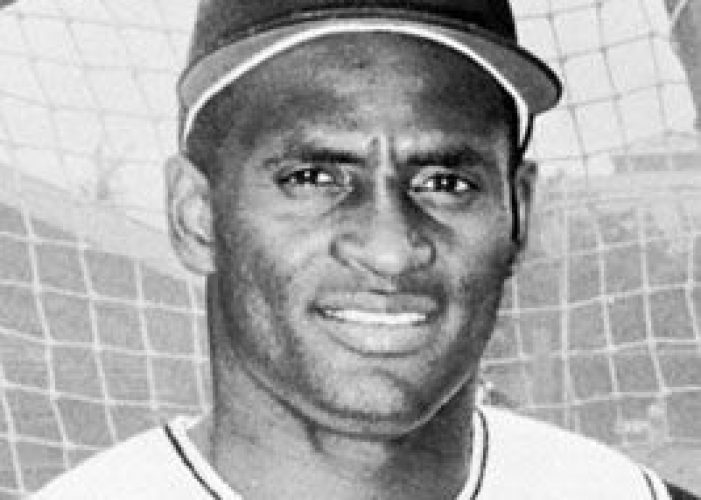

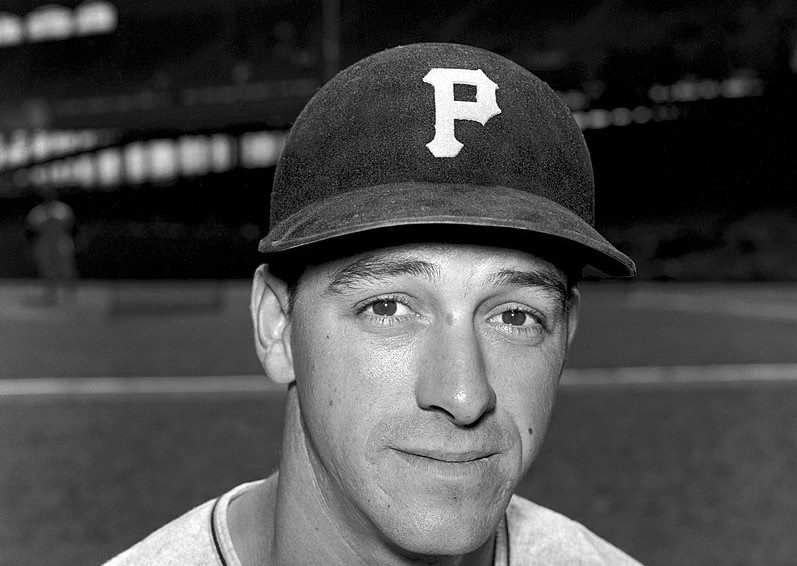

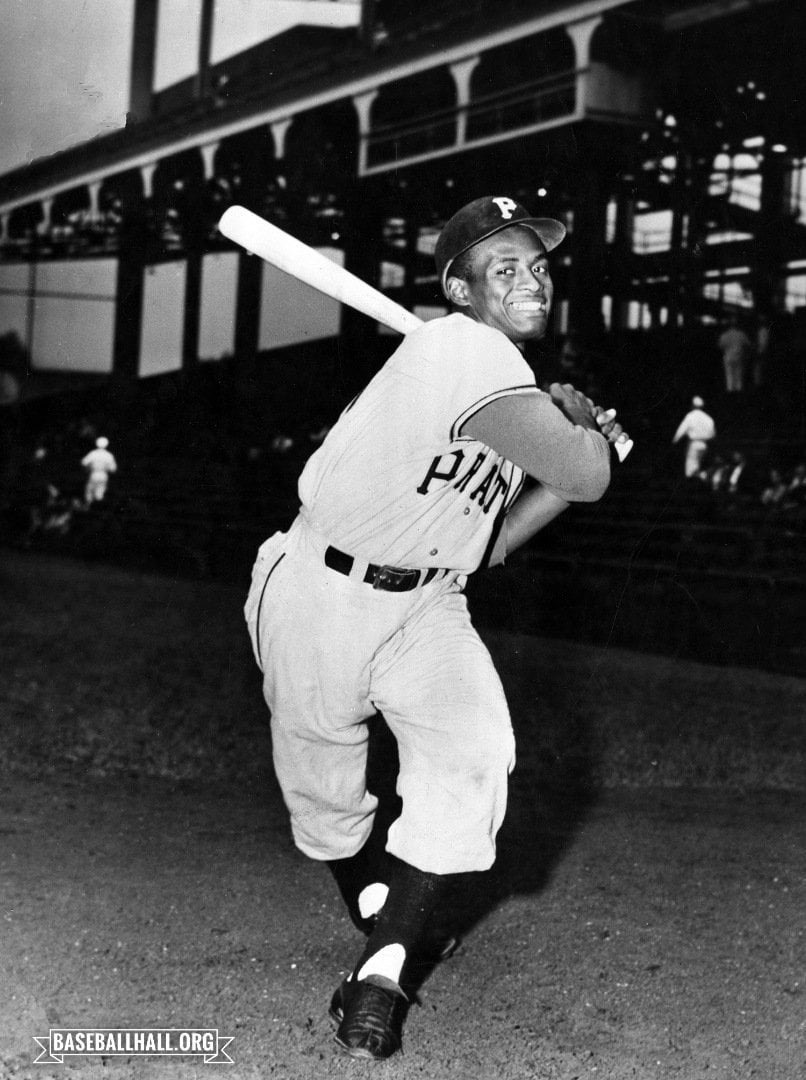

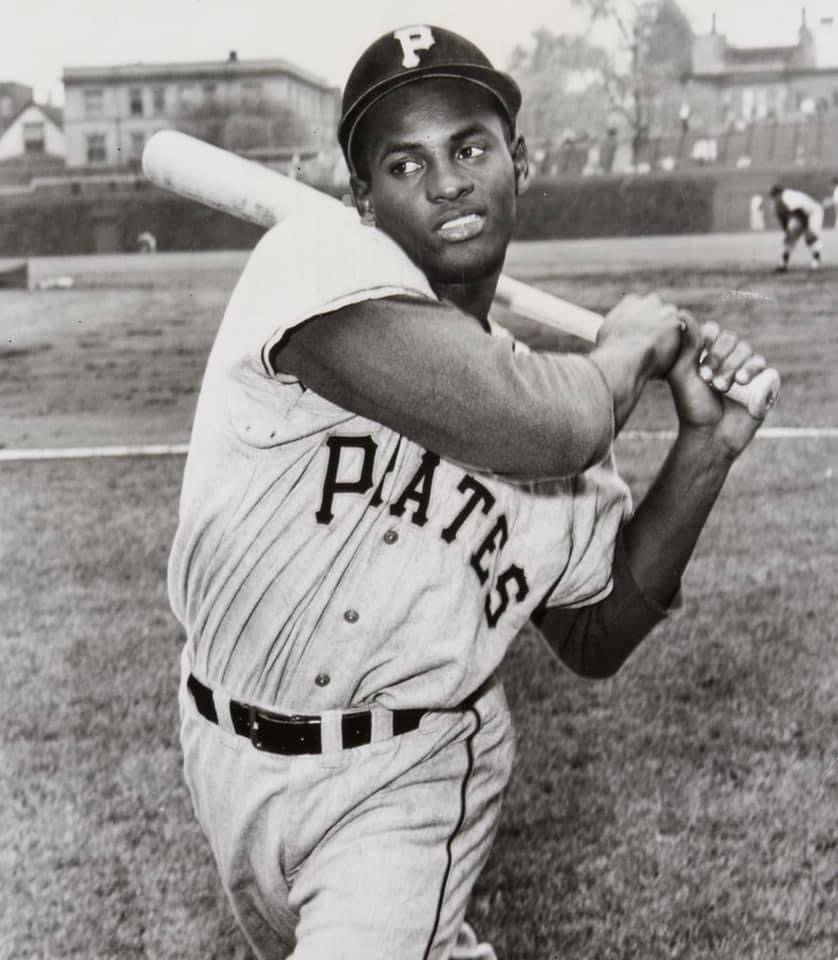

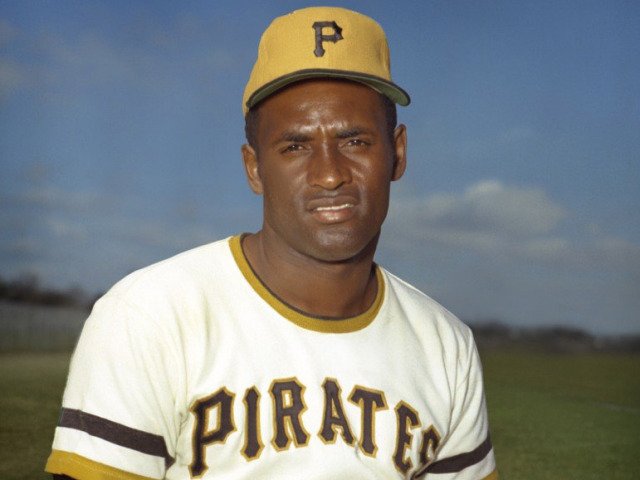

Roberto Clemente

Position: Rightfielder

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

5-11, 175lb (180cm, 79kg)

