VINTAGE BASEBALL MEMORABILIA

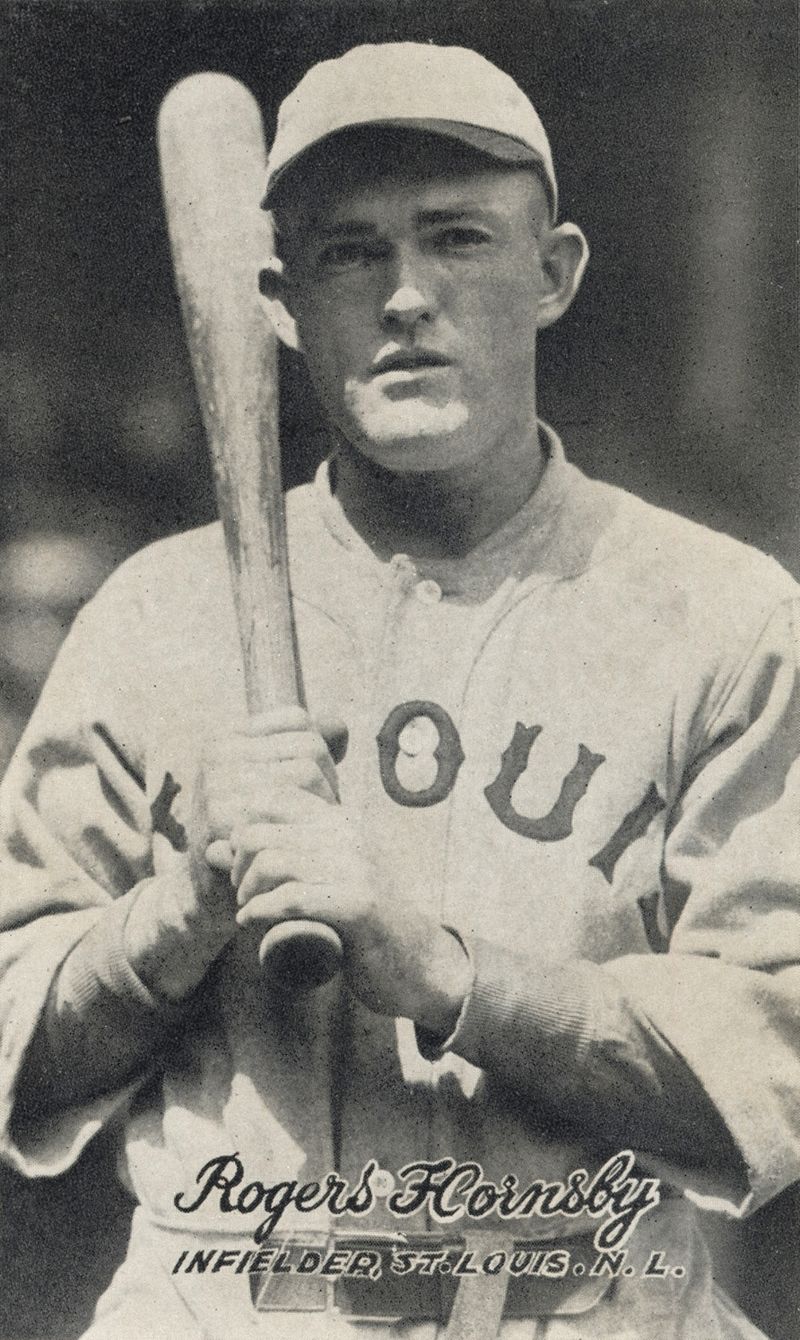

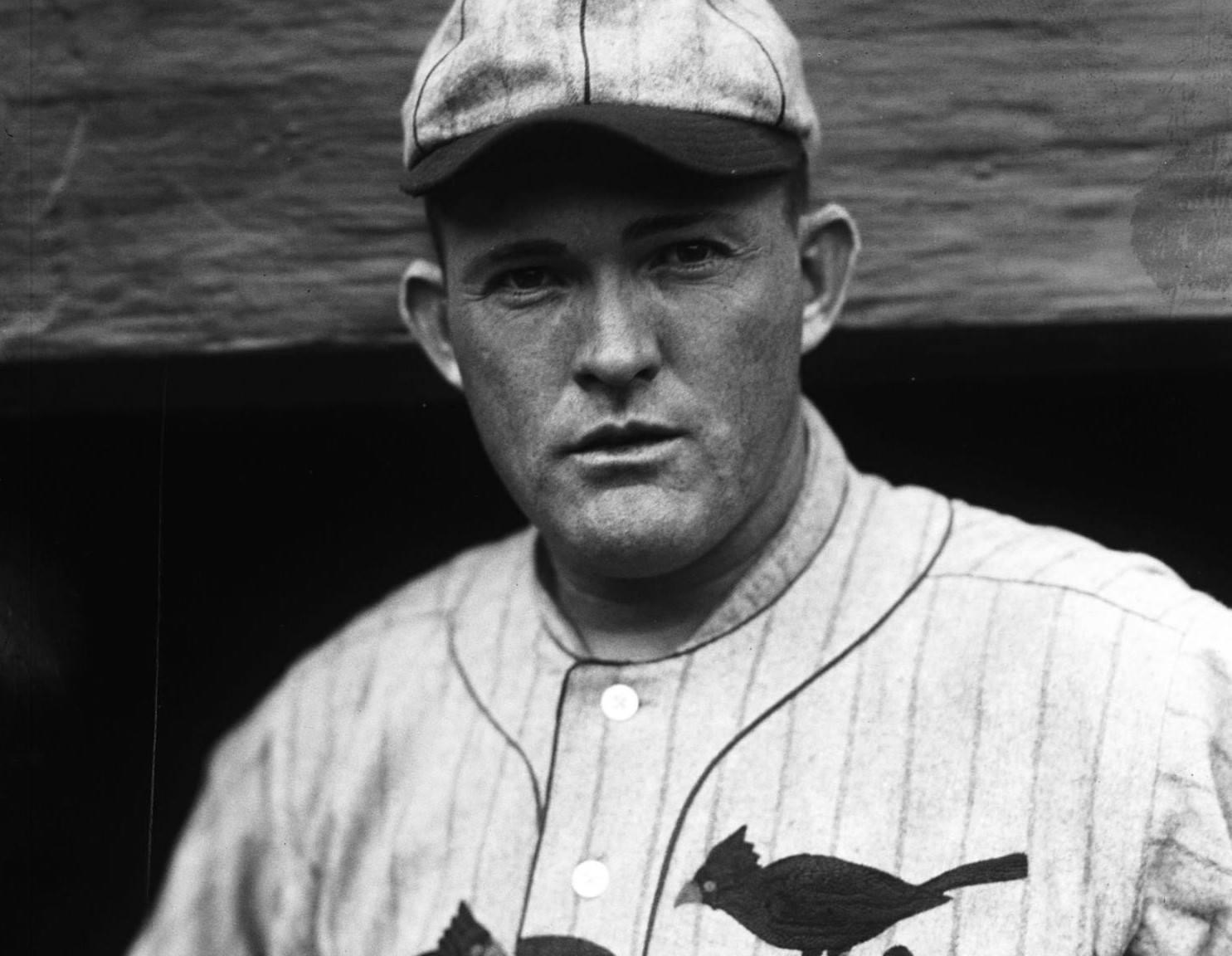

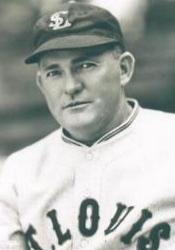

Rogers Hornsby Essentials

Positions: Second Baseman, Shortstop and Third Baseman

Bats: Right Throws: Right

Height: 5-11 Weight: 175

Born: April 27, 1896 in Winters, TX

Died: January 5, 1963 in Chicago, IL

Buried: Hornsby Bend Cemetery, Hornsby Bend, TX

High School: Northside HS (Fort Worth, TX)

Debut: September 10, 1915

vs. CIN 2 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: July 20, 1937

vs. NYY 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1942. (Voted by BBWAA on 182/233 ballots)

No induction ceremony in Cooperstown held (until 2013).

View Rogers Hornsby’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Rogers Hornsby

