Reggie Jackson Baseball Biography

Reggie Jackson

Position: Rightfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Left

6-0, 195lb (183cm, 88kg)

Born: May 18, 1946 in Abington, PA

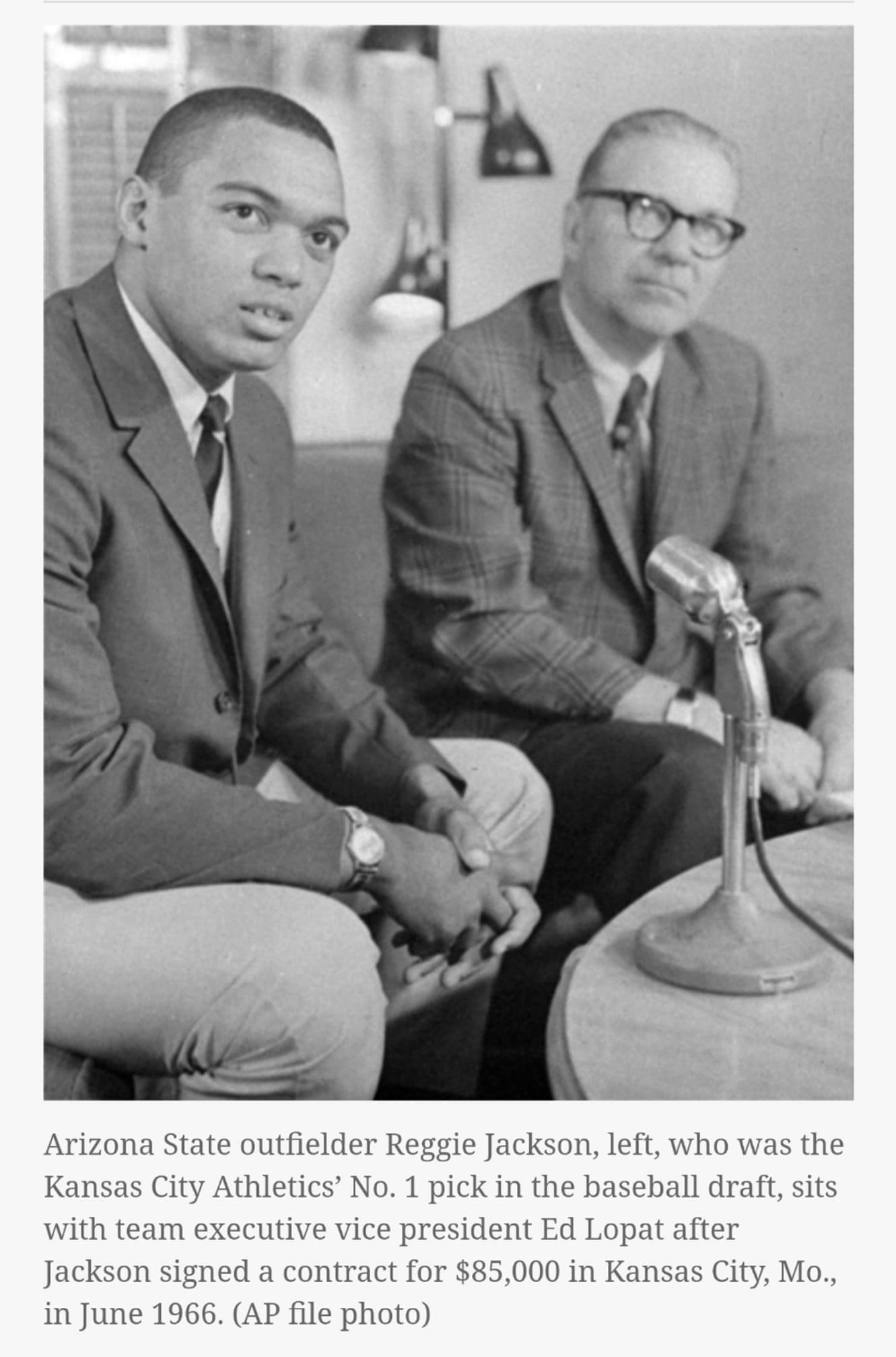

Draft: Drafted by the Kansas City Athletics in the 1st round (2nd) of the 1966 MLB June Amateur Draft from Arizona State University (Tempe, AZ).

High School: Cheltenham HS (Cheltenham, PA)

School: Arizona State University (Tempe, AZ)

Debut: June 9, 1967 (10,199th in MLB history)

vs. CLE 3 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: October 4, 1987

vs. CHW 3 AB, 2 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

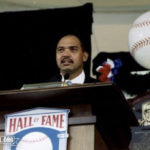

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1993. (Voted by BBWAA on 396/423 ballots)

View Reggie Jackson’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Reginald Martinez Jackson

Nicknames: Mr. October

Twitter: @mroctober

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Relatives: Cousin of Barry Bonds

