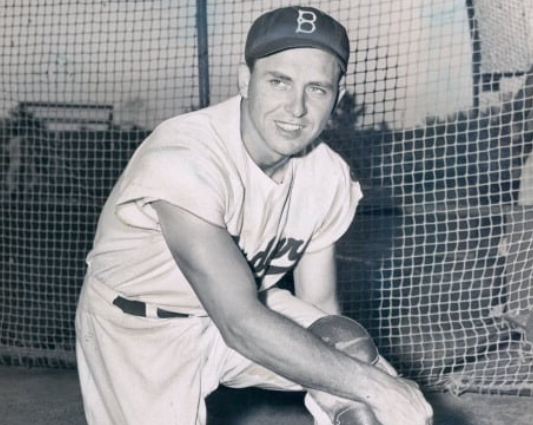

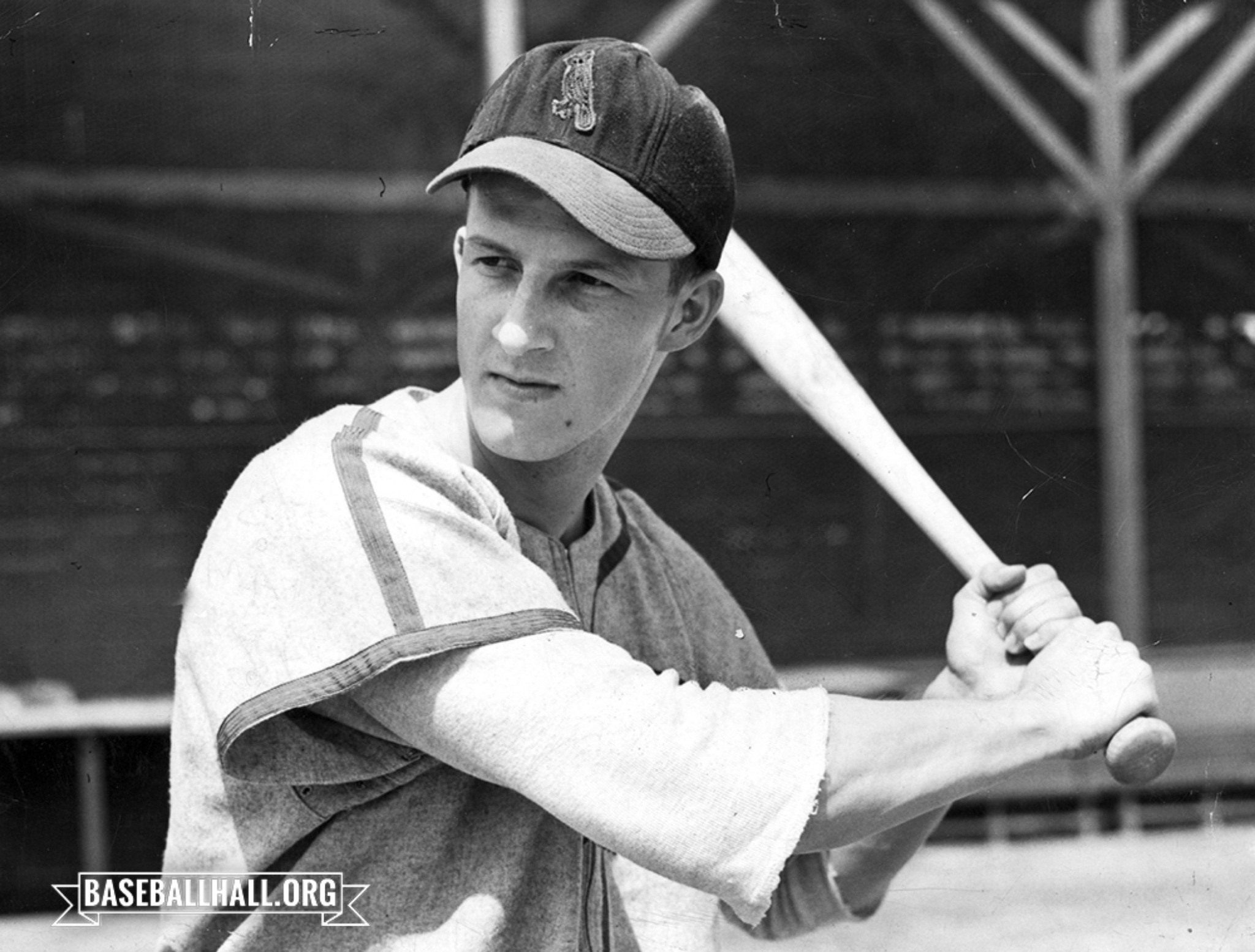

Roy Campanella

Position: Catcher

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

5-9, 190lb (175cm, 86kg)

Born: November 19, 1921 in Philadelphia, PA

Died: June 26, 1993 in Woodland Hills, CA

Buried: Cremated

High School: Simon Gratz HS (Philadelphia, PA)