Born: August 18, 1934 in Carolina, Puerto Rico pr

Died: December 31, 1972 in San Juan, Puerto Rico

Buried: Died at Sea

High School: Julio C. Vizarrondo (Carolina, Puerto Rico)

Debut: April 17, 1955 (11,239th in major league history)

vs. BRO 4 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: October 3, 1972

vs. STL 0 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1973. (Voted by Special Election)

View Roberto Clemente’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Roberto Clemente

Nicknames: Arriba or The Great One

Relatives: Uncle of Edgard Clemente

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1955

Brooks Robinson

Roberto Clemente

Ken Boyer

Rocky Colavito

Clete Boyer

Elston Howard

Sandy Koufax

Jim Bunning

Bill Virdon

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology for Roberto Clemente Career

Biography Roberto Clemente

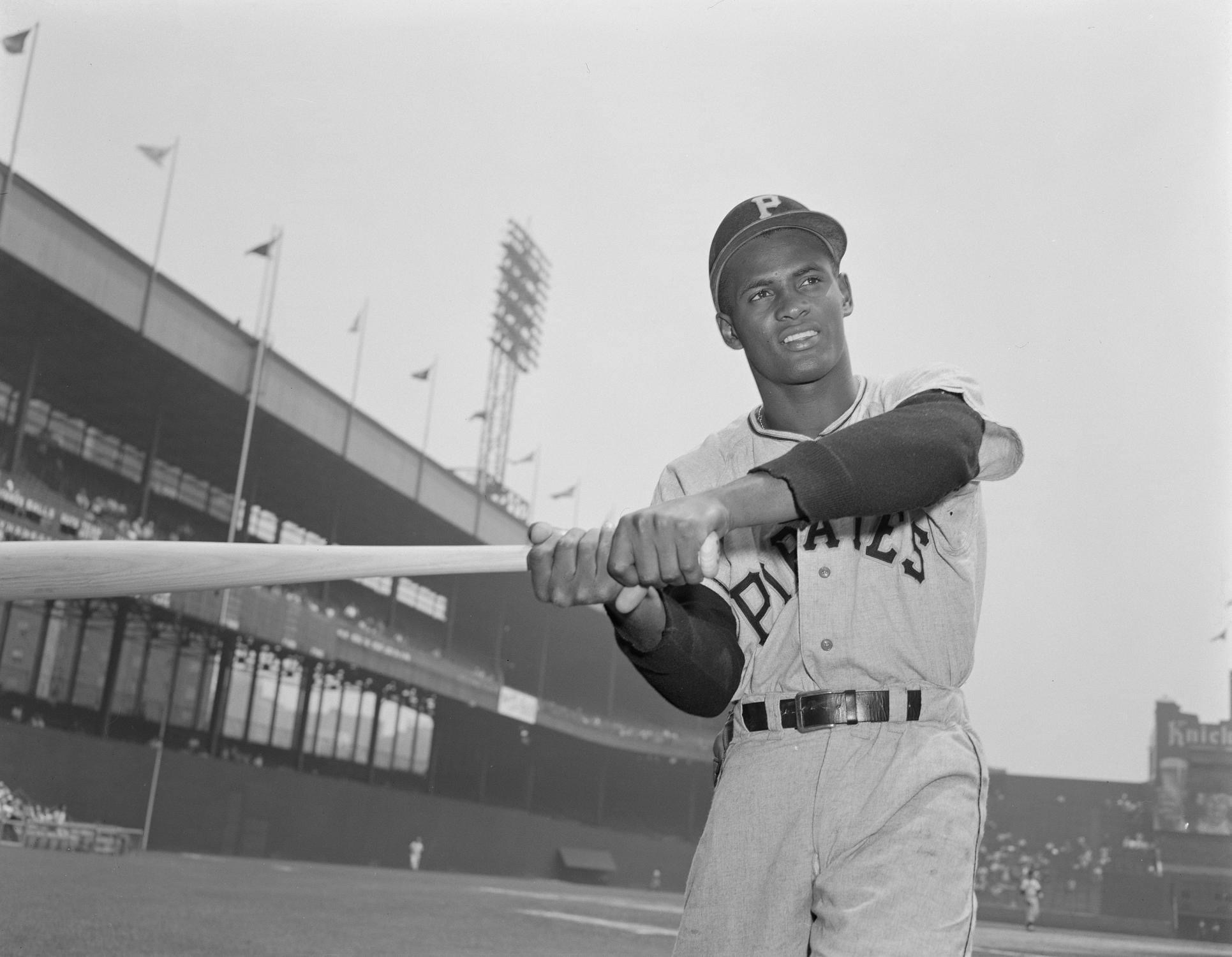

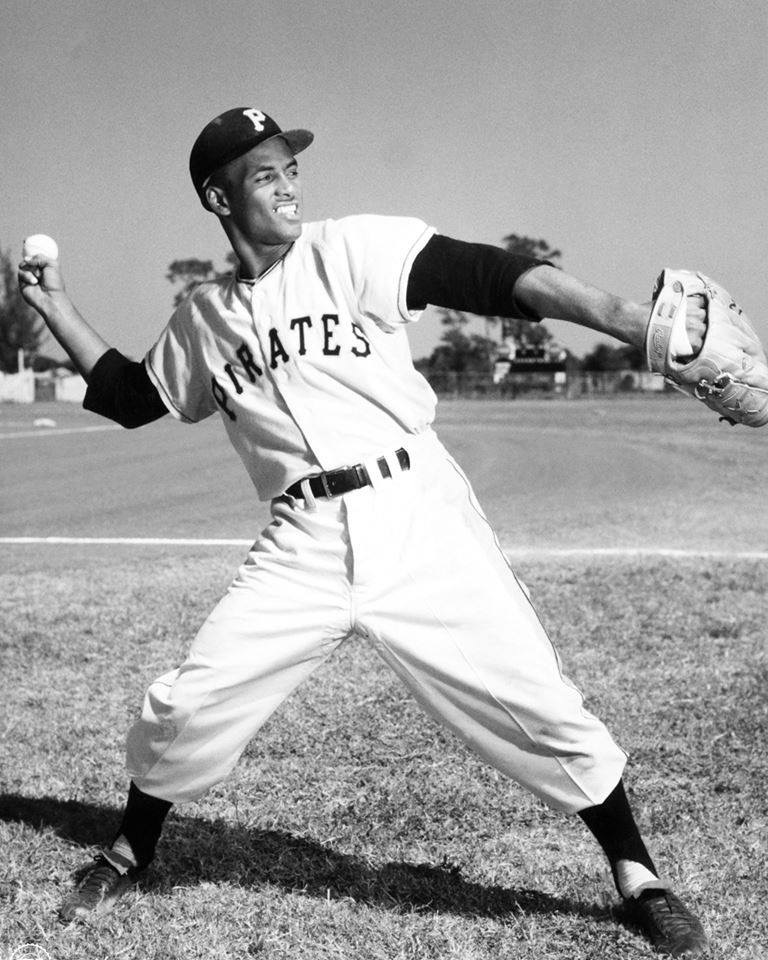

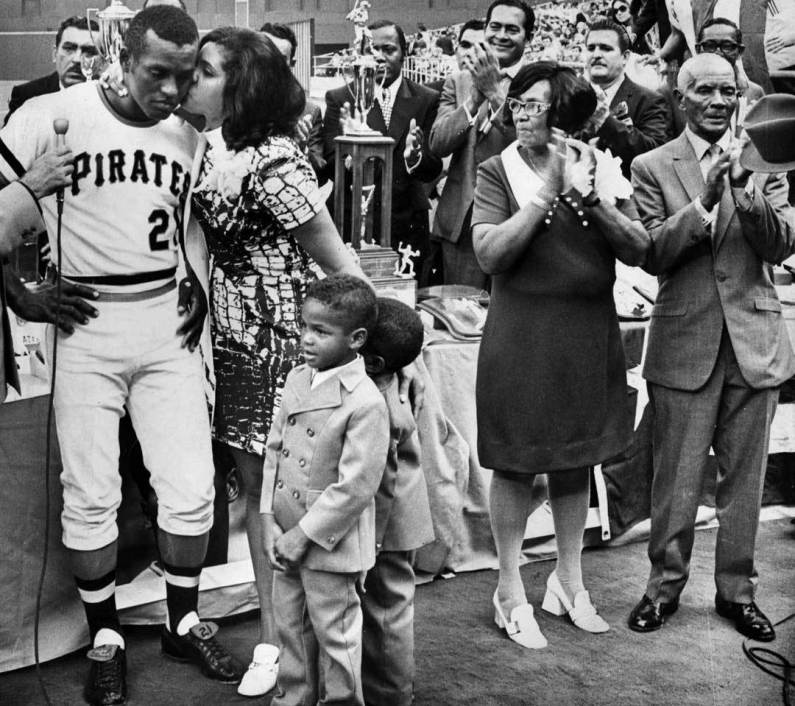

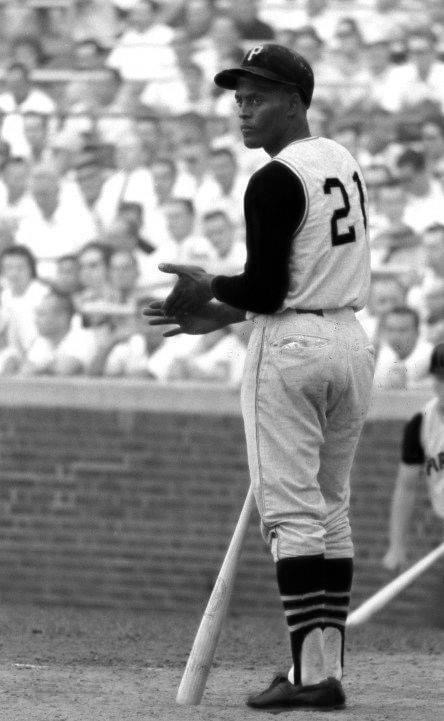

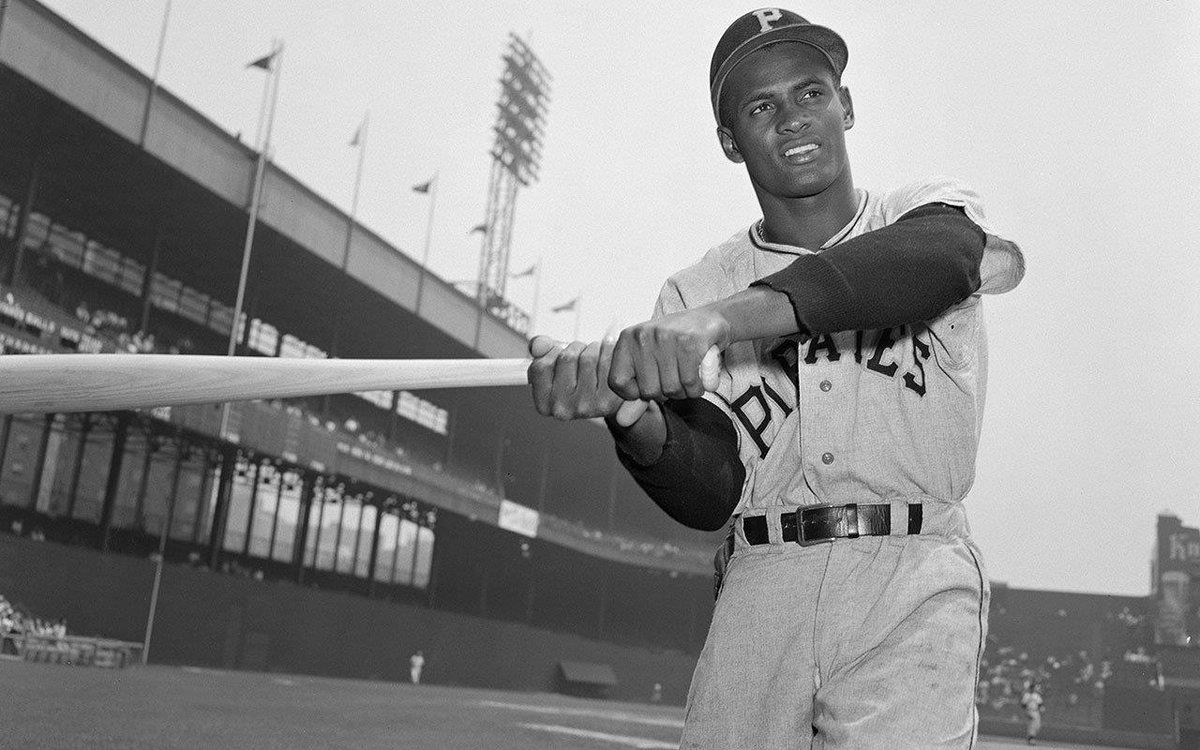

As the first truly great player of Latin-American heritage to don a major league uniform, Roberto Clemente paved the way for other young Hispanic men to pursue a playing career in the United States. He did so by not only excelling in every aspect of the game throughout his brilliant 18-year career but also by carrying himself with a graceful elegance that enabled him to eventually raise the social consciousness of an entire city.

