Moe Berg Stats & Facts

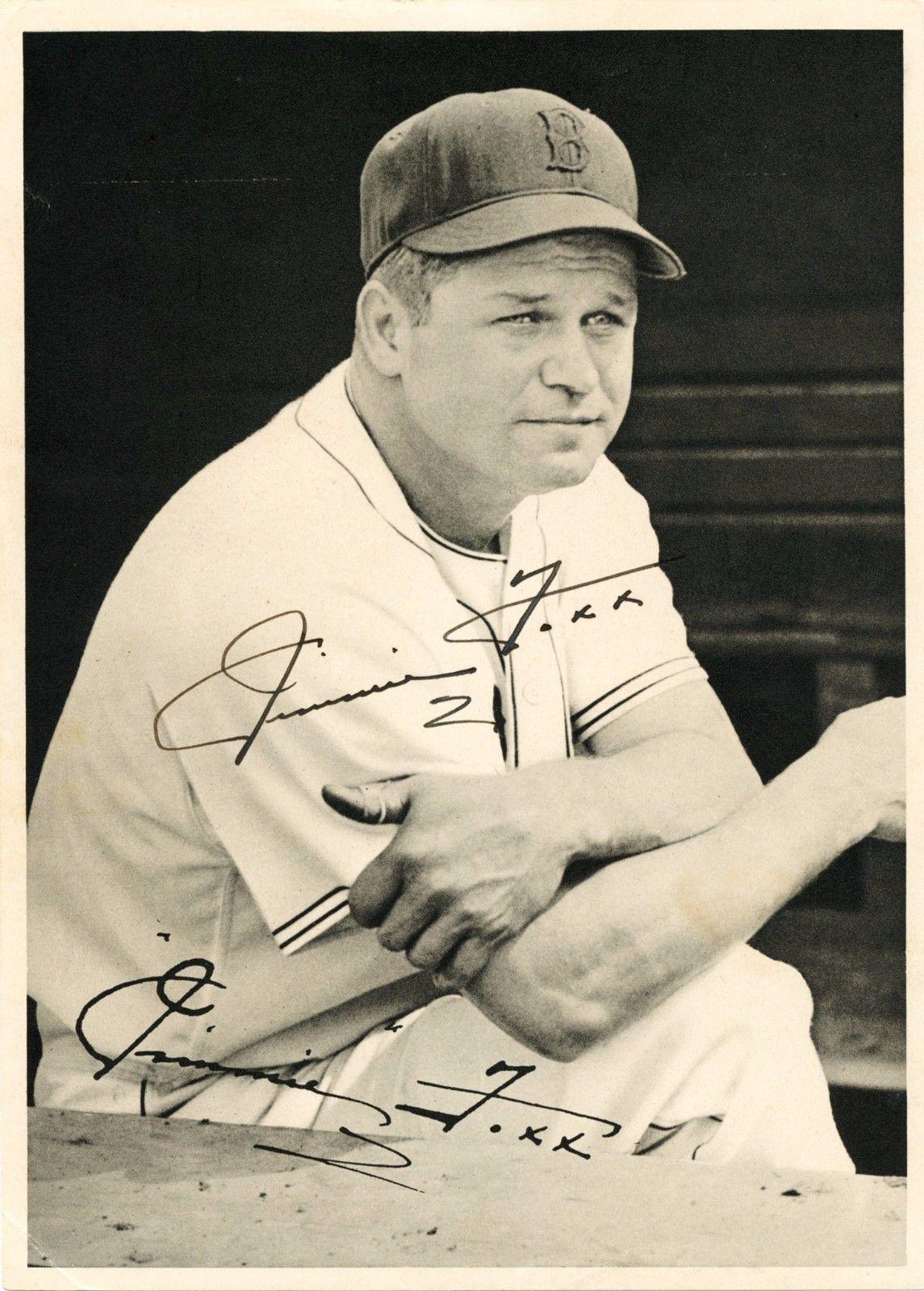

Moe Berg Essentials

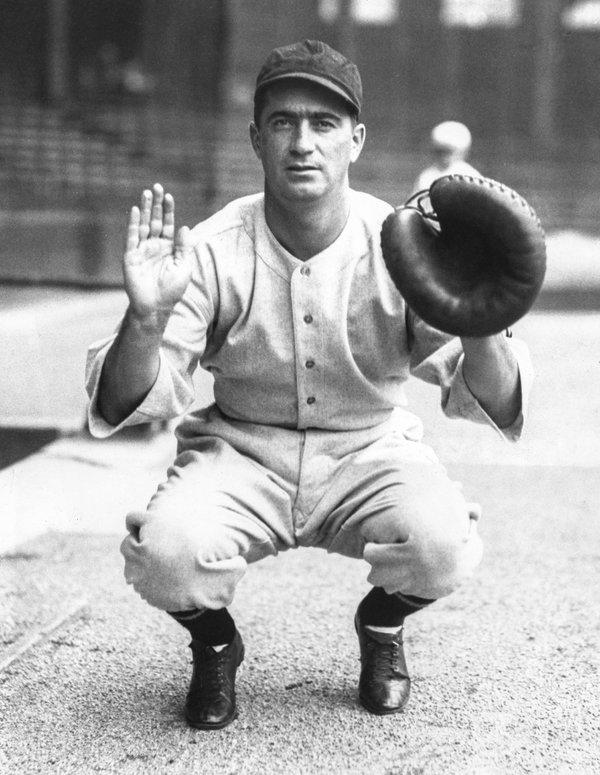

Positions: Catcher

Bats: R Throws: R

Height: 6-1 Weight: 185

Born: Sunday, March 02, 1902 in New York, NY USA

Died: 5 29 1972 in Belleville, NJ USA

Debut: 6/27/1923

Last Game: 9/1/1939

Full Name: Morris Berg

Notable Events and Chronology for Moe Berg Career

Among the most scholarly professional athletes ever, Berg was an alumnus of three universities, lawyer, mathematician, linguist, and poor hitter, eliciting the comment: “He can speak 12 languages but can’t hit in any of them.” His ability to handle young pitchers and his reputation as a bullpen mystic kept him in the majors, where his roommates wondered at his sacrosanct clutter of books and newspapers stacked in dozens of piles. He professed belief that his newspapers were “alive” and could “die” from being looked at by someone else. On occasion he braved snowstorms to purchase replacements for “deceased” newspapers.

Casey Stengel called him “the strangest man ever to play baseball” even before it was known he had served America as a spy. Some may have wondered why a third-string catcher like Berg went to Japan in the early 1930s with the likes of Ruth and Gehrig on an all-star traveling team. In fact, Berg was assigned to take espionage photos. During WWII, he became one of America’s most important atomic spies, gathering vital information on top German scientists and even performing some missions that might have required assassination. He declined the Medal of Merit for his wartime service and never wrote his memoirs after being angered by an assigned co-author who confused him with “Moe” of the Three Stooges.

Berg fit the classic spy image: dark, heavy-featured, mysterious, sybaritic, courageous, and impeccably mannered. Women were attracted to the cultured, lifelong bachelor. When he was criticized for “wasting” his intellectual talent on the sport he loved, Berg replied: “I’d rather be a ballplayer than a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.”

“He [Moe Berg] bluffs his way up onto the roof of the hospital, the tallest building in Tokyo at the time. And from underneath his kimono he pulls out a movie camera. He proceeds to take a series of photos panning the whole setting before him, which includes the harbor, the industrial sections of Tokyo, possibly munitions factories and things like that. Then he puts the camera back under his kimono and leaves the hospital with these films,” says Nicholas Dawidoff, a Berg biographer.

Early life

Moe Berg was the third and last child of Bernard Berg, a pharmacist, and Rose Tashker, a homemaker, both Jewish, who lived in the Harlem section of New York City, New York, a few blocks from the Polo Grounds. When Berg was three and a half, he begged his mother to let him start school. In 1906, Bernard Berg bought a pharmacy in West Newark. In 1910 the Berg family moved again, to the Roseville section of Newark. Roseville offered Bernard Berg everything he wanted in a neighborhood—good schools, middle-class residents, and very few Jews.