Debut: April 20, 1948 (Age 26-153d, 8,045th in MLB history)

vs. NYG 0 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 29, 1957 (Age 35-314d)

vs. PHI 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1969. (Voted by BBWAA on 270/340 ballots)

View Roy Campanella’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Roy Campanella

Nicknames: Campy

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1948

Roy Campanella

Richie Ashburn

Robin Roberts

Mike Garcia

Carl Erskine

Hank Bauer

Ray Boone

Don Mueller

Satchel Paige

The Roy Campanella Teammate Team

C: Rube Walker

1B: Gil Hodges

2B: Jackie Robinson

3B: Billy Cox

SS: Pee Wee Reese

LF: Pete Reiser

CF: Duke Snider

RF: Carl Furillo

SP: Johnny Podres

SP: Sandy Koufax

SP: Carl Erskine

SP: Don Newcombe

SP: Joe Black

RP: Clem Labine

M: Chuck Dressen

Notable Events and Chronology for Roy Campanella Career

Biography

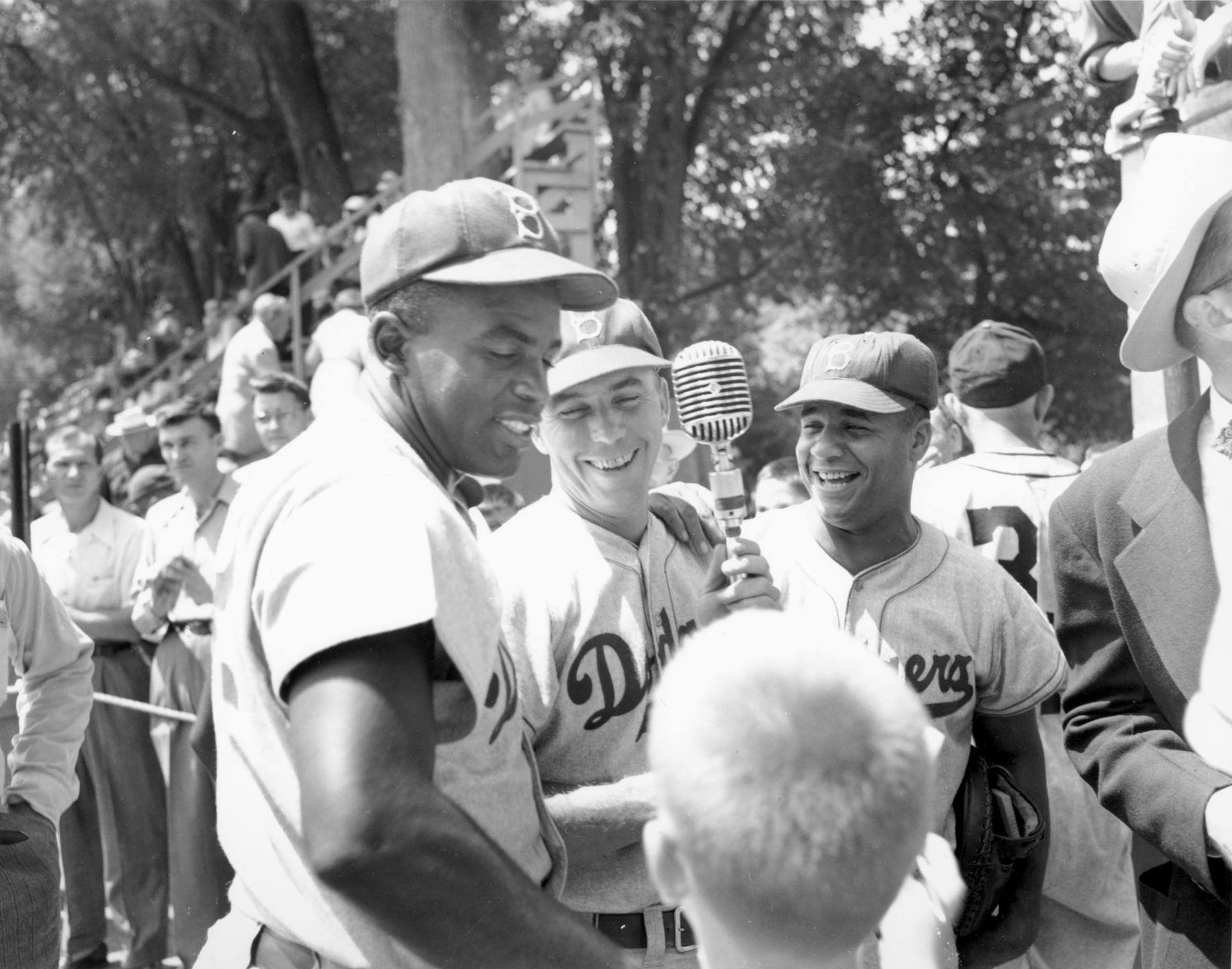

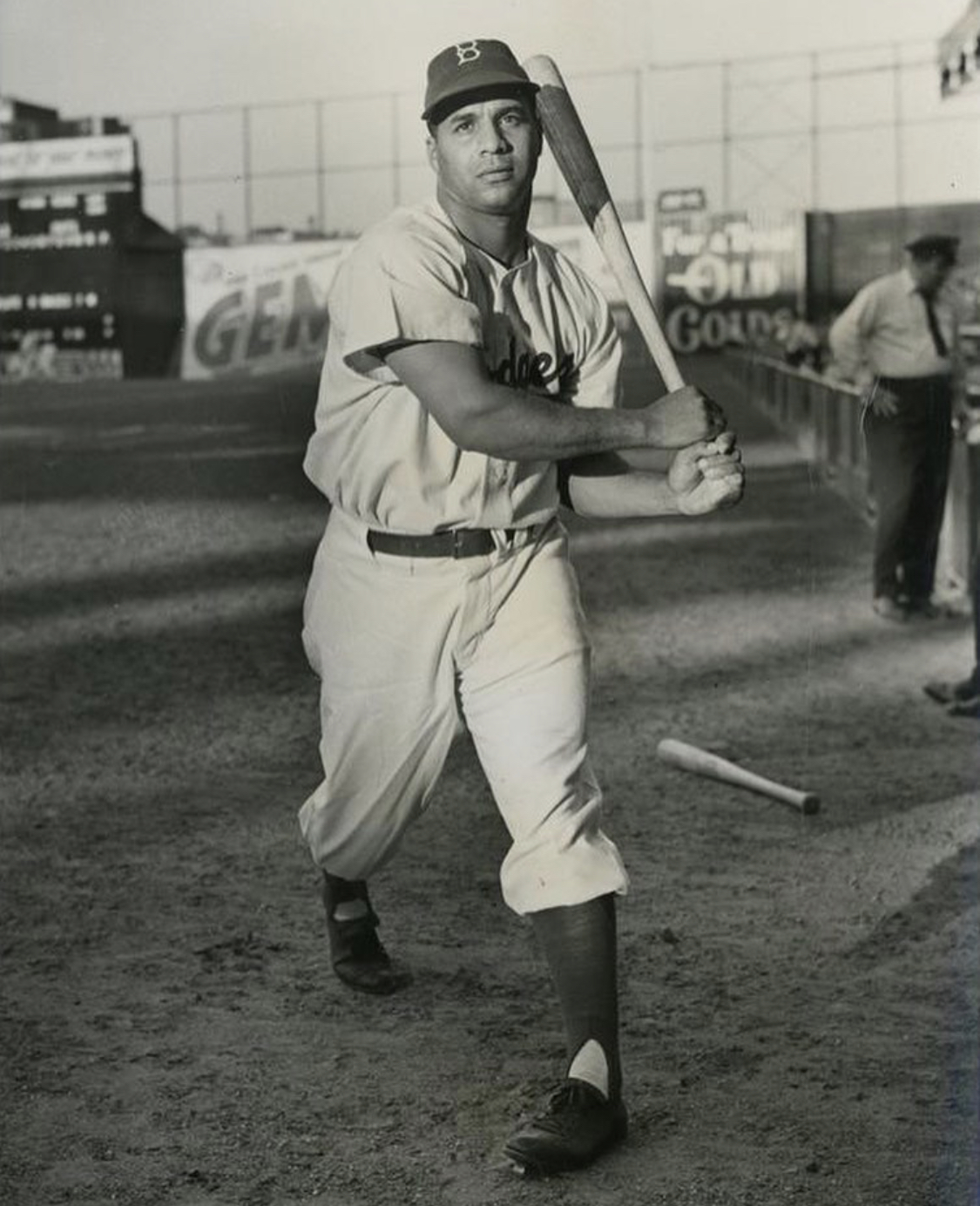

One of the greatest catchers in baseball history, Roy Campanella won three National League MostValuable Player Awards after spending his first several seasons starring in the Negro Leagues. As the cornerstone of a legendary Brooklyn Dodger team that dominated the senior circuit from 1949 to 1956, Campanella led Brooklyn to five pennants and one world championship during the eight-year period that established the Dodgers in many ways as America’s Team.

Tragically, though, Campanella’s career ended abruptly when an automobile accident left him paralyzed from the neck down. Yet, even though he never walked again, Campanella became even more of a hero to millions of Americans, providing inspiration to all he touched with his courage, perseverance, and positive outlook on life.

Roy Campanella had quite an unusual childhood for someone growing up in the United States during the 1920s and 1930s. Born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on November 19, 1921 to a black mother and an Italian father, Campanella developed a rather unique outlook on life – one that few others of segregated America undoubtedly shared. While Campanella’s mixed heritage gained him somewhat greater acceptance within the white community than most other African-Americans of his time, it nevertheless caused him to be viewed very much as a second-class citizen.

