Frank Robinson Stats & Facts

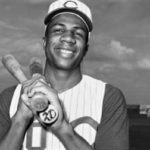

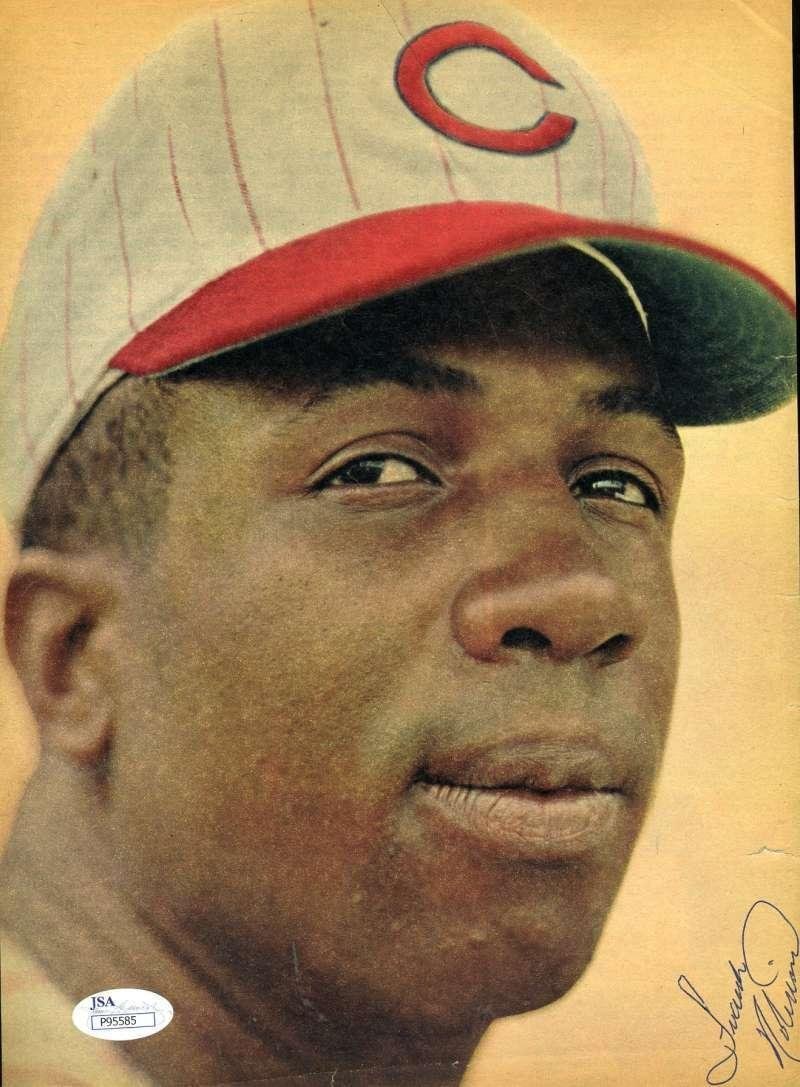

Frank Robinson

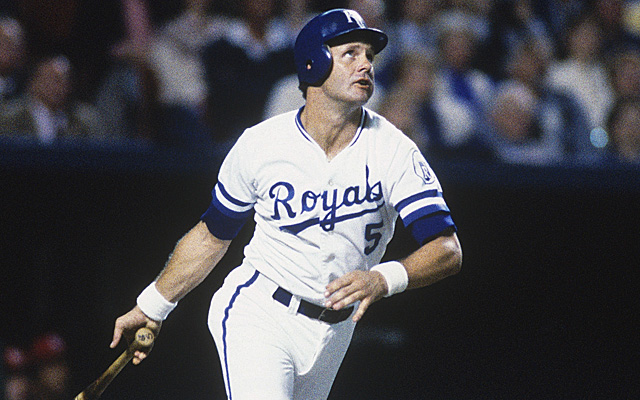

Positions: Outfielder and First Baseman

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-1, 183lb (185cm, 83kg)

Born: August 31, 1935 in Beaumont, TX

Died: February 7, 2019 in Los Angeles, CA

High School: McClymonds HS (Oakland, CA)

School: Xavier University (Cincinnati, OH)

Debut: April 17, 1956 (8,933rd in MLB history)

vs. STL 3 AB, 2 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 18, 1976

vs. BAL 1 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1982. (Voted by BBWAA on 370/415 ballots)

View Frank Robinson’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Frank Robinson

