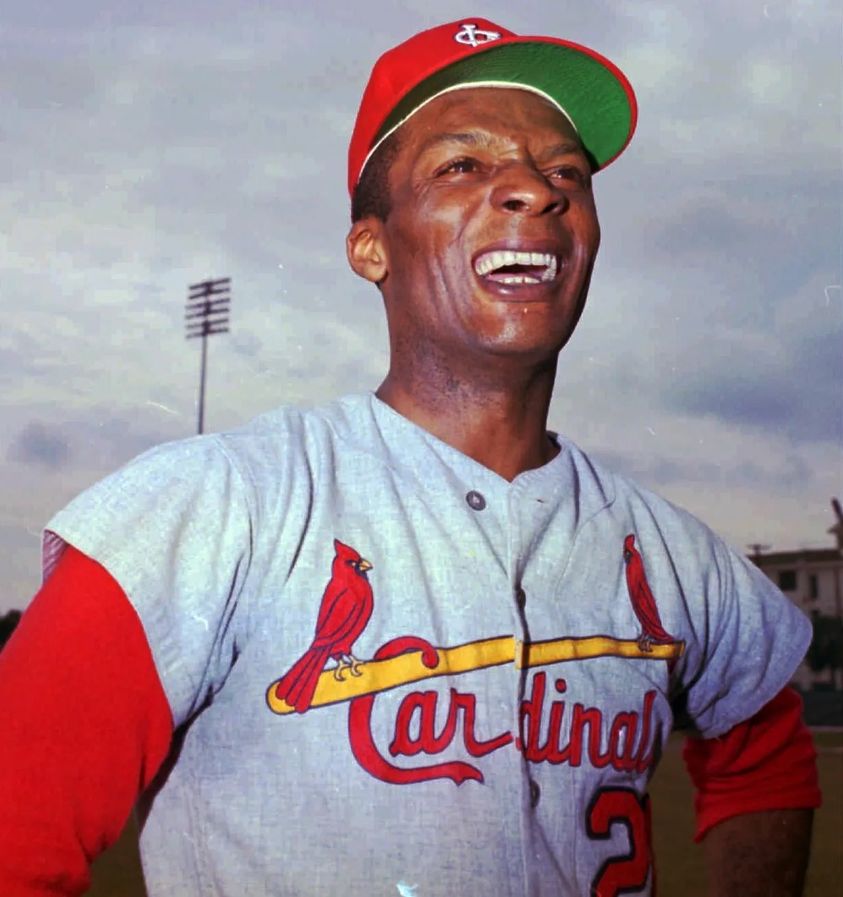

Curt Flood

Positions: Outfield

Bats: R Throws: R

Height: 5′ – 9″ Weight: 165

Born: Tuesday, January 18, 1938 in Houston, TX USA

Died: January 20, 1997 in Los Angeles, CA USA

Debut: September 9, 1956

Last Game: April 25, 1971

Full Name: Curtis Charles Flood

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1956

Frank Robinson

Luis Aparicio

Bill Mazeroski

Curt Flood

Don Drysdale

Moe Drabowsky

Tito Francona

Charlie Lau

Whitey Herzog

Notable Events and Chronology for Curt Flood Career

“He was a man who dared to live by the strength of his conviction. Most of us were not courageous enough to take that stand. I know I wasn’t.” – Maury Wills

Flood had a marvelous career that will always be marred by his misjudging of a fly ball in the seventh game of the 1968 World Series, and his suit against baseball that eventually led to free agency. The 5’9″ Houston native played just eight games with Cincinnati before beginning his stellar 12-year stay with St. Louis in 1958. In 1964 he led the NL with 211 hits. He batted a career-high .335 in 1967. In an act that Flood felt was “impersonal,” the Cardinals traded him, Tim McCarver, Byron Browne, and Joe Hoerner to the Phillies on October 7, 1969, for slugger Dick Allen, Cookie Rojas, and Jerry Johnson. Flood balked at his trade to Philadelphia, which had a poor team and played its games in an old stadium, before usually belligerent fans in 1969.