Unable to consider a career in the white major leagues a viable option during his formative years, Campanella began his baseball career at the age of 15, playing for a hometown semi-pro team, the Bacharach Giants. The teenager excelled to such a degree that the Baltimore Elite Giants of the Negro National League extended him an offer to join them early in 1937.

Still, in high school at the time, Campanella played only on weekends, substituting behind the plate occasionally for Negro League Hall of Famer Biz Mackey. After the conclusion of the season, Campanella dropped out of school on his 16th birthday to play for the team full-time. He followed the Elite Giants when they moved to Baltimore in 1938, earning the team’s starting catching job the following year. Campanella subsequently went on to establish himself as one of the Negro Leagues’ finest players, eventually challenging the aging Josh Gibson for supremacy among all league receivers.

The 19-year-old Campanella earned MVP honors at the 1941 East-West All-Star game, but jumped to the Mexican League the following year after quarreling with Baltimore owner Tom Wilson. He spent the next two years playing south of the border, before rejoining the Giants in 1944. After starring for the Giants in both 1944 and 1945, Campanella became one of five black players who signed with Brooklyn general manager Branch Rickey to join the Dodger organization in 1946.

Campanella spent the next two years in the minor leagues, patiently awaiting his promotion to the Dodgers, while Jackie Robinson paved the way for him and other talented young black players at the major-league level.

Campanella earned a spot on the Brooklyn roster in spring training of 1948 and made his debut with the team at the age of 26 on April 20th. However, he struggled early in the year, allowing Branch Rickey to fulfill his desire to integrate the American Association by sending the catcher to St. Paul for a brief stint. After Campanella righted himself, he was quickly recalled, spending the remainder of the season with the Dodgers, for whom he batted .258, hit nine home runs, and knocked in 45 runs in 83 games.

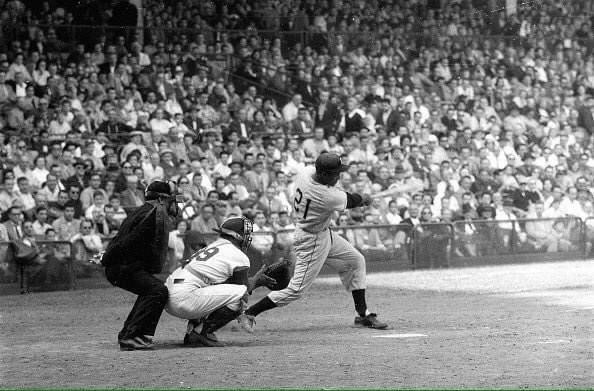

Campanella began to establish himself as the National League’s premier catcher the following year, finishing the 1949 campaign with 22 home runs, 82 runs batted in, and a .287 batting average. His solid performance earned him the first of eight consecutive appearances on the All-Star team and helped lead the Dodgers to the National League pennant. Brooklyn fell just short of winning the league championship again in 1950, but Campanella posted even better numbers, hitting 31 homers, driving in 89 runs, and batting .281.