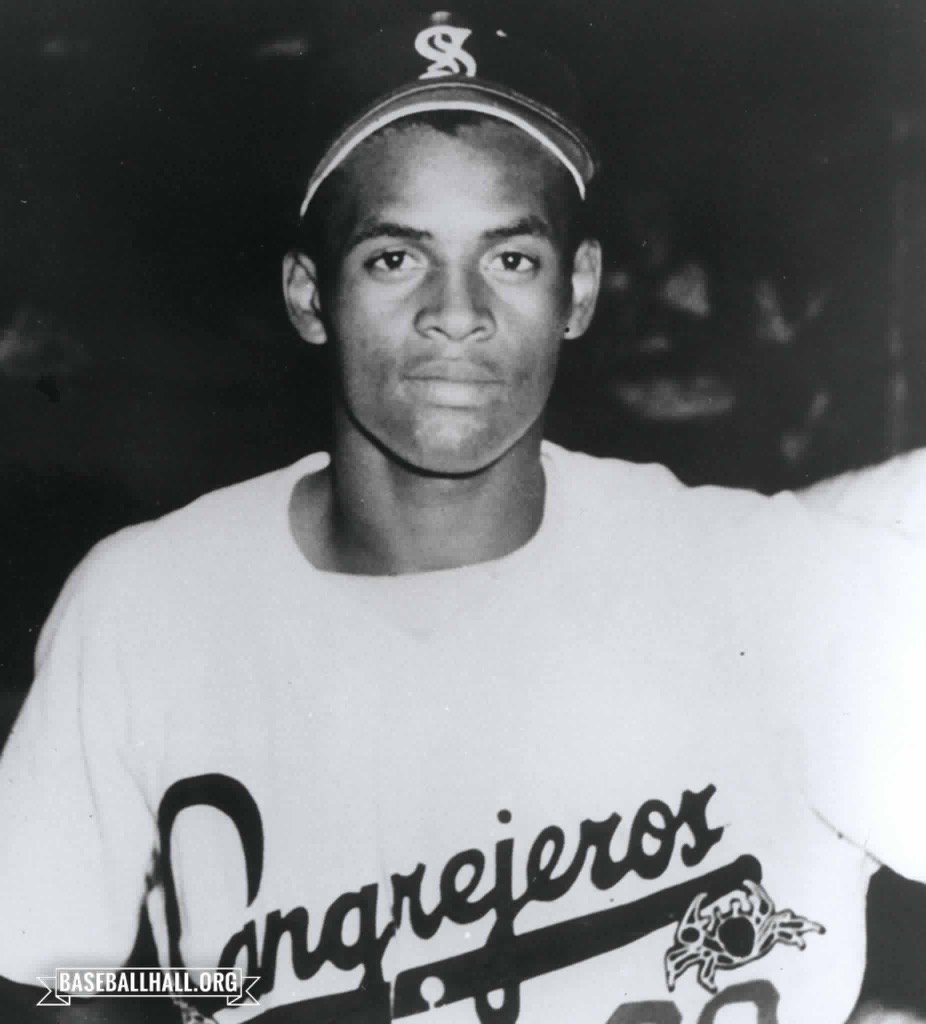

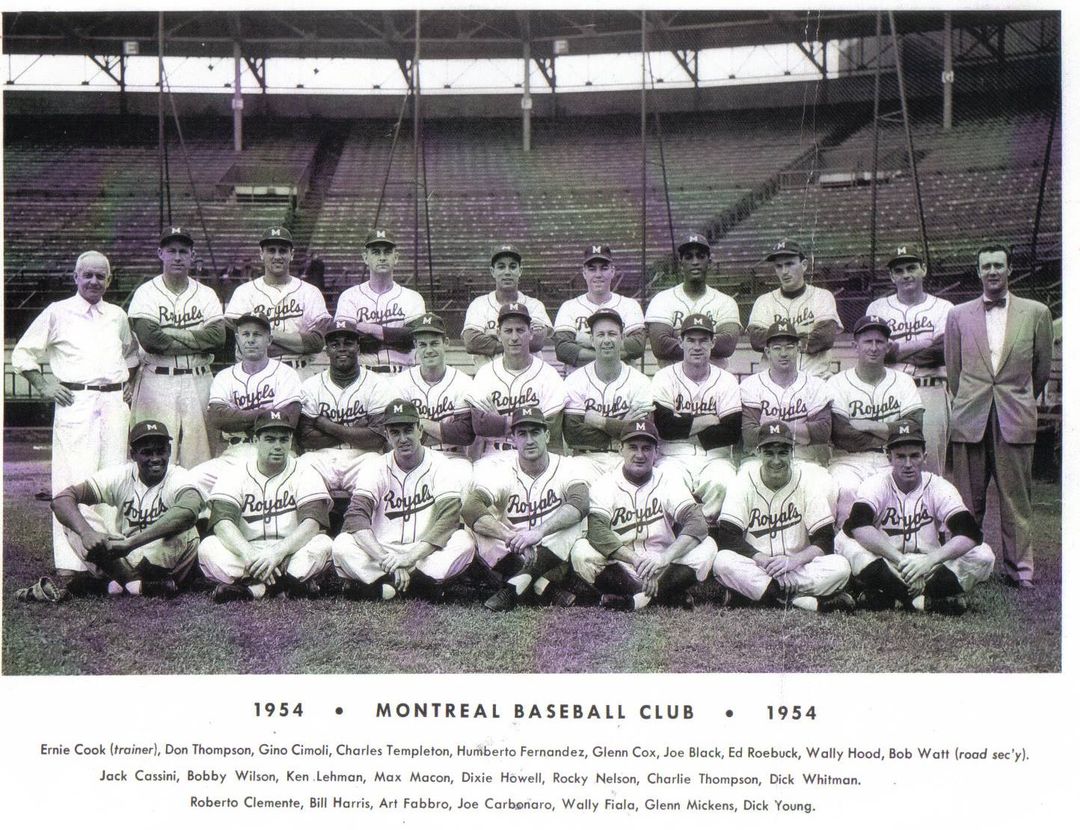

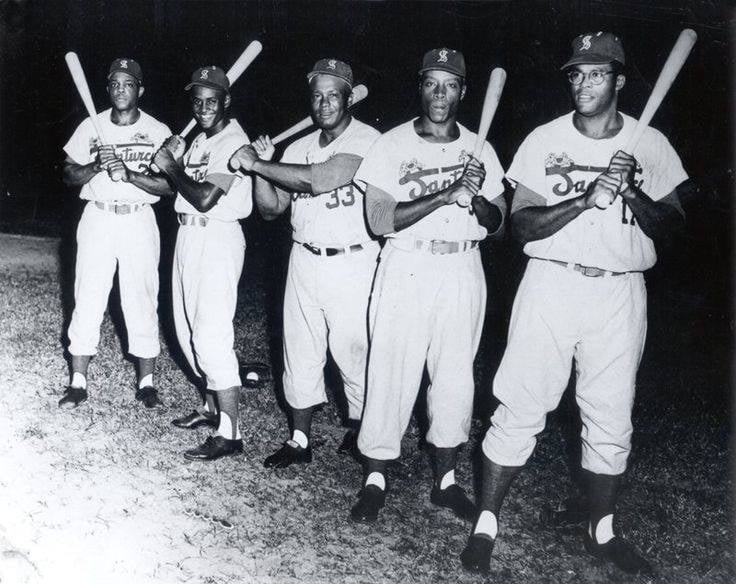

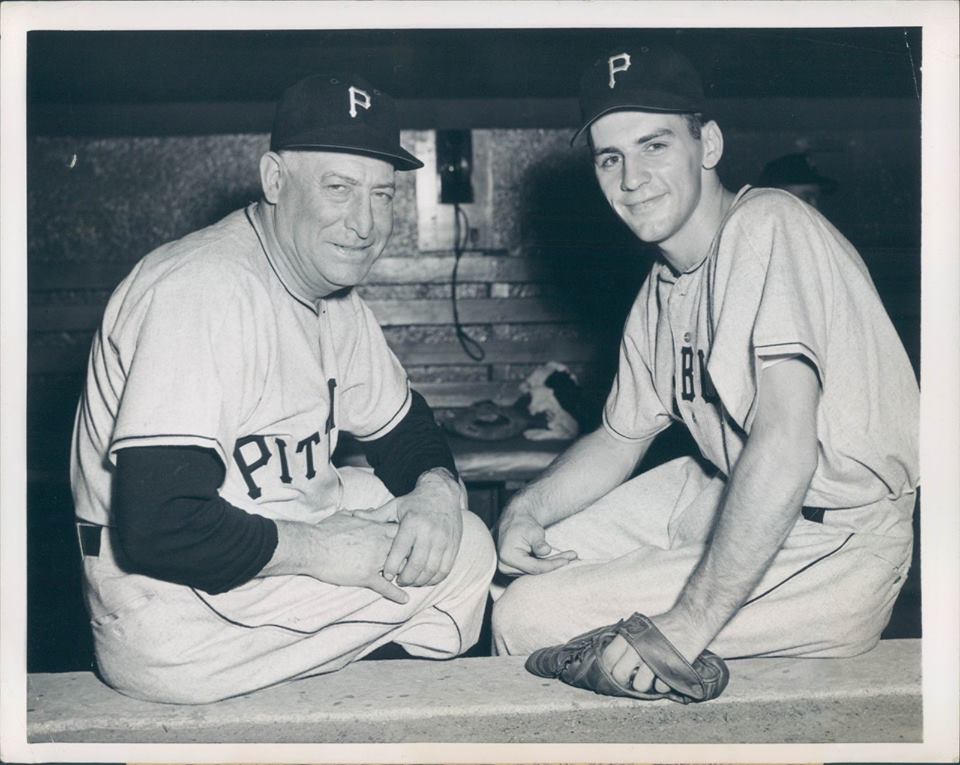

Born in Carolina, Puerto Rico, the youngest of seven children, on August 18, 1934, Roberto Clemente Walker faced numerous obstacles during the early stages of his major league career, which began with the Pittsburgh Pirates some 20 years later. Clemente’s professional playing career actually began with the Santurce Crabbers in the Puerto Rican Professional Baseball League. A Brooklyn Dodger scout offered Clemente a contract after watching him play for Santurce, and the outfielder subsequently joined Brooklyn’s Triple-A affiliate, the Montreal Royals. He remained with the Royals until he was drafted by the Pirates in the Major League Baseball draft that took place on November 22, 1954.