Berg began playing baseball at the age of seven for the Roseville Methodist Episcopal Church baseball team under the less ethnic pseudonym Runt Wolfe. In 1918, at the age of 16, Berg graduated from Barringer High School. During his senior season, the Newark Star-Eagle selected a nine-man “dream team” for 1918 from the city’s best prep and public high school baseball players, and Berg was named the team’s third baseman. Barringer was the first in a series of institutions Berg joined in his life where his religion made him unusual. Most of the other students were East Side Italian Catholics or Protestants from Forest Hill, but there were not many Jews, just as Bernard wanted it.

After graduating from Barringer, Berg enrolled in New York University. He spent two semesters there and played baseball and basketball. In 1919 he transferred to Princeton University, and never again mentioned that he attended NYU for a year, presenting himself exclusively as a Princeton man. Berg received a B.A., magna cum laude in modern languages. He had studied seven languages: Latin, Greek, French, Spanish, Italian, German and Sanskrit. His Jewish heritage and modest finances combined to keep him on the fringes of Princeton society, where he never quite fit in.

During his freshman year, Berg played first base on an undefeated team. Beginning in his sophomore year, he was the starting shortstop. He was not a great hitter and was a slow baserunner, but he had a strong, accurate throwing arm and sound baseball instincts. In his senior season, he was captain of the team and had a .337 batting average, batting .611 against Princeton’s arch-rivals, Harvard and Yale. Crossan Cooper, Princeton’s second baseman, and Berg communicated plays in Latin when there was a man on second base.

On June 26, 1923, Yale defeated Princeton 5–1 at Yankee Stadium to win the Big Three title. Berg had an outstanding day, getting two hits in four at bats (2–4) with a single and a double, and making several marvelous plays at shortstop. Both the New York Giants and the Brooklyn Robins desired “Jewish blood” on their teams, to appeal to the large Jewish community in New York, and expressed interest in Berg. The Giants were especially interested, but they already had two future Hall of Famers at shortstop, Dave “Beauty” Bancroft and Travis Jackson. The Robins were a mediocre team, where Berg would have a better chance to play. On June 27, 1923, Berg signed his first big league contract for $5,000 ($64,000 today) with the Robins.

Major league career

Early career (1923–1925)

Berg’s first game with the Robins came the very next day against the Philadelphia Phillies at the Baker Bowl. Berg came in at the start of the seventh inning, replacing Dutch Ruether, when the Robins were winning 13–4. Berg handled five chances without an error and caught a line drive to start a game-ending double play. He made a hit in his only at bat, getting a single up the middle against Clarence Mitchell, and scoring a run. For the season, Berg batted .187 and made 21 errors in 47 games, his only National League experience.

After the season ended, Berg took his first trip abroad, sailing from New York to Paris. He settled in the Latin Quarter in an apartment that overlooked the Sorbonne, where he enrolled in 32 different classes. In Paris he developed a habit he kept for the rest of his life: reading several newspapers daily. Until Berg finished reading a paper, he considered it “alive” and refused to let anyone else touch it. When he was finished with it, he would consider the paper “dead” and anybody could read it. In January 1924, instead of heading back to New York and getting himself into shape for the upcoming baseball season, Berg toured Italy and Switzerland.

During spring training at the Robins facility in Clearwater, Florida, manager Wilbert Robinson could see that Berg’s hitting had not improved, and optioned him to the Minneapolis Millers of the American Association. Berg did not take the demotion well and threatened to quit baseball, but by mid-April he reported to the Millers. Berg did very well once he became the Millers’ regular third baseman, hitting close to .330, but in July his average plummeted and he was back on the bench. On August 19, 1924 Berg was loaned to the Toledo Mud Hens, a poor team ravaged by injuries. Berg was immediately inserted into the lineup at shortstop when Rabbit Helgeth refused to pay a $10 ($130 today) fine for poor play and was suspended. Major league scout Mike Gonzalez sent a telegram to the Dodgers evaluating Berg with the curt, but now famous, line, “Good field, no hit.” Berg finished the season with a .264 average.

By April 1925, he was starting to show promise as a hitter with the Reading Keystones of the International League. Because of his .311 batting average and 124 runs batted in, the Chicago White Sox exercised their option they had with Reading, paying $6,000 ($75,000 today) for him, and moved Berg up to the big leagues the following year.

