of his few friends in baseball. Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis helped conceal the details of the scandal to ensure the two great ballplayers would not tarnish their image nor that of the game.

Known for his combative personality, it was that tempestuous attitude that gave Cobb his edge and helped him achieve excellence. He was shrewd and methodical, careful to learn the weakness of every opponent. As a baserunner he was unmatched in daring and skill, leading the league in steals six times. When the game changed in the 1920s and the home run became vogue, Cobb steadfastly stuck to “inside baseball” – bunting, running and slashing his way to more than 4,000 career hits.

Where He Played: OF (2,934 games), 1B (14), pitcher (3), 2B (2), 3B (1). Cobb was primarily a center fielder, with the notable exception of the Tigers pennant years of 1907-1909.

Minor League Experience

1904-1905: Augusta Tourists (South Atlantic League)

1904: Anniston (Alabama-Texas- Louisiana League)

Big League Debut: August 30, 1905

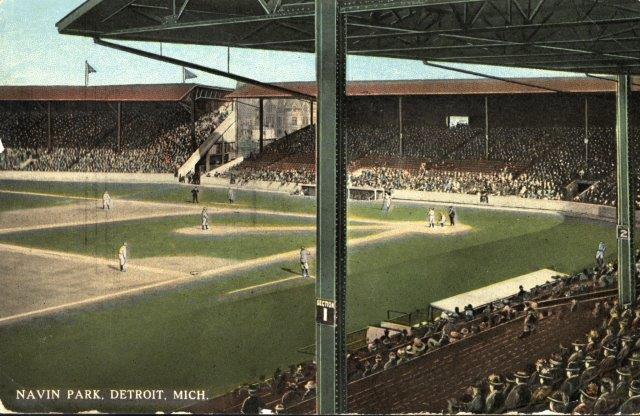

Cobb had never been above the Mason-Dixon Line, and now he was on his way to a city larger than any he had ever seen. After a few missed connections, Cobb arrived in Detroit by train on August 29, and checked in to a hotel within walking distance of Bennett Park. Detroit’s Bennett Park was located on the corner of Michigan and Trumbull in the heart of the city in a section called “Corktown,” because of the predominance of Irish immigrants living there. Cobb reported to the park on August 30, just over three weeks after the death of his father. He was ready to start his big league career. The Detroit Free Press, writing of his arrival and his minor league batting success, speculated that the young Georgian “wouldn’t pile up anything like that in this league.”

Cobb saw action immediately with the Tigers, who were hosting the New York Highlanders in the second of a three-game series. Bennett Park was named for Charlie Bennett, a star for the National League’s Detroit Wolverines in the 1880s. A catcher, Bennett’s career was ended abruptly when he lost both of his legs in a terrible train accident in 1894. Bennett had been tremendously popular in Detroit, and in 1900, when the city earned a team in the Western League (later to become the American League), their ballpark was named in his honor.

The Highlanders, later to be known as the Yankees, started ace “Happy Jack” Chesbro, a master of the spitball. The previous season, Chesbro had won an amazing 41 games and pitched more than 400 innings for the New York club. The Tigers, managed by Bill Armour, countered with “Big George” Mullin, a fidgety right-hander from Wabash, Indiana. In front of an afternoon crowd of approximately 1,200 fans, Cobb hit fifth in the lineup, playing center field. Armour’s Tigers, due to injury, had a shortage in the outfield. In the bottom of the first inning, the Tigers hit Chesbro hard, putting together a double, single, and a sacrifice bunt to plate one run and move another runner to third. With one out, the left-handed hitting Cobb strolled to the plate for his first major league at-bat. Using the hands-apart grip that he’d perfected as a boy in Georgia, 18-year old Ty Cobb peered out at Jack Chesbro and tried to overcome the nerves that were causing his stomach to twist and turn. The first pitch he saw was a high fastball that he swung through and missed. The next offering from Chesbro was a spitter that fooled Cobb for strike two. Chesbro then returned to his fastball, sending a pitch into the heart of the strike zone that Cobb met with a flick of his bat. The ball soared into the left-center field gap where it was retrieved by New York left fielder Noodles Hahn, whose throw to second base was a split second too late to catch the sliding Georgian. “Pinky” Lindsay, the Tigers’ runner on third, trotted home to make the score 2-0. Ty Cobb had his first hit, first run batted in, and first double in the big leagues, having victimized one of the best pitchers in the league. Ty walked against Chesbro his next time up, and with Sam Crawford in front of him on second base, Cobb was out on the backend of a double steal attempt, but it did little to dampen the day for the Tigers, as they vanquished the Highlanders, 5-3. In center field, Cobb handled two putouts without incident and his first big league game was under his belt.