Flood fought the reserve clause. He first asked Commissioner Kuhn to declare him a free agent, and was denied. He filed suit on January 16, 1970, stating that baseball had violated the nation’s anti-trust laws. Even though he was making $90,000 at the time, Flood likened “being owned” to “being a slave 100 years ago.” The case went to the Supreme Court, with former Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg pressing his case. Goldberg agreed to work for expenses, which totaled nearly $200,000, before judgment was finally rendered. The Supreme Court upheld the District Court and Court of Appeals rulings favoring organized baseball. Flood sat out 1970, but signed with the Senators in 1971 for $110,000. To get the rights to Flood, who was still bound by the reserve clause, Washington had to part with marginal players Greg Goossen, Jerry Terpko, and Gene Martin, none of whom would ever appear with Philadelphia. Flood played 13 games for Washington, hit a paltry .200, and retired in April. He later spent the 1978 season in the A’s broadcasting booth with Bud Foster.

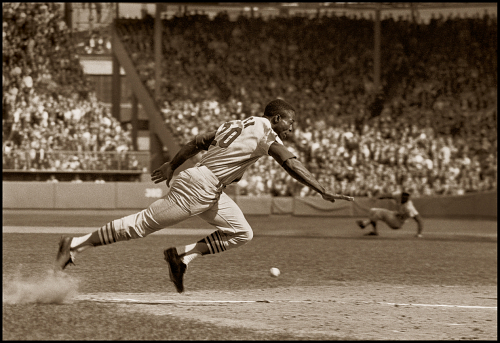

Playing career

Born in Houston, Texas and raised in Oakland, California, Flood played in the same high school outfield as Vada Pinson and Frank Robinson. Flood signed with the Cincinnati Redlegs in 1956, and made a handful of appearances for the team in 1956–57 before being traded to the Cardinals in December 1957. For the next twelve seasons he became a fixture in center field for St. Louis; although he struggled at the plate from 1958–1960, his defensive skill was apparent. He had his breakthrough year after Johnny Keane took over as manager in 1961, batting .322, and followed by hitting .296 in 1962 with 12 home runs. He continued to improve offensively in 1963, hitting .302 and scoring a career-high 112 runs, third most in the NL; he also had career bests in doubles (34), triples (9) and stolen bases (17), and collected 200 hits in an NL-leading 662 at bats. In that year he received the first of his seven consecutive Gold Gloves.

