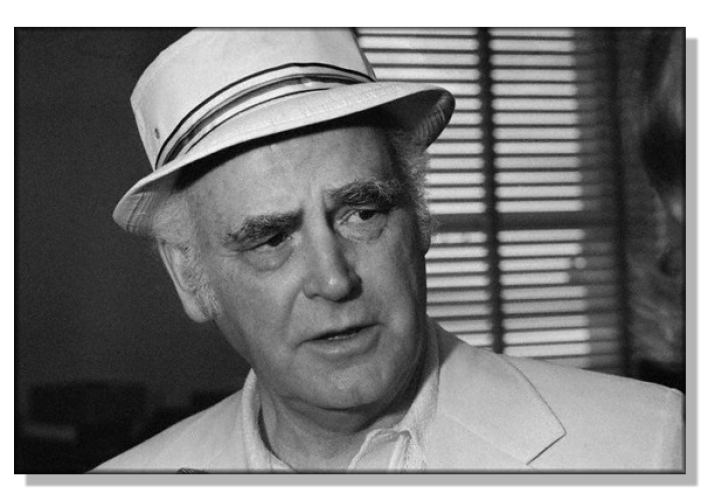

One of the most flamboyant, innovative, and controversial baseball club owners ever, Charles Finley began as a semi-pro first baseman-manager in Indiana. Near-fatal tuberculosis in 1946 ended his playing career but inspired him to found a life insurance empire. Outbid for the Kansas City A’s in 1960 by Arnold Johnson, Finley acquired the team a few months later when Johnson died. The A’s had been sending such stars as Roger Maris, Clete Boyer, and Ralph Terry to the Yankees in exchange for washed-up journeymen; Finley immediately suspended dealings with New York and, as his own general manager, soon established a knack for acquiring unheralded talent like Ed Charles and Jose Tartabull.

Finley’s first of many feuds with players and managers commenced at the 1962 All-Star break when he ordered Manny Jimenez, who was leading the AL with a .350 average, to start hitting home runs. Manager Hank Bauer took Jimenez’s side and was fired after the season. Jimenez slumped and was sent down in 1963. In mid-1967, Finley fined and suspended young pitcher Lew Krausse for “rowdyism,” and publicly berated his players over an insignificant airplane incident. A near-mutiny by the players followed. Finley fired manager Alvin Dark, then released Ken Harrelson, the team’s best hitter, who had been quoted as saying that Finley was “a menace to baseball.” Signed by the Red Sox, Harrelson helped them to the pennant, and won the AL RBI title the following year.

Finley had already established a reputation as a cantankerous buffoon by trading for sluggers Jim Gentile and Rocky Colavito, then building a bizarre “pennant porch” designed to increase their home run production. He later paraded a mule named Charley O about the field, into cocktail parties, and even through hotel lobbies. He relocated the A’s Double-A franchise to Birmingham because he was born there. He introduced orange baseballs, ball girls, and a mechanical rabbit that gave baseballs to the umpires. He advocated night World Series games in an effort to boost fan interest.

Meanwhile, Finley signed Jim Hunter and dubbed him Catfish to give him press appeal, concocting a story set in Hunter’s childhood to justify the nickname. Finley also signed Reggie Jackson, Sal Bando, Vida Blue, Bert Campaneris, and a host of others who became the nucleus of his Oakland dynasty. He shifted the club from Kansas City to Oakland after the 1967 season in a move he later acknowledged as his one big mistake. In a half-empty stadium, the A’s were contenders during 1969 and 1970, then won five straight division titles in 1971-75 and World Championships in 1972-74.