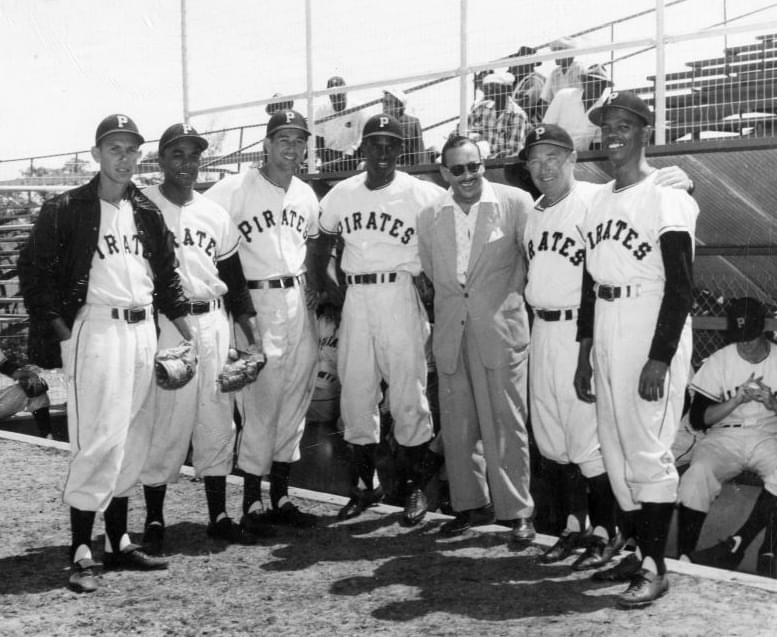

Clemente experienced a great deal of frustration his first few years in Pittsburgh, after first joining the team as a 20-year-old in 1955. While dark-skinned players always had a difficult time being accepted into the world of white baseball throughout the period immediately following the breaking of the color barrier, things were particularly hard on Clemente. Not only did he have to deal with the prejudices that were bound to come his way because of the color of his skin, but he also had to learn a new culture and a new language. However, neither the members of the media nor most of Clemente’s own teammates made his transition an easy one. The newspaper columnists and broadcasters of the day seemed unwilling to fully accept his Latin heritage. Clemente’s speech was openly mocked by the writers in their newspaper articles, and broadcasters attempted to Americanize his name by referring to him as either “Bob” or “Bobby”, instead of “Roberto”, which was the name he wished to be called by. Even most of Clemente’s teammates, with whom the rightfielder rarely socialized, failed to call him by his proper name. Roberto responded to any racial tensions that existed between himself, the media, and his teammates by stating, “I don’t believe in color.” He noted that, during his upbringing, he was taught to never discriminate against anyone based on their ethnicity.

Further alienating Clemente to both the media and his teammates was the general perception they held towards him that he was a hypochondriac who lacked proper motivation. Constantly complaining of aches and pains, Roberto typically missed a significant number of games each season due to the various physical ailments that plagued him. Not generally known, though, was the fact that much of Clemente’s discomfort stemmed from a partially damaged spinal column he suffered from as the result of a serious car accident he was involved in midway through his rookie season.

Clemente’s injuries cut into his playing time significantly his first few seasons, limiting him to fewer than 125 games in three of his first five years in Pittsburgh. His offensive productivity was further curtailed by the many cultural problems he faced during his period of adjustment. As a result, Clemente failed to hit more than 7 home runs, drive in more than 60 runs, or score more than 69 runs in any of his first five seasons. He also batted over .300 just once, compiling an average of .311 in 1956.