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1967

Reggie Jackson

Graig Nettles

Rod Carew

Johnny Bench

Tom Seaver

Jerry Koosman

Amos Otis

Sparky Lyle

Aurelio Rodriguez

The Reggie Jackson Teammate Team

C: Thurman Munson

1B: Rod Carew

2B: Bobby Grich

3B: Graig Nettles

SS: Bert Campaneris

LF: Joe Rudi

CF: Fred Lynn

RF: Jose Canseco

DH: Mark McGwire

SP: Catfish Hunter

SP: Vida Blue

SP: Jim Palmer

SP: Ron Guidry

SP: Don Sutton

RP: Goose Gossage

M: Billy Martin

Notable Events and Chronology for Reggie Jackson Career

Known as much for his colorful and controversial persona as for his mammoth home runs, Reggie Jackson was one of the most exciting and charismatic players of his era. A master at self-promotion, Jackson backed up his words by hitting 563 home runs over the course of 21 major-league seasons, while also driving in 1,702 runs and scoring 1,551 others. The fact that Jackson batted just .262 and struck out an all-time record 2,597 times during his career didn’t seem to matter much since the enigmatic slugger always rose to the occasion when the stakes were highest. Jackson hit 18 home runs, knocked in 48 runs, and batted .278 in 281 career postseason at-bats. Particularly outstanding in World Series play, Jackson totaled 10 homers, 24 runs batted in, 21 runs scored, and batted .357 in 98 official plate appearances in the Fall Classic, leading his teams to five world championships.

Biography

Born in Wyncote, Pennsylvania on May 18, 1946, Reginald Martinez Jackson, as his name suggests, came from a multi-racial background. The son of a Puerto Rican mother and an African-American father, Jackson shared his childhood with six older siblings, two of whom came from his father’s first marriage. Jackson became the product of a broken home at an early age when his mother and father divorced. His mother subsequently left the Jackson household, taking three of her children with her. Young Reginald stayed behind with his father, half-brother, and sister.

Being raised solely by his father caused Reggie to view his dad very much in a heroic light. A former Negro League second baseman with the Newark Eagles, Martinez Jackson ran a dry-cleaning and tailoring shop that occupied the first floor of the family home. The elder Jackson instilled in his son a sense of self-discipline and a strong desire to succeed. Reggie later recalled, “To this day, my father is almost a mythical figure to me….’You’ve always got to show initiative, Reggie,’ he’d tell me. ‘You’ve got to have ambition, or you won’t amount to a hill of beans.'” Jackson’s demanding father required excellence in everything, from clothes to speech. The younger Jackson wrote in his autobiography, “Clean was the thing: Dad always demanded clean. . . . Biggest sin in the world was to get the school clothes dirty. If I did, there was no discussion, nothing to argue about. If there were any problems with the clothes, there was always an excellent chance that Martinez Jackson would be looking to give a lickin.'”

The younger Jackson likely acquired his athleticism from his father. While growing up in Wyncote, the former developed outstanding skills in football, basketball, baseball, and track and field, before starring in all four sports at Cheltenham High School. The rather tolerant racial attitude of Wyncote’s predominantly Jewish population also enabled Jackson to develop an active social life, even though his family remained one of the few black households in town.

After enjoying all the perks of being a star athlete in his hometown, Jackson experienced his first setback in his junior year of high school when the tailback tore up his knee in an early season football game. Told by doctors his playing career was over, Jackson nevertheless returned for the season’s final game. However, he fractured five cervical vertebrae during the contest, causing him to spend six weeks in the hospital, and another month in a neck cast. Jackson healed in time for the start of the baseball season, though, starring both at the bat and on the mound for his high school team. He then received yet another setback during his senior year when his father was sentenced to six months in jail for bootlegging.

College Career

After graduating from high school, Jackson soon began fielding scholarship offers from numerous colleges wishing to acquire him for their football programs. He also received offers from several major league baseball teams. Since Jackson’s father wanted him to be the first in the family to attend college, he eventually elected to attend Arizona State University on a football scholarship, knowing that the university also had one of the nation’s finest baseball programs.

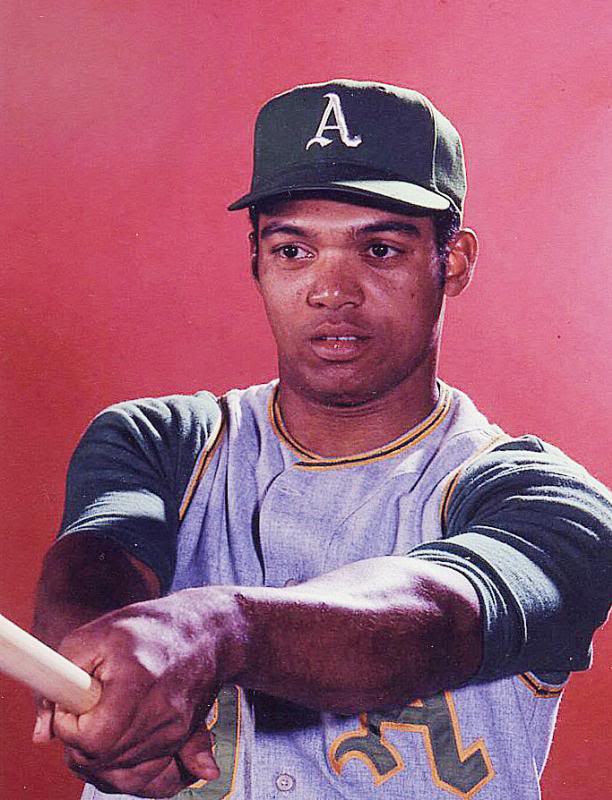

Jackson seemed to have a promising career ahead of him in football after ASU head coach Frank Kush selected him to join his squad. However, the freshman balked at the idea of becoming a defensive back, causing him to concentrate solely on baseball the following year. Honing his skills under head baseball coach Bobby Winkles, Jackson developed into one of the nation’s top prospects, earning first team All-American honors as a sophomore. After being selected by the Kansas City Athletics with the second overall pick of the 1966 Major League Baseball Draft, the 20-year-old outfielder began his professional career with the Single-A Lewis-Clark Broncs.