— from Ty Cobb, by Dan Holmes

His Arsenal: The Pitches He Threw

Cobb actually toed the rubber three times in his career, He did it twice in 1918 at the tail-end of the season when he thought he may never play again (he was off to serve in the war). Later, as player/manager, Cobb inserted himself in relief. He set down all three batters he faced. For his career, Cobb had a 3.60 ERA in five innings, with no strikeouts and two walks. Like most position players, he thought he could pitch if he had concentrated his efforts on it. A part of Cobb probably wanted to pitch to see if he could do the things Ruth had done as a pitcher/batter.

Post-Season Notes

The story goes that when Cobb reached base for the first time in the 1909 World Series, he yelled down to Pirates shortstop Honus Wagner, “I’m comin’ down on the next pitch, krauthead!” Which he did.

When he slid in with dust flying, Wagner slapped the tag on Cobb, some say woth a little extra force, and growled at the Tiger star: “Get back in your cage, animal.”

Feats: Six times in his career, Cobb reached base and proceeded to steal second, third and home. The first time he did it was in 1907, the final time was in 1924… On May 5, 1925, Cobb blasted three homers, a double and two singles in one game, for a then-record 16 total bases. The next day he hit two more homers.

Milestones

Collected his 3,000th hit on August 19, 1921; his 4,000th hit on July 19, 1927, against the Tigers, as a member of the Philadelphia A’s.

Notes

It’s well-chronicled that Cobb never won a World Series, though he played in three Fall Classics, all as a young man, prior to his peak as a player. His teams were competitive, however: in his 19 seasons as a regular, the teams he played on were 1542-1331, a .537 winning percentage… No player in baseball history drove in more teammates than did Cobb. When you subtract home runs from RBI, you have the number of teammates batted in (TBI), Cobb leads all-time with 1,843.

Injuries and Explanation for Missed Playing Time

In June of 1920, just as he was getting hot with the bat, Cobb suffered the worst injury of his playing career. As he chased a fly ball in right-center in Chicago’s Comiskey Park, he collided with Flagstead and fell to the ground in pain. He had wrenched his left knee, tearing ligaments. After consulting a specialist in Chicago, Cobb was sent home to Augusta to recuperate. He was out of the lineup for more than a month, not returning until July 8, when he delivered a dramatic ninth inning game-tying single against the Yankees. With Bobby Veach on third representing the winning run, he and Cobb attempted a double steal. Despite his still-aching knee, Cobb hustled safely into second base as Veach scored on a bad throw to give the Tigers the victory. Two days later, Cobb was back in the lineup for good, starting a 20-game hitting streak in which he batted .471.

Hitting Streaks

40 games (1911)

40 games (1911)

35 games (1917)

35 games (1917)

25 games (1906)

25 games (1906)

21 games (1926)

21 games (1927)

21 games (1926)

21 games (1927)