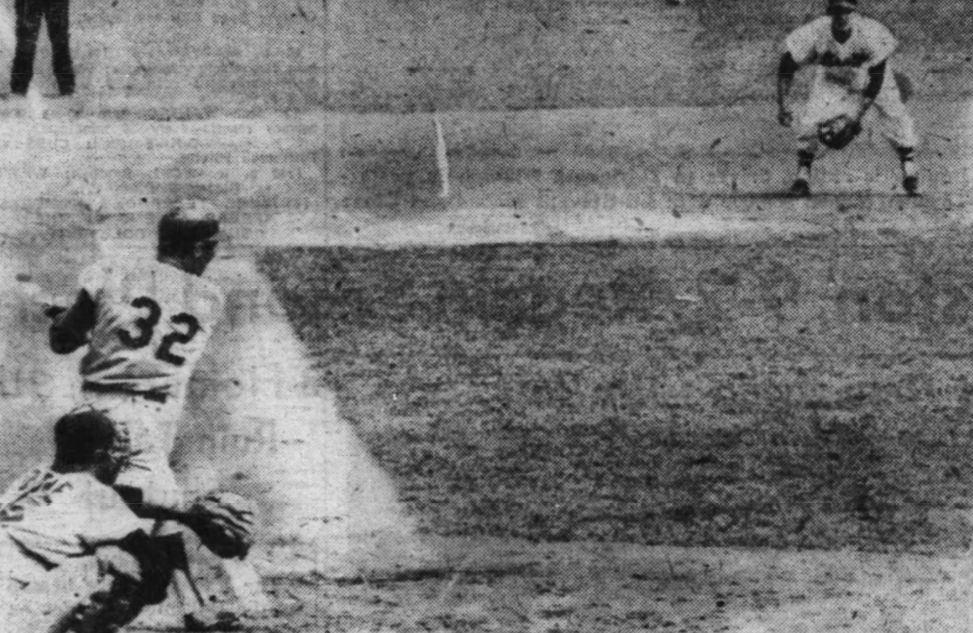

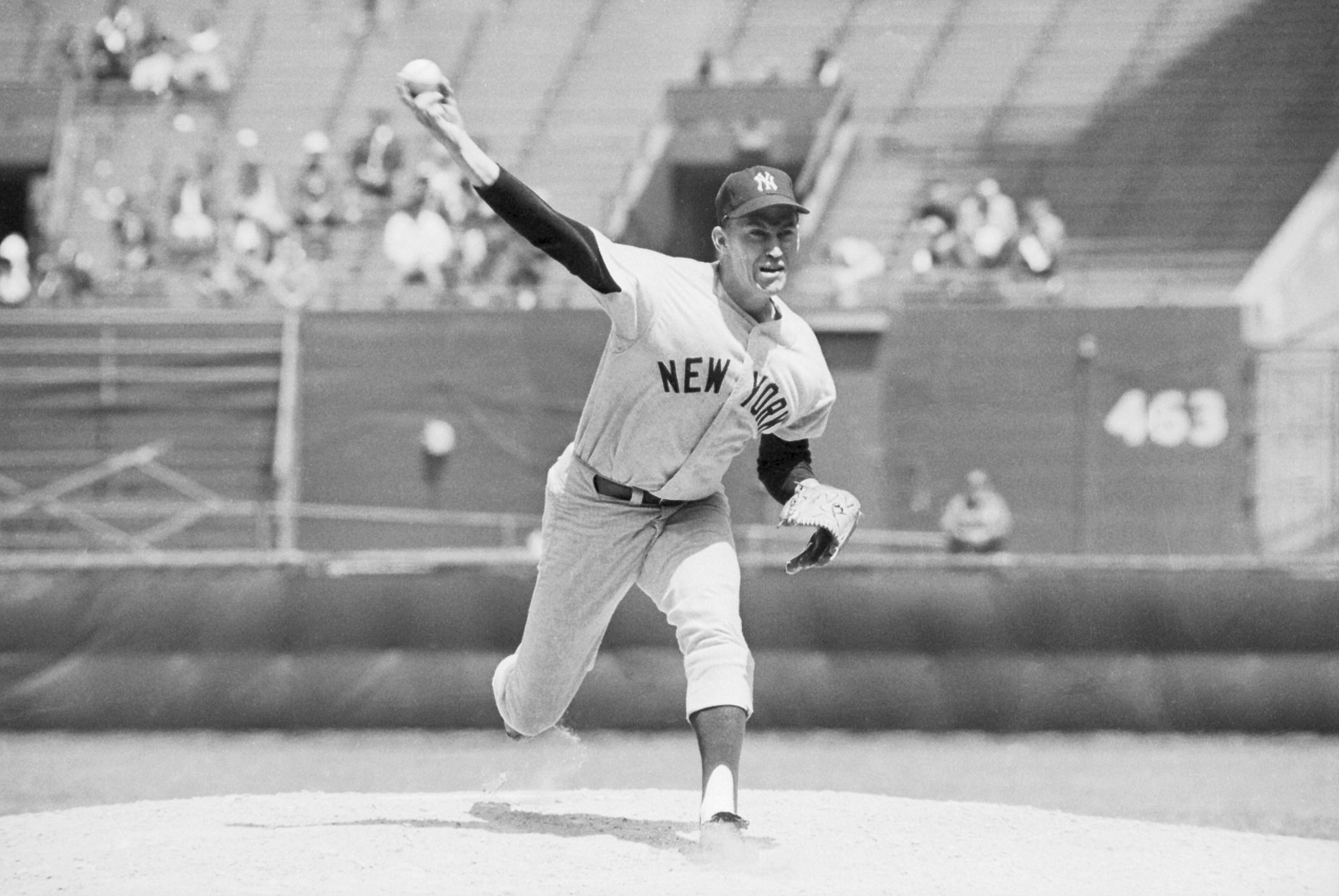

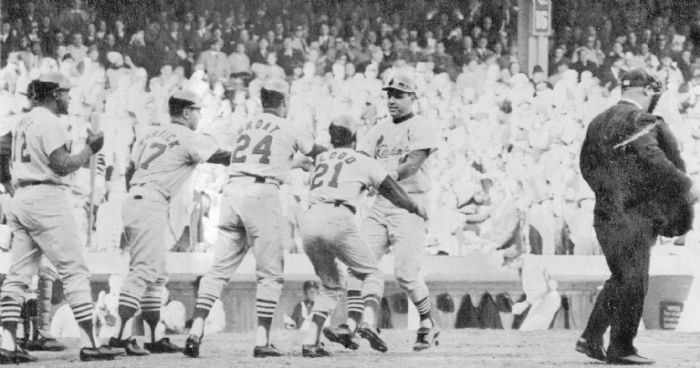

He earned his first All-Star selection in 1964 while leading the NL in hits and batting .311. His 679 at bats led the NL again and were the fifth highest total in league history to that point, setting a team record by surpassing Taylor Douthit’s 1930 total of 664; Lou Brock broke the team record three years later with 689. He also had a league-leading 211 hits. Batting leadoff in the 1964 World Series against the New York Yankees, he hit only .200 but scored in three of the Cardinal victories as the team won in seven games for its first championship since 1946. In 1965 Flood had his greatest power output, with 11 home runs and 83 runs batted in while hitting .310. He made the All-Star team again in 1966, a season in which he did not commit an error in the outfield; his record errorless streaks of 226 games (NL record) and 568 total chances (major league record) ran from September 3, 1965 to June 4, 1967.

In 1967 he had his highest batting mark with a .335 average, though his other batting totals fell off from previous years, in helping the Cardinals to another championship. In the 1967 World Series against the Boston Red Sox he hit a woeful .179, but made some crucial contributions. In Game 1, he advanced Brock to third base twice, putting him in position to score both runs in a 2–1 victory; in Game 3, he drove in Brock with the first run of a 5–2 win. As team co-captain (with Tim McCarver) in 1968 he had perhaps his best year, earning his third All-Star selection and finishing fourth in the MVP balloting (won by teammate Bob Gibson) on the strength of a .301 batting average and 186 base hits. Against the San Francisco Giants that year, Flood was involved in the final outs of the first back-to-back no-hitters in Major League history. On September 17 he struck out for the final out of