Career as a catcher (1926–1934)

The 1926 season began with Berg informing the White Sox that he would skip spring training and the first two months of the season to complete his first year of law school at Columbia University, and Berg did not join the White Sox until May 28. Bill Hunnefield was signed by the White Sox to take Berg’s place at shortstop, and was having a very good year, batting over .300. Berg played in only 41 games, batting .221.

Berg returned to Columbia after the season to continue working on his law degree. Despite White Sox owner Charles Comiskey offering him more money to come to spring training, Berg declined, and informed the White Sox that he would be reporting late for the 1927 season. Noel Dowling, a professor to whom Berg explained his situation, told Berg to take extra classes in the fall, and said that he would arrange with the dean a leave of absence from law school the following year, 1928.

Because he reported late, Berg spent the first three months of the season on the bench. In August, a series of injuries to catchers Ray Schalk, Harry McCurdy and Buck Crouse left the White Sox in need of somebody to play the position. Schalk, the White Sox player/manager, selected Berg, who did a fine job filling in. Schalk arranged for former Philadelphia Phillies catcher Frank Bruggy to meet the team at their next game, against the New York Yankees. Bruggy was so fat that pitcher Ted Lyons refused to pitch to him. When Schalk asked him who he wanted to catch, Lyons selected Berg.

In Berg’s debut as a starting catcher, he had to worry not only about catching Lyons’s knuckleball, but also about facing the Yankees’ Murderers’ Row lineup, which included Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig and Earle Combs. Lyons beat the Yankees 6–3, holding Ruth hitless. Berg made the defensive play of the game when he caught a poor throw from the outfield, spun and tagged out Joe Dugan at the plate. Berg caught eight more times during the final month and a half of the season.

To prepare for the 1928 season, Berg traveled to a lumber camp in New York’s Adirondack Mountains three weeks prior to reporting to the White Sox spring training facility in Shreveport, Louisiana. The hard labor did wonders for him, as he reported to spring training on March 2, 1928 in excellent shape. By the end of the season, Berg had established himself as the starting catcher.

At law school, Berg failed Evidence and did not graduate with the class of 1929, but he did pass the New York State bar exam. Berg repeated Evidence the following year, and on February 26, 1930 he received his LL.B.[21] On April 6, during an exhibition game against the Little Rock Travelers, Berg’s spikes caught in the soil as he tried to change directions, and he tore a knee ligament.

Berg was back in the starting lineup on May 23, 1930, but his knee would not allow him to play every day. He ended up getting into only 20 games the whole season and finished with a .115 batting average. During the winter, he took a job with the respected Wall Street law firm Satterlee and Canfield (now Satterlee, Stephens, Burke & Burke). The Cleveland Indians picked up Berg on April 2, 1931 when Chicago put him on waivers, but he played in only 10 games, and had 13 at bats and only 1 hit for the entire season.

“Yeah, I know, and he can’t hit in any of them.”

— Dave Harris, Senators’ outfielder, when told that Berg spoke seven languages

The Indians gave Berg his unconditional release in January 1932, but with catchers hard to come by, Clark Griffith, owner of the Washington Senators, invited him to spring training in Biloxi, Mississippi. Berg made the team, playing in 75 games while committing no errors. When starting catcher Roy Spencer went down with an injury, Berg stepped in, throwing out 35 base runners while batting .236.

First trip to Japan

Retired ballplayer Herb Hunter arranged for three players, Berg, Lefty O’Doul and Ted Lyons, to go to Japan to teach baseball seminars at Japanese universities during the winter of 1932. On October 22, 1932, the group of three players began their circuit of Meiji, Waseda, Rikkyo, Todai (Tokyo Imperial), Hosei, and Keio universities, the members of the Tokyo Big Six University League. When the other Americans returned to the United States after their coaching assignments were over, Berg stayed behind to explore Japan. He went on to tour Manchuria, Shanghai, Peking, Indochina, Siam, India, Egypt and Berlin.