Nicknames: Rajah

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1915

Sam Rice

Rogers Hornsby

Joe Judge

George Sisler

Dave Bancroft

Dazzy Vance

Charlie Jamieson

George Kelly

Baby Doll Jacobson

The Rogers Hornsby Teammate Team

C: Gabby Hartnett

1B: George Sisler

2B: Billy Herman

3B: Fred Lindstrom

SS: Travis Jackson

LF: Kiki Cuyler

CF: Hack Wilson

RF: Chick Hafey

SP: Jesse Haines

SP: Bill Doak

SP: Pete Alexander

SP: Dizzy Dean

SP: Burleigh Grimes

RP: Dazzy Vance

M: Branch Rickey

Notable Events and Chronology for Rogers Hornsby Career

Biography

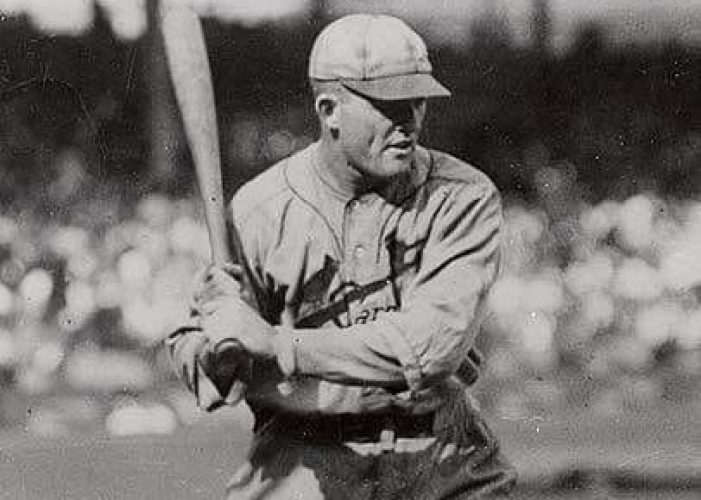

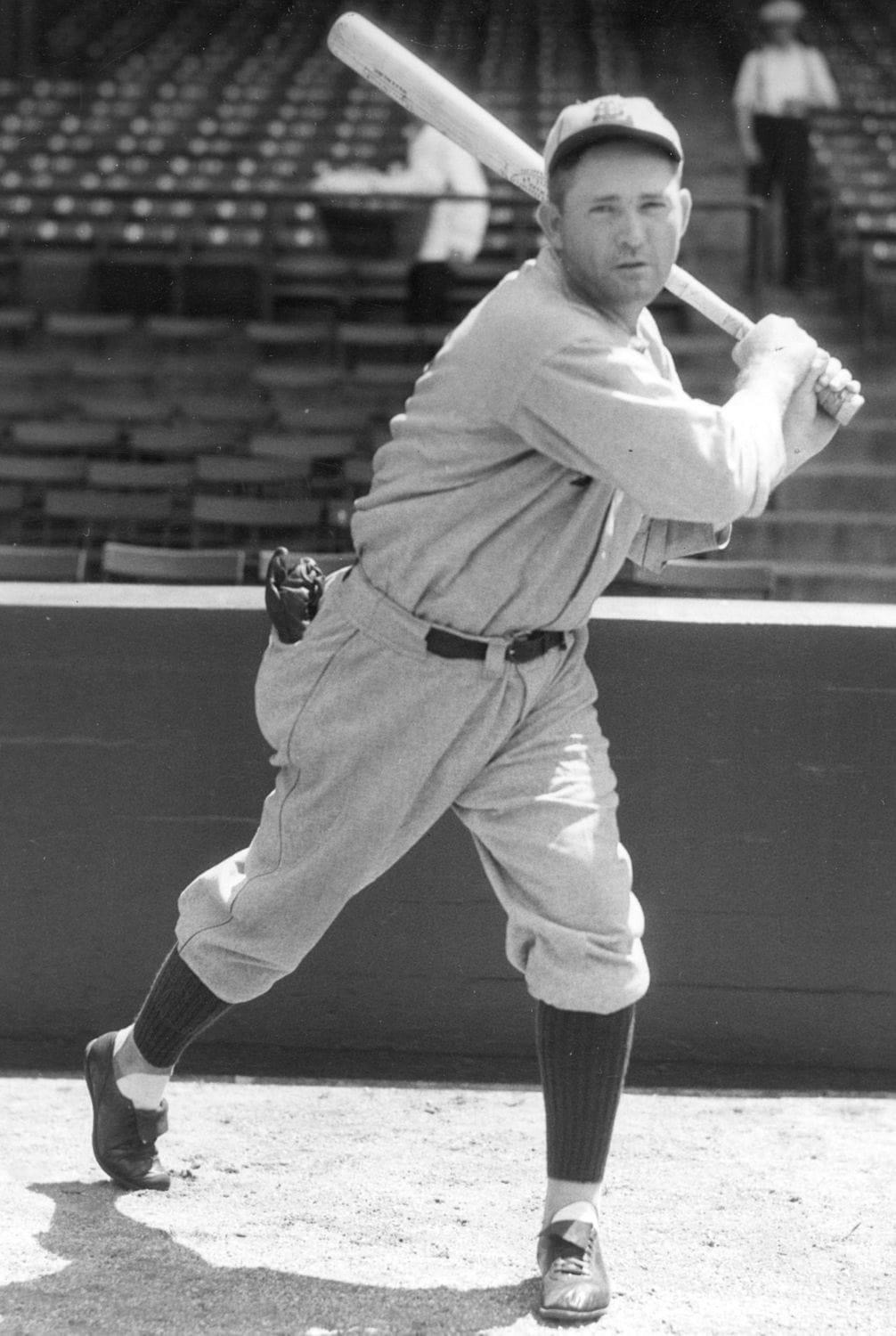

The winner of two National League triple crowns and the owner of the second highest career batting average in major league history, Rogers Hornsby is considered by most baseball historians to be the greatest righthanded hitter ever to play the game. Easily the most prolific offensive second baseman of all time, Hornsby dominated the National League during the 1920s, much as Babe Ruth ruled the American League. Hornsby won two Most Valuable Player Awards during the decade, captured seven batting titles, and led the league in on-base and slugging percentage eight times each. Perhaps his most remarkable achievement, though, is that he batted a combined .402 from 1921 to 1925.

Rogers Hornsby Biography

Born in Winters, Texas on April 27, 1896, Rogers Hornsby got his somewhat unusual first name from his mother Mary, whose maiden name was Rogers. After his father, Aaron Edward Hornsby, died in 1898, Rogers moved with the rest of his family to Fort Worth, Texas. Although he attended Northside High School in Fort Worth, Hornsby already knew that a career in the major leagues awaited him. After competing against grown men by the time he was 15, Hornsby spent a few years playing semi-pro ball, before beginning his minor-league career in the Texas-Oakland League in 1914. Hornsby was discovered the following year by a St. Louis Cardinals scout, who purchased his contract for $500.

The slightly-built Hornsby wasn’t much of a hitter in the minor leagues. Standing 5’11” tall and weighing only 155 pounds, he displayed little power at the plate, and he failed to hit for a particularly high batting average. Called up to St. Louis late in 1915, Hornsby batted only .246 in his 57 official at-bats. However, after observing Hornsby, Cardinals manager Miller Huggins suggested he put on some weight. The young infielder heeded Huggins’ advice and spent the winter of 1915 working on his uncle’s farm. After reporting to spring training in 1916 some 20 pounds heavier, Hornsby won a starting job in the St. Louis lineup. Splitting his time primarily between third base and shortstop, the 20-year-old Hornsby batted .313 and finished among the league leaders in triples and both on-base and slugging percentage.

