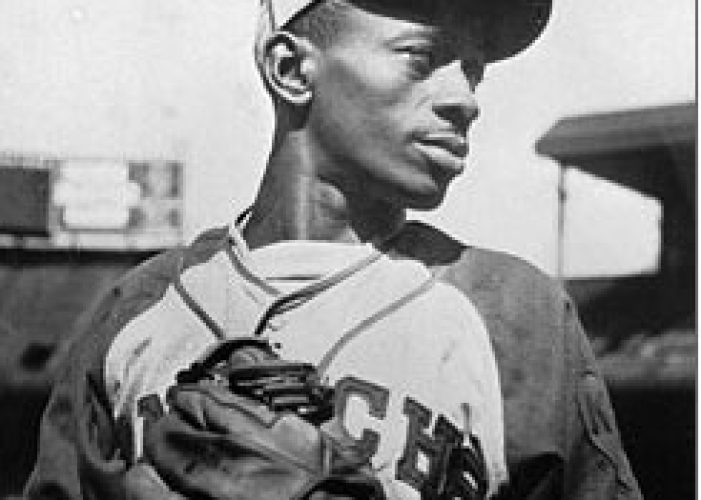

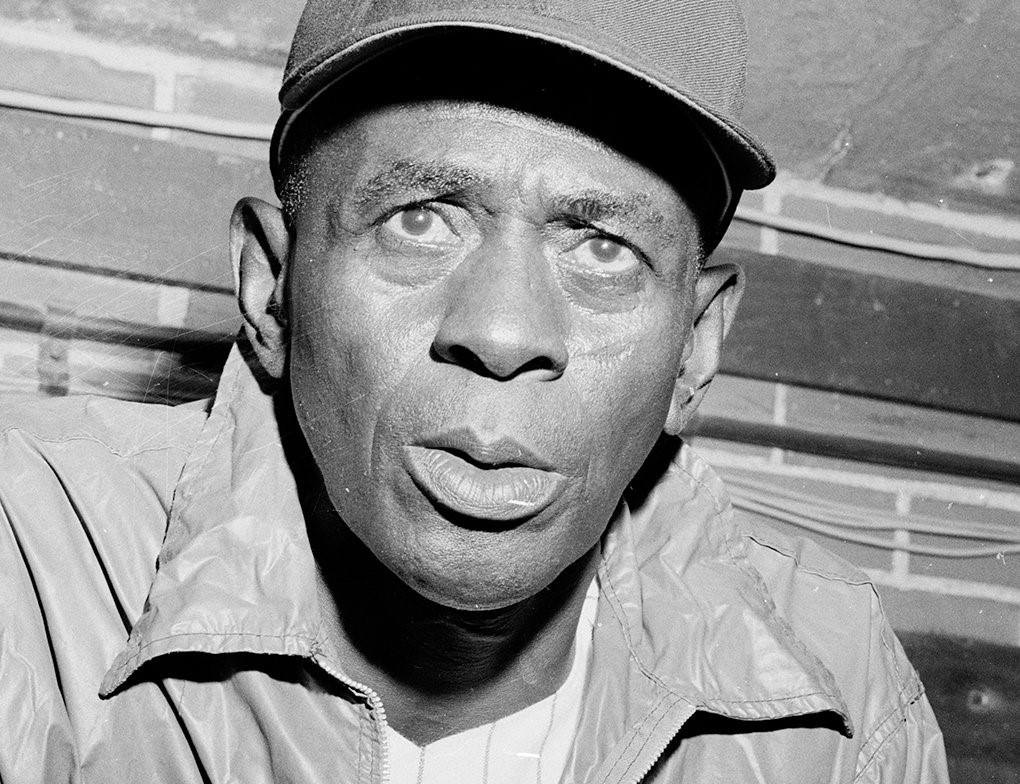

Satchel Paige

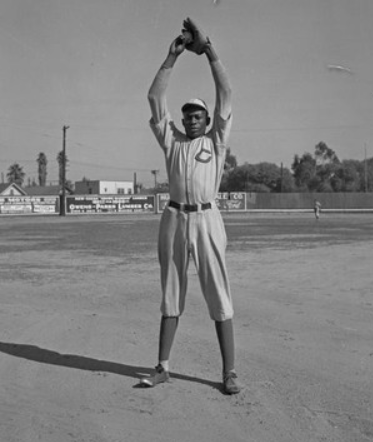

Position: Pitcher

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-3, 180lb (190cm, 81kg)