Despite his desire to go back to Japan, Berg reported to the Senators training camp on February 26, 1933 in Biloxi. He played in just 40 games during the season, and batted only .185. The Senators won the pennant, but lost to the Giants in the World Series. Cliff Bolton, the Senators’ starting catcher in 1933, demanded more money in 1934. When the Senators refused to pay him more, he sat out and Berg got the starting job. On April 22, Berg made an error, his first fielding mistake since 1932—an American League record of 117 consecutive errorless games. On July 25, the Senators gave Berg his unconditional release. He soon returned to the big leagues, however, after Cleveland Indians catcher Glenn Myatt broke his ankle on August 1. Indians manager Walter Johnson, who had managed Berg in 1932, offered Berg the reserve catching job. Berg played sporadically until Frankie Pytlak, Cleveland’s starting catcher, injured himself, and Berg became the starting catcher.

Second trip to Japan

Herb Hunter arranged for a group of All-Stars, including Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Earl Averill, Charlie Gehringer, Jimmie Foxx and Lefty Gomez, to tour Japan playing exhibitions against a Japanese all-star team. Despite the fact that Berg was a mediocre, third-string catcher, he was invited at the last minute to make the trip. Among the items Berg took with him to Japan were a 16-mm Bell and Howell movie camera and a letter from MovietoneNews, a New York City newsreel production company with which Berg had contracted to film the sights of his trip. When the team arrived in Japan, he gave a welcome speech in Japanese and also addressed the legislature.

On November 29, 1934, while the rest of the team was playing in Omiya, Berg went to Saint Luke’s Hospital in Tsukiji, ostensibly to visit the daughter of American ambassador Joseph Grew. Instead, Berg sneaked onto the roof of the hospital, one of the tallest buildings in Tokyo, and filmed the city and harbor with his movie camera. He never did see the ambassador’s daughter. Back at home, the Indians gave him his unconditional release. Berg continued on to the Philippines, Korea and Moscow.

Late career and coaching (1935–1941)

After his return to America, Berg was picked up by the Boston Red Sox. In his five seasons with the Red Sox, Berg averaged fewer than 30 games a season.

On February 21, 1939, Berg made his first of three appearances on the radio quiz show, Information, Please! After missing the first question, Berg put on a dazzling performance. Of his appearance, baseball commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis told him, “Berg, in just thirty minutes you did more for baseball than I’ve done the entire time I’ve been commissioner”. On his third appearance, Clifton Fadiman, the moderator, started asking Berg too many personal questions. Berg did not answer any more questions and never appeared on the show again. Regular show guest and sportswriter John Kieran later said that “Moe was the most scholarly professional athlete (I) ever knew.”

After his playing career ended, Berg was a Red Sox coach in 1940 and 1941.

Post-baseball career

Spying for the U.S. Government

With the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese on December 7, 1941, the United States was thrust into World War II. To do his part for the war effort, Berg accepted a position with Nelson Rockefeller’s Office of Inter-American Affairs on January 5, 1942. Nine days later, his father, Bernard, died. During the summer of 1942, Berg screened the footage he shot of Tokyo Bay for intelligence officers of the United States military. The film may have helped Lieutenant Colonel Jimmy Doolittle plan his famous Doolittle Raid.

From August 1942 until February 1943, Berg was on assignment in the Caribbean and South America. His job was to monitor the health and physical fitness of the American troops stationed there. Berg, along with several other OIAA agents, left in June 1943 because they thought South America posed little threat to the United States, and they wanted to be someplace where their talents would be put to better use.

On August 2, 1943, Berg accepted a position with the Office of Strategic Services for a salary of $3,800 ($48,300 today) a year. He was a Paramilitary Operations Officer in the part of the OSS that is now called the Special Activities Division. In September, he was assigned to the Secret Intelligence branch of the OSS and given a place at the OSS Balkans desk. In this role, he parachuted into Yugoslavia to evaluate the various resistance groups operating against the Nazis to determine which was the strongest. He talked to both Draza Mihajlovic and Tito and reviewed their forces, deciding that Tito had the stronger and better supported group. His evaluations were used to help determine the amount of support and aid to give each group.[37] In late 1943, Berg was assigned to Project Larson, an OSS operation set up by OSS Chief of Special Projects John Shaheen. The stated purpose of the project was to kidnap Italian rocket and missile specialists out of Italy and bring them to the U.S. However, there was another project hidden within Larson, called Project AZUSA, with the goal of interviewing Italian physicists to see what they knew about Werner Heisenberg and Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker. It was similar in scope and mission to the Alsos project.

Moe turned down the Medal of Freedom during his lifetime; it was re-awarded after his death, with his sister accepting on his behalf.

From May 1944 to mid-December, Berg hopped around Europe interviewing physicists and trying to convince several to leave Europe and work in America. At the beginning of December, news about Heisenberg giving a lecture in Zurich, Switzerland reached the OSS, and Berg was assigned the task of attending the lecture and determining “if anything Heisenberg said convinced him the Germans were close to a bomb.” If Berg came to the conclusion that the Germans were close, he had orders to shoot Heisenberg; Berg determined that the Germans were not close. During his time in Switzerland, Berg became close friends with the physicist Paul Scherrer. Berg returned to the United States on April 25, 1945, and resigned from the Strategic Services Unit, the successor to the OSS, in August. He was awarded the Medal of Freedom on October 10, but he rejected the award on December 2. His sister later accepted it on his behalf after his death.

After World War II

In 1946, former Chicago White Sox teammate Ted Lyons was the new manager of the White Sox, and offered Berg a coaching position. Berg declined. Boston Red Sox owner Thomas Yawkey, who was much closer to Berg when he played for Red Sox, matched Lyons’ offer, but Berg still turned them down. Berg did not apply for a teaching position, or join a law firm.

In 1951, Berg begged the CIA to send him to Israel. “A Jew must do this,” he wrote in his notebook. The CIA rejected Berg’s request. Still, in 1952 Berg was hired by the CIA to use his old contacts from World War II to gather information about the Soviet atomic science. For the $10,000 plus expenses that Berg received, the CIA received nothing in return. The CIA officer who spoke with Berg when he returned from Europe said that he was “flaky”. Berg continued to serve his assignment for the CIA until 1954, when his contract expired. The CIA chose not to renew it. Berg tried again to serve the CIA and the CIA again declined.

For the next 20 years, Berg had no real job, living off friends and relatives who put up with him because of his charisma. When they would ask what he did for a living, he would reply by putting his finger to his lips, giving them the impression that he was still a spy. A life-long bachelor, he lived with his brother Samuel for 17 years. According to Samuel, he became moody and snappish after the war and did not seem to care for much in life besides his books. His brother finally grew fed up with the arrangement and asked Moe to leave and even had eviction papers drawn up. After being evicted from his brother’s home, Berg moved in with his sister Ethel in Belleville, New Jersey, where he remained for the rest of his life.

He received a handful of votes in Baseball Hall of Fame voting (four in 1958, and five in 1960). When he was criticized for “wasting” his intellectual talent on the sport he loved, Berg replied, “I’d rather be a ballplayer than a justice on the U.S. Supreme Court”.

Berg received many requests to write his memoirs, but turned them down; he almost wrote them in 1960, but he quit after the co-writer assigned to him confused him with Moe Howard of the Three Stooges.

Death

Moe Berg died on May 29, 1972, at age 70, from injuries sustained in a fall at home. A nurse at the Newark, New Jersey hospital where he died recalled his final words as, “How did the Mets do today?” (They won.) His remains were cremated and spread over Mount Scopus in Israel.

Legacy

Berg was inducted into the National Jewish Sports Hall of Fame in 1996, and the Baseball Reliquary’s Shrine of the Eternals in 2000. His is the only baseball card on display at the headquarters of the Central Intelligence Agency.

In 1976, reporters Louis Kaufman of the Boston Globe and Tom Sewell of the Boston Herald joined writer Barbara Fitzgerald to write Moe Berg: Athlete, Scholar, Spy. In 1994 Nicholas Dawidoff wrote a biography, The Catcher Was a Spy: The Mysterious Life of Moe Berg.

Chuck Brodsky, an American singer-songwriter, released a song entitled “Moe Berg: The Song” on his 1998 album Radio.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IGp1c3QgY2xpY2sgdGhlIHRhZ3MhICAiLCJhZnRlciI6IiIsImxpbmtfdG9fdGVybV9wYWdlIjoib24iLCJzZXBhcmF0b3IiOiIgfCAiLCJjYXRlZ29yeV90eXBlIjoicG9zdF90YWcifX0=@