Hornsby spent each of the next two seasons at shortstop for the Cardinals, performing somewhat erratically in the field but developing into one of the National League’s better hitters. He finished second in the league in batting average and on-base percentage in 1917, while topping the circuit in triples, slugging percentage, and total bases. His numbers fell off somewhat during the war-shortened 1918 campaign, but Hornsby had another solid season in 1919. Splitting his time between all four infield positions, Hornsby placed among the league leaders in batting average, hits, total bases, on-base percentage, and slugging percentage.

Twenty-four years of age by the start of the 1920 season and an additional 20 pounds heavier, Hornsby had matured both physically and mentally. Ready for his breakout season, he moved to second base, a position he manned the remainder of his career. Feeling more comfortable in the field, Hornsby began his onslaught on National League pitchers by hitting .370, to capture the first of his six consecutive batting titles. He also topped the circuit for the first of three straight times in runs batted in, hits, doubles, and total bases, and for the first of six straight times in both on-base and slugging percentage.

The National League began using a livelier ball in 1921, and power numbers increased dramatically throughout the senior circuit. Hornsby was no exception, more than doubling his previous seasonal high in home runs by hitting 21 long balls, to finish second in the league. While the second baseman placed second in homers, he topped the circuit with 126 runs batted in, 131 runs scored, 18 triples, 44 doubles, 235 hits, a .397 batting average, 378 total bases, a .458 on-base percentage, and a .639 slugging percentage. Hornsby was even more dominant the following year, leading the league in nine different offensive categories and capturing the first of two triple crowns by finishing first with 42 home runs, 152 runs batted in, and a .401 batting average. In arguably his greatest season, Hornsby not only established career highs in homers and RBIs, but, also, in hits (250) and total bases (450).