Kansas City/Oakland Years

Jackson progressed rapidly through Kansas City’s farm system, spending less than two full seasons in the minor leagues. However, he got his first taste of racism while playing for the team’s Double-A affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama. Jackson later credited the squad’s manager, John McNamara, with helping him through that difficult period in his life.

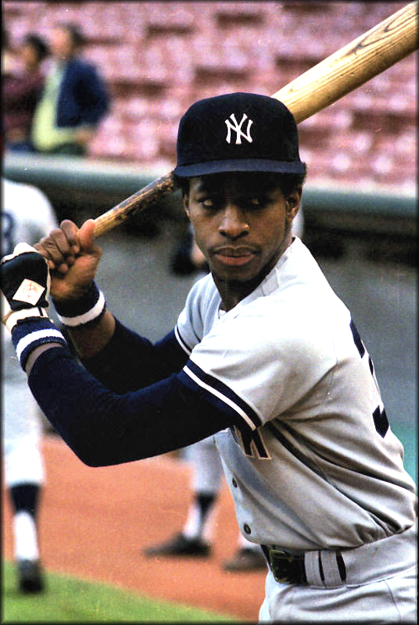

Called up by Kansas City in June of 1967, Jackson struggled terribly at the plate in his first trial in the majors. Appearing in 35 games, he hit just one home run, knocked in only six runs, batted just .178, and struck out 46 times in only 118 official at-bats. Yet, A’s management remained convinced the young outfielder had a bright future ahead of him. So, too, did Jackson, who possessed a tremendous amount of self-confidence that seemed to border on arrogance. Carrying himself with a swagger that suggested he believed fully in his own abilities, Jackson often rubbed other people the wrong way. Yet, the young outfielder’s teammates found it difficult to ignore his tremendous natural gifts. The 6’0″, 200-pound Jackson had exceptional physical strength, outstanding speed, and a strong throwing arm. While he lacked superior instincts and soft hands in the outfield, Jackson’s awesome power at the plate enabled his detractors to overlook his other flaws.

The A’s moved from Kansas City to Oakland in 1968, and playing on the West Coast seemed to agree with Jackson. Although he batted just .250 and struck out a league-leading 171 times, the 22-year-old outfielder hit 29 home runs, knocked in 74 runs, and scored 82 others. In an attempt to reduce Jackson’s strikeout total by cutting down somewhat on his swing, team owner Charlie Finley summoned San Francisco native Joe DiMaggio to work with the lefthanded-hitting slugger prior to the start of the 1969 campaign. Even though the talented youngster subsequently led the American League in strikeouts for the second straight season, with 142, he developed into a full-fledge star under DiMaggio’s tutelage. After compiling 40 home runs over the season’s first four months, Jackson finished the campaign with 47 homers. He also knocked in 118 runs, improved his batting average to .275, led the league with 123 runs scored and a .608 slugging percentage, and walked a career-high 114 times, enabling him to post an outstanding .410 on-base percentage.

An off-season contract dispute with Finley led to a poor 1970 campaign by Jackson. The outfielder’s home run total fell to just 23, and he knocked in only 66 runs, scored just 57 others, batted only .237, and struck out 135 times, leading the league in that category for the third of four consecutive times. Jackson rebounded the following season, though, improving his numbers to 32 homers, 80 runs batted in, 87 runs scored, and a .277 batting average. Jackson’s solid performance earned him a spot on the American League All-Star Team, enabling him to gain national attention by providing fans with one of the most memorable moments in the history of the Midsummer Classic.

Pinch-hitting early in the contest against Pittsburgh’s Dock Ellis, Jackson drove a fastball from the right-hander far above the right-field stands. Continuing to rise as it apparently headed out of the ballpark, the drive struck the transformer of a light standard on the right field roof. Closest estimates later indicated that the ball likely would have traveled well over 500 feet had its flight not been interrupted.

Jackson’s A’s captured the first of five straight A.L. West titles in 1971, but they came up short against Baltimore in the ALCS. However, a more mature A’s squad won the first of three consecutive world championships the following year, establishing themselves in the process as a baseball dynasty. Oakland boasted an excellent pitching staff that featured starters Jim “Catfish” Hunter, Vida Blue, and Ken Holtzman, along with bullpen ace Rollie Fingers. The A’s also had a solid lineup that included power-hitting third baseman Sal Bando, All-Star leftfielder Joe Rudi, and shortstop Bert Campaneris, who served as the team’s offensive catalyst. Jackson, though, remained the club’s most dynamic offensive performer, consistently leading the team in home runs, while striking fear into the hearts of opposing pitchers. Although he hit only 25 home runs and knocked in just 75 runs in 1972, Jackson was considered to be the primary threat in Oakland’s lineup. He performed well during the A’s five-game playoff victory over Detroit, scoring the tying run in the Series finale on a steal of home. However, he tore his hamstring on the play, leaving him unable to participate in the World Series.

