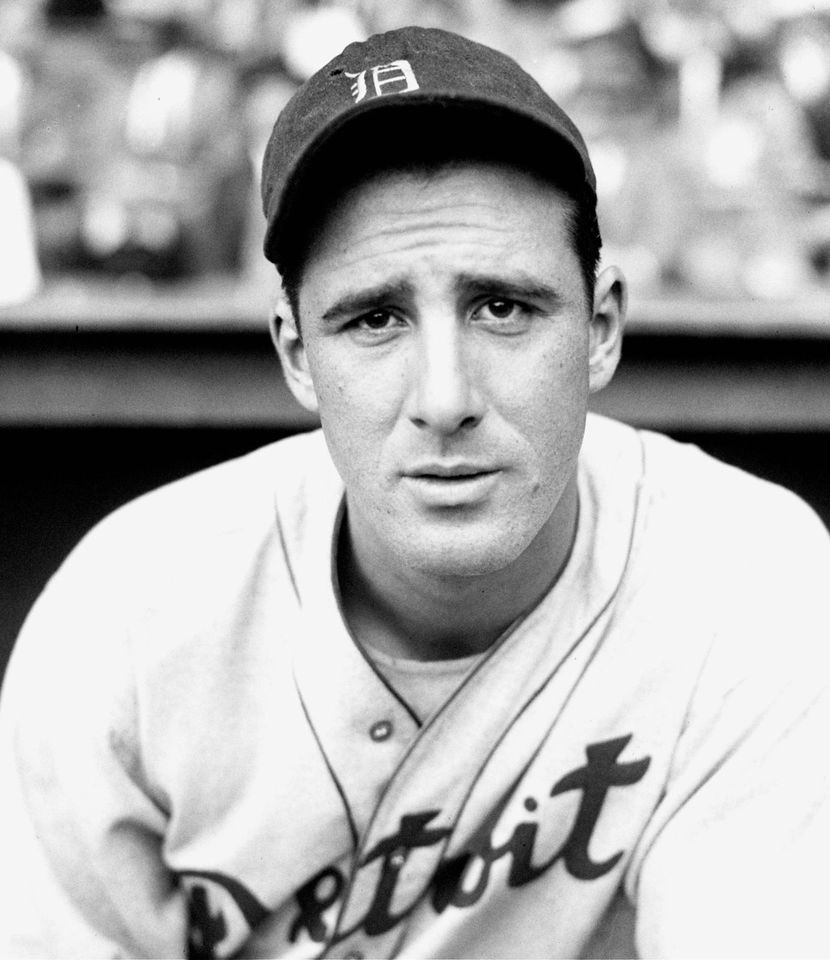

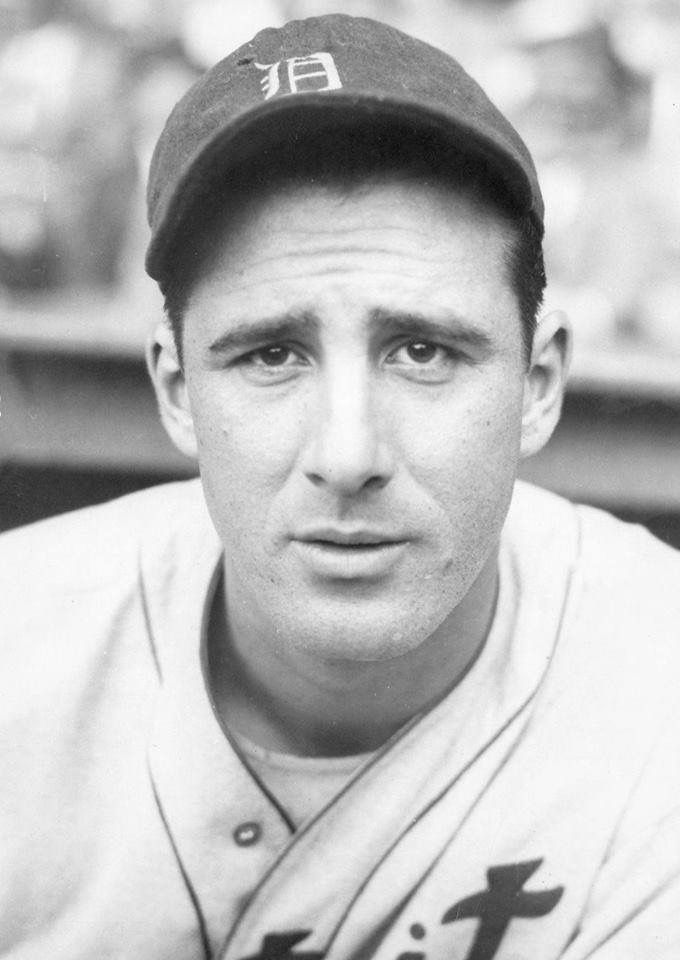

Hank Greenberg Stats & Facts

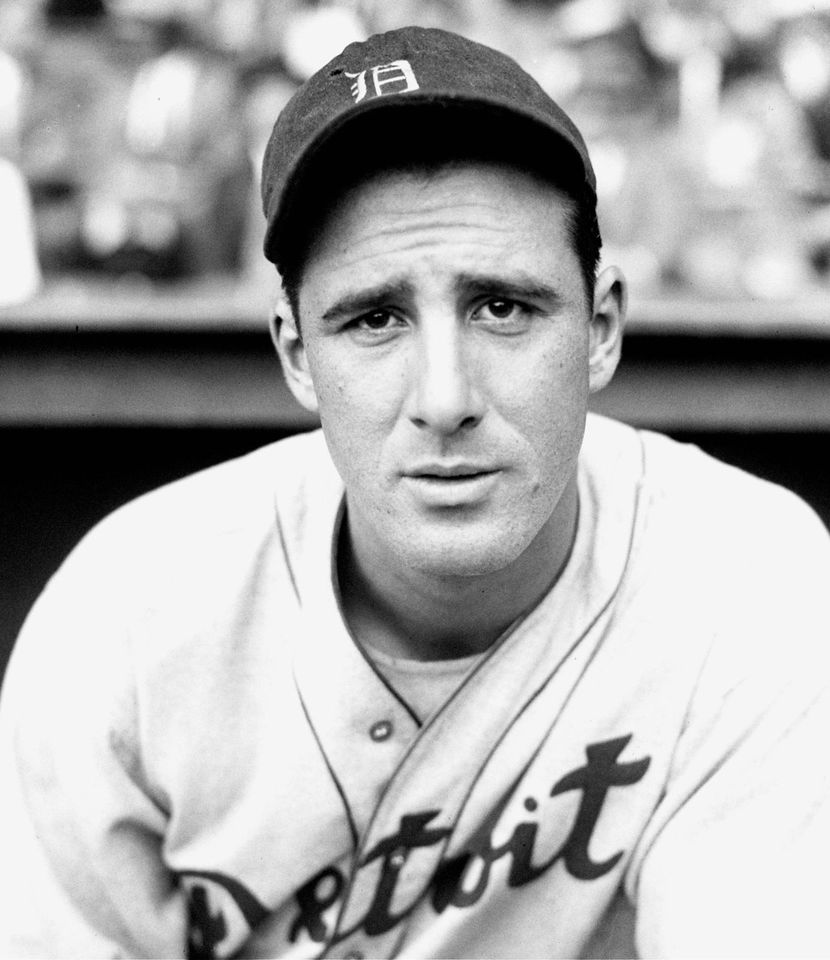

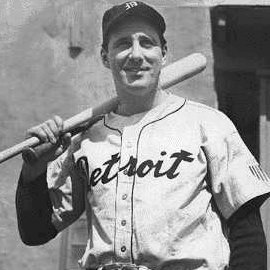

Hank Greenberg

Positions: First Baseman and Leftfielder

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-3, 210lb (190cm, 95kg)