Injuries limited Hornsby to 107 games in 1923, but he still managed to lead the league in batting for the fourth straight year with a mark of .384. Fully healthy again in 1924, Hornsby posted the highest single-season batting average of the modern era by hitting a remarkable .424. He also hit 25 home runs, drove in 94 runs, and led the league with 121 runs scored, 227 hits, 43 doubles, a .507 on-base percentage, and a .696 slugging percentage, en route to finishing a close second to Dodger hurler Dazzy Vance in the MVP balloting. Hornsby claimed his first MVP trophy the following year when he became the only player in National League history to win two triple crowns. In addition to topping the circuit with 39 home runs, 143 runs batted in, and a .403 batting average, the second sacker finished first with a .489 on-base percentage, a .756 slugging percentage, and 381 total bases.

Hornsby’s incredible success as a hitter could be attributed to a number of factors. In addition to possessing amazing natural ability, Hornsby employed a near-fanatical training regimen that not only included abstinence from smoking and drinking, but that also prevented him from either reading or going to the movies during the season for fear of ruining his batting eye. A perfectionist at the plate, Hornsby rarely swung at bad pitches, and he always stood in the far back corner of the batter’s box and strode into the pitcher’s delivery with a perfectly level swing. Opposing teams often tried to pitch him low and away, but his diagonal stride afforded him excellent plate coverage. A remarkably consistent hitter, Hornsby posted a lifetime .359 batting average at home, while hitting .358 on the road during his career. He made such an impression on Ted Williams that The Splendid Splinter stated in his autobiography, My Turn At Bat, that Hornsby was the greatest hitter for average and power in the history of baseball.

One of the more overlooked aspects of Hornsby’s game was his ability as a baserunner. Blessed with outstanding running speed, he often turned singles into doubles, and doubles into triples. In fact, Hornsby accumulated 30 inside-the-park home runs over the course of his career. In a January 8, 1963 article in the Chicao American, Hall of Fame manager Al Lopez said of Hornsby, “he was one of the speediest men we ever had in baseball.”

Long after Hornsby’s playing days were over, he was often compared to a young Mickey Mantle in terms of running speed. Hall of Fame third baseman Pie Traynor, who saw both men play, insisted that Hornsby would have beaten Mantle to first base from the right hand batter’s box.

While no one ever questioned Hornsby’s greatness as a hitter, the second baseman has often been criticized through the years for his defense. Generally considered to be a mediocre fielder at best, Hornsby frequently struggled with pop-ups, and he committed as many as 52 errors while playing shortstop for the Cardinals in 1917. Still, a reporter for the Washington Post described Hornsby in 1918 as “the outstanding fielding shortstop in the western circuit of the National League and perhaps the finest fielding shortstop in the entire league.” After moving to second base in 1920, Hornsby led the league in putouts, assists, and double plays. In an August 26, 1925 article in the Los Angeles Times, Hall of Fame shortstop and manager Hughie Jennings described Hornsby as one of the best-fielding second basemen in the game. And his average of 3.31 assists per-game is the seventh highest of any second baseman in baseball history.

As much as Hornsby’s fielding ability has come into question through the years, the quality of his character has perhaps been scrutinized even more closely. Most accounts of the time reveal Hornsby to be cold, contentious, heartless, and brutally frank. His chief interest was in winning, and he didn’t hesitate to criticize anyone, be it a teammate, an opponent, a manager, or an owner. One writer characterized Hornsby as “a liturgy of hatred,” and according to baseball writer Fred Lieb, Hornsby confessed to being a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