Transactions

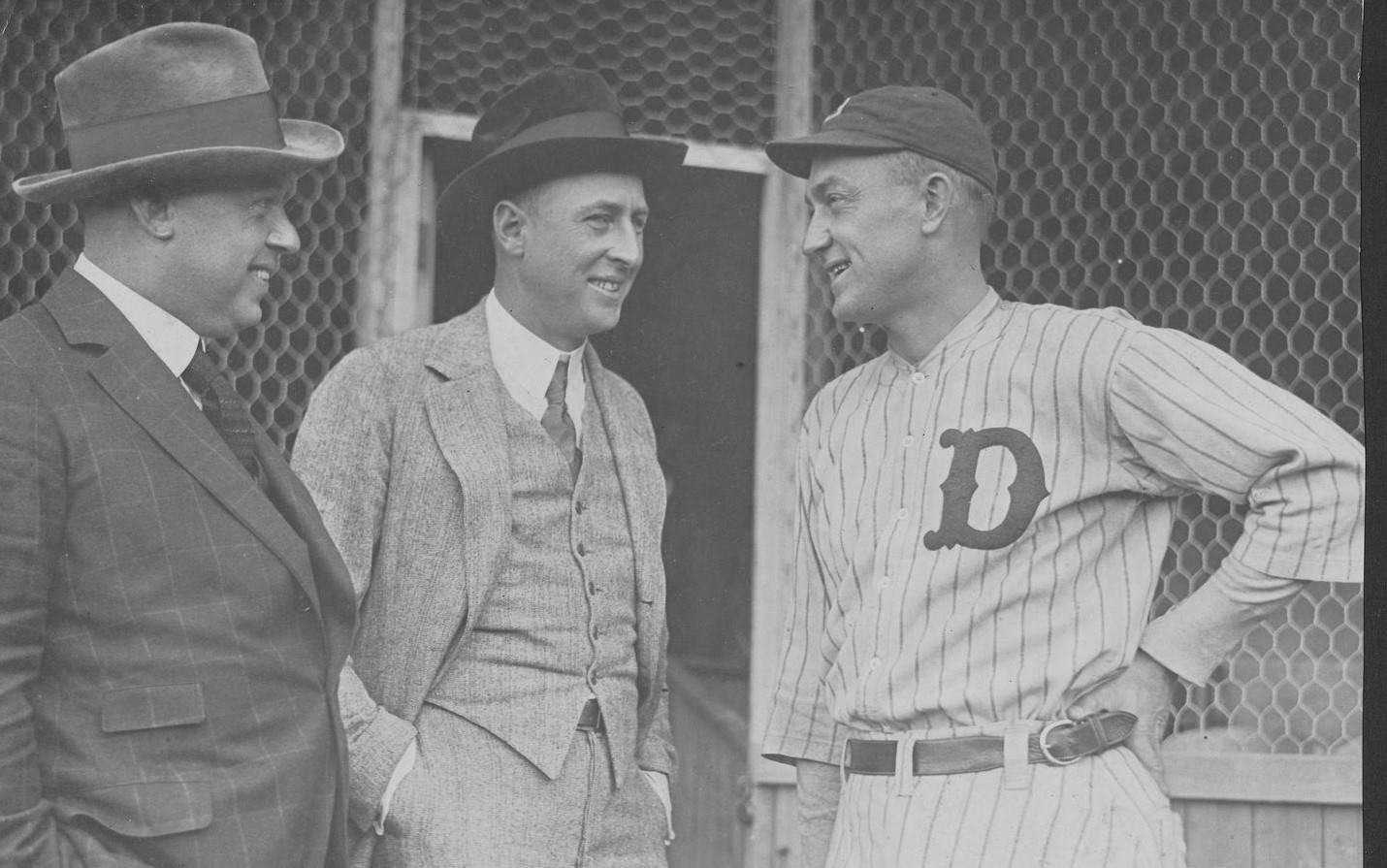

After the gambling scandal that nearly ruined Cobb’s reputation, Ty was asked to leave the Detroit Tigers as player /manager following the ’26 season. He successfully fought to clear his name, and then retired to his home in Augusta, Georgia. But in February, Connie Mack made a much-publicized visit to Cobb and convinced the veteran to play one more season with his Philadelphia A’s. Cobb signed for $40,000 with the option for a $30,000 bonus should the A’s attendance rise above a certain level. Cobb was attracted by the prospect of proving himself after the gambling accusations. He also liked the notion of playing on a winning ball club.

Factoid

Playing in Detroit, the growing “Motor City” most of his career, Ty Cobb enjoyed fine cars. He even raced automobiles in the early 1910s, before he was asked to halt the dangerous practice by Tigers ownership.

Quotes About Cobb

“He did everything except steal first base. And I think he even did that in the dead of night.” — Rube Bressler

“He played as if he had brains in his feet.” — Branch Rickey

“Every time at-bat for him was a crusade, and that’s why he’s off in a circle by himself.” — Charlie Gehringer

Quotes From Cobb

“I find little comfort in the popular Cobb as a spike-slashing demon of the diamond with a wide streak of cruelty in his nature. The fights and feuds I was in have been steadily slanted to put me in the wrong.”

“Baseball is a red-blooded sport for red-blooded men….a struggle for supremacy, survival of the fittest.”

Factoid

One of Ty Cobb’s best friends was the president of Coca-Cola Robert Woodruff, a fellow Georgian and avid hunter.

Home Run Facts

Navin Field was not particularly easy to homer in during Cobb’s day. He hit 111 homers as a Tiger, with 79 (71%) coming on the road. The park had that deep center field and the gaps were also cavernous. It was short down the line, but Cobb didn’t pull the ball as much as power hitters today would. 46 of Cobb’s 117 career home runs were inside-the-park.

Hall of Fame Artifacts

Sliding pants, which he wore under his uniform to protect his legs; baseball bats, signed baseball, his glove, spikes, wool Detroit Tigers sweater (circa 1918), dentures, and his diary, among other things.

Matchup Data

Ty Cobb batted .366 against the best pitcher in baseball during his career: Walter Johnson.

Trivia: After his rookie season, who was the only player to pinch-hit for Ty Cobb?

Answer: Jimmy Dykes in 1928.

Replaced

Matty McIntyre, who didn’t welcome the challenge to his job.

Replaced By

Bing Miller, who had actually been around a while, but lost his starting job when Mack signed Cobb and Speaker in 1927-1928. Miller was a fine player, batting .311 for his career.

Best Strength as a Player

Baserunning and batting eye.

Largest Weakness as a Player

Cobb had no weakness on a ball field.

Learn More about Ty Cobb

Ty Cobb Museum

Other Resources & Links