Nicknames: The Judge or Pencils

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1956

Frank Robinson

Luis Aparicio

Bill Mazeroski

Curt Flood

Don Drysdale

Moe Drabowsky

Tito Francona

Charlie Lau

Whitey Herzog

The Frank Robinson Teammate Team

C: Alan Ashby

1B: Tony Perez

2B: Pete Rose

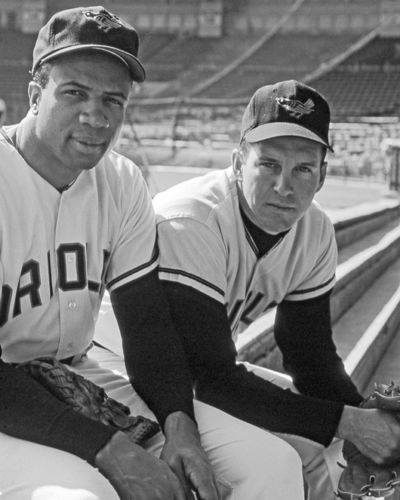

3B: Brooks Robinson

SS: Leo Cardenas

LF: Willie Davis

CF: Vada Pinson

RF: Paul Blair

DH: Rico Carty

SP: Jim Palmer

SP: Dave McNally

SP: Don Sutton

SP: Nolan Ryan

SP: Gaylord Perry

RP: Dennis Eckersley

M: Earl Weaver

Notable Events and Chronology for Frank Robinson Career

Biography Frank Robinson

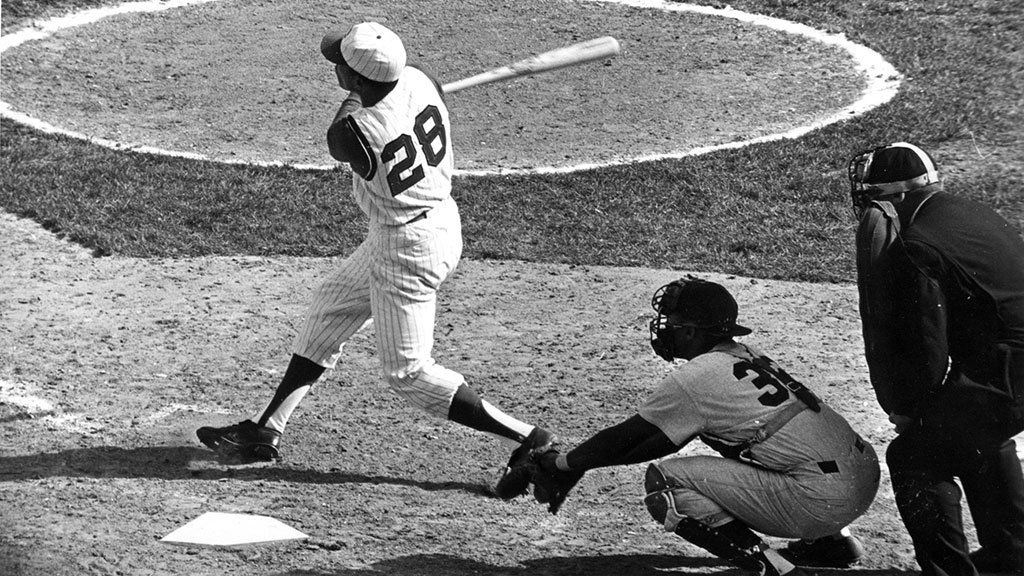

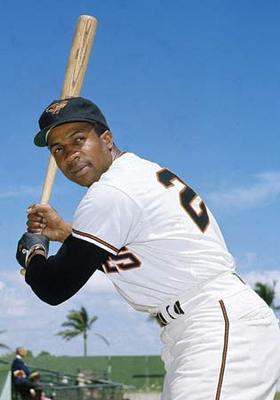

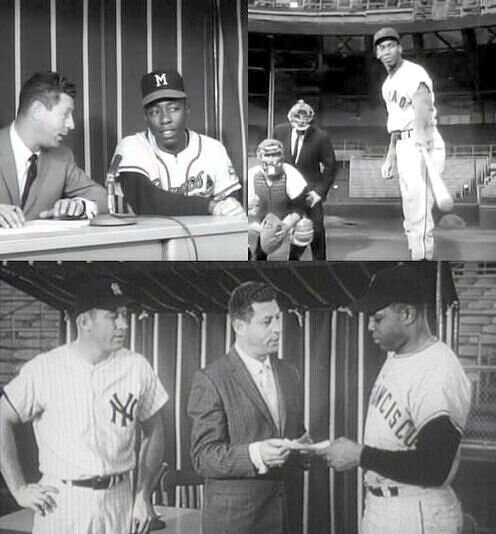

After Major League Baseball announced its All-Century Team in 1999, Tommy Lasorda stated emphatically that “it was a joke that Frank Robinson wasn’t on it.” Although Lasorda certainly could not be faulted for feeling as he did, the omission of Robinson from that prestigious club really should not have come as a surprise to anyone. Despite accomplishing some truly amazing things on the ballfield during his career, while simultaneously posting some of the most impressive numbers in baseball history, Robinson never received the acclaim he deserved for being one of the greatest players in the history of the game. The fact that the Hall of Fame outfielder spent his peak years playing in the relatively small media markets of Cincinnati and Baltimore undoubtedly is at least partly responsible for the lack of recognition he received throughout his career. Robinson’s lack of notoriety could also be attributed to the fact that he was often overlooked in favor of some of his more colorful contemporaries. Robinson didn’t have the raw power of Mickey Mantle. Nor did he possess the charisma of Willie Mays. He didn’t play the outfield with the sheer abandon of Roberto Clemente. And, unlike Hank Aaron, he didn’t hit 40 home runs practically every year. Nevertheless, Robinson won two Most Valuable Player Awards and a triple crown, led his teams to five pennants and two world championships, and ended his career fourth on the all-time home-run list, behind only Aaron, Mays, and Babe Ruth.

Frank Robinson Jr. was born in Beaumont, Texas on August 31, 1935, the youngest of ten children in what was essentially a single-parent household. Robinson’s father, who made his living as a railroad worker, deserted the family when Frank was just an infant. As a result, Robinson’s mother, whose previous two marriages produced her nine other offspring, was left the unenviable task of trying to provide the basic necessities for her children by herself. After finding it difficult to make ends meet in Texas, Robinson’s mother moved to California with four-year-old Frank and his two half-brothers, eventually settling in the Oakland area. The Robinsons lived in a poor, ethnically-diverse neighborhood that helped to shape the youngest Robinson’s tough, single-minded nature.

Robinson later told Sports Illustrated, “I never really knew my own father. But it didn’t bother me. My mother, my brothers and sisters. I was always right in the middle of a bunch of bigger boys, and they’d rough me up and give me information. They were always keeping my feet on the ground, making me see the outlook from other sides.”

Robinson spent most of his free time playing baseball on the sandlots of West Oakland, where he began planning ahead for a career as a professional baseball player. He went on to attend McClymonds High School, whose program also developed future major league All-Star outfielders Vada Pinson and Curt Flood. In addition to playing third base and the outfield at McClymonds, Robinson starred on the basketball team, which also featured future NBA Hall of Famer Bill Russell.