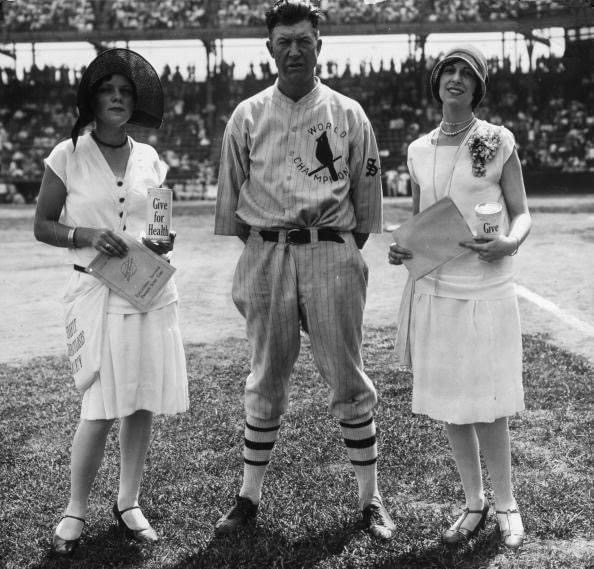

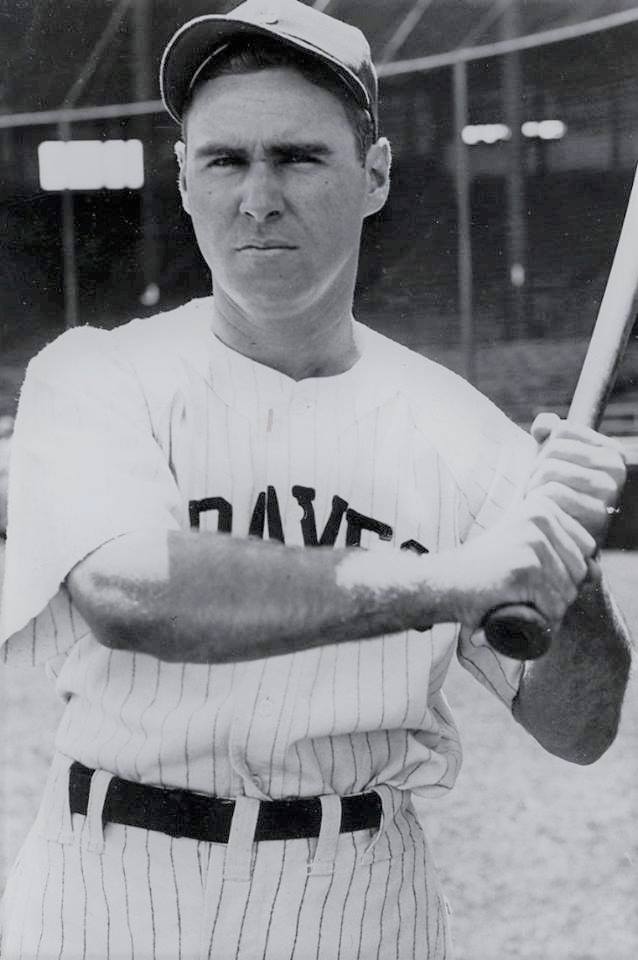

Hornsby’s difficult manner helps to explain the nomadic existence he led during the second half of his career. After leading the Cardinals to the world championship in 1926 despite batting only .317, Hornsby was traded to the Giants for Frankie Frisch by St. Louis owner Sam Breadon following a contract dispute between the latter and his argumentative player/manager. Hornsby had a big year for the Giants in 1927, hitting 26 home runs, driving in 125 runs, scoring 133 others, and batting .361. Nevertheless, he was dispatched to Boston at season’s end after quarreling with the Giants’ equally belligerent manager John McGraw. The second baseman had another outstanding season for the Braves, batting a league-leading .387 in 1928, but he quickly wore out his welcome there as well. Hornsby joined the Chicago Cubs in 1929, leading his new team to the pennant and capturing league MVP honors for the second time by hitting 39 homers, knocking in 149 runs, batting .380, compiling 229 hits, and topping the circuit with 156 runs scored, 409 total bases, and a .679 slugging percentage.

The 1929 campaign was Hornsby’s last as a full-time player. A broken leg kept him out of Chicago’s lineup for all but 42 games the following season, one in which he replaced Joe McCarthy as the team’s manager. Serving as player/manager in 1931, the 35-year-old Hornsby batted .331 and compiled a league-leading .421 on-base percentage in 100 games. However, after appearing in only 19 games for the Cubs in 1932 due to a heel spur, Hornsby was fired as manager and subsequently traded back to his original team, the St. Louis Cardinals. He split the 1933 season between the Cardinals and the St. Louis Browns, ending his career with the Browns in 1937.

Rogers Hornsby retired from the game with 301 home runs, 1,584 runs batted in, 1,579 runs scored, 2,930 hits, a .358 lifetime batting average, a magnificent .434 on-base percentage, and a .577 slugging percentage. Only Ty Cobb (.367) posted a higher lifetime batting average. Hornsby hit as many as 39 home runs three times, drove in more than 100 runs five times, scored more than 100 runs six times, accumulated more than 200 hits seven times, and batted over .400 on three separate occasions. In addition to his seven batting titles, Hornsby led the league in home runs and triples twice each, runs batted in, hits, and doubles four times each, runs scored five times, and on-base and slugging percentage nine times each. Hornsby holds 20th century National League records for highest single-season batting average (.424), on-base percentage (.507), and slugging percentage (.756), and most total bases (450). Hornsby led all National League players in home runs, runs batted in, and batting average during the 1920s, making him one of onlyfour players in baseball history to win a “decade” triple crown. (Honus Wagner, Ted Williams, and Albert Pujols were the others).