Returning to Oakland’s lineup fully healthy in 1973, Jackson had arguably his finest all-around season. In leading the A’s to their second straight title, the right-fielder led the American League with 32 home runs, 117 runs batted in, 99 runs scored, and a .531 slugging percentage, while also stealing 22 bases and raising his batting average to .293. Jackson’s exceptional all-around performance earned him A.L. MVP and Major League Player of the Year honors. After struggling against Baltimore during the ALCS, Jackson then began to establish his legacy as Mr. October by batting .310, hitting one home run, and driving in six runs against the Mets in the World Series, en route to winning Series MVP honors. Jackson had another outstanding year in 1974, helping the A’s capture their third straight championship by placing among the league leaders with 29 home runs, 93 runs batted in, 90 runs scored, and a .514 slugging percentage, while also batting .289.

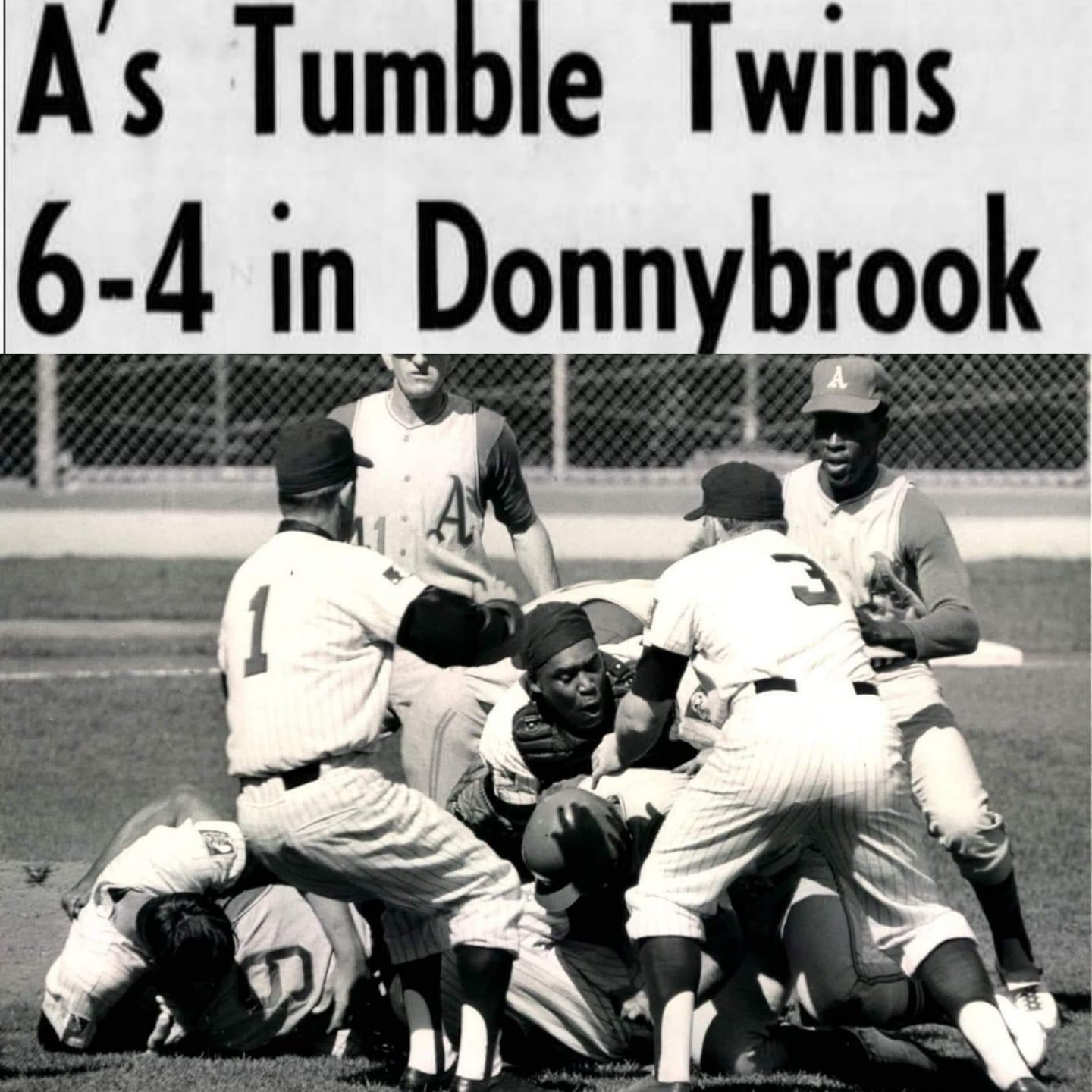

The Oakland clubs that ruled the baseball world from 1972 to 1974 were an unruly and rebellious bunch, often taking their cue from their unconventional owner Charlie Finley. Oakland’s owner not only shared an adversarial relationship with baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn, but he also constantly feuded with his own players. Finley’s rambunctious personality filtered down to the members of his team, who quarreled with one another off the field, while somehow managing to remain a cohesive unit on the diamond. As Oakland’s biggest star, Jackson came to symbolize the defiant nature of the squad. He squabbled with Finley in the local newspapers, engaged in a well-publicized clubhouse brawl with fellow Oakland outfielder Bill North in 1974, and occasionally displayed his dissatisfaction with team management by giving less than 100 percent between the white lines. Sports author Dick Crouser once wrote, “When the late Al Helfer was broadcasting the Oakland A’s games, he was not too enthusiastic about Reggie Jackson’s speed or his hustle. Once, with Jackson on third, teammate Rick Monday hit a long home run. ‘Jackson should score easily on that one,’ commented Helfer. Crouser also noted, “Nobody seems to be neutral on Reggie Jackson. You’re either a fan or a detractor.”