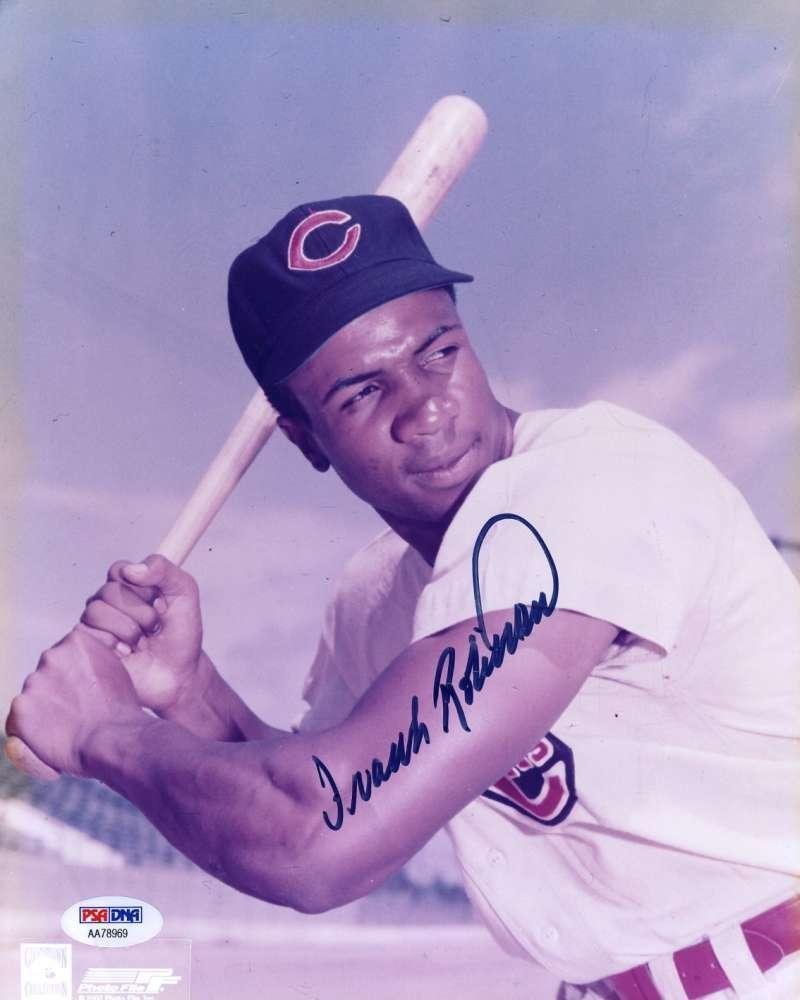

After graduating from high school in 1953, Robinson quickly signed with the Cincinnati Reds for a $3,500 bonus. Assigned to Cincinnati’s Class C team in Ogden, Utah for the 1953 campaign, the California-raised Robinson had a difficult time coping with the town’s heavily-segregated racial policies. Nonetheless, he shined on the field, starting out at third base before requesting a shift to the outfield.

Robinson encountered increased racial hostilities the following year after he was promoted to the South Atlantic League. Fans in the circuit’s southern-based states often hurled racial epithets at the 19-year-old outfielder, who later admitted he once considered going after one particular spectator in the stands with a baseball bat. After experiencing two years of such treatment, Robinson arrived in Cincinnati in the spring of 1956, in his own words “quiet and withdrawn,” both afraid and unwilling to associate with his teammates.

Robinson took out any inward animosity he may have had on opposing pitchers. Playing primarily left field in his first year with the Reds, the righthanded hitting Robinson tied Wally Berger’s rookie record of 38 home runs, while also knocking in 83 runs, batting .290, and leading the league with 122 runs scored. Robinson’s outstanding performance earned him his first All-Star Game nomination, N.L. Rookie of the Year honors, and a seventh-place finish in the league MVP voting.

Robinson continued to play well in each of the next two seasons, while splitting his time between left field, center field, first base, and third base. After finishing among the league leaders with 29 home runs, 97 runs scored, and a .322 batting average in 1957, he placed near the top of the league rankings with 31 homers and 90 runs scored the following year, while also earning a Gold Glove for his outstanding play in the outfield.

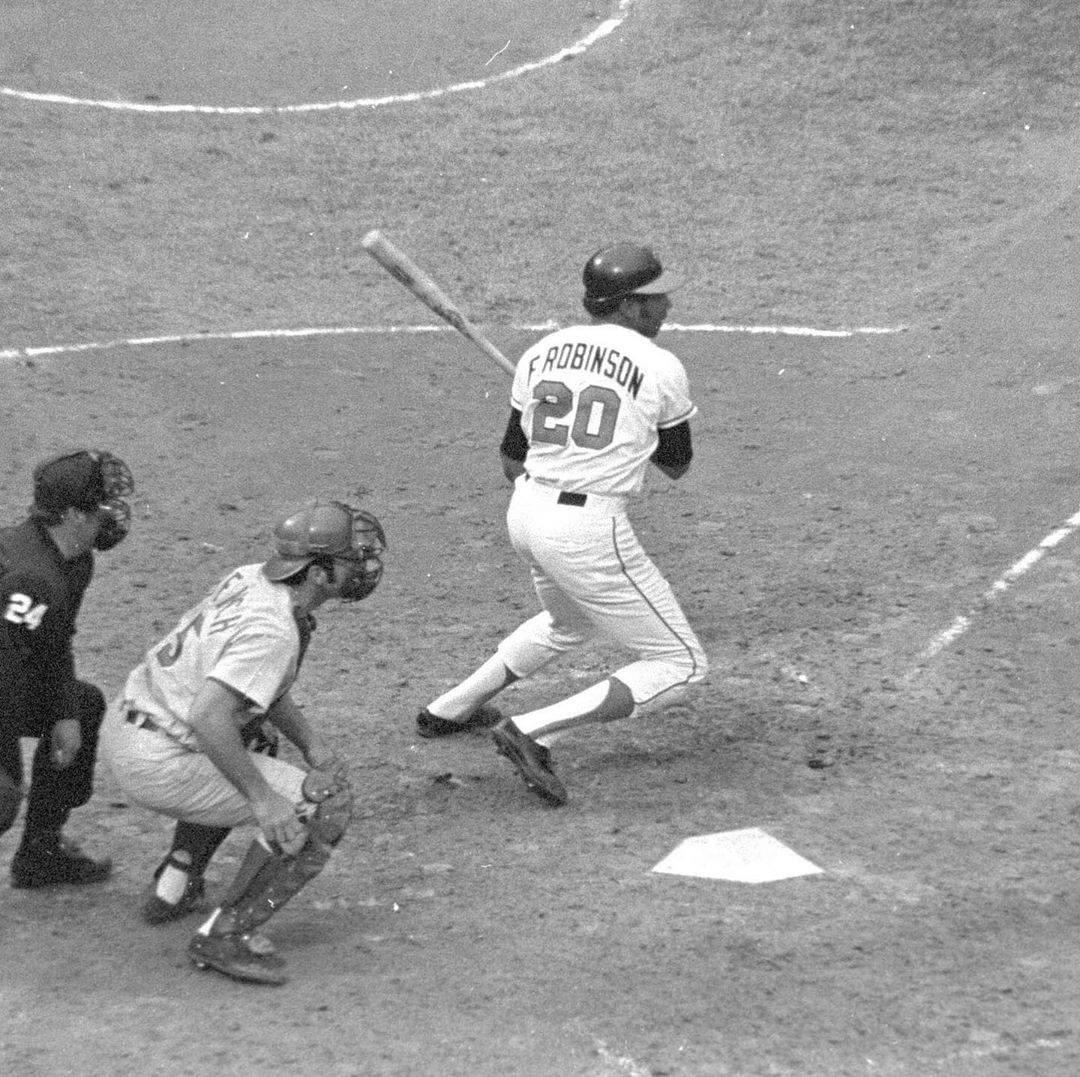

Robinson took his game to the next level in 1959, after being shifted to first base prior to the start of the campaign. The 24-year-old slugger finished among the league leaders in nine different offensive categories, including home runs (36), runs batted in (125), runs scored (106), and batting average (.311). The 6’1″, 185-pound Robinson exhibited exceptional power at the plate despite his relatively lean frame. Deceptively strong and quick-wristed, Robinson drove the ball with power to all fields while daring opposing pitchers to hit him by standing extremely close to home plate and leaning forward in the batter’s box. Explaining the attitude he took with him to home plate, Robinson said,

“Pitchers did me a favor when they knocked me down. It made me more determined. I wouldn’t let that pitcher get me out. They say you can’t hit if you’re on your back, but I didn’t hit on my back. I got up.”