Gaylord Perry’s 1-0 gem. The next day, he caught Willie McCovey’s fly ball for the final out of Ray Washburn’s 2-0 no-hitter. Had he not notably misjudged a Jim Northrup fly ball (ruled a triple) with two out in the seventh inning of Game 7 of the 1968 World Series against the Detroit Tigers, the Cardinals might have won their third championship of the decade; Detroit scored twice on the play, with Northrup later coming in for a 3-0 lead, and won the game 4-1. Up to that point Flood had been enjoying the best Series of his career, despite dealing with personal problems at home, hitting .286 with three steals.

In 1969, despite the lower pitching mound instituted that season which saw a general rise in batting average league wide, Flood’s batting average slipped to .285. His brother was arrested during the season, and he participated in a couple of public confrontations with Cardinals’ management. Early in the season his conflict with the Cardinals involved his desire for a $100,000 salary. Late in the season he publicly criticized the team for reorganizing the team before they were officially eliminated. He received his seventh Gold Glove this season, just as other events in his career began to affect the entire sport.

Flood collected the first hit in a Major League regular season game in Canada. He doubled off Montreal Expos pitcher Larry Jaster in the first inning of the Expos’ inaugural home game, on April 14, 1969 at Jarry Park. (Jaster, a Cardinal teammate of Flood’s just the year before, had been selected by the Expos in the expansion draft.)

Challenge of the reserve clause

Despite his outstanding playing career, Flood’s principal legacy developed off the field. He believed that Major League Baseball’s decades-old reserve clause was unfair in that it kept players beholden for life to the team with whom they originally signed, even when they had satisfied the terms and conditions of those contracts.

On October 7, 1969, the Cardinals traded Flood, catcher Tim McCarver, outfielder Byron Browne, and left-handed pitcher Joe Hoerner to the Philadelphia Phillies for first baseman Dick Allen, second baseman Cookie Rojas, and right-handed pitcher Jerry Johnson. However, Flood refused to report to the moribund Phillies, citing the team’s poor record and the fact that they played in dilapidated Connie Mack Stadium before belligerent – and, racist – fans. Some reports say he was also irritated that he had learned of the trade from a reporter, but Flood’s autobiography says he learned of the trade from mid-level Cardinals management and he was angry that the call did not come from the general manager. He forfeited a lucrative $100,000 ($565,606 as of 2011), contract by his refusal to be traded, and consulted with players’ union head Marvin Miller. He also met with Phillies general manager John Quinn, who left the meeting with the belief that he had convinced Flood to report to the team. After being advised that the union was prepared to pay the costs of the lawsuit, he chose to proceed.

In a letter to Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn, Flood demanded that the commissioner declare him a free agent:

December 24, 1969

After twelve years in the major leagues, I do not feel I am a piece of property to be bought and sold irrespective of my wishes. I believe that any system which produces that result violates my basic rights as a citizen and is inconsistent with the laws of the United States and of the several States.

It is my desire to play baseball in 1970, and I am capable of playing. I have received a contract offer from the Philadelphia club, but I believe I have the right to consider offers from other clubs before making any decision. I, therefore, request that you make known to all Major League clubs my feelings in this matter, and advise them of my availability for the 1970 season.

Flood was influenced by the events of the 1960s that took place in the United States. According to Marvin Miller, Flood told the executive board of the players’ union, “I think the change in black consciousness in recent years has made me more sensitive to injustice in every area of my life.” However, he added that he was doing in challenging the reserve clause was primarily as a major league ballplayer.

Flood v. Kuhn

Commissioner Kuhn denied his request, citing the propriety of the reserve clause and its inclusion in Flood’s 1969 contract. In response, Flood filed a $1 million lawsuit (which would be automatically tripled under the Sherman Act) against Kuhn and Major League Baseball on January 16, 1970, alleging that Major League Baseball had violated federal antitrust laws. Even though Flood was making $90,000 at the time, he likened the reserve clause to slavery; it was a controversial analogy, even among those who opposed the reserve clause. Among those testifying on his behalf were former players Jackie Robinson and Hank Greenberg, and former owner Bill Veeck; no active players testified, nor did any attend the trial. Although the player representatives had voted unanimously to support the suit, rank-and-file players were strongly divided, with many fervently supporting the management position.

The case, Flood v. Kuhn (407 U.S. 258), eventually went to the Supreme Court. Flood’s attorney, former Supreme Court Justice Arthur Goldberg, asserted that the reserve clause depressed wages and limited players to one team for life. Major League Baseball’s counsel countered that Commissioner Kuhn acted in the way he did “for the good of the game.”

Ultimately, the Supreme Court, acting on stare decisis “to stand by things decided”, ruled 5–3 in favor of Major League Baseball, upholding a 1922 ruling in the case of Federal Baseball Club v. National League (259 U.S. 200). Justice Lewis Powell did not participate in the case due to his ownership of stock in Anheuser-Busch, which owned the Cardinals.

Aftermath and post-baseball life

Flood sat out the entire 1970 season. Eventually, the Cardinals were forced to give up two minor leaguers to the Phillies in compensation for Flood’s refusal to report, one of whom – center fielder Willie Montañez – went on to have a 14-year career. Meanwhile, in November 1970 Flood was sent by the Phillies to the Washington Senators in a five-player trade, and signed a $110,000 contract with Washington. He ended his career with 13 games for the Senators in 1971, in which he batted only .200 and had lackluster play in center field. Former teammate Gibson later wrote that Flood once returned to his locker to find a funeral wreath on it. Despite manager Ted Williams’ vote of confidence, Flood retired. He had a lifetime batting average of .293 with 1861 hits, 85 home runs, 851 runs and 636 RBI.

Later that year, Flood wrote an apologetic and defensive autobiography entitled The Way It Is. He also indulged in his love of painting. Ultimately, the reserve clause was struck down in 1975, when arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled that since pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally played for one season without a contract, they could become free agents. This decision essentially dismantled the reserve clause and opened the door to widespread free agency. Seitz’s decision was based on the vague wording of the reserve clause in the standard players’ contract, and Flood’s unsuccessful challenge had little or no bearing on the ruling.

Shortly after his retirement, Flood owned a bar in the Spanish resort town of Palma de Mallorca where he moved to escape from bankruptcy of his Curt Flood Associates business, from two lawsuits, and from an IRS lien on a home he bought for his mother. He eventually returned to baseball as part of the Oakland Athletics’ broadcasting team in 1978. He was also the commissioner of the short-lived Senior Professional Baseball Association in 1988.

In his spare time, Flood painted. His 1989 oil portrait of Joe DiMaggio sold at auction for $9,500.

Flood remained involved with efforts in trying to reduce the power of MLB team owners. In the mid 1990’s, Flood became involved in the management group of the United Baseball League (UBL). The UBL was an attempt to create a smaller alternative to MLB. The UBL had a long term TV contract with Liberty Media but the deal fell through when Fox Sports, who had a contract with MLB, merged with Liberty Media.

Flood stopped smoking in 1979, and drinking in 1986, despite having been a heavy drinker and smoker for years. Diagnosed with throat cancer in 1995, Flood was originally given a 90% chance of survival, but Flood died in Los Angeles, California at his home. Flood was survived by his five children, Debbie, Gary, Shelly, Scott and Curt Flood Jr., a wife, actress Judy Pace and her two daughters. Flood was interred in Inglewood Park Cemetery, Inglewood California.

His legacy was remembered in Congress via a bill, the Baseball Fans and Communities Protection Act of 1997; numbered HR 21 (Flood’s Cardinals uniform number) and introduced on the first day of the 105th Congress in 1997 by Rep. John Conyers, Jr. (D-Michigan), removing baseball’s controversial antitrust exemption with regards to labor. Sen. Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) introduced similar legislation in the Senate that year, called the Curt Flood Act of 1998 (SB 53).

Curt Flood is also a non-participating but pivotal character in the book Our Gang by Philip Roth.

Curt Flood on Vada Pinson:

So far, he has tolerated the chemotherapy; the second cycle began Monday. But now Curt Flood is to undergo radiation for throat cancer Thursday morning, and the doctors say he cannot skip the treatment.

So Curt Flood hopes his friend of 50 years, Vada Pinson, will understand if he is unable to make it to Oakland for Pinson’s funeral that day.

“Vada would say, `You did what? Get out of here,’” Flood said Tuesday from his home in Los Angeles, where he looks up from the phone and every day sees the same picture on the wall: Vada Pinson, Curt Flood and Lou Brock on a framed cover of the Sporting News.

“I’ve seen that handsome face for many years,” Flood said. “Vada was neat as a pin. He shined his shoes between innings, almost.”

The picture was taken in 1969, when the three were together in the outfield of the St. Louis Cardinals. “The doctors say they caught it in time,” Flood said of the cancer. “The prognosis is good. They say it’s 90 to 95 percent curable. I haven’t been sick. I haven’t lost my hair … or my testiness.

“Yes, it’s scary. It’s something God puts on your shoulders: `Here, handle this.”‘ Last winter, when Flood was inducted into the Bay Area Hall of Fame, his presenter was Vada Pinson, who drove all the way from South Florida. The scheduled inductee this winter: Pinson. Of course, you know who Pinson asked to present him.

“I’m going to ask them to honor his last wish,” Flood said Tuesday. “My lasting image of Vada: I always remember Vada Pinson’s smile. It was always present. If not on his face, it was in his voice.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Cincinnati Reds (1956-1957)

St. Louis Cardinals (1958-1969)

Washington Senators (1971)

Awards and Honors

1963 NL Gold Glove

1964 NL Gold Glove

1965 NL Gold Glove

1966 NL Gold Glove

1967 NL Gold Glove

1968 NL Gold Glove

1969 NL Gold Glove

Post-Season Appearances

1964 World Series

1967 World Series

1968 World Series

Hitting Streaks

19 games (1969)

19 games (1969)

17 games (1962)

17 games (1962)

15 games (1965)

15 games (1965)

All-Star Selections

1964 NL

1966 NL

1968 NL

Other Resources & Links