Jackson developed into such a polarizing figure largely because of his egocentric personality, which caused him to constantly crave the spotlight. When asked if Jackson was a hotdog (i.e. a show-off), Oakland teammate Darold Knowles responded, “There isn’t enough mustard in the world to cover Reggie Jackson.”

Nevertheless, Jackson continued to perform on the field, leading the A’s to their fifth straight A.L. West title in 1975 by driving in 104 runs, scoring 91 others, and leading the league with 36 homers. Oakland, though, failed to advance to the World Series when Boston swept them in the ALCS.

Free Agency and New York Years

The 1975 campaign turned out to be Jackson’s last in Oakland. With free agency looming for the outfielder at the conclusion of the 1976 season, A’s owner Charlie Finley dealt his most prominent player to the Baltimore Orioles. Jackson spent one year in Baltimore, finishing among the league leaders with 27 home runs and 91 runs batted in, and topping the circuit with a .502 slugging percentage.

The American League’s most charismatic player began courting potential suitors shortly after the 1976 campaign ended. Although Jackson received substantial offers from several other teams as well, he eventually chose to sign with the New York Yankees. Explaining his decision, Jackson stated he selected the Yankees because “George Steinbrenner simply out-hustled everyone else.” The Yankee owner’s persistence certainly made a favorable impression on the market’s most sought-after free agent. There also is little doubt, though, that the five-year deal worth almost $3 million he offered Jackson helped the slugger make up his mind.

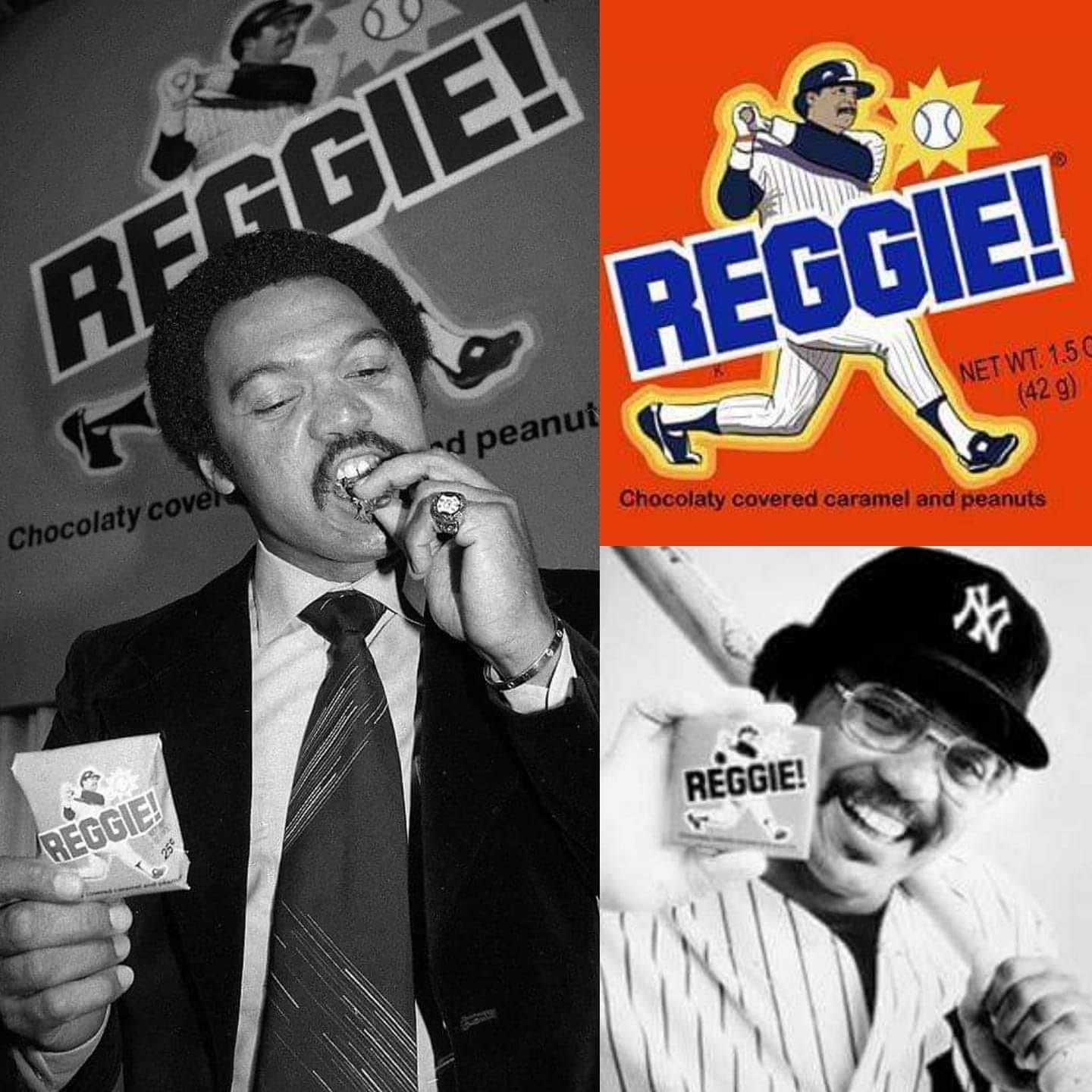

The marriage of Jackson and the Yankees seemed to be a natural: the American League’s most flamboyant player performing on the world’s largest stage. While still a member of the A’s in 1973, Jackson once boasted: “If I was playing in New York, they’d name a candy bar after me.” The outfielder again displayed his narcissistic tendencies when he announced shortly after signing with the Yankees, “I didn’t come to New York to be a star…I brought my star with me.”