After his playing career was over, Hornsby had numerous stints as both a manager and as a scout. However, his autocratic style of managing and his critical nature made it extremely difficult for Hornsby to relate to players. After serving briefly as a scout for the fledgling New York Mets in 1962, Hornsby died of a heart attack in 1963 shortly after undergoing cataract surgery.

In spite of Roger Hornsby’s contentious nature, his reputation as a truly great baseball player remains unsullied. While Stan Musial still reigned supreme in the city of St. Louis during the 1950s, former Cardinal owner Sam Breadon, who was responsible for once trading Hornsby to the Giants, was asked if Stan The Man was his greatest player ever.

Breadon considered the question for a few moments before responding, “No, I couldn’t say that. There was Hornsby.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Strange Things

Though he is often lumped with Ted Williams as a manager because he had a hard time relating to players and posted a poor record, Hornsby was not a bad manager. His lifetime percentage of .463 as manager includes several games at the helm of the measly Browns. When he had a good team Hornsby did well, winning pennants with the Cards and the Cubs. He could be a devil at times, however, and many of his players hated him. Once. while managing the minor leagues, Hornsby went into the shower and urinated on a pitcher who had been hit hard in the game that day.

Best Season, 1924

Hornsby went hitless in just 24 games as he batted .424 to win another batting title. That season, the only pitcher to hold him hitless three times was Boston’s Johnny Cooney, a crafty left-hander. In 1922, at the age of 26, Hornsby played nearly every day, batted .401, slugged 42 homers (rarified air that only Babe Ruth had reached to that point), and collected 250 hits (never going more than two games without a hit). He ran off a 33-game hitting streak, banged out 102 extra-base hits and 450 total bases to go along with 152 RBI and 140 runs scored. It remains one of the most productive offensive seasons in baseball history.

Awards and Honors

1922 NL Triple Crown

1925 NL MVP

1925 NL Triple Crown

1929 NL MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1926 World Series

1929 World Series

Description

Hornsby had few vices, but gambling was one of them. In 1927 two separate bookies approached the commissioner’s office to complain that Hornsby owed them several thousands of dollars for bets he’d placed on horses who had lost. Hornsby’s first stsint as Browns’ manager was probably ended becasue of his gambling problem.

Factoid

On opening day of the 1924 season, Rogers Hornsby went two-for-five against Vic Aldridge of the Chicago Cubs. With one game on his ledger for the season, Hornsby was hitting .400. He actually improved on that mark the rest of the way, huitting .424 to win the batting title!

Minor League Experience

1914: Hugo-Denison (Texas/Oklahoma League)

1915: Denison (Western Association)

1938: Baltimore Orioles (International Association)

1938: Chattanooga Lookouts (Southern League)

1940: Oklahoma City (Texas League)

Post-Season Notes

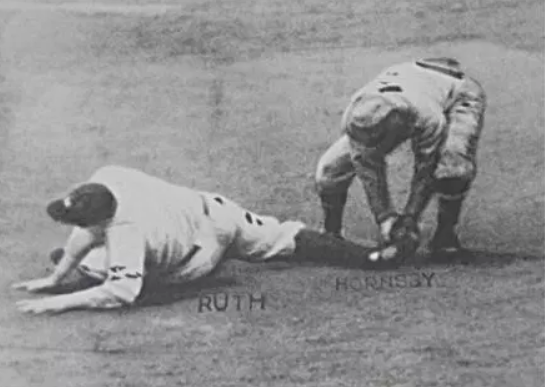

Hornsby had modest success in the post-season, hitting .245 in 12 World Series games, with just three extra-base hits… Hornsby led the Cardinals to their first World Series title in 1926 as their player/manager. Playing second base, Hornsby hit .317 with 11 homers and 93 RBI. It was a dramatic dropoff from his 1925 output (.403/39/143), but he guided the club through a tight pennant race and a thrilling seven-game Series win over Babe Ruth and the Yankees.

Feats: Hornsby won the National League Triple Crown in 1925 and 1929… Hornsby collected at least one extra-base hit in 11 straight games in August of 1924 with the Cardinals. In 1928, from May 27 (first game of DH) through June 9 (first game of DH), he collected an extra-base hit in 12 consecutive games. During that streak, he clubbed eight homers and nine doubles.

Notes

For a five-year stretch, Hornsby was a hitting machine. From 1921 to 1925 he batted .402 with a .690 slugging percentage and a .474 OBP. He averaged 216 hits, 123 runs, 41 doubles, 13 triples, 29 home runs, and 120 RBI per season during that span.