Born: July 7, 1906 in Mobile, AL

Died: June 8, 1982 in Kansas City, MO

Buried: Forest Hill Cemetery, Kansas City, MO

Debut: 1927 (6,458th in major league history)

AL/NL Debut: July 9, 1948

vs. SLB 2.0 IP, 2 H, 1 SO, 0 BB, 0 ER

Last Game: September 25, 1965

vs. BOS 3.0 IP, 1 H, 1 SO, 0 BB, 0 ER

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1971. (Voted by Negro League Committee)

View Satchel Paige’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Leroy Robert Paige

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1948

Roy Campanella

Richie Ashburn

Robin Roberts

Mike Garcia

Carl Erskine

Hank Bauer

Ray Boone

Don Mueller

Satchel Paige

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

In a Negro National League game, Satchel Paige pitches a 4 – 0 no-hitter for the Pittsburgh Crawfords against the Homestead Grays in Pittsburgh, with only a walk and an error spoiling a perfect game. He strikes out 17. Josh Gibson is his catcher, the only time in Negro league history in which battery-mates in a no-hitter are both members of the Hall of Fame, something which has never happened in the white majors. Legend claims that Paige then drives to Chicago to shut out the Chicago American Giants, 1 – 0, in 12 innings, giving him two shutouts in two different cities in the same day, but the claim has since been disproved. The no-hitter, however, is documented.

In Cleveland‚ 73‚484 fans watch the Indians and Yankees square off for 2 games. Trailing in the opener‚ an ailing Lou Boudreau hits a bases-loaded pinch single in the 7th to tie the game‚ and Satchel Paige wins it in relief‚ 8 – 6. Steve Gromek goes 7 innings in the nitecap to give the Indians a 2 – 1 win over rookie Bob Porterfield‚ making his major league debut.