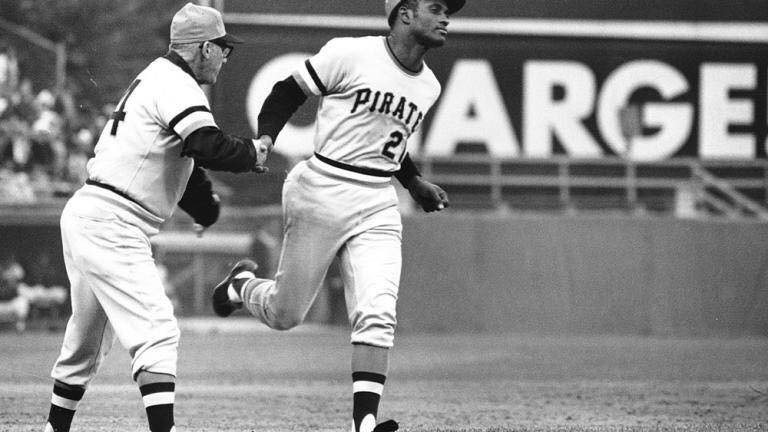

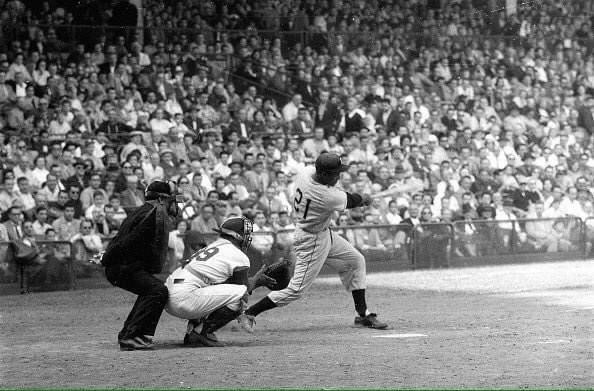

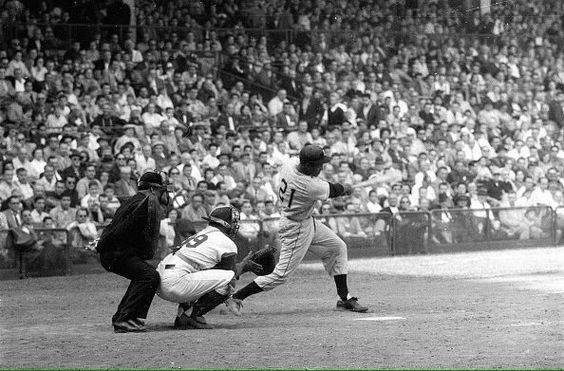

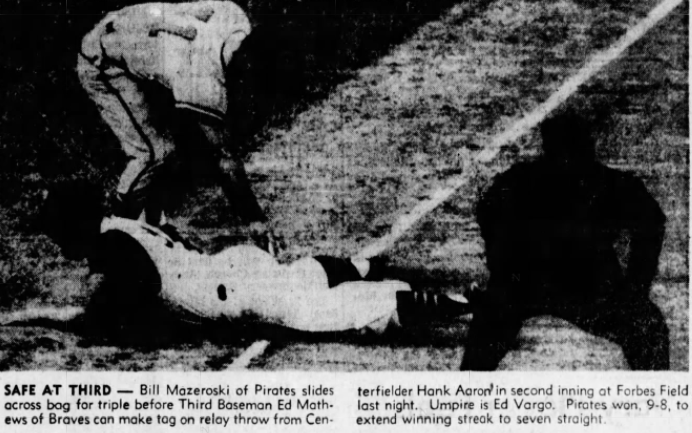

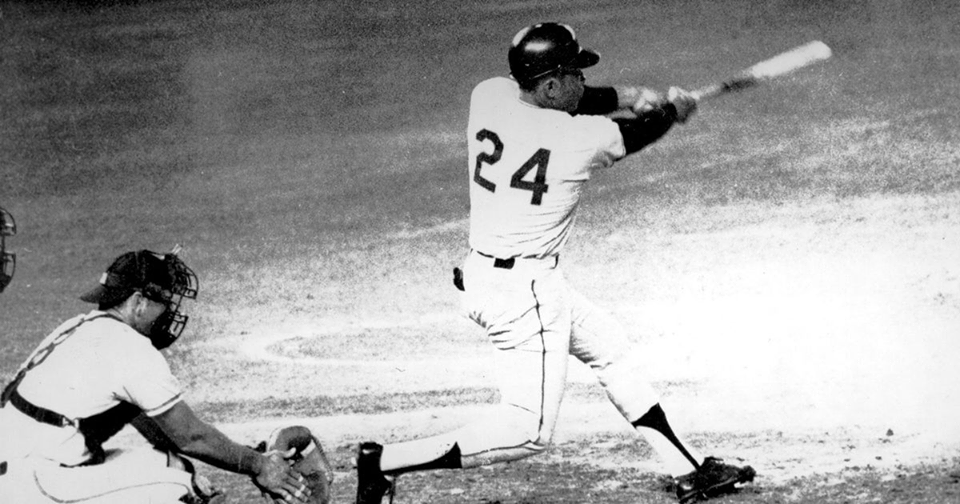

Clemente had his breakout year in 1960, helping the Pirates win the National League pennant by hitting 16 homers, knocking in 94 runs, scoring 89 others, batting .314, and appearing in his first All-Star Game. The rightfielder then hit successfully in all seven World Series games, as the Pirates upset the heavily-favored Yankees despite being outscored by a total margin of 55-27 during the Fall Classic. Clemented finished eighth in the league MVP voting at season’s end.

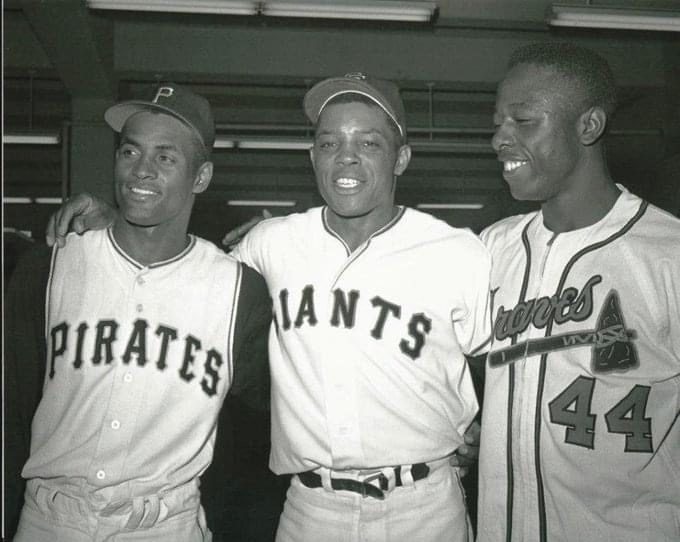

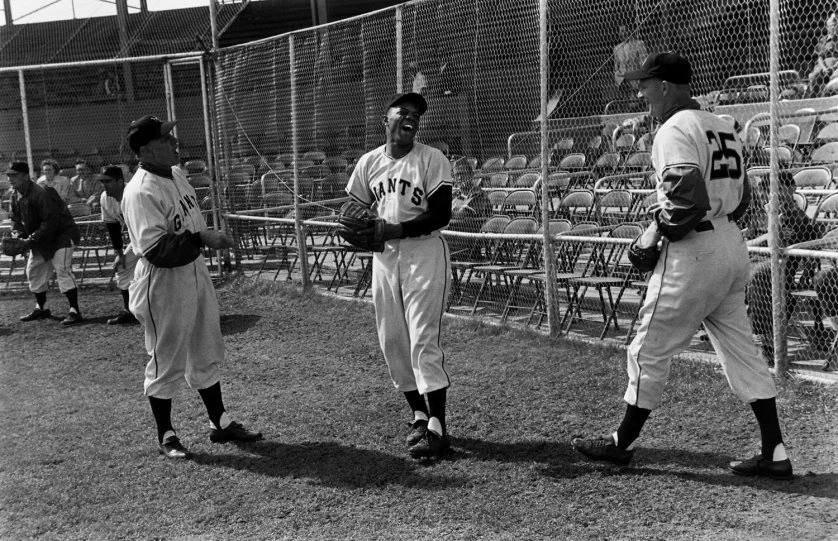

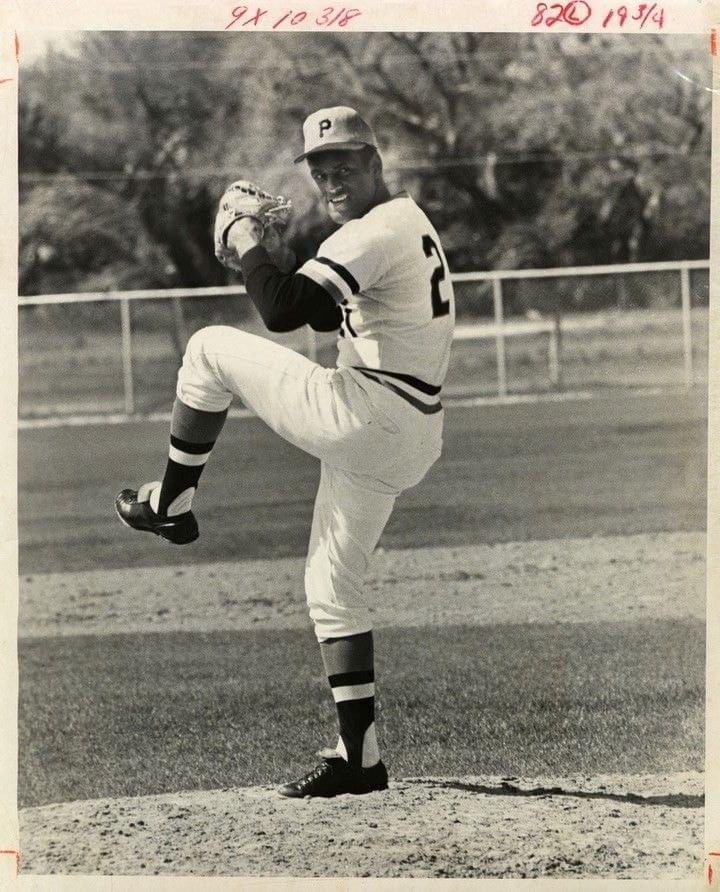

Clemente was even better in 1961, capturing his first of four batting titles with a league-leading mark of .351. He also drove in 89 runs and established new career highs with 23 home runs, 100 runs scored, and 201 hits. The rightfielder placed fourth in the league MVP balloting, earned the second of his 12 All-Star Game nominations, and won the first of his 12 straight Gold Glove Awards for his brilliant outfield play. As Clemente grew increasingly comfortable with American culture, his all-around game continued to expand. Running the bases with a fury rarely seen, playing rightfield with the same flair with which Willie Mays patrolled centerfield for the Giants, and exhibiting tremendous passion for the game, Clemente was one of baseball’s greatest players the remainder of his career. He was particularly outstanding from 1961 to 1967, continuing to excel in all other aspects of the game while also improving upon his power and run-production numbers during the period. After capturing consecutive batting titles in 1964 and 1965, Clemente had perhaps his greatest season in 1966, batting .317, compiling 202 hits, and establishing career highs with 29 home runs, 119 runs batted in, and 105 runs scored, en route to earning league MVP honors. Clemente performed brilliantly again the following year, hitting 23 homers, driving in 110 runs, scoring 103 others, and leading the league with 209 hits and a .357 batting average. He finished third in the MVP voting at season’s end.

After failing to hit .300 for the first time in nine seasons in 1968 (he batted .291), Clemente posted a batting average of .345 the following year, to place a close second to Pete Rose in the N.L. batting race. He also hit 19 home runs, knocked in 91 runs, scored 87 others, and led the league with 12 triples. Clemente finished the 1960s with a .328 batting average – the highest figure posted by any player who competed during the decade.