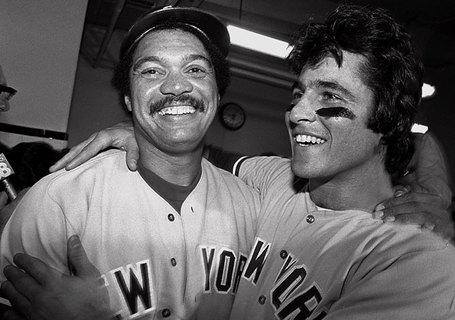

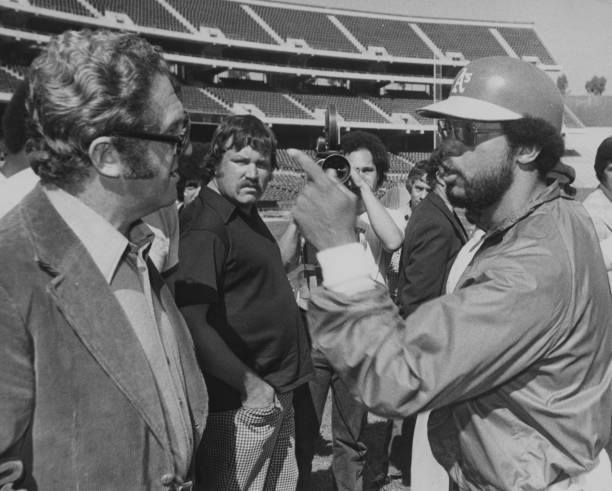

Jackson’s boastful manner alienated him from several of his new teammates before he even joined the club in spring training. Particularly resentful of the slugger was New York’s emotionally fragile manager Billy Martin, who viewed Jackson as a threat to his relationship with Steinbrenner. Nevertheless, Jackson’s reputation and immense talent forced even his harshest critics to acknowledge the importance of his acquisition. Jackson, though, created additional feelings of animosity when he made several ill-advised comments during a supposedly off-the-record conversation with SPORT magazine writer Robert Ward during spring training.

As the two men sat together having drinks at a local bar, the subject of Jackson’s potential contributions to the team arose. According to Jackson, he noted that the Yankees had won the pennant the previous year, but subsequently lost the World Series to the Cincinnati Reds in four straight games. The team’s new right-fielder then suggested that New York needed one more thing to win it all, and pointed out the various ingredients in his drink. Ward suggested that Jackson might be “the straw that stirs the drink,” a notion with which the slugger found no fault. However, when the story appeared in the May 1977 issue of SPORT, Ward quoted Jackson as saying, “This team, it all flows from me. I’m the straw that stirs the drink. Maybe I should say me and (Thurman) Munson, but he can only stir it bad.”

Although Jackson has continued to suggest that his comments were taken out of context, and that he never said anything negative about Munson during the interview, Ward has maintained through the years that he quoted Jackson accurately. Giving further credence to Ward’s version of the story is an article that later appeared in the New York Times in which writer Dave Anderson revealed that the slugger made similar comments to him during a July 1977 conversation. Anderson suggested that Jackson told him, “I’m still the straw that stirs the drink. Not Munson, not nobody else on this club.”

Munson’s status as team captain and arguably the most beloved player on the Yankees caused virtually all his teammates to develop a distaste for Jackson. Several of them never forgave the slugger, while others eventually learned to accept his boastful manner as a necessary evil. Jackson later attempted to explain his actions by saying, “I wanted to be part of the Yankee family, and when everyone didn’t greet me with open arms, I drew back, got more insecure, and started running my mouth a little.”

Jackson’s braggadocio made his first several months in New York extremely difficult ones, especially since it further intensified manager Billy Martin’s feelings of resentment towards him. Martin refused to bat Jackson in the prestigious cleanup spot in the batting order, choosing instead to place him in either the fifth or sixth slot. The relationship between the two men grew increasingly contentious over the course of the season, until their anger finally boiled over on June 18 during a 10-4 loss to the Boston Red Sox in a nationally-televised game at Fenway Park. Feeling that Jackson failed to properly charge a bloop hit by Red Sox slugger Jim Rice, Martin immediately replaced his right-fielder with Paul Blair. When Jackson arrived at the Yankee dugout, Martin confronted him at the top step, yelling that Jackson had shown him up. As the two men continued to argue, Jackson claimed that Martin’s heavy drinking had impaired his judgment. Despite being 18 years older, two inches shorter, and some 40 pounds lighter than Jackson, the irate Yankee manager lunged at the superstar outfielder, prompting coaches Yogi Berra and Elston Howard to quickly restrain him.