Born: January 1, 1911 in New York, NY

Died: September 4, 1986in Beverly Hills, CA

Buried: Hillside Memorial Park, Los Angeles, CA

High School: James Monroe HS (New York, NY)

School: New York University (New York, NY)

Debut: September 14, 1930 (7,128th in major league history)

vs. NYY 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 18, 1947

vs. BRO 3 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1956. (Voted by BBWAA on 164/193 ballots)

View Hank Greenberg’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Nicknames: Hammerin’ Hank

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Other Players Who Debuted in 1930

Luke Appling

Joe Kuhel

Pinky Higgins

Ben Chapman

Hank Greenberg

Lon Warneke

Tommy Bridges

Lefty Gomez

Dizzy Dean

All-Time Teammate Team

Coming Soon

Notable Events and Chronology for Hank Greenberg Career

Biography

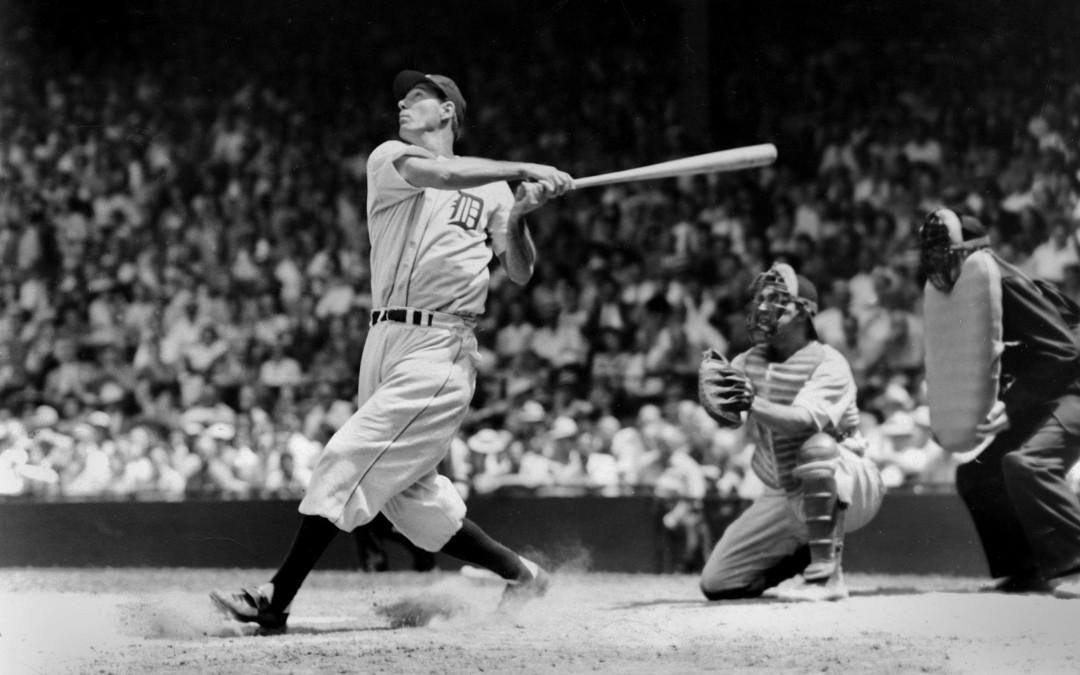

Had he not spent much of his career competing against arguably the two greatest first basemen in baseball history in Lou Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx, Hank Greenberg likely would receive far more recognition for having been one of the most prolific sluggers in baseball history. Greenberg’s legacy was further diminished by the fact that he spent almost five full peak seasons serving his country during World War II. Nevertheless, despite playing the equivalent of only nine-and-a-half full seasons in the major leagues, the big first baseman hit 331 home runs, drove in 1,276 runs, won two American League Most Valuable Player Awards, and led the Detroit Tigers to four pennants and two world championships, en route to establishing himself as one of the premier sluggers the game has ever seen.