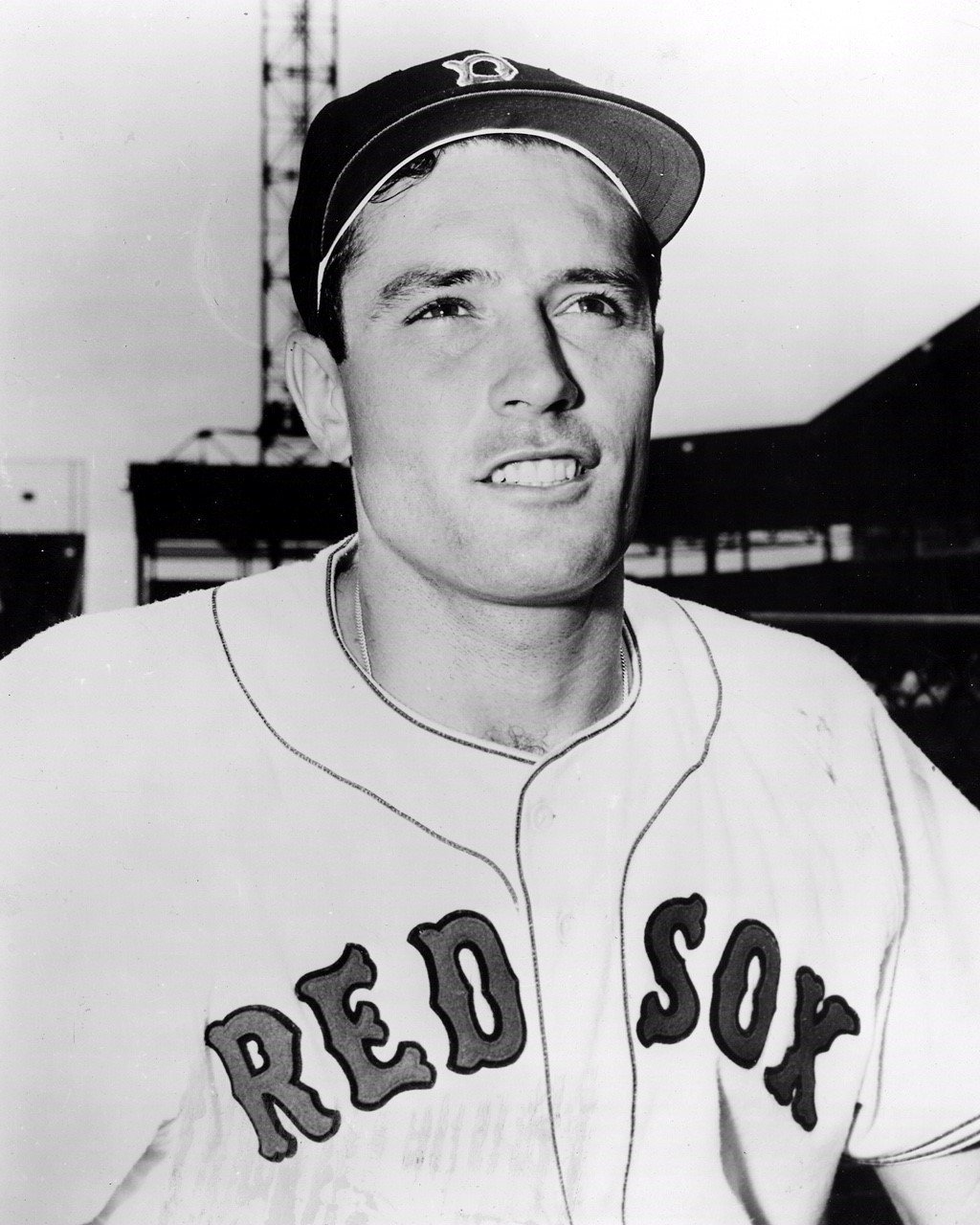

At Fenway Park‚ Bosox catcher Sammy White clouts a 9th-inning grand slam with one out to defeat the Browns’ Satchel Paige‚ 11 – 9. Paige (5-2) takes a 9 – 5 lead into the 9th. White completes his home run trot by rounding third base and crawling from half way home and kissing the plate. Another rookie provides entertainment to start the inning as Jimmy Piersall‚ leading off‚ announces to Paige that he is going to bunt. He does just that and beats Paige to first base‚ whereupon he starts mirroring Satchel’s moves and yelling “oink‚ oink‚ oink.” Hoot Evers beats out an infield hit and Piersall continues his antics at second. A now distracted and annoyed Paige walks George Kell‚ and one out later‚ forces in a run by walking Billy Goodman. A single by Ted Lepcio sets up White’s slam. After the game‚ Browns C Clint Courtney opines‚ “I believe that man is plumb crazy. Yeah‚ he’s nuts altogether. I never saw a man do those things. Anywhere.”

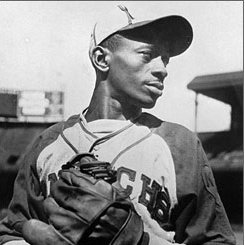

Biography

The most colorful and charismatic player in the history of black baseball, Leroy “Satchel” Paige reached legendary status during his 22-year playing career in the Negro Leagues. A prognosticator, an entertainer, a philosopher, and, most importantly, a phenomenal pitcher, Paige mesmerized and frustrated opposing batters for more than two decades with his wide assortment of pitches that included his Hesitation Pitch, Bat Dodger, Hurry-Up Ball, Midnight Rider, Jump Ball, and Midnight Creeper. Generally considered to be the greatest pitcher in Negro League history, Paige found himself unable to compete in the Major Leagues until 1948, when he was already 42 years of age. Nevertheless, he previously made enough of an impression on major league hitters during barnstorming tours to gain widespread recognition among them as one of the toughest pitchers they ever faced.