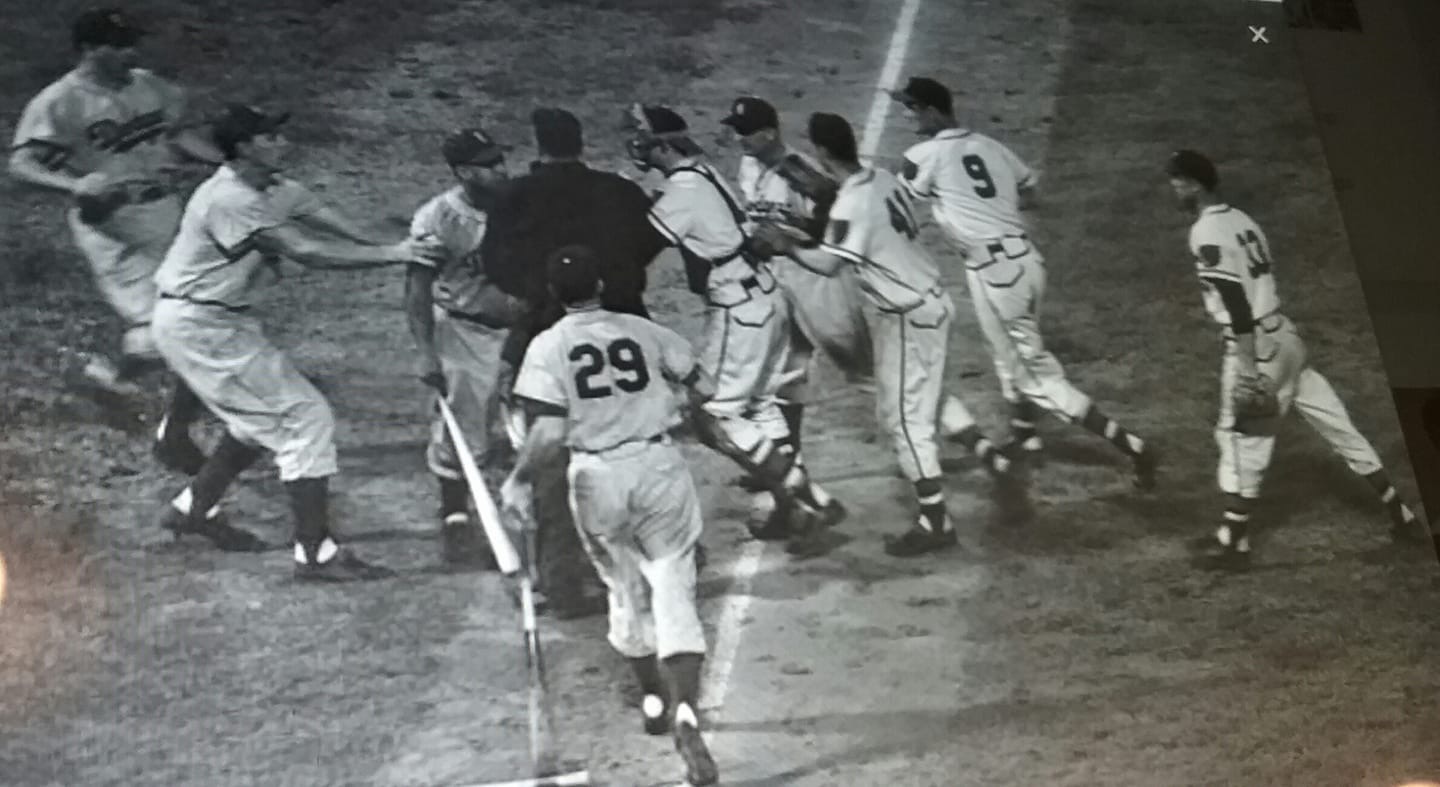

The Brooklyn receiver had his first dominant season in 1951, placing among the league leaders with 33 home runs, 108 runs batted in, a .325 batting average, 33 doubles, a .393 on-base percentage, and a .590 slugging percentage, en route to capturing N.L. MVP honors. The Dodgers came up a bit short again that year, losing a three-game playoff series to the hated New York Giants on Bobby Thomson’s pennant-clinching three-run homer in the bottom of the ninth inning in Game Three.

However, they won the league championship in each of the next two seasons, with Campanella being a key contributor both times. After hitting 22 home runs and knocking in 97 runs in 1952, the Dodger catcher had his greatest season the following year. Campanella won his second MVP Award in three seasons, batting .312 and establishing career highs with 41 homers, 103 runs scored, a .395 on-base percentage, a .611 slugging percentage, and a league-leading 142 runs batted in. His 40 home runs as a catcher that year remained the major league record for receivers until 1996, when Todd Hundley hit 42 homers for the Mets. Campanella’s 142 RBIs are also the second-highest single-season total in club history (Tommy Davis knocked in 153 runs in 1962).

A damaged nerve caused by a chipped bone in the heel of his left hand limited Campanella to just 111 games in 1954, and greatly reduced his effectiveness. The All-Star receiver ended the campaign with only 19 home runs, 51 runs batted in, and an anemic .207 batting average. He bounced back the following year, though, to capture his third N.L. MVP Award by hitting 32 homers, driving in 107 runs, and batting .318. He then hit two home runs and knocked in four runs against the Yankees in the World Series, as the Dodgers won their only world championship in Brooklyn.