Robinson also employed a hard-nosed style on the basepaths, testing the courage of opposing infielders by sliding hard into each base and going into second base harder than perhaps any other player in baseball when breaking up the double play. He described the philosophy he used while running the bases by saying, “The baselines belongs to the runner, and whenever I was running the bases, I always slid hard. I wanted infielders to have that instant’s hesitation about coming across the bag at second or about standing in there awaiting a throw to make a tag. There are only 27 outs in a ballgame, and it was my job to save one for my team every time I possibly could.”

Robinson’s aggressive style of play led to one of the more memorable brawls in baseball history in 1959. During the first game of a doubleheader played against the Braves in Milwaukee, Robinson attempted to knock the ball out of the glove of Braves third baseman Eddie Mathews on his way back to the bag. After applying the tag to Robinson, an enraged Mathews lunged at the Cincinnati slugger, delivering several blows to his forehead and blackening both eyes. Although Robinson lost that particular battle, he gained a measure of revenge in the nightcap, delivering a grand slam during the Reds’ victory and silencing the Milwaukee fans who spent the entire game voicing their displeasure towards him. Mathews later expressed his admiration for Robinson by saying in the next day’s newspaper, “That’s the way to get even.”

Splitting his time once more between first base and the outfield in 1960, Robinson won the first of three straight National League slugging titles, with a mark of .595. Undeterred by a series of death threats he received as a result of his well-publicized advocacy of civil rights, Robinson also hit 31 homers and batted .297. In response to the threats made on his life, Robinson began carrying around a gun in self-defense. He was arrested at one point during the season for displaying it to a short-order cook who had refused to serve him.

In spite of any off-field distractions Robinson endured during his time in Cincinnati, his aggressive style of play eventually enabled him to establish himself as the Reds’ team leader. After being shifted back to the outfield in 1961, Robinson led his team to the National League pennant by placing among the league leaders with 37 home runs, 124 runs batted in, 117 runs scored, a .323 batting average, and a .404 on-base percentage. He also topped the circuit with a .611 slugging percentage and an 88 percent stolen base percentage (22 steals in 25 attempts), en route to earning league MVP honors.

Robinson followed up his MVP season with another spectacular campaign in 1962. In addition to leading the league with 134 runs scored, 51 doubles, a .421 on-base percentage, and a .624 slugging percentage, Robinson hit 39 home runs and established new career highs with 136 runs batted in, 208 hits, and a .342 batting average. He finished fourth in the league MVP balloting.

After a subpar 1963 season, Robinson performed exceptionally well in each of the next two years, combining for 62 homers, 209 RBIs, and 212 runs scored, while batting near the .300-mark both times. Yet, claiming that Robinson was “an old 30,” Reds GM Bill DeWitt traded his best player to the Baltimore Orioles at the conclusion of the 1965 campaign for pitchers Milt Pappas and Jack Baldschun, in what turned out to be one of the most lopsided deals in baseball history. Although Robinson didn’t say anything at the time, he knew that DeWitt’s real motive for trading him away was that the GM no longer wished to interact with someone so outspoken, especially if that someone happened to be a black man.