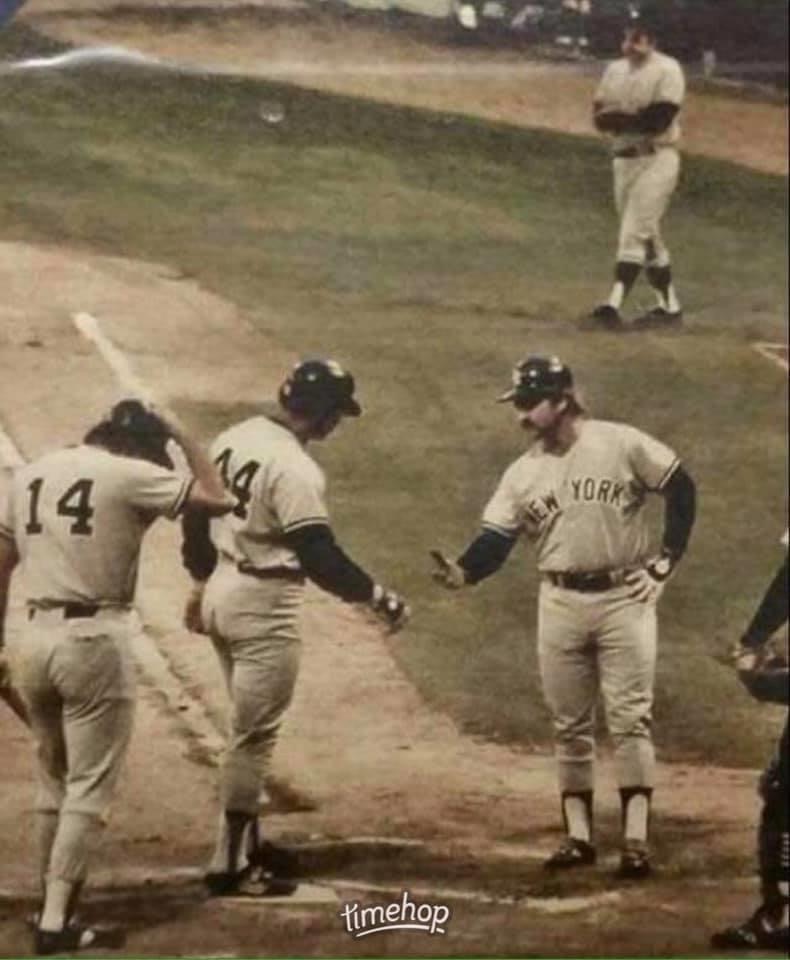

Even though Jackson experienced a tremendous amount of adversity during his first year in pinstripes, he ended up having a very productive season. The 31-year-old outfielder batted .286, scored 93 runs, stole 17 bases, and led New York with 32 home runs and 110 runs batted in. Particularly effective after team leaders Munson and Lou Piniella convinced Martin to bat Jackson cleanup, he hit 13 home runs and knocked in 49 runs over his final 50 games. Jackson’s strong second-half performance helped the Yankees win the A.L. East by a margin of 2 ½ games over Boston and Baltimore. They then faced Kansas City in the ALCS for the second straight year, once again coming out on top in a hard-fought five-game series. Although Jackson struggled terribly at the plate against the Royals, he delivered a huge hit during New York’s late inning, come-from-behind rally in the decisive fifth game. His greatest heroics, though, had yet to come.

The Yankees took a 3-2 lead against the Dodgers in the World Series, which returned to Yankee Stadium for Game Six. Jackson, who hit a home run in each of the previous two contests, drew a four-pitch walk in his first plate appearance. In a truly amazing performance, he then proceeded to hit three consecutive home runs, each on the first pitch, against three different Dodger pitchers. The last blast, a towering drive into the black-painted batter’s eye seats well beyond the centerfield wall, some 475 feet from home plate, enabled Jackson to join Babe Ruth as the only players ever to hit three home runs in one World Series game. Since Jackson also homered off Don Sutton in his final at-bat in Game Five, he accomplished the remarkable feat of hitting four home runs on four consecutive swings of the bat against four different Dodger pitchers. Leading New York to victory almost singlehandedly in Game Six, Jackson earned Series MVP honors, becoming the first player to do so with two different teams. Mr. October finished the Fall Classic with five home runs, eight runs batted in, 10 runs scored, a .450 batting average, a .542 on-base percentage, and a .755 slugging percentage.

The toast of New York following his incredible 1977 World Series performance, Jackson nevertheless continued to experience problems with Billy Martin the following year, until the manager finally resigned under a cloud of controversy midway through the campaign. Buoyed by the confidence placed in him by new Yankee manager Bob Lemon, Jackson helped New York overcome a 14-game deficit to first-place Boston over the season’s final two months, finishing the year with 27 home runs and 97 runs batted in. He then lived up to his Mr. October billing by batting .462 against the Royals in the ALCS, before hitting two home runs, driving in eight runs, and batting .391 during New York’s six-game World Series triumph over Los Angeles.

Late Career and Legacy

Jackson spent three more years in New York, having his best season in 1980, when he led the American League with 41 home runs, knocked in 111 runs, scored 94 others, and batted a career-high .300, to earn a second-place finish to George Brett in the league MVP voting. A sub-par 1981 campaign by Jackson prompted George Steinbrenner to allow the right-fielder to leave via free agency at season’s end. The 36-year-old outfielder ended up signing with the California Angels, for whom he had his last big year. Jackson finished the 1982 season with 101 runs batted in, 92 runs scored, a .275 batting average, and a league-leading 39 home runs, prompting Steinbrenner to later admit that “…letting Reggie go was the biggest mistake I ever made.” Jackson spent four more years with the Angels, never again approaching those numbers, before ending his career back in Oakland in 1987.

A true winner and one of the greatest clutch performers in history, Jackson played on six pennant-winners and five world championship teams during his career. He also appeared in 14 All-Star Games and placed in the top 10 in the league MVP balloting a total of seven times. Jackson led the American League in home runs four times, runs batted in once, runs scored twice, and slugging percentage three times.