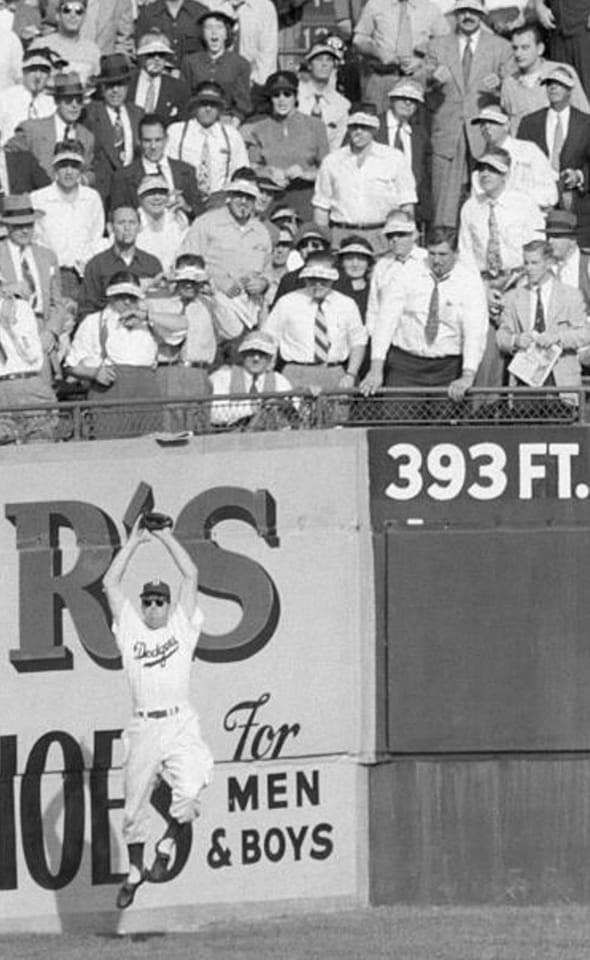

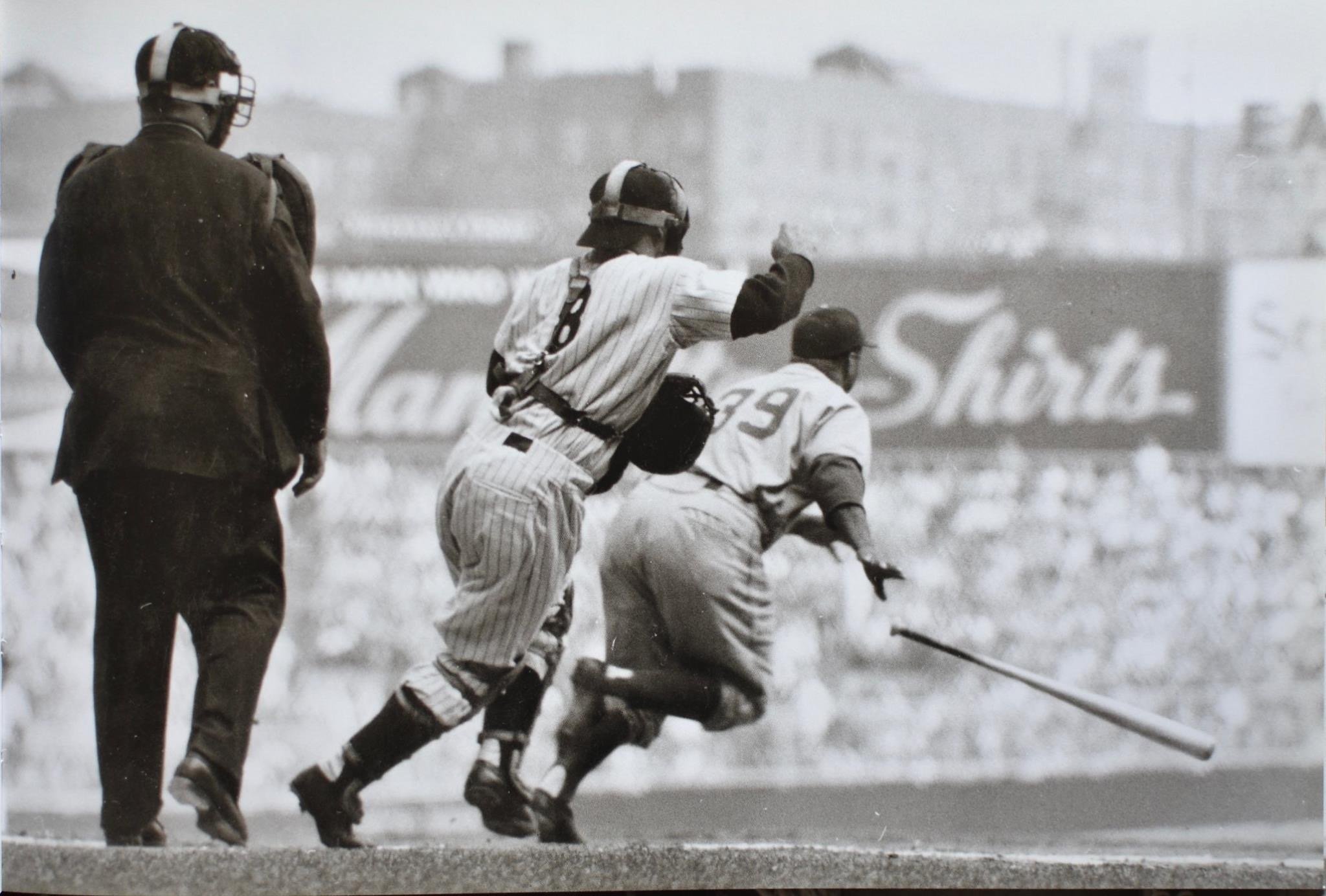

Campanella’s potent bat certainly made him an integral part of the success Brooklyn’s Boys of Summer experienced between 1949 and 1956. Making his value even more inestimable were his calm demeanor, exceptional defensive skills, and outstanding ability to handle a pitching staff. An extremely intelligent player, Campanella never seemed flustered, and he was a superb signal-caller. As the major leagues’ first black catcher, Campanella did an excellent job of handling a predominantly white pitching staff. He also possessed unusual mobility, quickness, and grace for a man of his proportions, since the Dodger receiver’s 5’9″, 195-pound frame gave him a somewhat stocky appearance. Blessed with an outstanding arm, Campanella threw out 57% of the baserunners who attempted to steal a base against him over the course of his career. That percentage is the highest by any catcher in major league history.