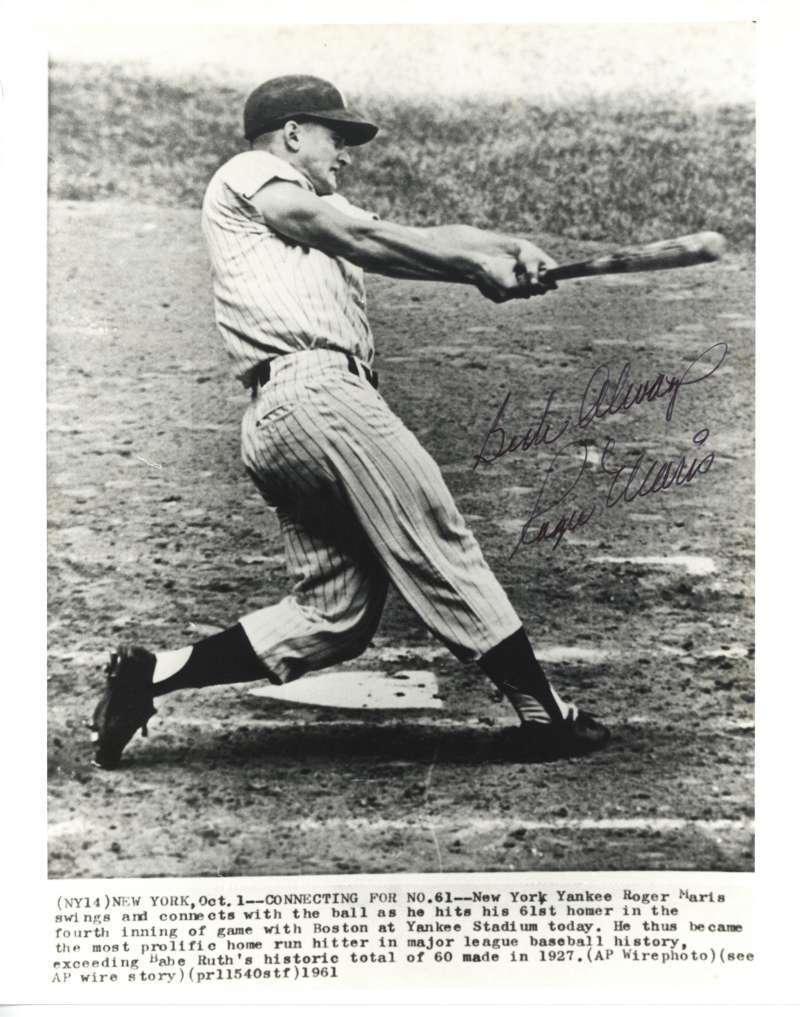

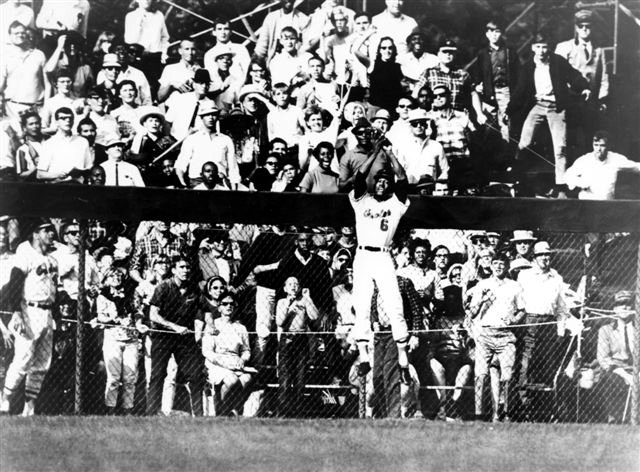

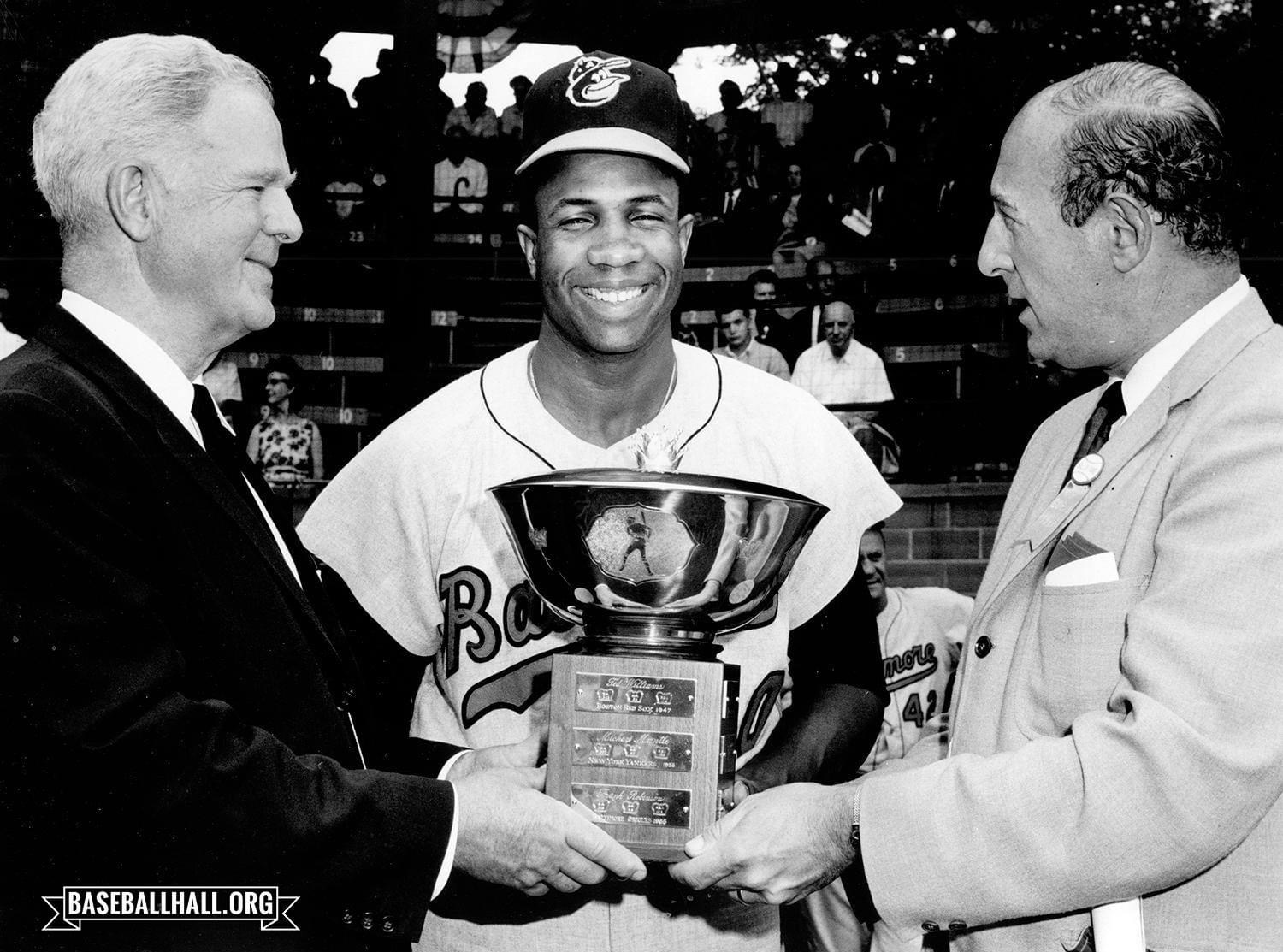

Robinson voiced any objections he may have had to DeWitt’s remarks by capturing the American League triple crown in 1966, en route to winning league MVP honors and leading the Orioles to the American League pennant. By being named A.L. MVP, Robinson became the first player to win the award in each league. In addition to topping the circuit with 49 home runs, 122 runs batted in, and a .316 batting average, the Baltimore right fielder also finished first with 122 runs scored, 367 total bases, a .410 on-base percentage, and a .637 slugging percentage. However, Robinson contributed more than just numbers to the Orioles. Bringing his aggressive baserunning and outstanding leadership skills with him to Baltimore, Robinson completely changed the culture of the team. He inspired confidence in his teammates and forced them to be accountable to each other by introducing them to the “kangaroo court,” over which he presided. He then capped off his brilliant year by leading the Orioles to a four-game sweep of the Dodgers in the World Series. Robinson hit two game-winning home runs during the Fall Classic to earn Series MVP honors.

Injuries hampered Robinson in each of the next two seasons, but he put up solid numbers in 1967 (30 home runs, 94 RBIs, .311 AVG), before slumping badly in 1968. Back in top form in 1969, Robinson led the Orioles to the first of three straight American League pennants by hitting 32 homers, driving in 100 runs, scoring 111 others, and batting .308. After losing the 1969 World Series to the underdog New York Mets, Baltimore defeated Robinson’s old team – the Cincinnati Reds – in the following year’s Fall Classic, with the rightfielder gaining a measure of revenge by hitting two home runs and knocking in four runs in the five games played.