Although the exact date of his birth remained a mystery for many years, it eventually surfaced that Leroy Robert Paige was born on July 7, 1906 in a section of Mobile, Alabama known as Down the Bay. One of a dozen children born to John Page, a gardener, and Lula Page, a domestic worker, Leroy had the spelling of his last name changed to “Paige” by his mother during the mid-1920s, shortly before the start of his playing career. Paige later explained, “My folks started out by spelling their name ‘Page’ and later stuck in the ‘i’ to make themselves sound more high-tone.” The introduction of the new spelling coincided with the death of Paige’s father, perhaps suggesting the desire for a new start as well.

As was the case with his date of birth, various stories continued to surround the origin of Paige’s nickname through the years. However, a boyhood friend and neighbor of Paige’s once revealed that he gave his companion his nickname after Paige was caught trying to steal a bag. Young Leroy carried suitcases at a train station for tips, and, on one particular occasion, he attempted to steal a man’s satchel but was subsequently reprimanded by the owner, who ran him down and cuffed him about the head while recovering his property. In later years, Paige concocted various versions of the origin of his nickname that were more socially acceptable.

After displaying an earlier pattern of theft and truancy, Paige was committed to the state reform school following his arrest for shoplifting two weeks before his twelfth birthday. It was during his five years at the Industrial School for Negro Children in Mount Meigs, Alabama that Paige developed his pitching skills under the guidance of Edward Byrd. Paige developed his signature high leg-kick under Byrd’s tutelage, while also learning to swing his arm around during his delivery so it appeared as if his hand was in the batter’s face when he released the ball towards home plate. Having perfected his technique, Paige began playing semi-pro ball for several teams in Mobile after he was released from the reform school in December of 1923.

After spending two years in the semi-pro leagues, Paige received an offer in 1926 to join the Chattanooga White Sox of the minor Negro Southern League. Discovered by the team’s player/manager Alex Herman, a former friend from the Mobile slums, the 22-year-old Paige quickly accepted the offer, joining Chattanooga for the start of the 1926 campaign. The tall, lanky righthander took the league by storm, recording nine strikeouts

over six innings in one of his first starts, and subsequently gaining general recognition as the circuit’s best pitcher over the remainder of the season.

Paige’s contract was sold to the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro National League early in 1927. Although he struggled with his control at first, Paige gradually gained a better recognition of the strike zone and finished the year with a record of 7-1 and an ERA of 2.12 in official Negro League play. Paige continued to evolve as a pitcher with the Barons over the course of the next two seasons, while simultaneously adding to his arsenal of pitches. On April 29, 1929, he recorded 17 strikeouts in a game against the Cuban Stars. Paige then struck out 18 Nashville Elite Giants six days later, en route to compiling a league-leading total of 176 strikeouts for the year.

Paige’s success soon made him the league’s biggest drawing card, a fact that was not lost on Birmingham’s owner R.T. Jackson. The Barons owner began “renting” Paige out to other ball clubs for one or two games to help them improve their home attendance, with both Jackson and Paige receiving a portion of the profits. Paige spent much of the 1930 campaign being leased out to other teams by the Barons in this fashion. However, he began an even more nomadic existence in 1931, when Birmingham temporarily disbanded as a result of the Depression. Paige spent the next several seasons splitting his time between numerous teams, including the Cleveland Cubs, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Kansas City Monarchs, and Newark Eagles. He was at his very best with the Crawfords from 1932 to 1934, compiling records of 32-7 and 31-4 against all levels of competition in the first two seasons, before posting an official record of 14-2 in league games in 1934, while allowing only 2.16 runs per-game, recording 144 strikeouts, and surrendering just 26 walks.

Paige’s wiry 6’4″, 180-pound frame, unique delivery, wide assortment of pitches, and amazing talent all contributed to the incredible amount of success he experienced during his Negro League career. In discussing the technique he employed to baffle opposing hitters, Paige explained, “I use my single windup, my double windup, my triple windup, my hesitation windup, my no windup. I also use my step-n-pitch-it, my submariner, my sidearmer, and my bat-dodger. Man’s got to do what he’s got to do.”

Paige added, “I never threw an illegal pitch. The trouble is, once in awhile I toss one that ain’t never been seen by this generation.”

Paige’s legend was further enhanced by his colorful and flamboyant nature, which caused him to become the subject of often-repeated folklore. Stories surfaced about the times he instructed his outfielders to sit behind him in the infield while he proceeded to strike out the side with the tying run on base. Paige also enjoyed facing the opposing team’s best hitter when the game was on the line. On one occasion, he intentionally walked Howard Easterling and Buck Leonard to load the bases so he could pitch to Josh Gibson. Paige then struck out black baseball’s most dangerous hitter on three pitches. In another instance, Paige walked a batter, called over to him as he stood on first base, “There you is, and there you is going to stay,” then proceeded to strike out the next three batters.

Several Negro League players claimed that Paige was virtually impossible to hit. Hall of Famer Buck Leonard stated, “Satchel Paige was the toughest pitcher I ever faced. I couldn’t do much with him. All the years I played there, I never got a hit off of him. He threw fire.”

Major League hitters who faced Paige in exhibition games played during barnstorming tours expressed similar sentiments. Both Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio identified

Paige as the greatest pitcher they ever faced. Chicago Cubs Hall of Fame outfielder Hack Wilson said of the righthander’s fastball: “It starts out like a baseball, and when it gets to the plate, it looks like a marble.”

Perhaps Paige’s greatest admirer among major league players, though, was St. Louis Cardinals Hall of Fame pitcher Dizzy Dean, who the Negro League hurler often bested in head-to-head matchups in exhibition games. The equally outspoken Dean once boasted, “If Satch and I were pitching on the same team, we would clinch the pennant by July 4th and go fishing until World Series time.”

On one particular occasion, Paige and Dean hooked up in a 13-inning affair that Paige’s team finally won 1-0. At one point during the contest, Paige told his adversary, “I don’t know what you’re going to do Mr. Dean, but I’m not going to give up any runs if we have to stay here all night.”

Such efforts prompted Dean to later proclaim, “He’s a better pitcher than I ever hope to be.” The Cardinals righthander added, “My fastball looks like a change of pace alongside that little pistol bullet Satchel shoots up to the plate.”

After dominating Negro League batters for more than 20 years, Paige was understandably upset when Branch Rickey signed Jackie Robinson to a minor league contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1946. Although Paige later admitted in his autobiography that he would have considered a minor league assignment demeaning, he also wrote, “Signing Jackie like they did still hurt me deep down. I’d been the guy who’d started all that big talk about letting us in the big time. I’d been the one who’d opened up the major league parks to colored teams. I’d been the one who the white boys wanted to go barnstorming against.”

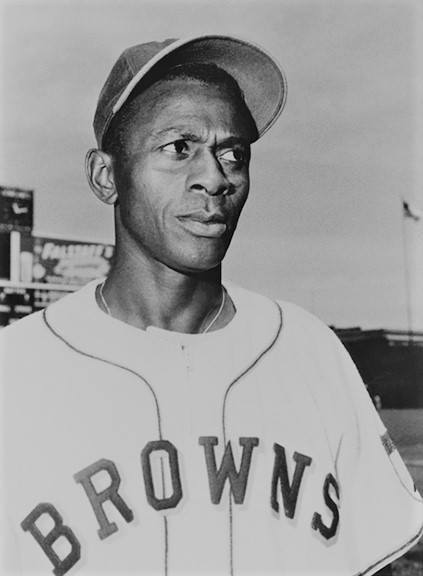

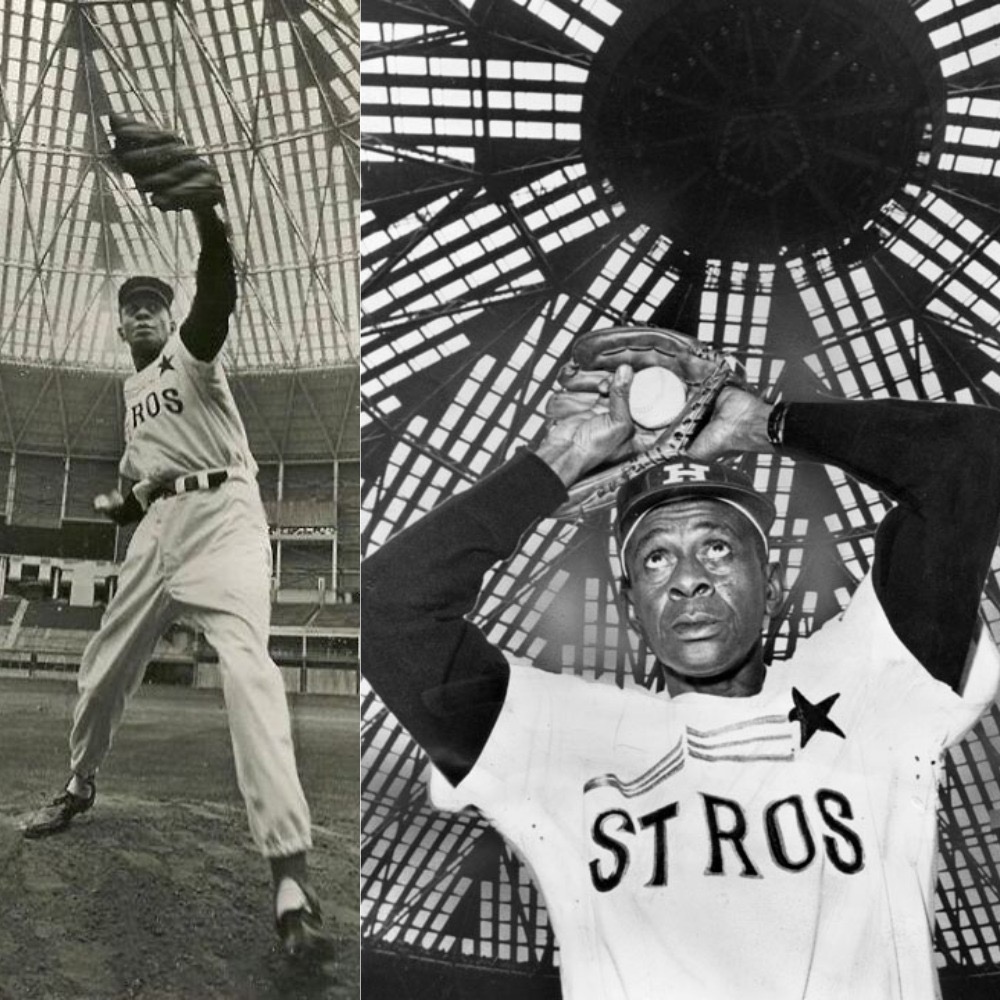

Paige finally got his chance to play in the major leagues in 1948, when Cleveland Indians owner Bill Veeck signed him to a contract to play for his team on Paige’s 42nd birthday. He made his major league debut in relief two days later, spending the final three months of the season splitting his time between the bullpen and the starting rotation. Paige finished the year with a record of 6-1 and a 2.48 ERA, helping the Indians win the American League pennant and capture their second world championship. Paige spent parts of five more seasons in the big leagues, compiling a career record of 28-31 and an ERA of 3.29, and being selected to appear in two All-Star Games.

In 1971, Paige became the first former Negro League star to be elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame. In the years after his induction, he continued to follow his own advice,”Don’t look back, something might be gaining on you.” Paige enjoyed the remaining years of his life until he died of a heart attack at his home in Kansas City during a power failure on June 8, 1982, one month before his 76th birthday.

Paige once said, “Ain’t no man can avoid being born average, but there ain’t no man got to be common.” There was nothing common about Satchel Paige.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon

Other Resources & Links

Baseball-Almanac.com Retrosheet Seamheads WhatIfSports: Satchel Paige