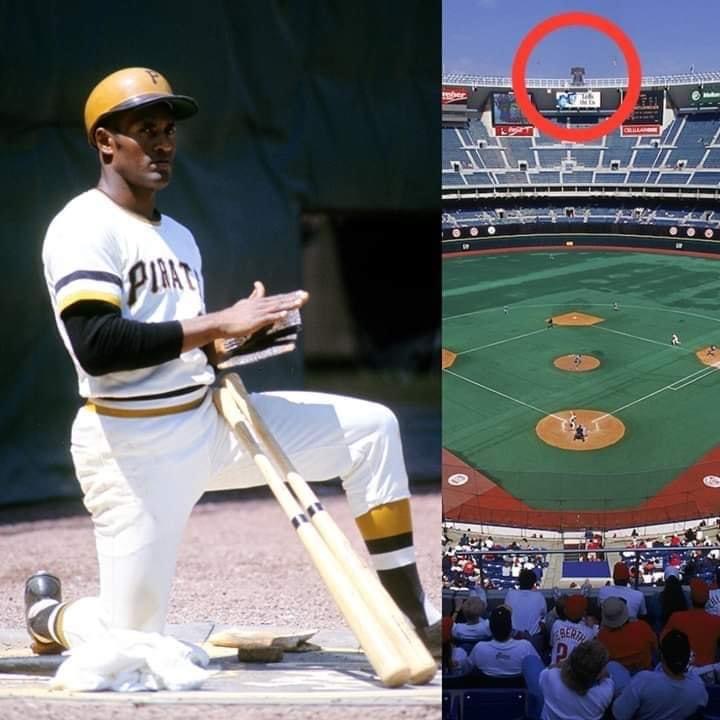

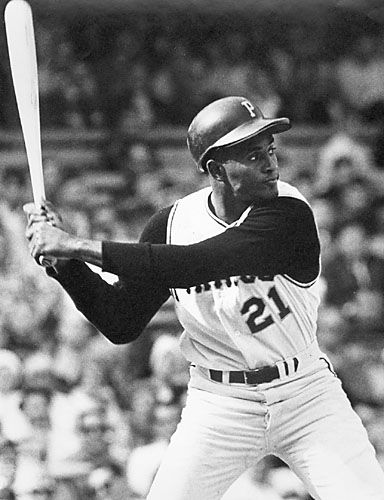

Although known primarily as a line-drive hitter, Clemente actually had outstanding power to all fields. However, his home-run output was generally reduced to some degree by the fact that he spent the majority of his career playing in cavernous Forbes Field, with its distant outfield fences. Had he played in a ballpark more conducive to hitting home runs, Clemente likely would have compiled many more than the 240 homers he accumulated over the course of his career.

San Francisco Giants righthander Juan Marichal noted that one of the things that made Clemente such a difficult hitter for opposing pitchers to face was his ability to hit bad pitches. The Hall of Fame righthander suggested, “The big thing about Clemente is that he can hit any pitch. I don’t mean only strikes. He can hit a ball off his ankles or off his ear.”

Pittsburgh pitcher Steve Blass spoke about the respect other players around the league had for Clemente when he said, “He (Clemente) was the one player that players on other teams didn’t want to miss. They’d run out of the clubhouse to watch him take batting practice. He could make a 10-year veteran act like a 10-year-old kid.”