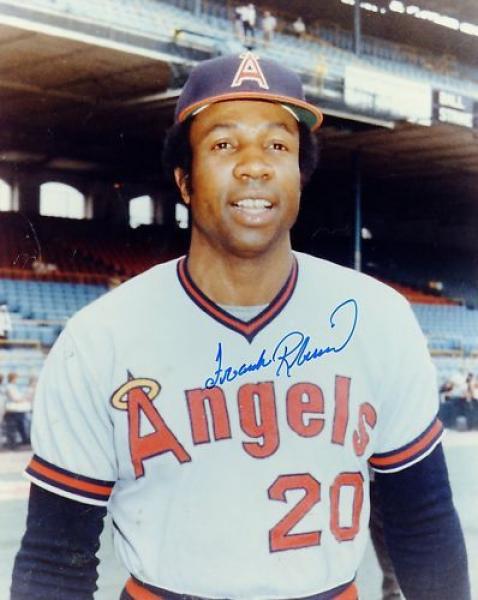

Although Robinson performed well in both 1970 and 1971, he continued to see his playing time gradually diminish each year due to several nagging injuries and the desire of management to insert hard-hitting young outfielder Merv Rettenmund into the starting lineup more regularly. After hitting 28 home runs and driving in 99 runs in 133 games in 1971, Robinson was traded to the Dodgers at the end of the year as part of a six-man deal. He spent only one season in Los Angeles, before being dealt to the California Angels at the conclusion of the 1972 campaign. Robinson spent most of the next two seasons with the Angels, but he was claimed on waivers by the Cleveland Indians after being released by California late in 1974.