After his retirement as an active player, Jackson served briefly as a color commentator for television’s coverage of the American League Championship Series, before pursuing numerous business ventures that included an automobile dealership, serving as a product spokesman, and also serving as a real estate developer. He also served as an advisor to the Oakland A’s from 1988 to 1993, before assuming a similar role with the Yankees beginning in 1993.

Jim “Catfish” Hunter, a teammate of Jackson’s in Oakland and New York, once said of the controversial outfielder, “The thing about Reggie is that you know he’s going to produce. And if he doesn’t, he’s going to talk enough to make people think he’s going to produce.”

Hunter also stated on another occasion, “He’d give you the shirt off his back. Of course he’d call a press conference to announce it.”

Still, Reggie Jackson showed surprising humility during his Hall of Fame induction speech in 1993. After being elected to Cooperstown by the members of the BBWAA in his very first year of eligibility, Jackson stood before the assembled mass and proclaimed, “I know I wasn’t the best. All I have to do is look behind me….Thanks, Jackie (Robinson); thanks, Larry (Doby). We owe you.” He then ended his speech by saying, “Friends, in the words of Lou Gehrig, today, I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the earth. I’ve had a dream and I’ve been able to live it.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Kansas City Athletics (1967)

Oakland Athletics (1968-1975)

Baltimore Orioles (1976)

New York Yankees (1977-1981)

California Angels (1982-1986)

Oakland Athletics (1987)

Similar: None

Linked: Bob Welch, who struck him out in an epic confrontation in the 1978 World Series… Thurman Munson and Jackson competed for leadership on the 1970s Yankees. Munson never forgave Jackson for his “straw that stirs the drink” comment… Jose Canseco tried to learn everything he could from the elder Jackson when the two were teammates at the end of Reggie’s career, but failed to learn how to charm the press.

Best Season, 1969

He was just 23, but he had an awesome season, clubbing 47 homers. At the All-Star break it looked like he may challenge Maris’ record, but he slowed in the second-half as AL pitchers stayed away from him. He drove in 118, his career high. Jackson was still a five tool player, stealing 13 bases and using his rocket arm in right. He walked a career-best 114 times (he rarely came within 30 walks of that total).

Awards and Honors

1973 AL MVP

1973 ML WS MVP

1977 ML WS MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1971 American League Championship Series

1972 American League Championship Series

1973 American League Championship Series

1973 World Series

1974 American League Championship Series

1974 World Series

1975 American League Championship Series

1977 American League Championship Series

1977 World Series

1978 American League Championship Series

1978 World Series

1980 American League Championship Series

1981 American League Division Playoffs

1981 American League Championship Series

1981 World Series

1982 American League Championship Series

1986 American League Championship Series

Factoid

Three homers on three pitches and three swings in three straight-at-bats in Game Six of the 1977 World Series.

Where He Played: Reggie was a right fielder, when he didn’t DH. He played more than 2,000 games in the outfield, with about 90% of them in right. He was a DH in 630 games, or about four seasons worth of games.

Post-Season Notes

Reggie and Babe Ruth are the only two players to ever hit three home runs in a World Series game.

Transactions

Selected by Kansas City Athletics in the 1st round (2nd pick overall) of the free-agent draft (June 29, 1966); Traded by Oakland Athletics with Ken Holtzman and Bill VanBommell to Baltimore Orioles in exchange for Don Baylor, Mike Torrez and Paul Mitchell (April 2, 1976); Granted free agency (November 1, 1976); Signed by New York Yankees (November 29, 1976); Granted free agency (November 13, 1981); Signed by California Angels (January 22, 1982); Granted free agency (November 12, 1986); Signed by Oakland Athletics (December 24, 1986); Granted free agency (December 15, 1987).

Jackson played one season for Earl Weaver in Baltimore before jumping to the Yankees as a free agent. The O’s won five division titles during the decade of the 1970s, but failed when Reggie was there in 1976. Reggie missed about three weeks with injury but basically posted the sort of numbers he had in Oakland. He was Weaver’s sort of player (power and patience), but Jackson never took to the “Oriole Way.”

Factoid

Reggie Jackson led the American League in home runs with three different teams: the Oakland A’s, New York Yankees, and California Angels.

Quotes From Jackson

“As long as you have a bat in your hands you can rewrite the stories. You’ve got the last say. … It’s about the things you can control. As long as you have a bat in your hands, it doesn’t really matter.” — Jackson’s advice to Gary Sheffield, 2006

Factoid

While playing in New York, Reggie had a candy bar named after him, which prompted these comical responses: “The Reggie Bar is the only candy bar that unwraps itself and tells you how good it is,” and “It’s the only candy bar that tastes like a hot dog.”

All-Star Selections

1969 AL

1971 AL

1972 AL

1973 AL

1974 AL

1975 AL

1977 AL

1978 AL

1979 AL

1980 AL

1981 AL

1982 AL

1983 AL

1984 AL

Replaced

Mike Hershberger, the right fielder for the 1967 Kansas City A’s. Hershberger hung around with the A’s through 1969 as a fifth outfielder.

Replaced By

The A’s signed Don Baylor to be their DH in 1988, replacing Reggie in that role.

Best Strength as a Player

Ability to rise to the occasion.

Largest Weakness as a Player

Catching the ball.

Other Resources & Links