A recurrence of Campanella’s earlier hand injury led to a disappointing 1956 campaign in which the receiver batted just .219 and scored only 39 runs. Injuries continued to plague the 35-year-old catcher the following year, limiting him to only 103 games, 13 home runs, 62 runs batted in, and a .242 batting average. However, as Campanella mended during the off-season, he anticipated a bounce-back year in 1958, even though he and the rest of the Dodgers regretted leaving the friendly confines of Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field for the Los Angeles Coliseum. Campanella failed to play a single game in the Dodgers’ new home, though, as his career, and nearly his life, came to a sudden end on a cold wintery night.

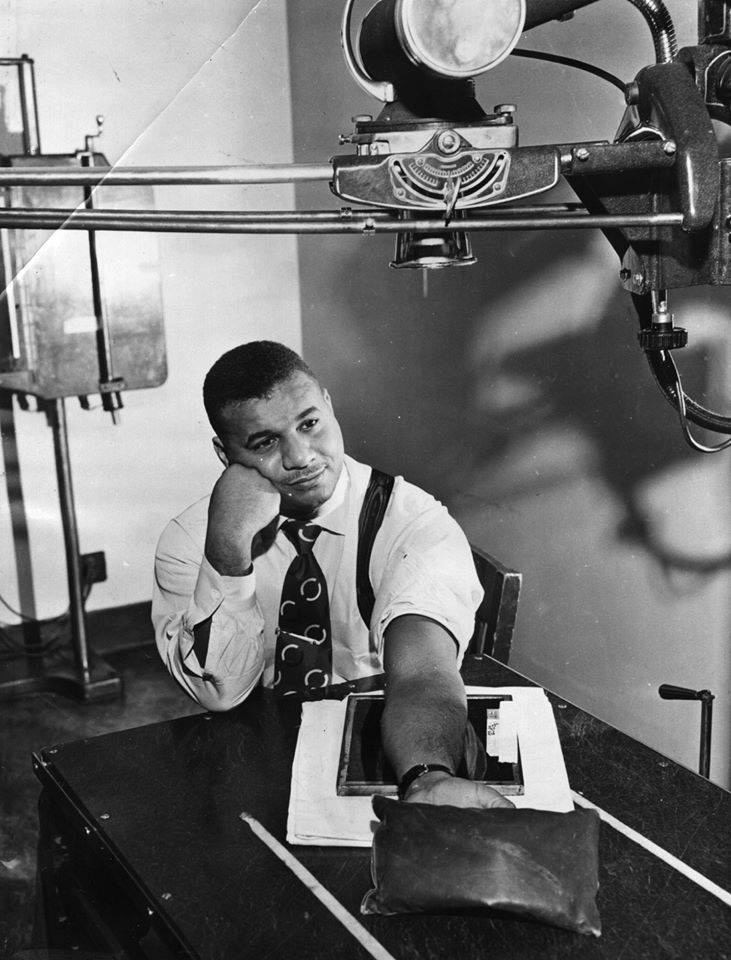

On January 28, 1958, after doing a double-shift at the liquor store he owned in Harlem, Campanella began the long drive back to his home on Long Island. With his car traveling approximately 30 mph, Campanella lost control of his vehicle when it hit a patch of ice. Skidding along the road’s slick surface, the car crashed into a telephone pole and flipped over onto its side, pinning Campanella behind the steering wheel and breaking his neck. The accident fractured Campanella’s fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae, and compressed his spinal cord, leaving him paralyzed from the shoulders down.

A little over 15 months later, on May 7, 1959, the Dodgers honored Campanella with Roy Campanella Night at the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum. The New York Yankees agreed to make a special trip to Los Angeles to play the Dodgers in an exhibition game, the proceeds of which were used to defray the cost of Campanella’s medical bills. The fans in attendance numbered 93,103, setting a record at the time for the largest crowd ever to attend a Major League Baseball game. The most chilling moment of the evening’s festivities took place when the stadium’s lights dimmed for several moments, with everyone in the record crowd subsequently paying tribute to the former Dodger great by lighting a match.

Campanella spent the remainder of his life confined to a wheelchair, with only limited use of his arms as well. Yet, after initially suffering through a period of deep depression, he eventually resigned himself to his condition, endured years of physical therapy, and eventually regained substantial use of his arms and hands. He was able to feed himself, shake hands, and gesture while speaking. Although he never walked again, Campanella became an inspiration for millions of Americans, giving motivational speeches to youngsters around the nation. Campanella lived far beyond the normal span for quadriplegics, surviving long after being elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame by the members of the BBWAA in 1969. He eventually died of a heart attack on June 26, 1993, in his Woodland Hills, California home at the age of 71.

Upon learning of Campanella’s passing, Tommy Lasorda said, “Now he won’t be suffering anymore. I loved Roy Campanella, I loved him like a brother. I’m going to miss him very much. As well as being a great baseball player, he was a great human being.”

The quality of Roy Campanella’s character is perhaps best exemplified by the following words he spoke during one of the many motivational speeches he delivered through the years:

“I asked God for strength, that I might achieve. I was made weak, that I might learn humbly to obey. I asked for health, that I might do great things. I was given infirmity, that I might do better things. I asked for riches, that I might be happy. I was given poverty, that I might be wise. I asked for power, that I might have the praise of men. I was given weakness, that I might feel the need of God. I asked for all things, that I might enjoy life. I was given life, that I might enjoy all things… I got nothing I asked for but everything I hoped for. Almost despite myself, my unspoken prayers were answered. I am, among men, most richly blessed!”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Brooklyn Dodgers (1948-1957)

Similar: Ivan Rodriguez

Linked: Yogi Berra, Johnny Bench, Jackie Robinson

Best Season, 1953

Winning his second MVP Award, Campanella set career-highs in games, at-bats, runs (103), homers (41), RBI (142), walks (67), and slugging (.611). Like many catchers, he was an inconsistent performer offensively, having a terrible season in 1954, before bouncing back again in 1955 for his final MVP Award.

Awards and Honors

1951 NL MVP

1953 NL MVP

1955 NL MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1949 World Series

1952 World Series

1953 World Series

1955 World Series

1956 World Series

Factoid

For five years, from 1949 through 1953, Roy Campanella caught every inning of every All-Star game for the National League.

Where He Played: Catcher, exclusively (1,183 games). However, Campanella caught as many as 140 games in just two seasons.

Notes

Campy hit safely in each of the Dodgers’ first seven games in 1952, hitting .443 (13-for-30). Despite the hot start, he hit just .258 the remainder of the season, slumping 56 points below his average from the previous year.

Injuries and Explanation for Missed Playing Time

Campanella chipped a bone in his left hand during spring training in 1954 causing nerve damage that was tough to overcome. He batted only .207 for the year. But the following year he made an incredible comeback – winning a third MVP award. He batted .318 with 32 home runs and 107 runs batted in. Yet in ’56 Campy was at it again – struggling in an even-numbered year. The pattern actually could be traced back to the 1952 season, when he batted just .269 while battling nagging injuries. Campy’s curious record in even years: .248, .447 SLG, 20 home runs, 71 RBI. In odd-years, he averaged .301, .546 SLG, 28 homers, and 100 RBI.

Transactions

In a dispute with Elite Giants owner Tom Wilson which resulted in a $250 fine that he refused to pay, Campanella made a jump to the Mexican League in 1942. In 1942 and 1943 he made just $100 a month plus expenses playing for the Mexican Monterey team. Campanella returned to the Negro leagues for the 1944 season after Wilson dropped the fine he had previously imposed. Campanella’s salary was raised to $3,000 a year and he received a $300 signing bonus.

Good To Be Alive

In 1959 the Yankees and Dodgers held an exhibition game in Campanella’s honor at Los Angeles Coliseum. The crowd of 93,103 remains a baseball record. The emotional Campanella addressed the crowd from his wheelchair, stating: “I thank God that I’m living to be here. I thank every one of you from the bottom of my heart.” After concluding his remarks, the lights went out and everyone in attendance lit a match to honor his courage.

Factoid

Roy Campanella was the first black man to manage a game in a white minor league.

Factoid

In 1946, Walter Alston, manager of the Nashua Dodgers, was ejected from a game. As he left the field he told Roy Campanella to take over. Thus, Campanella became the first african-american to manage (though unofficially) a regular season game in organized white baseball.

All-Star Selections

1949 NL

1950 NL

1951 NL

1952 NL

1953 NL

1954 NL

1955 NL

1956 NL

Replaced

Campanella beat out Bruce Edwards, who had a very good season as a 23-year old in 1947, hitting .295 with nine homers and 80 RBI. But Campanella’s power and defensive ability were superior, and Edwards served as Campy’s caddy until 1951, when he was traded to the Cubs.

Replaced By

Johnny “Rosie” Roseboro, a rookie catcher in 1957, who assumed the starting job in 1958 after Camp was paralyzed in his car accident. Roseboro remained the Dodger starting catcher for a decade, contributing to four pennant-winners.

Best Strength as a Player

Power

Largest Weakness as a Player

Running speed

Other Resources & Links