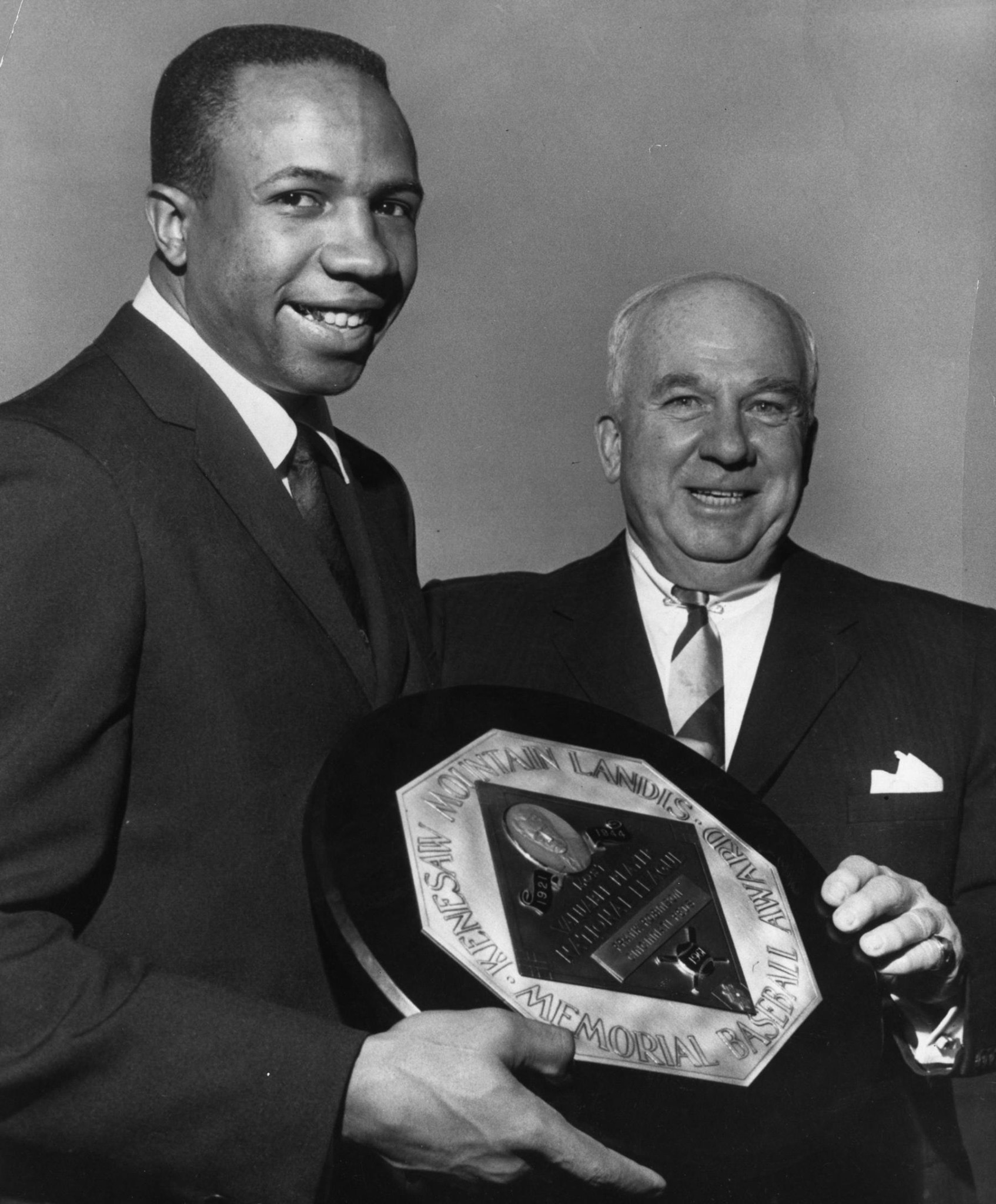

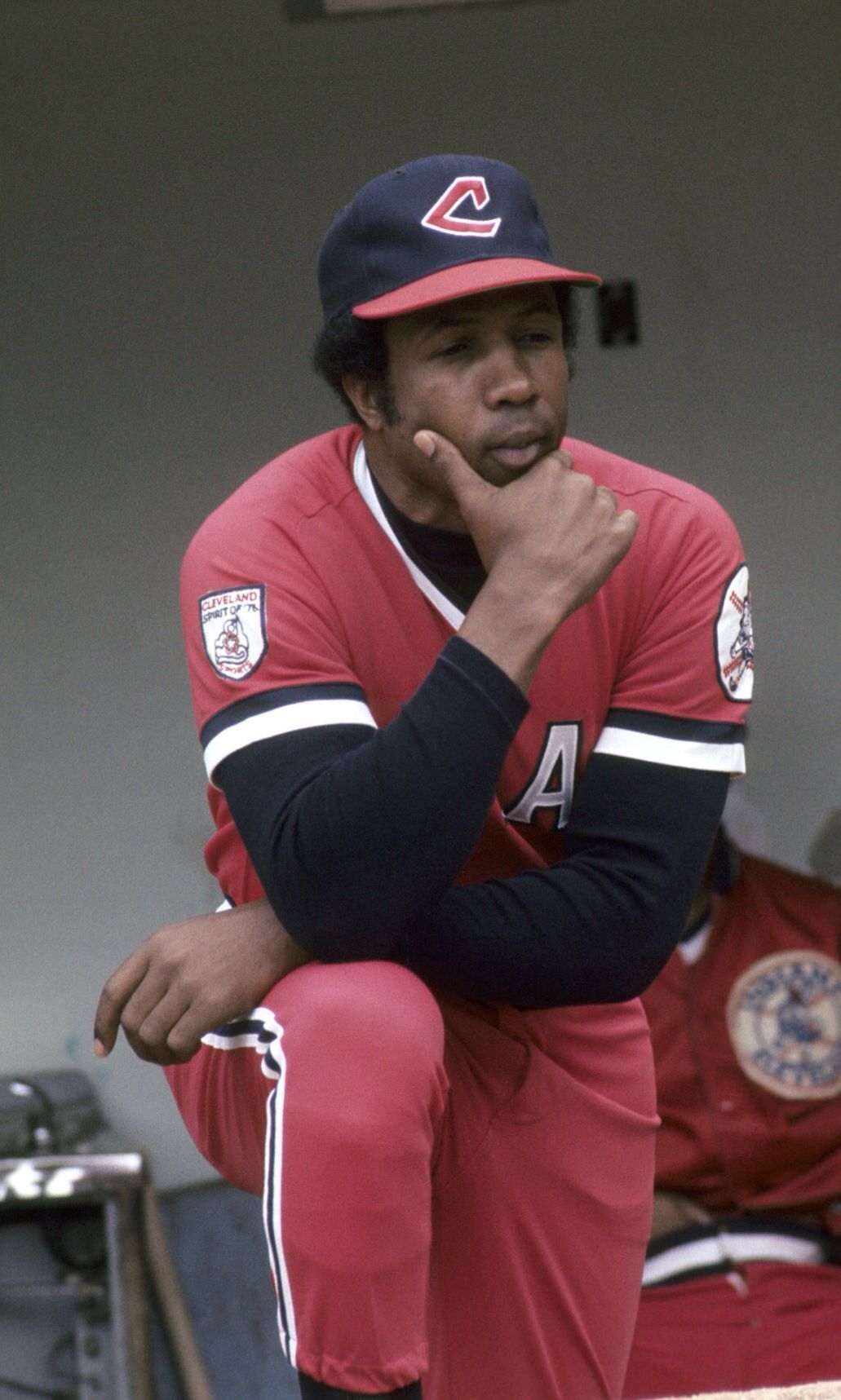

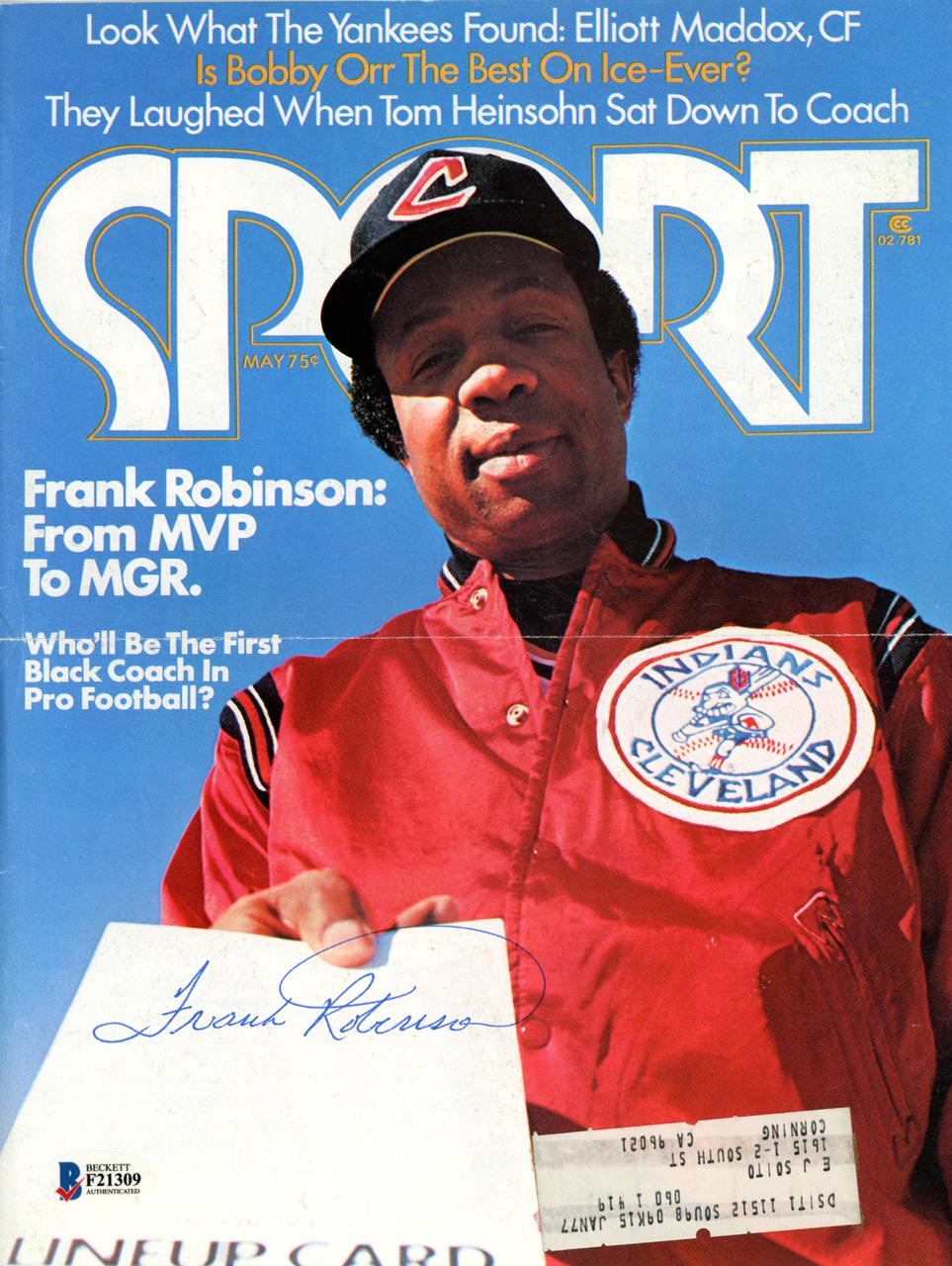

Robinson became Major League Baseball’s first black manager in 1975, when the Indians made him their player-manager prior to the start of the season. The 40-year-old Robinson gradually eased himself out of the lineup over the course of the season, one in which he led the Indians to their first winning record (81-78) since 1968. However, Robinson was relieved of his duties when the team started slowly in 1977. He spent the remainder of that year coaching for the Angels, before rejoining the Orioles organization the following year, first as a coach, and later as a minor league manager. Robinson returned to the major leagues as a manager with the San Francisco Giants from 1981 to 1985, before joining the Orioles once more as a coach in 1986. He replaced Cal Ripken Sr. as the team’s manager early in 1988, losing his first 15 games before finally leading the Orioles to victory. Robinson turned Baltimore around the following year, earning A.L. Manager of the Year honors by leading his team to an 87-75 record and a close second-place finish in the A.L. East. Robinson continued to manage the Orioles until 1991. He subsequently spent some years as Major League Baseball’s Director of Discipline, before being asked by the commissioner to temporarily take over the managerial reins of the struggling Montreal Expos franchise in 2002. Robinson continued to serve as the team’s manager until the conclusion of the 2006 campaign, after the franchise moved to Washington and renamed itself the Nationals. Although he no longer works for baseball in any official capacity, Robinson occasionally makes his presence felt by commenting negatively on the manner in which current players tend to fraternize with one another on the field, both before and during games. He also remains a staunch critic of those players who use any form of performance-enhancing drugs, expressing his regret that three of the four players who passed him on the all-time home run list since he retired are known steroid users.

In addition to hitting 586 home runs over the course of 21 major league seasons, Robinson compiled 1,812 runs batted in, 1,829 runs scored, 2,943 hits, and a .294 career batting average. He surpassed 30 home runs 11 times, 100 runs batted in six times, 100 runs scored eight times, 20 stolen bases three times, and batted over .300 on nine separate occasions. In addition to leading his league in home runs, runs batted in, and batting average once each, he topped his circuit in runs scored three times, on-base percentage twice, and slugging percentage four times. Robinson was selected to the All-Star team in 12 different seasons. Even in this age of free agency when players change teams and leagues so frequently, Robinson remains the only player in baseball history to win the Most Valuable Player Award in each league. He also finished in the top 10 in the balloting seven other times.

Yet, in spite of all his accomplishments, Frank Robinson remains one of the most underrated and overlooked truly great players in baseball history. Mike Schmidt grew up in the Cincinnati area as a Reds fan – and as a Frank Robinson fan in particular. The third baseman expressed his admiration for his fellow Hall of Famer by saying, “Of all the players who have ever played this game, Frank Robinson may well be the most underrated.”

Former Dodgers and Pirates shortstop Maury Wills echoed Schmidt’s sentiments when he stated, “Although he was often overlooked in favor of Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Roberto Clemente, Frank Robinson could do everything any one of them could do…and some things better.”

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Cincinnati Reds (1956-1965)

Baltimore Orioles (1966-1971)

Los Angeles Dodgers (1972)

California Angels (1973-1974)

Cleveland Indians (1974-1976)

Managed

Cleveland Indians (1975-1977)

San Francisco Giants (1981-1984)

Baltimore Orioles (1988-1991)

Montreal Expos (2002-2004)

Similar: Hank Aaron, Vladimir Guerrero

Linked: Vada Pinson, Pete Rose, Brooks Robinson, Don Baylor

Best Season, 1966

Robinson won the AL MVP, hitting .316 with 49 taters and 122 RBI to win the Triple Crown. He led the Orioles to their first World Championship.

Awards and Honors

1956 NL Rookie of the Year

1958 NL Gold Glove

1961 NL MVP

1966 AL MVP

1966 AL Triple Crown

1966 ML WS MVP

1971 ML AS MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1961 World Series

1966 World Series

1969 American League Championship Series

1969 World Series

1970 American League Championship Series

1970 World Series

1971 American League Championship Series

1971 World Series

Factoid

Frank Robinson is the only player to win a Most Valuable Player Award in both the American and National leagues.

Where He Played: Robinson played about 60% of his defensive outfield games in right field. He played 37% in left. He also appeared at DH (321 games) and first base (305).

Milestones

Hit his 500th home run on September 13, 1971, against the Detroit Tigers.

Hitting Streaks

19 games (1961)

19 games (1961)

Transactions

Signed as an amateur free agent by Cincinnati Reds (1953); Traded by Cincinnati Reds to Baltimore Orioles in exchange for Milt Pappas, Jack Baldschun and Dick Simpson (December 9, 1965); Traded by Baltimore Orioles with Pete Richert to Los Angeles Dodgers in exchange for Doyle Alexander, Bob O’Brien, Sergio Robles and Royle Stillman (December 2, 1971); Traded by Los Angeles Dodgers with Bill Singer, Mike Strahler, Billy Grabarkewitz and Bobby Valentine to California Angels in exchange for Andy Messersmith and Ken McMullen (November 28, 1972); Traded by California Angels to Cleveland Indians in exchange for Ken Suarez, Rusty Torres and cash (September 12, 1974).

Most Walk-Off Home Runs, Career

Jimmie Foxx……..12

Mickey Mantle……12

Stan Musial……..12

Frank Robinson…..12

Babe Ruth……….12

Tony Perez………11

Dick Allen………10

Harold Baines……10

Reggie Jackson…..10

Mike Schmidt…….10

Home Run Facts

Robinson’s 493rd homer, which tied him with Lou Gehrig on the all-time list, was the only hit allowed by Dick Drago in a rain-shortened game between the Orioles and Royals on July 30, 1971. Robinson’s O’s won the game, 1-0.

All-Star Selections

1956 NL

1957 NL

1959 NL

1961 NL

1962 NL

1965 NL

1966 AL

1967 AL

1969 AL

1970 AL

1971 AL

1974 AL

Replaced

Robinson took over in left field for the Reds in 1956, replacing a group of outfielders who had roamed out there in ’55. That group included Stan Palys, Bob Thurman, Chuck Harmon and Ray Jablonski.

Replaced By

Robinson’s last full-time job was as the Angels DH in 1974. The next season, with Robby off to Cleveland, the Halos turned to Tommy Harper, Joe Lahoud and some others to fill the DH role.

Best Strength as a Player

Speed and power

Largest Weakness as a Player

None

Other Resources & Links