Hitting Streaks

33 games (1922)

33 games (1922)

Transactions

December 20, 1926: Traded by the St. Louis Cardinals to the New York Giants for Frankie Frisch and Jimmy Ring; January 10, 1928: Traded by the New York Giants to the Boston Braves for Shanty Hogan and Jimmy Welsh; November 7, 1928: Traded by the Boston Braves to the Chicago Cubs for Socks Seibold, Percy Jones, Lou Legett, Freddie Maguire, Bruce Cunningham, and $200000 cash.

Hornsby is the greatest player in baseball history who moved around as much as he did. Perhaps only Rickey Henderson can be considered the greatest at his position despite having bounced around to so many teams.

The Rajah at His Best

Here’s a breakdown of how well Hornsby hit against each team in the National League during the 1924 season when he hit .424:

vs. Braves (36-for-75, .480)

vs. Giants (34-for-78, .436)

vs. Phillies (35-for-82, .427)

vs. Dodgers (39-for-92, .424)

vs. Reds (30-for-73, .411)

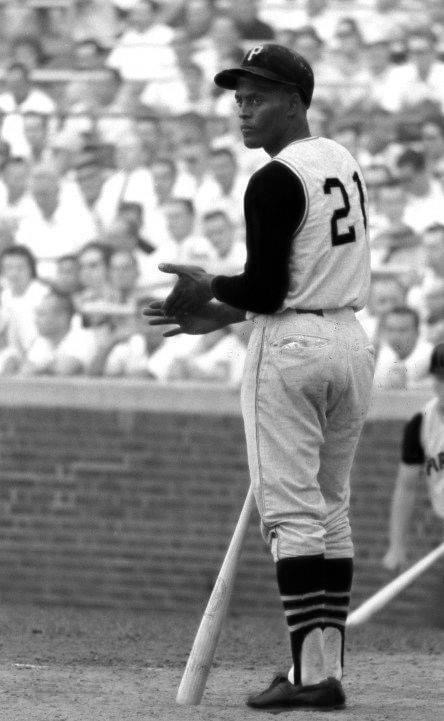

vs. Pirates (24-for-61, .393)

vs. Cubs (29-for-75, .387)

Hornsby’s personal-low mark against the Cubs would have still earned him the National League batting title.

Most Consecutive Games with an Extra-Base Hit

14 – Paul Waner, PIT NL, 6/3/1927-6/19/1927

14 – Chipper Jones, ATL NL, 6/26/2006-7/16/2006

12 – Tip O’Neill, STL AA, 8/24/1887-9/5/1887

12 – Rogers Hornsby, BOS NL, 5/27/1928(G1)-6/9/1928(G1)

11 – Rogers Hornsby, STL NL, 8/20/1924(G1)-8/27/1924

11 – Hank Greenberg, DET AL, 9/4/1940-9/14/1940

11 – Bob Bailey, MON NL, 6/22/1970(G2)-7/12/1970

11 – Jesse Barfield, TOR AL, 8/17/1985-8/27/1985

11 – Bobby Abreu, PHI NL, 5/7/2005-5/18/2005

11 – Alex Rodriguez, NY AL, 9/29/2006-4/11/2007

Quotes From Hornsby

“Hitting was my dish, not fielding. These modern hitters take their eyes off the ball. I followed the ball so closely that I could see it strike the bat.” — Hornsby, 1948

Replaced

A Chattanooga, Ohio, native named Christian Frederick Albert John Henry David Betzel (really) was the Cardinals’ starting third sacker in 1915. In 1916, Hornsby took his spot as Betzel (thankfully known as Bruno), moved to second. In 1920, Hornsby finally settled in at second base, replacing the popular Milt Stock. Finally able to relax and play at one position, Hornsby responded with his first batting title.

Replaced By

Hornsby inserted himself into the lineup as late as the age of 41 when he was a player/manager. His last full-time playing job was as the Cubs second baseman in 1931, when he hit .331 in 100 games, with 16 homers and 90 RBI. The next season, despite having the ability to be a productive everyday player, Hornsby concentrated on managing, leading the team to the NL flag, with his replacement, Billy Herman, at second.

Best Strength as a Player

Hitting the baseball.

Largest Weakness as a Player

The debate as to whether Hornsby was a good fielder, or simply average, or worse, may never be settled among baseball historians. But the statistical record shows that Hornsby posted average fielding marks and had below-average range at second base.

Other Resources & Links