Biography:

Born in New York City’s Greenwich Village on January 1, 1911 to Rumanian-born Orthodox Jewish immigrants who owned a successful cloth-shrinking plant, Henry Benjamin Greenberg moved with his family to the Bronx when he was seven years old.

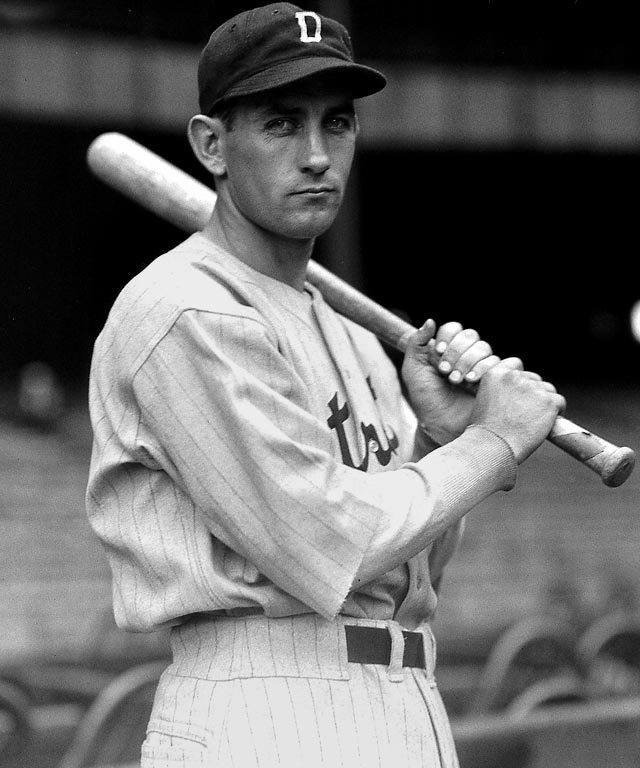

Hampered by flat feet and a lack of coordination as a youngster, Greenberg worked diligently to overcome his physical deficiencies. After graduating from James Monroe High School in the Bronx, Hank attended New York University on an athletic scholarship for one semester before choosing to leave school to pursue a career in baseball.

Standing 6’4″, weighing 220 pounds, and possessing great physical strength, Greenberg seemed to have all the physical tools he needed to succeed at the major league level. Yet he remained unsure of himself, especially early in his career, viewing his size and lack of grace as a major obstacle to his success. Greenberg’s high school baseball coach explained, “Hank was so big for his age and so awkward that he became painfully self-conscious. The fear of being made to look foolish drove him to practice constantly and, as a result, to overcome his handicaps.”

Greenberg’s hard work paid off in the end, with the Giants, Yankees, and Senators all courting him before he finally elected to sign with the Detroit Tigers in January, 1930. The big first baseman spent the next three years in Detroit’s minor league farm system, excelling at Raleigh, North Carolina in 1930, Evansville in the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa League in 1931, and Beaumont in the Texas League in 1932. It was at Beaumont that Greenberg received his first true dose of anti-Semitism.

At one point during the season, one of Greenberg’s teammates (Jo-Jo White) began staring at the first baseman as he circled him slowly. When Greenberg asked White why he was staring at him, his teammate replied that he was merely curious, since he had never seen a Jew before. Greenberg later revealed, “I let him keep looking for a while, and then I said, ‘See anything interesting?'” Looking for horns and finding none, White responded, “You’re just like everyone else.”