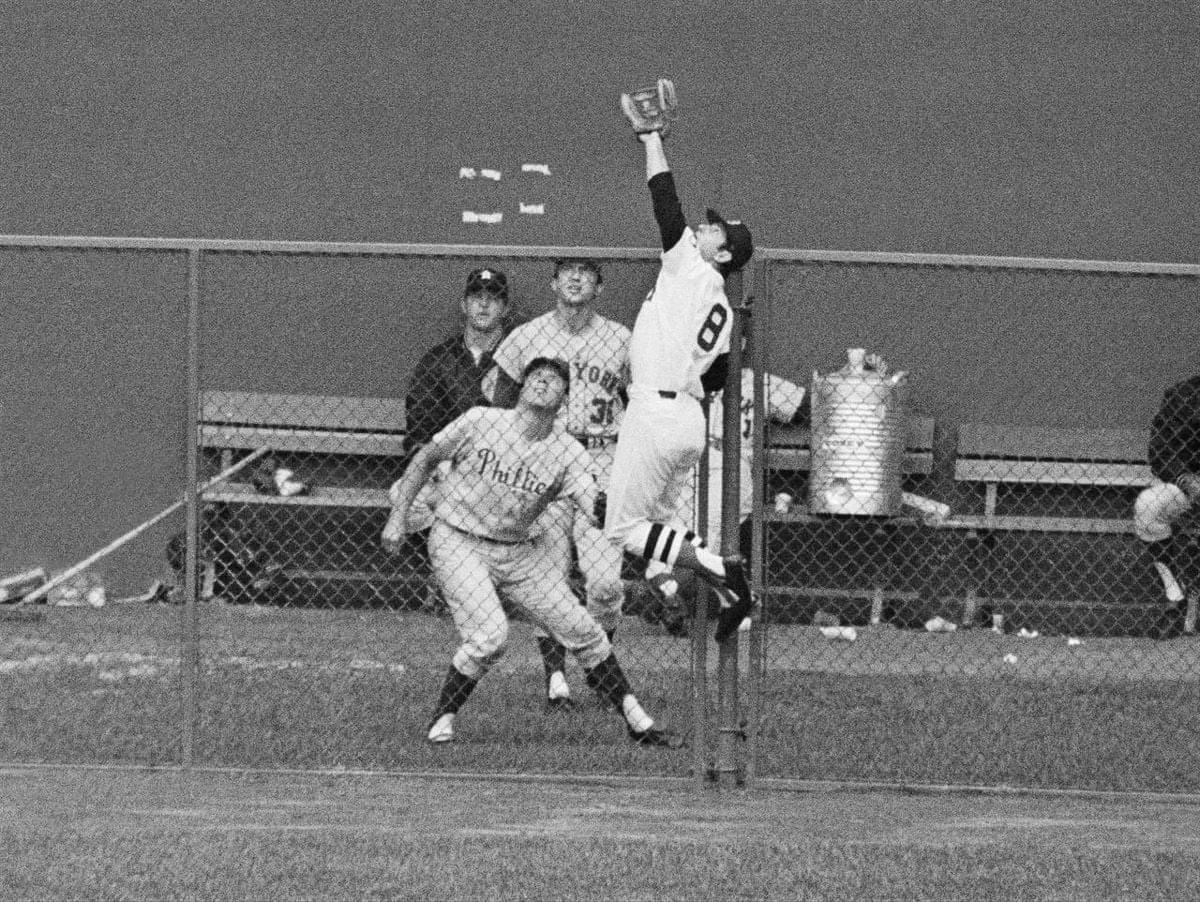

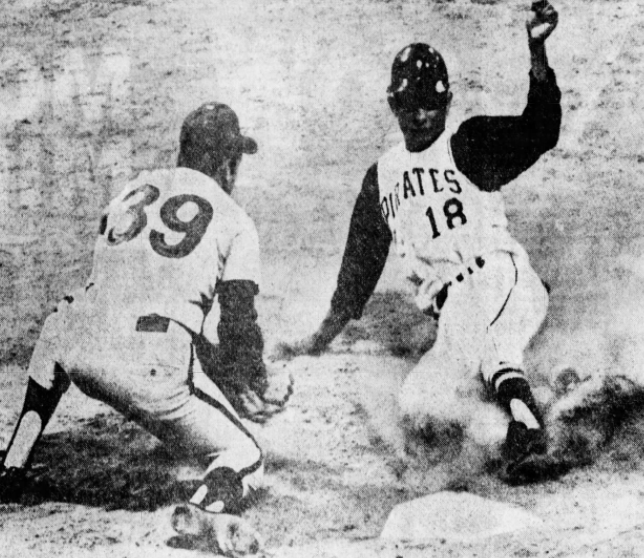

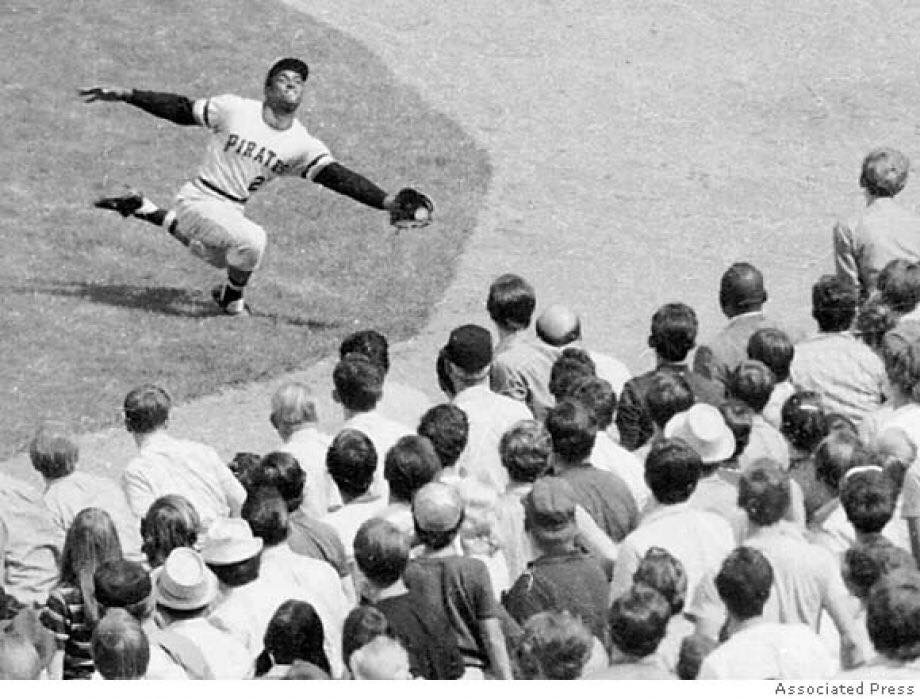

As outstanding as Clemente was at the plate, he may have been even better in the field. The owner of baseball’s strongest throwing arm among rightfielders, Roberto completely intimidated opposing runners on the basepaths. Longtime Dodgers broadcaster Vin Scully once commented, “Clemente could field the ball in New York and throw out a guy in Pennsylvania.”

The arrival of the 1970s did not diminish Clemente’s skills in the least. Although he appeared in only 108 games for Pittsburgh in 1970, the 35-year-old rightfielder helped lead the Pirates to the first of three consecutive N.L. East titles by batting .352. He followed that up by posting a mark of .341 in 1971, en route to finishing fifth in the league MVP balloting. Pittsburgh went on to defeat Baltimore in seven games in the World Series, with Clemente having perhaps his finest moment during the Fall Classic.

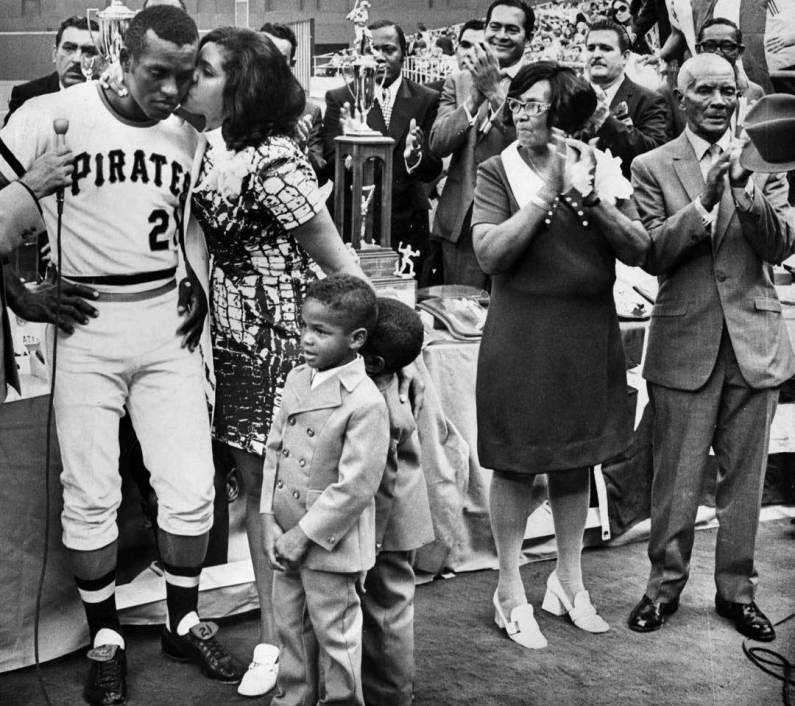

Displaying his considerable talents before a national television audience, Clemente not only captivated the nation with his extraordinary play in right field, but he also dominated the vaunted Baltimore Orioles pitching staff, hitting two home runs and batting .414 in leading his team to victory and capturing Series MVP honors. Baltimore first baseman Boog Powell later said, “No one hit our pitchers like that. Some players might have had the number of one or two of our starters, but no other player dominated our entire staff that way.”

The Pirates’ elder statesman by the early-1970s, Clemente had already helped change the climate in both the Pittsburgh clubhouse, and in the city as a whole by that time. The Pirates were a predominantly white team when Roberto first joined them in 1955, and they remained that way throughout the first half of his career. Black and Latino players were frowned upon by many members of the organization, and they were viewed suspiciously by both the media and the public. But the team became increasingly integrated during the 1960s, with black players such as Willie Stargell, Donn Clendenon, and Al Oliver coming aboard, along with several Latino players such as Matty Alou, Manny Mota, Manny Sanguillen, and Jose Pagan. Clemente’s comfort level began to grow as other players who spoke his native language joined him on the Pirates roster, and he gradually became much more of a team leader than he was earlier in his career. Roberto not only took the other Latin players under his wing, but he also served as mentor to the other young players on the team, such as Stargell. Clemente taught Stargell how to play the game properly, and how to carry himself with dignity and class off the field. Stargell, in turn, passed that knowledge on to the next generation of Pirates players. Towards the end of his career, Clemente commented, “My greatest satisfaction comes from helping to erase the old opinion about Latin Americans and blacks.”

Clemente batted .312 over the course of the 1972 campaign, stroking the 3,000th hit of his career in his final at-bat of the season. Unfortunately, that turned out to be his last hit. Clemente was tragically killed in a plane crash just off the coast of San Juan, Puerto Rico on December 31, 1972 while taking supplies to Nicaraguan earthquake victims. In addition to 3,000 hits, Clemente compiled 240 home runs, 1,305 runs batted in, 1,416 runs scored, and a .317 batting average over his 18 big-league seasons. He surpassed 20 homers three times, 100 runs batted in twice, 100 runs scored three times, and 200 hits on four separate occasions. Clemente led the league in hits twice, and, in winning four batting titles, he topped the .340-mark on five separate occasions. He appeared in 12 All-Star Games, won 12 Gold Gloves, and finished in the top 10 in the league MVP voting a total of eight times.

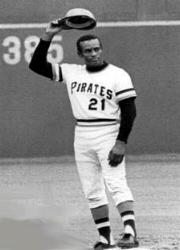

Almost 40 years after his passing, Roberto Clemente remains a legendary figure, particularly among members of the Latino community. Major League Baseball presents an annual Roberto Clemente Award to “the player who best exemplifies the game of baseball, sportsmanship, community involvement and the individual’s contribution to his team.” And as Puerto Rican journalist Luis Mayoral said, “Clemente was our Jackie Robinson. He was on a crusade to show the American public what an Hispanic man, a black Hispanic man, was capable of.”

Former Pirates General Manager Joe L. Brown expressed his admiration for Clemente by saying, “He’s a shining star to many, many people. He grows and grows over time. He doesn’t diminish…The sad part is that there are not enough TV pictures of him. He made so many great plays that people can only talk about. You could never capture the magnificence of the man.”

Former Baseball Commissioner Bowie Kuhn stated in his 1973 eulogy to Clemente, “He (Clemente) gave the term ‘complete’ a new meaning. He made the word ‘superstar’ seem inadequate. He had about him the touch of royalty.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon

Other Resources & Links

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject