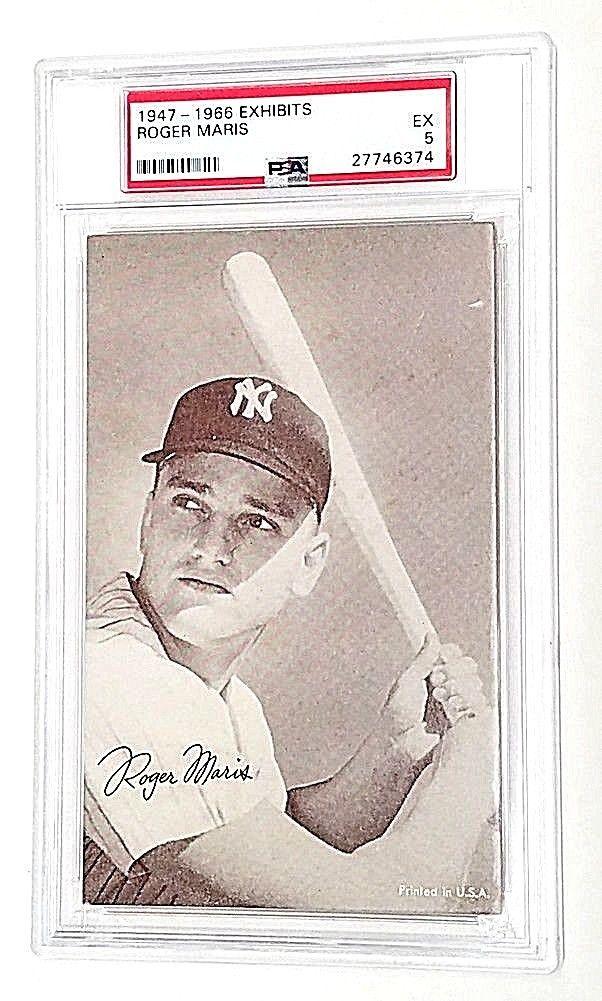

Roger Maris Stats & Facts

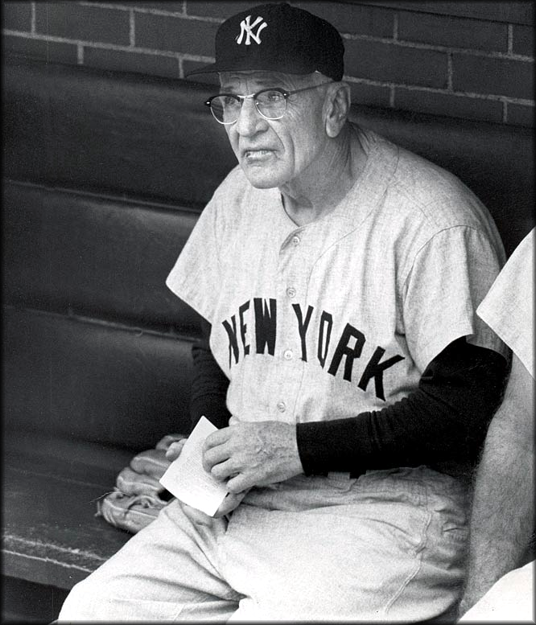

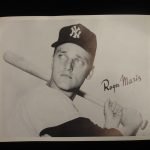

Roger Maris

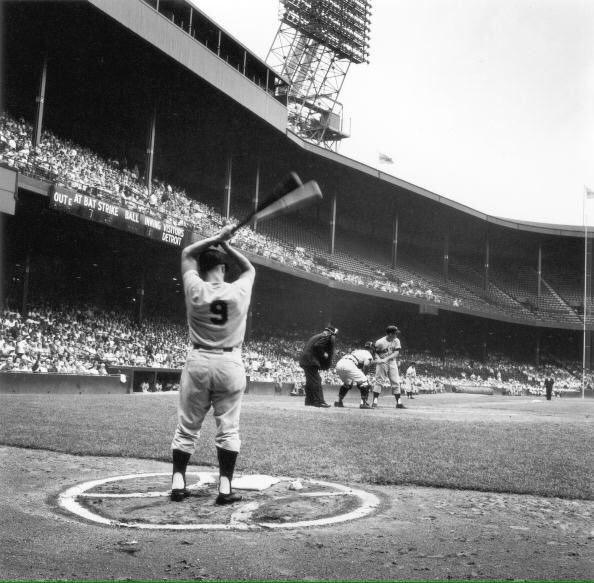

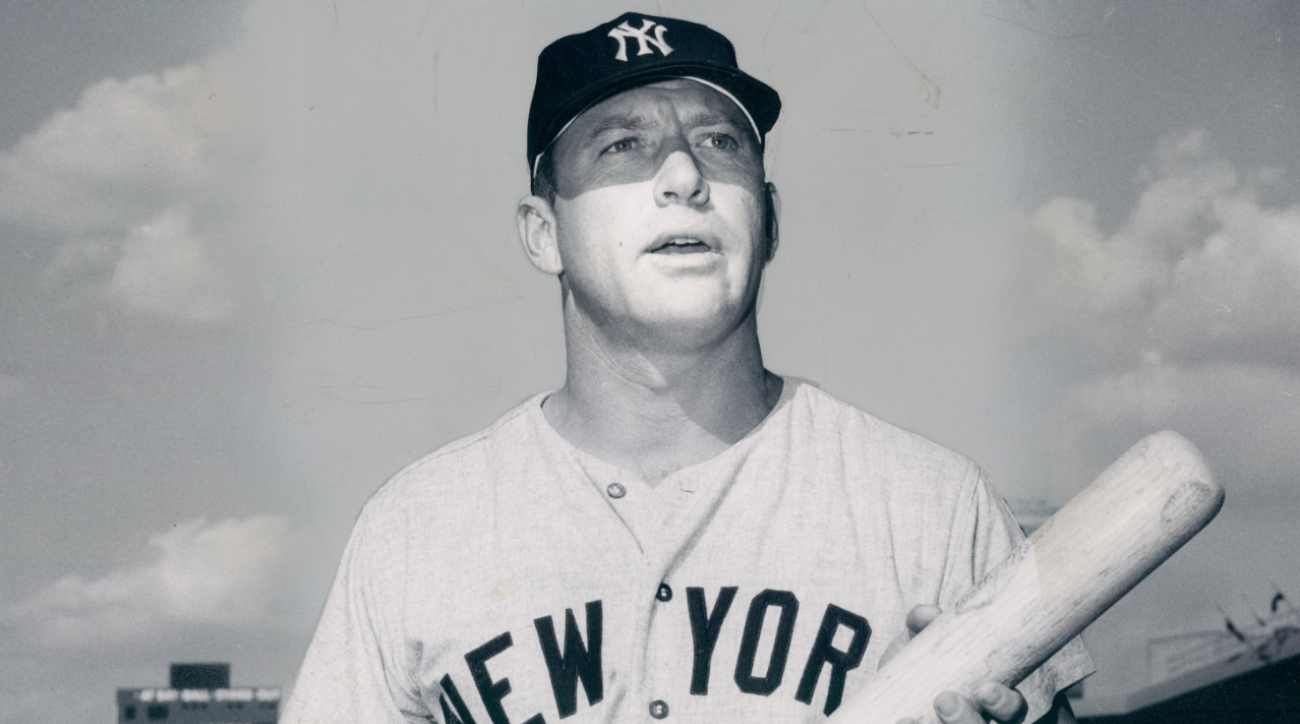

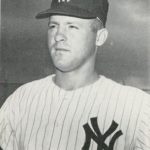

Position: Rightfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Right

6-0, 197lb (183cm, 89kg)

Born: September 10, 1934 in Hibbing, MN

Died: December 14, 1985 in Houston, TX

Buried: Holy Cross Cemetery, Fargo, ND

High School: Bishop Shanley HS (Fargo, ND)

Debut: April 16, 1957 (9,024th in MLB history)

vs. CHW 5 AB, 3 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 29, 1968

vs. HOU 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Full Name: Roger Eugene Maris

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Players Who Debuted Same Year

Coming Soon

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology for Roger Maris Career

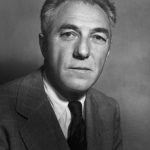

Biography

Perhaps the most misunderstood and misrepresented athlete of his time, Roger Maris was portrayed by the media as being sullen, moody, and arrogant. However, those who knew him well viewed Maris as someone who was quiet, shy, painfully honest, and totally unpretentious. Maris was also one of the finest all-around players of his generation, although he is remembered mostly as the man who broke Babe Ruth’s single-season home-run record.

Born to Croatian immigrants in Hibbing, Minnesota on September 10, 1934, Roger Eugene Maras spent most of his youth in Grand Forks and Fargo, North Dakota, where he attended Bishop Shanley High School. A gifted athlete, he changed his last name to Maris while starring in both baseball and football in high school. He still holds the official high school record for most kickoff return touchdowns in a game, with four.

Maris first exhibited his independent, no-nonsense type of personality after being recruited to play football at the University of Oklahoma. After arriving by bus in Norman and finding no one from the university there to greet him, he simply turned around and boarded the first bus back to Fargo.

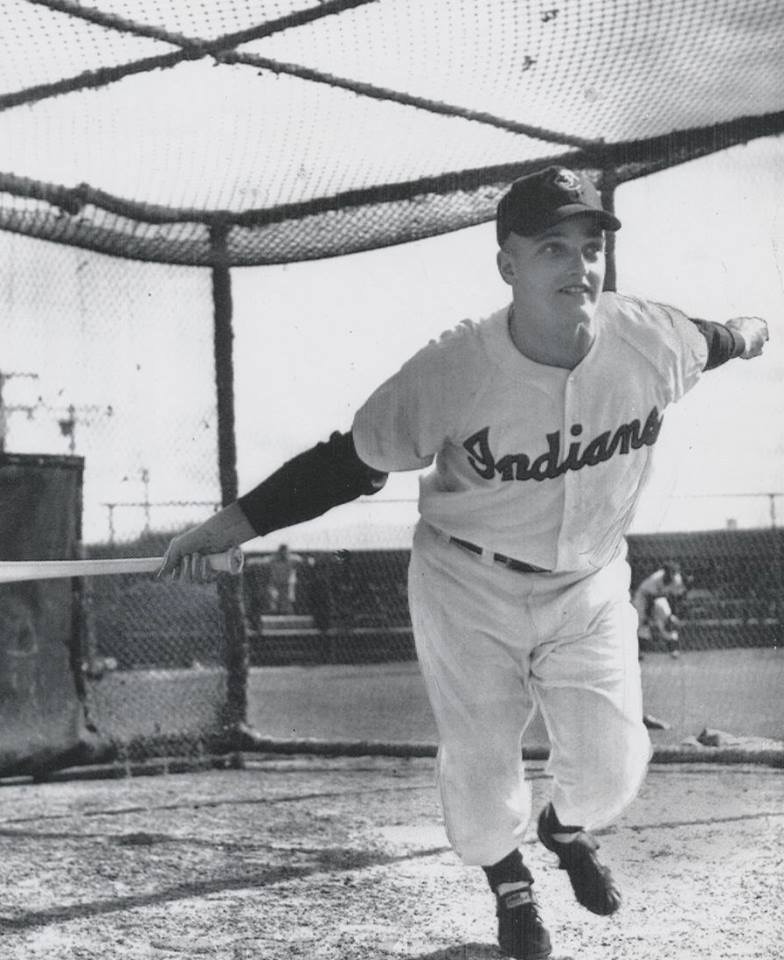

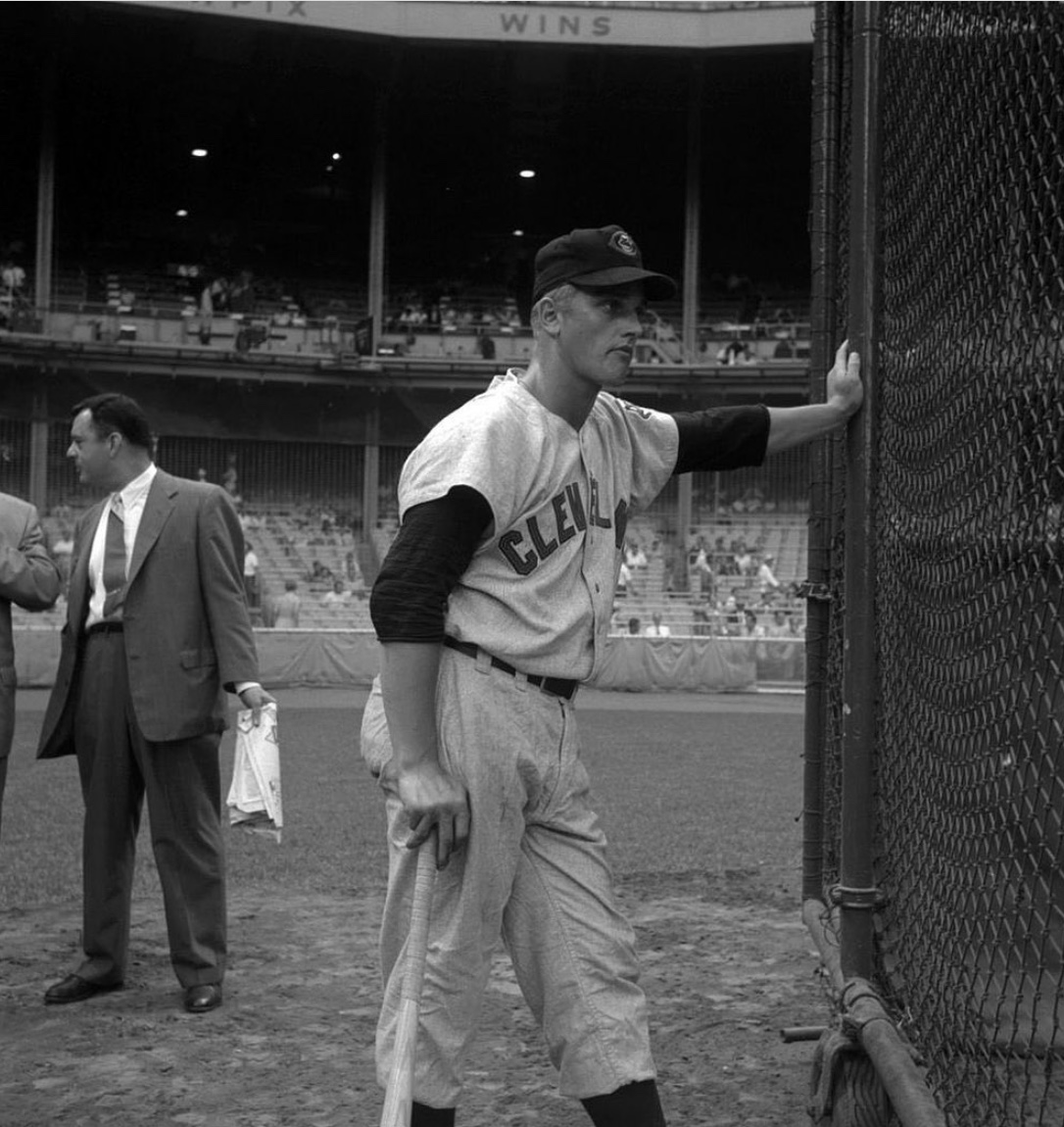

Instead of playing college football, Maris chose to sign with the Cleveland Indians right out of high school in 1953 for a $5,000 bonus. The left-handed-hitting Maris spent most of his early days in the minor leagues as a line-drive hitter, but he learned how to pull the ball under the tutelage of manager Jo Jo White while playing at Keokuk in 1954.

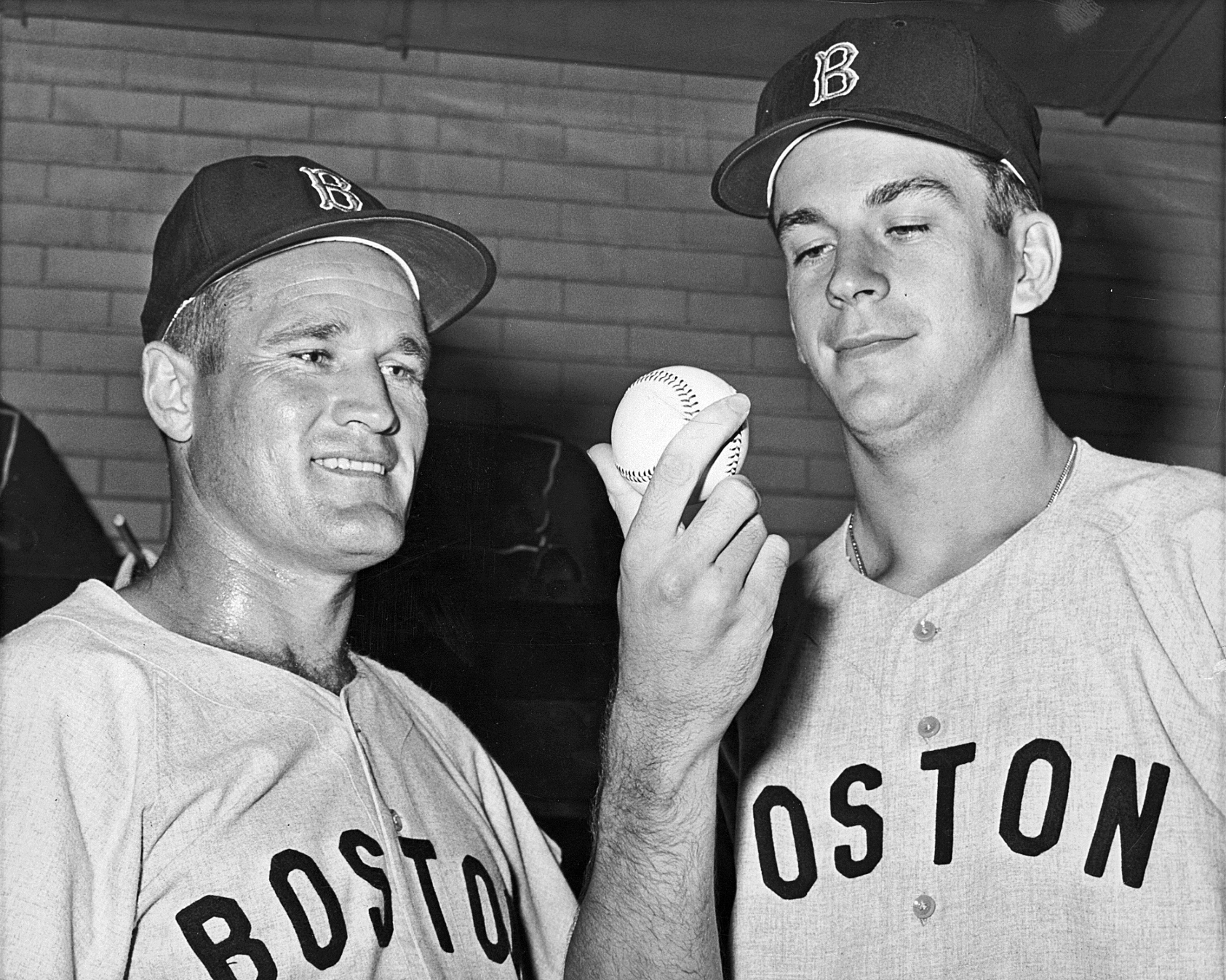

The 22-year-old outfielder broke into the major leagues in style with Cleveland in 1957, going 3-for-5 on Opening Day against the White Sox, before hitting his first big league home run the very next day – a grand slam game-winner, in the top of the 11th inning. Maris went on to hit 14 home runs in his rookie year, but he was traded to the Kansas City Athletics early in 1958 after alienating the Cleveland front office by refusing to play winter ball at the end of the previous season. The quiet and shy Maris thrived in Kansas City, hitting 28 home runs, driving in 80 runs, and scoring 87 others in his first year with his new team. Although injuries forced him to miss more than a month of the following season, the right-fielder played well enough to make the All-Star Team for the first time.

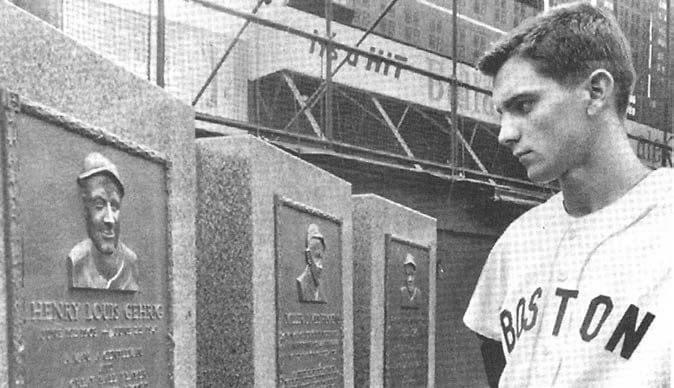

Maris was quite happy playing in the small mid-western town, and he fully expected to spend the remainder of his career there. The outfielder needed to alter his mindset, though, when he learned he had been traded to New York for a package of four players that included veterans Don Larsen and Hank Bauer, journeyman first baseman Marv Throneberry, and promising young outfielder/first baseman Norm Siebern. The Yankees actually had their eyes on Maris for quite some time before making the deal, believing that the outfielder’s compact yet powerful left-handed swing was perfectly suited to take advantage of Yankee Stadium’s short right field porch. However, the extremely forthright Maris immediately alienated much of the New York press corps upon his arrival in the big city by revealing to them the displeasure he felt over having to leave Kansas City.

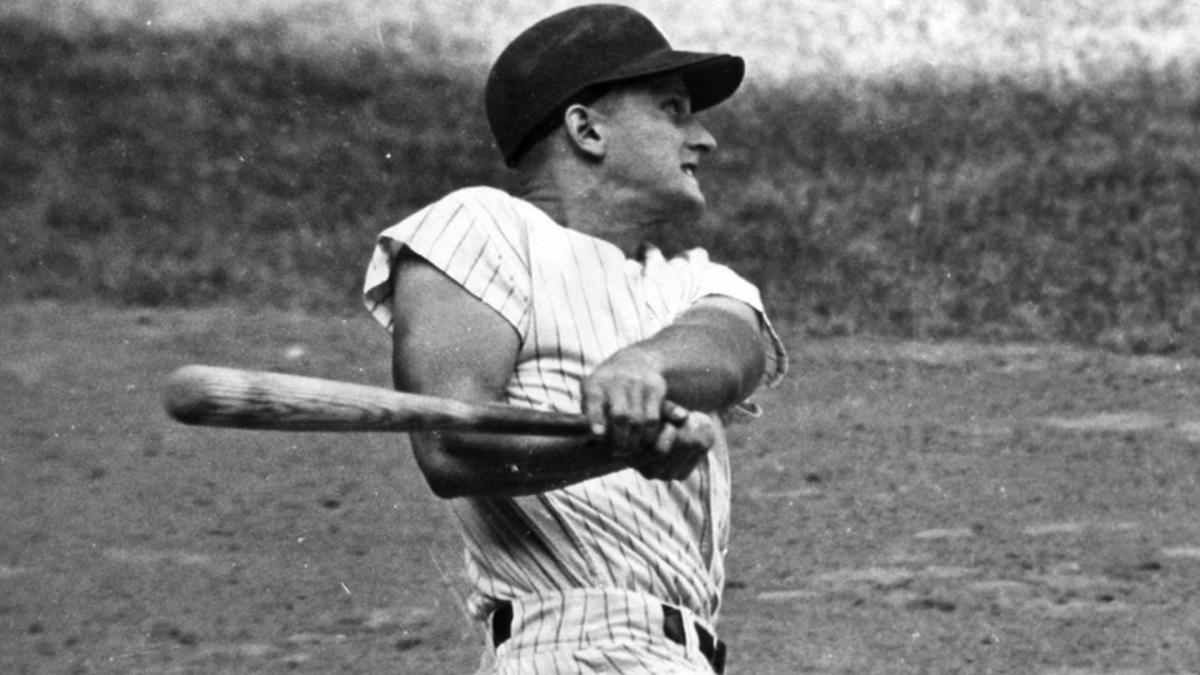

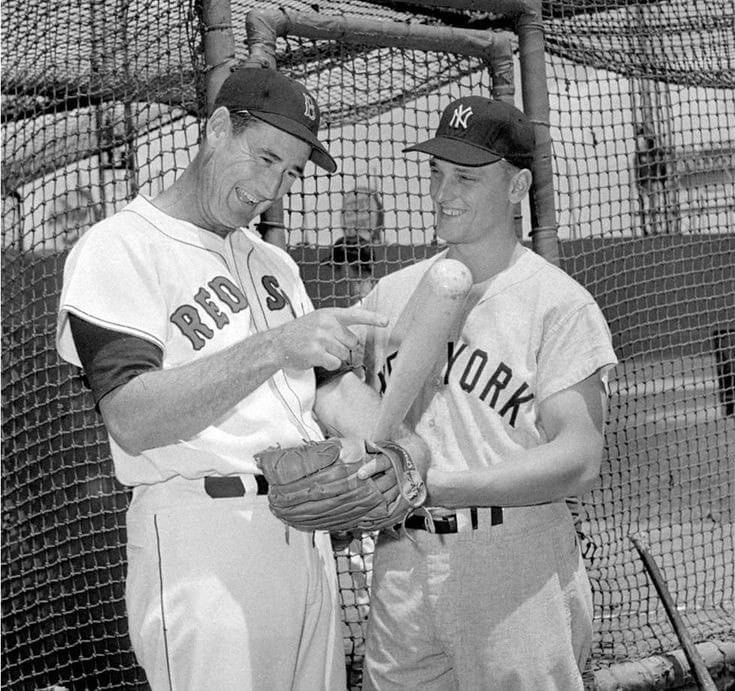

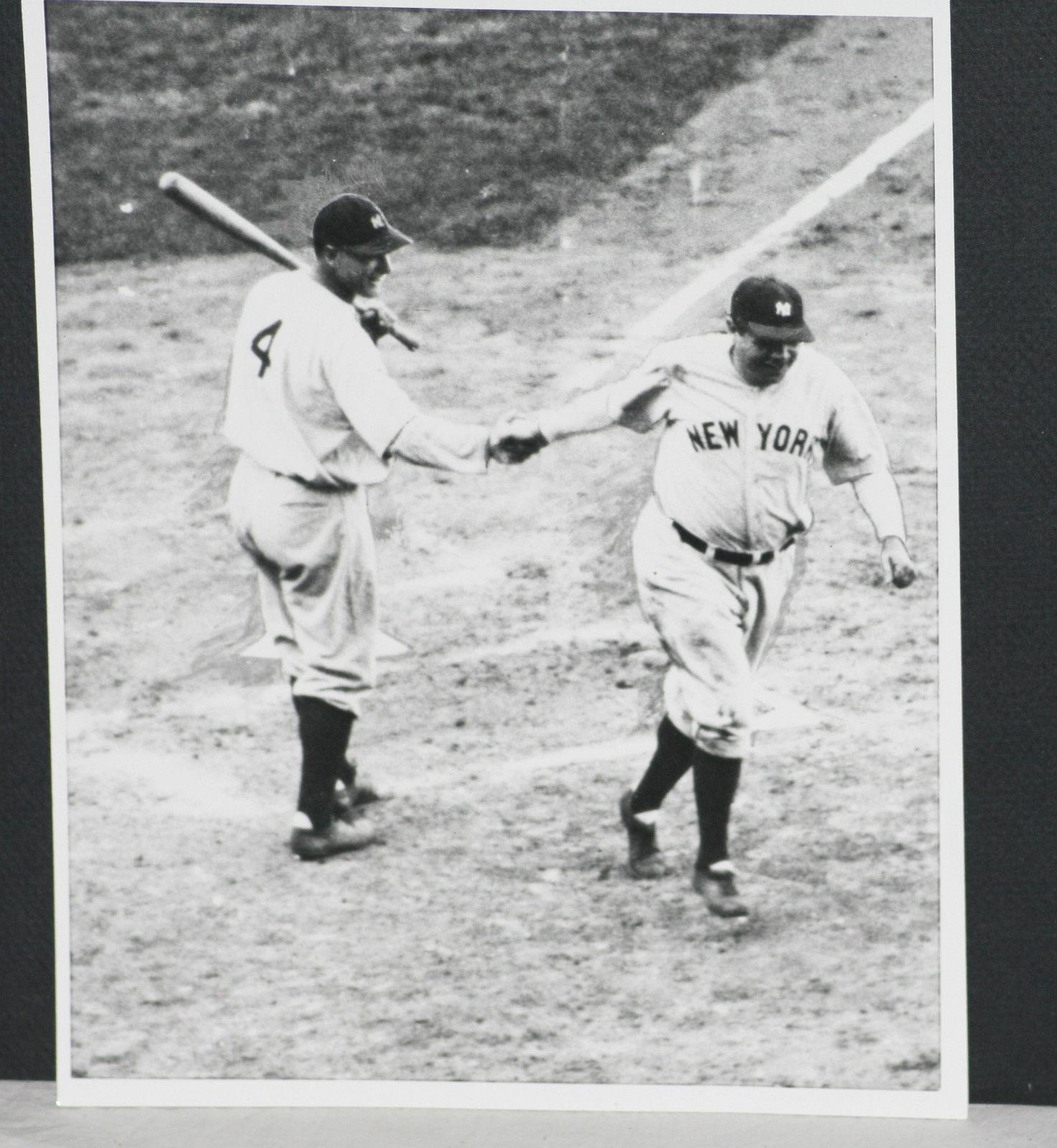

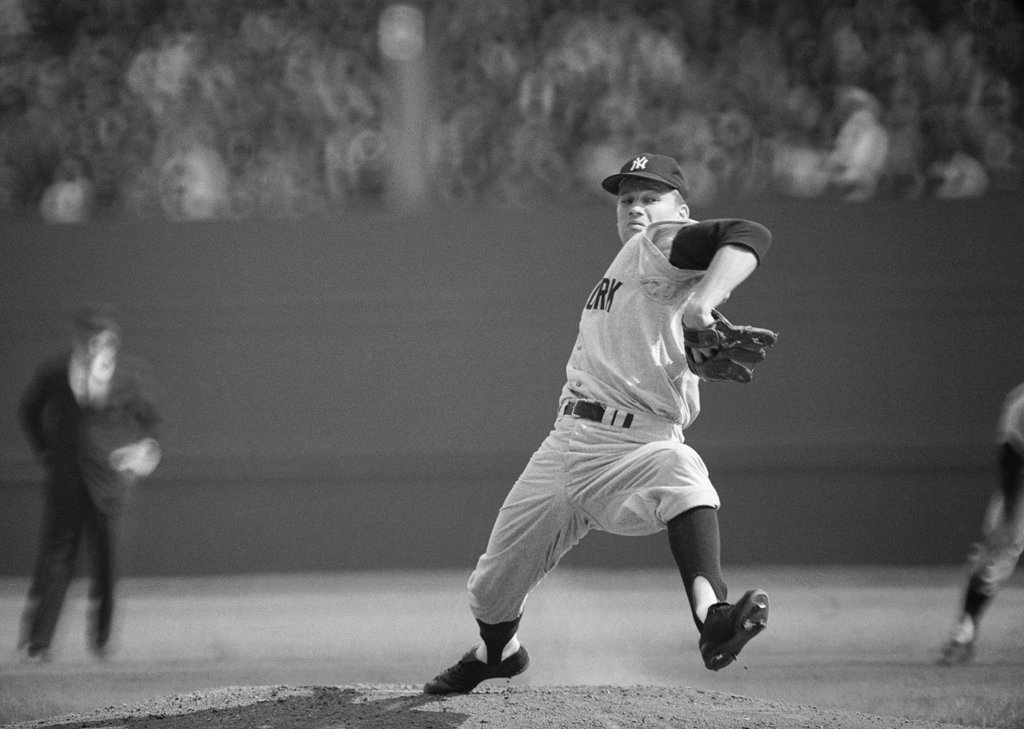

Nevertheless, the lopsided deal paid huge dividends for the Yankees, with their new right-fielder proving to be the perfect complement to Mickey Mantle in the middle of their batting order. Maris hit 39 home runs in his first year in pinstripes, finishing just one homer behind Mantle in the race for the league’s home run crown. The right-fielder topped the circuit with 112 runs batted in and a .581 slugging percentage, while also finishing second with 98 runs scored and winning a Gold Glove for his outstanding work in the outfield. Maris’ exceptional all-around year helped lead the Yankees to the first of five straight pennants and enabled him to edge out Mantle by three points in the league MVP voting.

Even though Maris’ contributions to the success of the team over the course of the season were undeniable, the right-fielder began to draw the ire of Yankee fans as he challenged Mantle for the league lead in home runs. Since they considered Mantle to be a “true” Yankee, fans of the team rooted for the centerfielder to win the home run crown, and correspondingly rooted against Maris whenever he stepped to the plate. Mantle subsequently became their hero, something he remained the rest of his career, while they begrudgingy accepted Maris as a necessary evil.

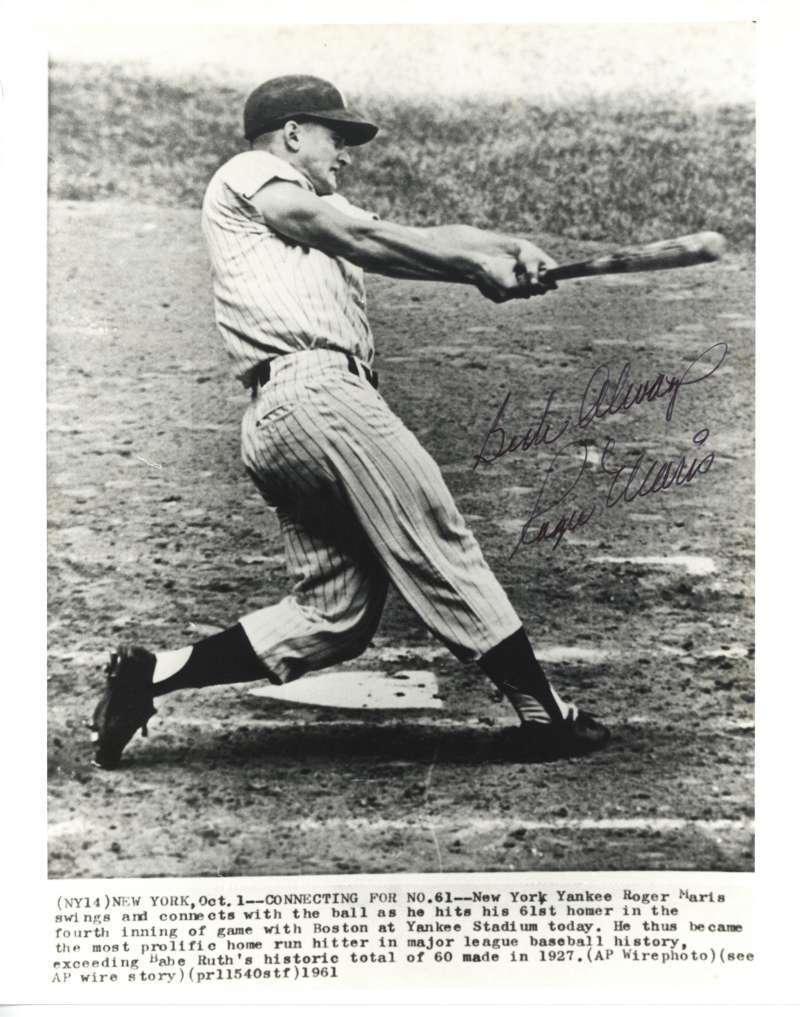

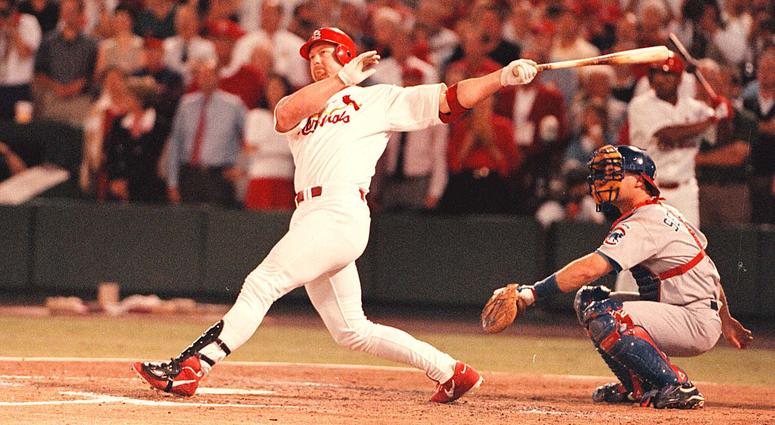

The feelings of the fans towards Mantle and Maris intensified the following year, when the two men waged an epic battle in the pursuit of Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record. Since the mark was held by a Yankee, New York fans felt that Mantle should be the one to break it. Furthermore, many people believed that Maris’ .269 batting average made him unworthy of eclipsing the great Ruth’s long-standing record. The fans subsequently cast Maris as an outsider and a usurper, and nothing he might have done from that point on would have been good enough to please them.

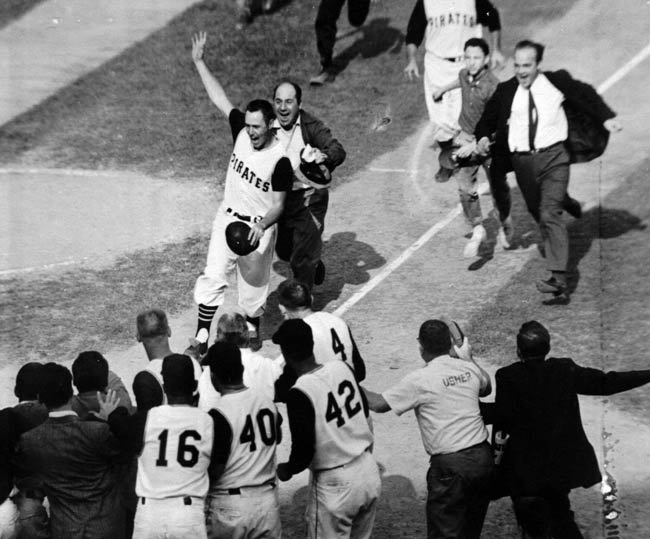

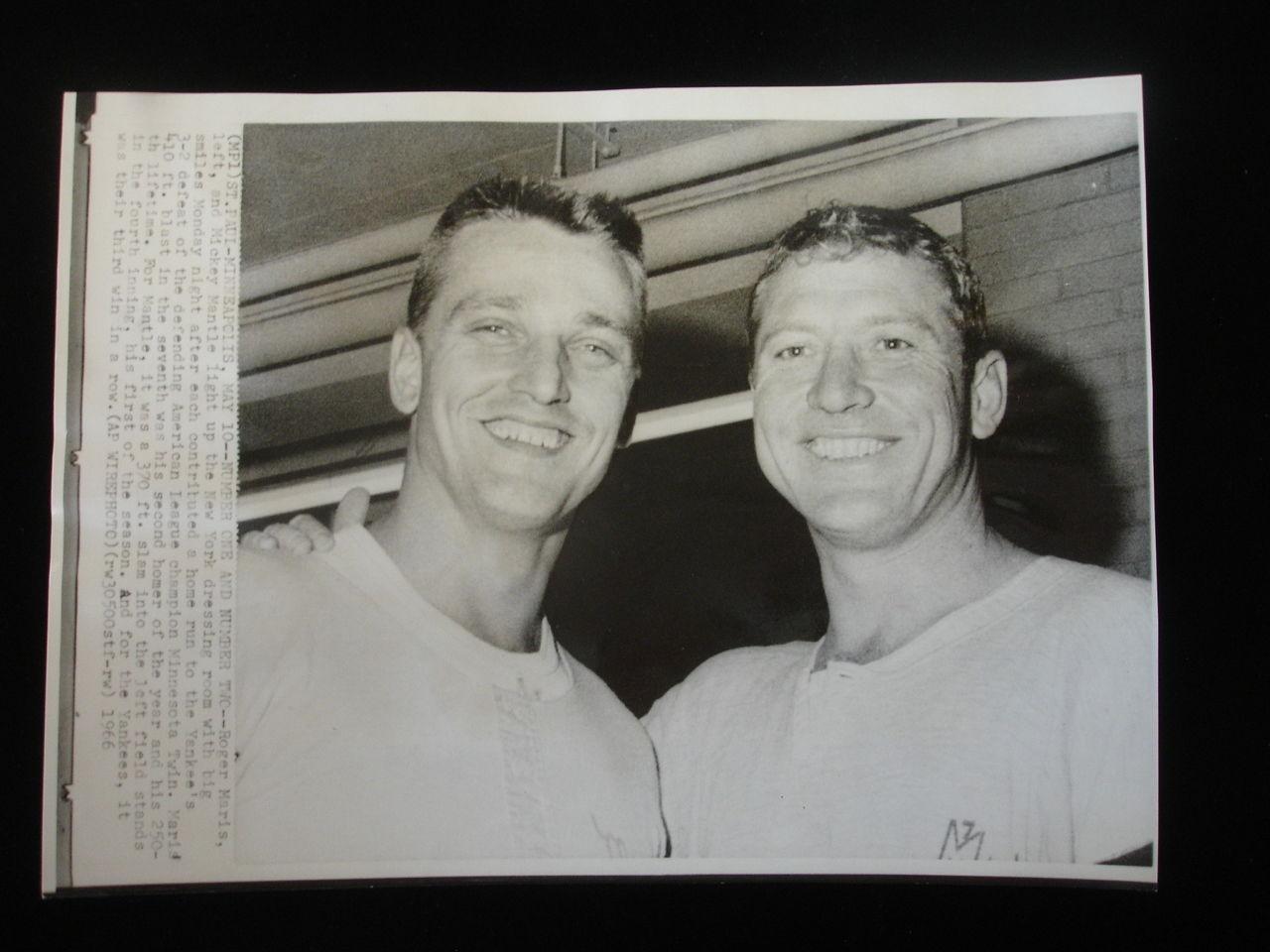

Displaying their indifference towards Maris, fewer than 15,000 fans showed up at Yankee Stadium on the season’s final day to see the slugger establish a new single-season record. Yet, the importance of the right-fielder to the success of the team was once again indisputable. Maris not only led the American League with 61 home runs, but he also topped the circuit with 142 runs batted in and 132 runs scored, en route to capturing his second consecutive MVP Award. However, many people considered his record-breaking performance to be something of a fluke, and when Maris hit “only” 33 home runs the following year, his critics felt vindicated, making him the object of their wrath. Still, there were other factors that greatly contributed to the lack of popularity Maris experienced with the fans of New York.

Adding to the furor surrounding Maris was the negative image the New York media created of him in the local newspapers. As Maris drew closer and closer to Ruth’s cherished record during the 1961 campaign, the pressure he endured intensified greatly, and the number of interview requests with which he had to comply became almost unbearable. Shy, quiet, unassuming, and uncharismatic, Maris never felt comfortable being in the spotlight. He tended to give short, honest answers to reporters’ questions, and, if he considered a question to be a stupid one, he said so. Maris felt extremely uncomfortable being questioned by large groups of reporters, and he conducted himself much better in one-on-one interviews. But, he always remembered if a reporter wrote something about him that he felt either misquoted or misrepresented him. In such instances, Maris invariably chose to stop dealing with the writer. As a result, some members of the media began portraying him as a sullen and moody snob.

To make matters worse, the Yankees found themselves completely unprepared for the media circus. As a result, they failed to assist Maris in any way, offering him nothing in the way of protection and setting no guidelines. As Maris said in later years, the Yankee public relations department essentially hung him out to dry. The stubborn and suspicious Maris simply did not know how to handle his new-found celebrity. As he grew increasingly suspicious and irritable over the course of the season, he granted fewer and fewer interview requests. However, when he snubbed powerful and influential sportswriter Jimmy Cannon, the latter wrote a scathing article on Maris that caused much of the public to view the outfielder in an unfavorable light.

Therefore, Yankee fans found it quite easy to question the severity of Maris’ injuries. The right-fielder broke his hand sliding into home plate in June of 1965, causing him to lose much of the strength in the hand. X-rays taken failed to reveal the break, though, prompting the Yankees to subsequently list Maris on their injury report as day-to-day. As Maris continued to sit on the bench unable to play, fans of the team began to question his heart and desire. The already antagonistic press literally added insult to injury by also questioning the outfielder’s mettle. Maris later revealed that he also felt club officials minimized the severity of the injury, and that they sometimes acted as if they, too, considered him well enough to play.

Another X-ray was finally taken that showed a small fracture of a bone in the hand. Although the hand was surgically repaired at the end of the season, the damage to Maris’ reputation was irreparable. His tenuous relationship with the fans, the media, and the Yankee front office worse than ever, Maris spent his remaining time in New York being hung in effigy.

However, Maris’ teammates had a different perception of the man. Bobby Richardson, who played with Maris for seven seasons, said, “He was the most reserved, quiet individual I think I ever knew, so the press’ portrayal of him was not the real Roger Maris.”

Clete Boyer said of his former teammate, “The guy was a great player. They like to say that 1961 was a fluke, but Roger hit 39 homers and was the American League MVP in 1960. Not too many stiffs become back-to-back MVPs.”

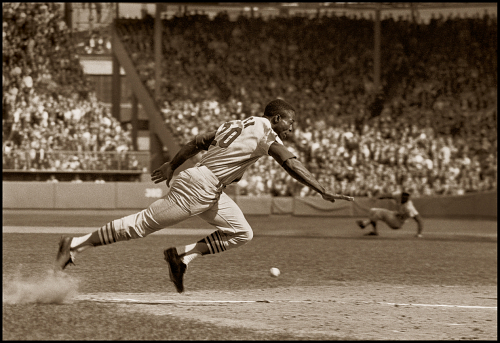

Whitey Ford discussed Maris in his book Few And Chosen: “He was fast, and he was a great base-runner with excellent instincts when it came to taking the extra base. And he was as good as I’ve seen at breaking up the double play.”

Moose Skowron said of Maris: “He could run, he could throw, he could hit…great defensive outfielder. He did the little things to win a ballgame…and the writers crucified him…no way.”

In speaking of Maris, Mickey Mantle said, “When people think of Roger, they think of the 61 home runs, but Roger Maris was one of the best all-around players I ever saw. He was as good a fielder as I ever saw, he had a great arm, he was a great base-runner – I never saw him make a mistake on the bases – and he was a great teammate. Everybody liked him.”

Perhaps Gil McDougald said it best when he said, “Roger was the everyday ballplayer that every manager would like to see on a ball club.”

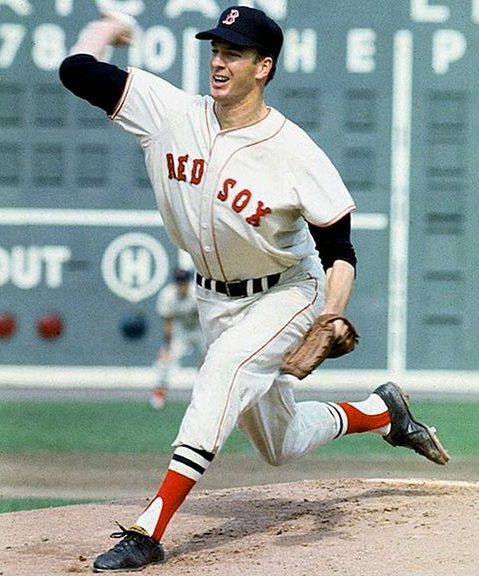

Maris was also a winner. He played in more World Series than any other player in the 1960s. In addition to his five World Series appearances with the Yankees, he helped the St. Louis Cardinals capture both the 1967 and 1968 pennants, after being traded to the team from New York for journeyman third baseman Charley Smith. Maris’ outstanding play during the 1967 World Series helped the Cardinals defeat the Boston Red Sox in seven games. The outfielder batted .385, with 10 hits and seven runs batted in during the Fall Classic.

Maris spent two years in St. Louis before retiring at the conclusion of the 1968 campaign. He ended his career with 275 home runs, 850 runs batted in, 826 runs scored, a .260 batting average, and a .345 on-base percentage. In addition to playing for seven pennant-winning teams and three world championship clubs, Maris earned four selections to the American League All-Star Team.

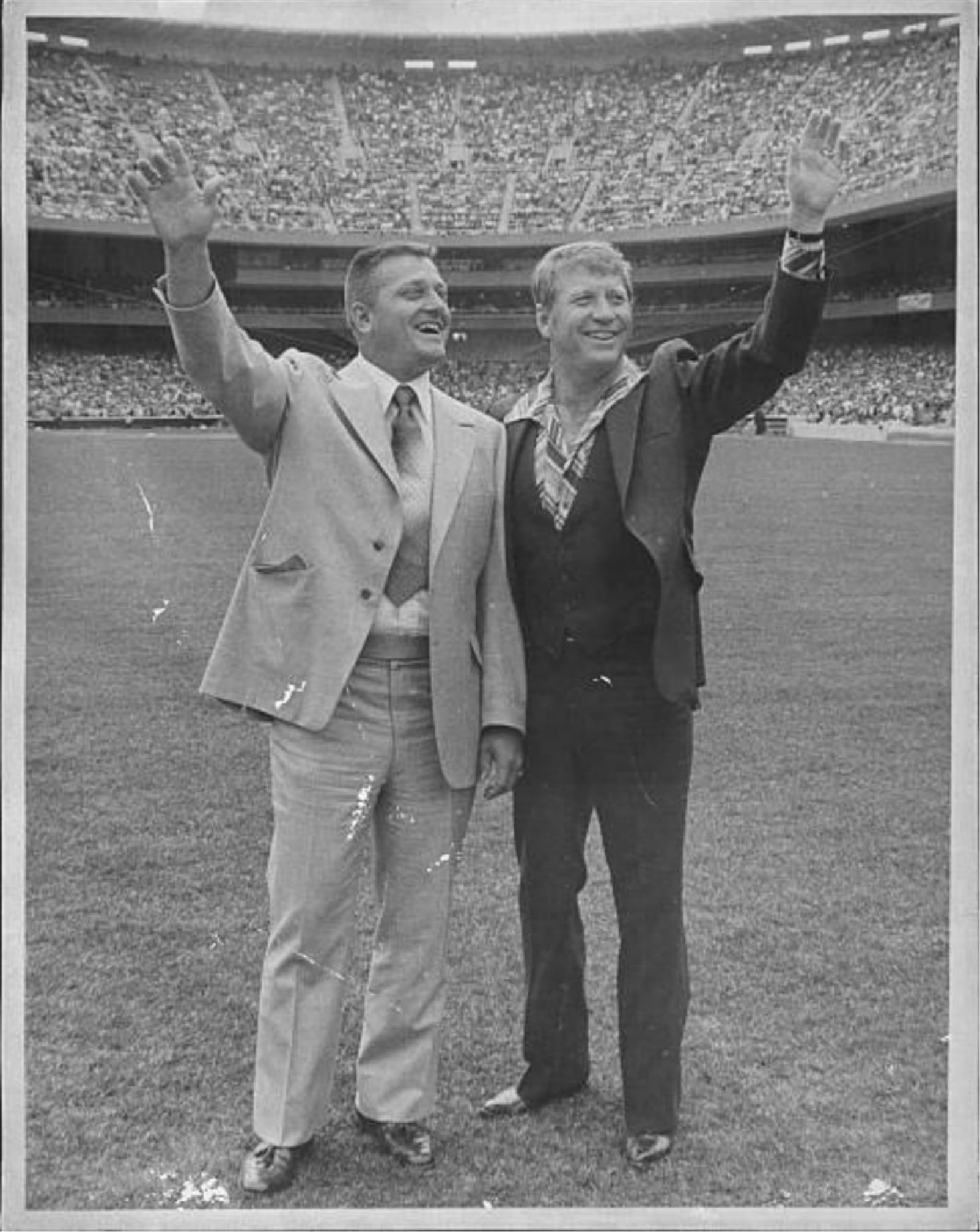

After leaving baseball, Maris owned a Budweiser Beer distributorship in Gainesville, Florida, where he resided following his playing career. He stayed away from Yankee Stadium for more than a decade, declining numerous invitations to Old-Timer’s Day. However, he finally agreed to come back when George Steinbrenner offered to donate money to build a stadium in Gainesville. Maris made his return on Opening Day, 1978, fittingly raising the Yankees’ 1977 championship flag with Mickey Mantle and being given a standing ovation when he received his introduction to the crowd.

The fans at Yankee Stadium again cheered Maris loudly when he returned to the ballpark in 1984 to have his old number 9 retired, along with the number 32 formerly worn by his deceased teammate Elston Howard. Maris displayed the kind of emotions during his acceptance speech he previously failed to show the public; the sort of emotions Yankee fans had longed to see from him during his tenure with the team.

Roger Maris passed away just one year later from lymph-gland cancer. Shortly before his death on December 14, 1985, he said, “I always came across as being bitter. I’m not bitter. People were very reluctant to give me any credit. I thought hitting 60 home runs was something. But everyone shied off. Why, I don’t know. Maybe I wasn’t the chosen one, but I was the one who got the record.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.