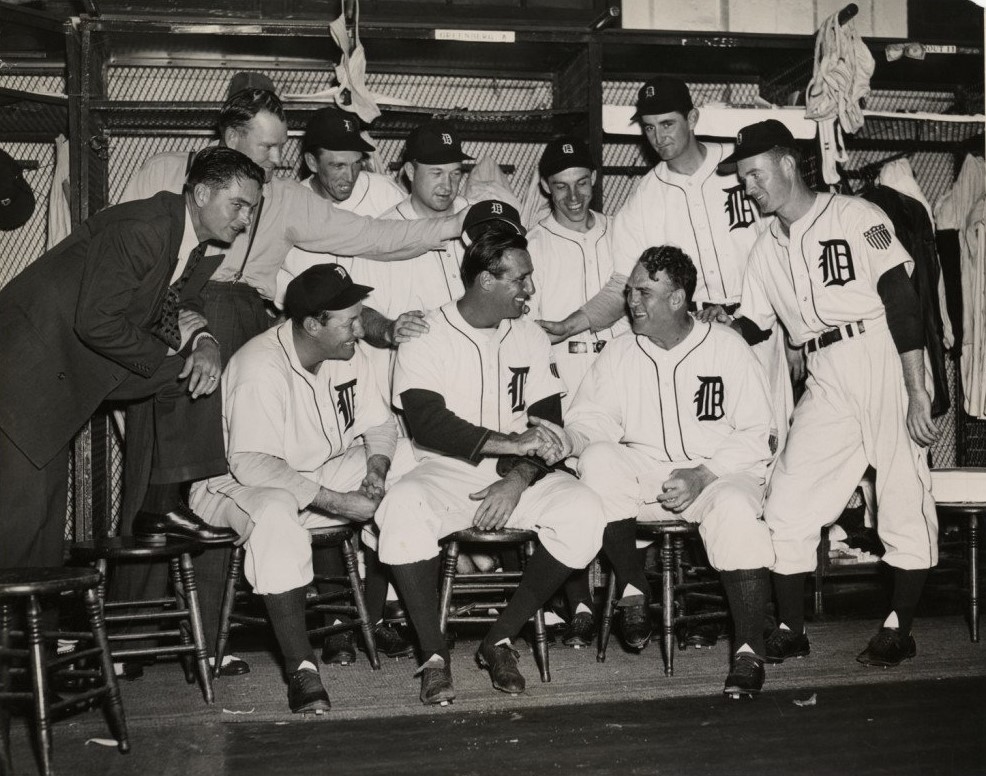

Greenberg joined Detroit in 1933, displaying from the very beginning his abilities as a hitter. He knocked in 87 runs and batted .301 in his 117 games as a rookie, teaming up with second baseman Charlie Gehringer to give the Tigers a deadly right side to their infield. Although Greenberg was still a bit raw in the field, he worked extremely hard on his defense, eventually turning himself into an above-average defensive first baseman.

Greenberg had his breakout year in 1934, helping the Tigers to 101 victories and the American League pennant by hitting 26 home runs, driving in 139 runs, scoring 118 others, batting .339, accumulating 201 hits, and topping the circuit with 63 doubles. He finished sixth in the league MVP voting. Detroit lost the World Series to St. Louis in seven games, but Greenberg acquitted himself quite well, batting .321, with nine hits, seven runs batted in, and a home run.

Late in the year, though, Greenberg inspired a considerable amount of controversy when he announced he did not intend to play on either Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, or Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement. With the Tigers in the middle of a pennant race, Detroit fans grumbled, “Rosh Hashanah comes every year, but the Tigers haven’t won the pennant since 1909.” After doing much soul-searching, Greenberg decided to play on Rosh Hashanah, but he elected to sit out the game Detroit had scheduled for Yom Kippur. After the first baseman hit two home runs during the Tigers’ 2-1 pennant-clinching victory played on the Jewish New Year, the Detroit Free Press ran the Hebrew lettering for “Happy New Year” across its front page the next day. Meanwhile, columnist and poet Edgar A. Guest wrote a poem entitled “Speaking of Greenberg” that ended with the lines “We shall miss him on the infield and shall miss him at the bat / But he’s true to his religion – and I honor him for that.”

In truth, Greenberg was not a particularly religious man, but, as the first true Jewish star in professional sports, he considered it his duty to set a good example for his people, and to be a positive role model for the Jewish youth of America. After his playing career was over Greenberg revealed, “When I was playing, I used to resent being singled out as a Jewish ballplayer. I wanted to be known as a great ballplayer, period. I’m not sure why or when I changed, because I’m still not a particularly religious person. Lately, though, I find myself wanting to be remembered not only as a great ballplayer, but even more as a great Jewish ballplayer.”

The Detroit first baseman established himself as one of baseball’s elite players in 1935, leading the Tigers to their second consecutive pennant by placing among the league leaders with a .328 batting average, 121 runs scored, 203 hits, 16 triples, 46 doubles, and a .628 slugging percentage, while topping the circuit with 36 home runs and 170 runs batted in. His outstanding performance earned him league MVP honors.

The Tigers subsequently defeated the Chicago Cubs in six games in the World Series, but the Fall Classic was not a particularly enjoyable one for Greenberg. The A.L. MVP badly injured his wrist in the second contest, and he subsequently had to sit out the four remaining games. Even prior to that unfortunate incident, though, the treatment Greenberg received from the Chicago players left him feeling somewhat disconcerted. The Cubs took every opportunity to remind the big first baseman of his Jewish heritage, hurling ethnic slurs at Greenberg whether he was at the bat or in the field. As the slugger stood at home plate on one particular occasion waiting for the opposing pitcher to deliver his pitch, one Chicago player yelled, “Throw him a porkchop…he can’t hit that!” The abuse eventually got so bad that home plate umpire George Moriarty stopped the game and instructed the Cubs to tone down their remarks.

Such shabby treatment of Greenberg was not at all unusual, especially early in his career. Anti-Semitism ran rampant throughout the United States at the time, and Detroit was actually one of the nation’s least-tolerant places. Henry Ford, one of the city’s leading citizens, harbored deep resentment towards people of the Jewish faith. He published The International Jew during the 1920s, a work that blamed a Jewish conspiracy for both communism and a capitalistic plot designed to destroy Christian civilization. And Father Coglin expressed pro-Nazi sentiments while simultaneously denouncing Jews and blacks during his weekly radio shows that were broadcast throughout the city.

Things being as they were in this country during Greenberg’s playing days, he often had to endure verbal abuse from fans and opposing players alike. The big first baseman was not the first Jewish man to play in the major leagues. But he was one of a select few who elected not to conceal his heritage by changing his name, and he was certainly the first truly great Jewish player to don a big-league uniform. As a result, Greenberg became a symbol of success for many Jewish-Americans, as much as he became a target of abuse for those people who resented him merely because of his faith. Greenberg usually chose to ignore the many derisive comments that were directed towards him, but he sometimes elected to retaliate when his adversary pushed him too far.

One such instance occurred during a game against the Chicago White Sox. With Greenberg holding on Chicago baserunner Joe Kuhel at first base, the White Sox first baseman attempted to spike his counterpart as he slid back to the bag on an attempted pick-off. Greenberg responded by slapping Kuhel, but the confrontation was quickly broken up before it was allowed to escalate. However, Greenberg followed the White Sox players into their clubhouse at the conclusion of the game and proceded to berate Kuhel in front of the entire team. No one on the White Sox moved a muscle as the hulking Greenberg continued to convey his anger to Kuhel, who sat quietly through the entire diatribe. Detroit pitcher Eldon Auker followed his teammate into the Chicago clubhouse and observed the entire episode. Auker later recalled that the Chicago player’s submissive attitude during the reproach “…was probably a good thing because Hank was real tough.”

Following Detroit’s World Series victory in 1935, Greenberg re-injured his wrist early in the 1936 campaign and missed virtually the entire year. He returned, though, in 1937 to have one of his finest seasons. In addition to hitting 40 home runs, batting .337, scoring 137 runs, and amassing 49 doubles and 200 hits, Greenberg knocked in 183 runs, to come within one RBI of tying Lou Gehrig for the all-time American League record. The Tiger first baseman finished third in the league MVP balloting.

Greenberg placed third in the MVP voting again in 1938, when he batted .315, drove in 146 runs, led the league with 144 runs scored, and topped the circuit with 58 home runs, to finish two homers shy of Babe Ruth’s then single-season mark of 60.

Although Greenberg continued to reject the notion years later, some of his Tiger teammates believed that opposing pitchers refused to pitch to the slugger during the season’s final days because they didn’t want a Jewish player to break the Babe’s record.

Greenberg had another very solid year in 1939, hitting 33 home runs, knocking in 112 runs, scoring another 112, and batting .312. He then became the first player to win the Most Valuable Player Award at two different positions in 1940, after he moved to left field prior to the start of the season to make room at first base for young slugger Rudy York. Greenberg ended up leading the Tigers to the pennant by batting .340, scoring 129 runs, and topping the circuit with 41 home runs, 150 runs batted in, 50 doubles, and a .670 slugging percentage. Although the Tigers subsequently lost the World Series to the Reds in seven games, Greenberg batted .357, with 10 hits, one home run, six runs batted in, and five runs scored.

Greenberg’s strong anti-Nazi sentiments prompted him to become the first major league player to enlist in the United States military at the beginning of the second World War. Initially drafted in 1940, Greenberg spent all but the first 19 games of the 1941 campaign serving his country, before being honorably discharged on December 5, 1941, after the United States Congress elected to release men aged 28 years and older from service. However, Greenberg elected to re-enlist immediately when the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor just two days later. After graduating from Officer Candidate School, he was commissioned as a first lieutenant in the United States Army Air Forces. Greenberg eventually served overseas in the China-Burma-India Theater, scouting locations for B-29 bomber bases. He remained on active duty until he was finally discharged four-and-a-half years later, in mid-1945.

Greenberg showed little rust when he returned to the Tigers, homering in his first game back, driving in 60 runs in only 78 games, and clinching the pennant for Detroit with a grand slam home run in the final game of the season. He then hit two home runs and knocked in seven runs against the Cubs in the World Series, leading the Tigers to a seven-game victory.

Greenberg spent only one more year in Detroit, leading the American League with 44 home runs and 127 RBIs in 1946. He was traded to the Pirates at the end of the season, and he spent his final year in Pittsburgh mentoring future Hall of Famer Ralph Kiner.

Greenberg later said, “Ralph had a natural home run swing. All he needed was somebody to teach him the value of hard work and self-discipline. Early in the morning on off-days, every chance we got, we worked on hitting.” Kiner went on to hit 51 home runs for the Pirates that year, and he later gave Greenberg much of the credit for the success he experienced during his Hall of Fame career.

Greenberg retired at the end of the 1947 campaign to take a front-office position with the Cleveland Indians. He ended his career with a .313 batting average, 331 home runs, and 1,276 RBIs in only 1,394 games. He surpassed 40 homers on four separate occasions, knocked in more than 100 runs seven times, scored more than 100 runs six times, collected more than 40 doubles five times, and amassed more than 200 hits three times. Greenberg averaged 39 home runs, 150 runs batted in, and 127 runs scored in the six full seasons he played between 1934 and 1940, while also batting well over .300 each year. He led the A.L. in home runs and runs batted in four times each, and he also topped his circuit once in runs scored, and twice in both doubles and walks. He was selected to appear in the All-Star Game a total of five times.

After serving as Cleveland’s farm director in 1948 and 1949, Greenberg became the team’s general manager in 1950. A shrewd judge of talent, he subsequently helped build the Indians team that won 111 games in 1954, to put an end to New York’s five-year reign as American League champions. From Cleveland, Greenberg moved on to the Chicago White Sox as part owner and vice president. While with Chicago, Greenberg was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame, being inducted in 1956. He retired from baseball in 1963 to become a successful investment banker. Greenberg remained a physically strong and imposing figure until he developed cancer in the 1980s. He finally lost his battle with the dreaded disease in 1986, passing away in Beverly Hills, California at the age of 75.

Long after his passing, Hank Greenberg continues to be largely overlooked when conversations arise concerning the all-time greats. But the men who saw him play know that he was a truly devastating hitter.

Joe DiMaggio once said of Greenberg: “He was one of the truly great hitters, and when I first saw him bat, he made my eyes pop out.”

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Coming soon

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.