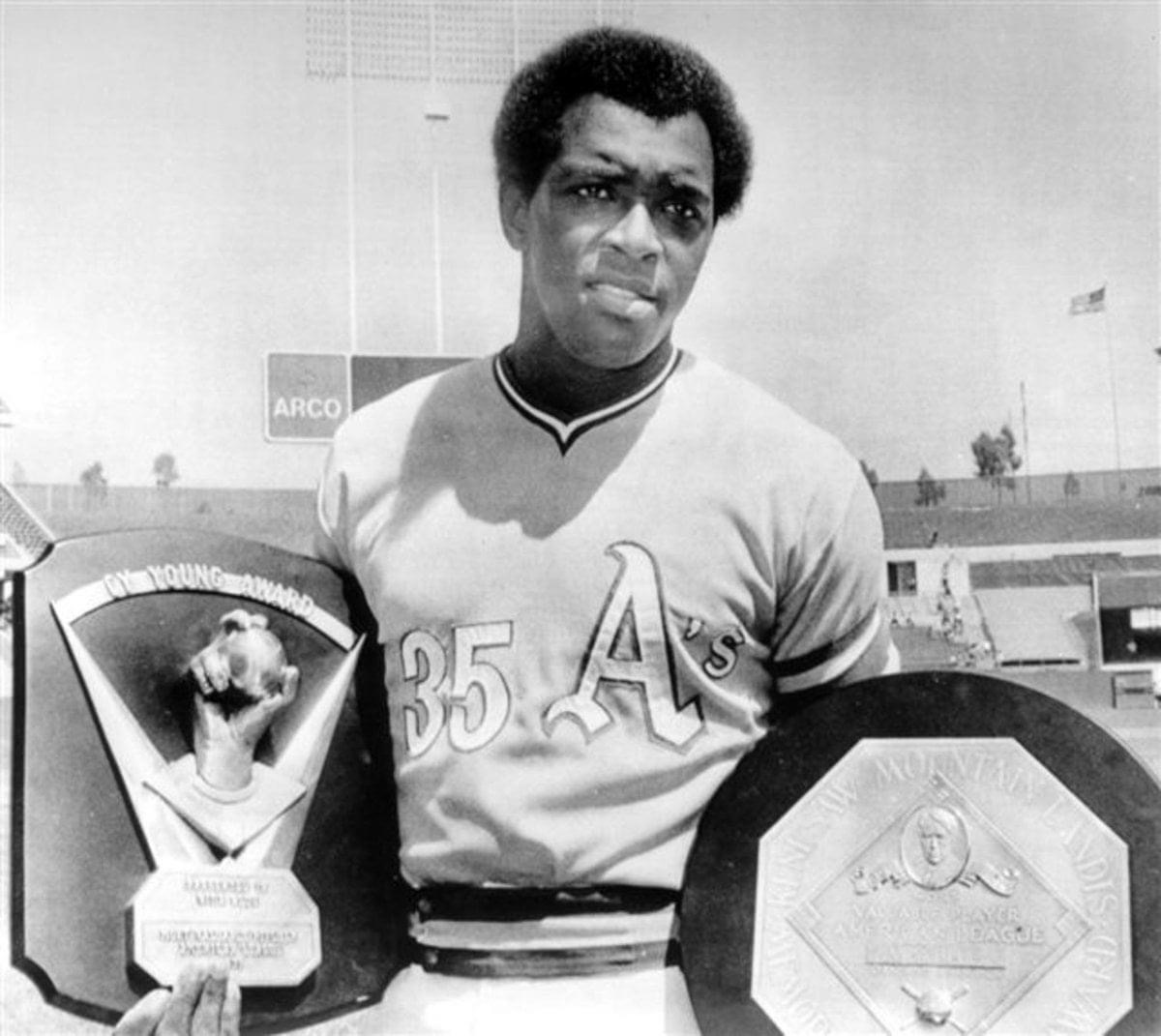

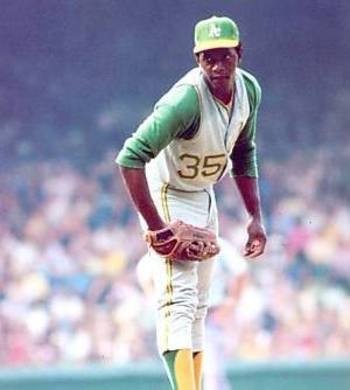

Finley was named TSN Man of the Year for 1972, but continued having disputes with players. After Reggie Jackson hit 47 HR in 1969, Finley, during a prolonged contract dispute, threatened to send him back to the minors. Similar bitterness followed when Vida Blue won the Cy Young Award in his first full season, 1971. Both times, Commissioner Bowie Kuhn intervened to help bring about a resolution. In the 1973 World Series, Finley fired Mike Andrews after the reserve infielder committed two consecutive errors in the 12th inning of Oakland ‘s Game Two loss to the Mets. Other A’s and manager Dick Williams rallied to Andrews’s defense. Kuhn forced Finley to reinstate the player. Williams resigned after winning the Series, and Finley replaced him with Alvin Dark.

Under Dark, the A’s won another World Championship in 1974. But after the season, Catfish Hunter was declared a free agent by arbitrator Peter Seitz because Finley had failed to make contractually stipulated payments for Hunter into an insurance annuity fund. Even without Hunter, the A’s easily won their division in 1975. In the spring of 1976, Finley traded Jackson to the Orioles. During the season, he tried to sell Joe Rudi and Rollie Fingers to the Red Sox and Vida Blue to the Yankees, and did sell Paul Lindblad to the Rangers. In desperate financial trouble because of low attendance, Finley claimed he needed the money to sign free agents and rebuild. Kuhn disagreed, voiding the sales of Rudi, Fingers, and Blue as not being “in the best interests of baseball.” Kuhn later voided another sale of Blue, to the Reds. Meanwhile, major league players won the right to play out their options, and seven A’s did so in 1976. Despite the uncompensated losses, Finley rebuilt, and the A’s were en route to yet another division title in 1981 when he sold the club to the Levi-Strauss company.

Notable Events and Chronology for Charles Finley Career

Sponsor this Page

Listen to Voices From The Past on Our Podcast

The Daily Rewind

on Apples Podcast | Spotify | Google | Stitcher

And connect with us wherever else you listen to Podcast and hangout!

This Day In Baseball Has – Over 1,000 videos!