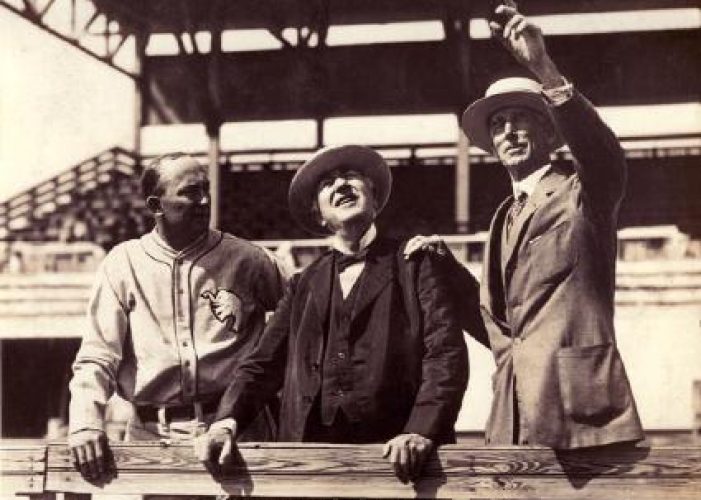

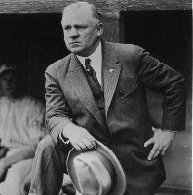

Connie Mack

Positions: Catcher, First Baseman and Rightfielder

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

6-1, 150lb (185cm, 68kg)

Born: December 22, 1862 in East Brookfield, MA us

Died: February 8, 1956 in Philadelphia, PA

Buried: Holy Sepulchre Cemetery, Cheltenham, PA

Debut: September 11, 1886 (1,151st in major league history)

Last Game: August 29, 1896

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Manager in 1937. (Voted by Centennial Committee)

Induction ceremony in Cooperstown held in 1939.

View Connie Mack’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Rookie Status: Exceeded rookie limits during 1887 season

Full Name: Cornelius Alexander Mack

Nicknames: The Grand Old Man of Baseball or The Tall Tactician

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Relatives: Father of Earle Mack

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1886

Coming soon…

Notable Events and Chronology for Connie Mack Career

Connie Mack Intro

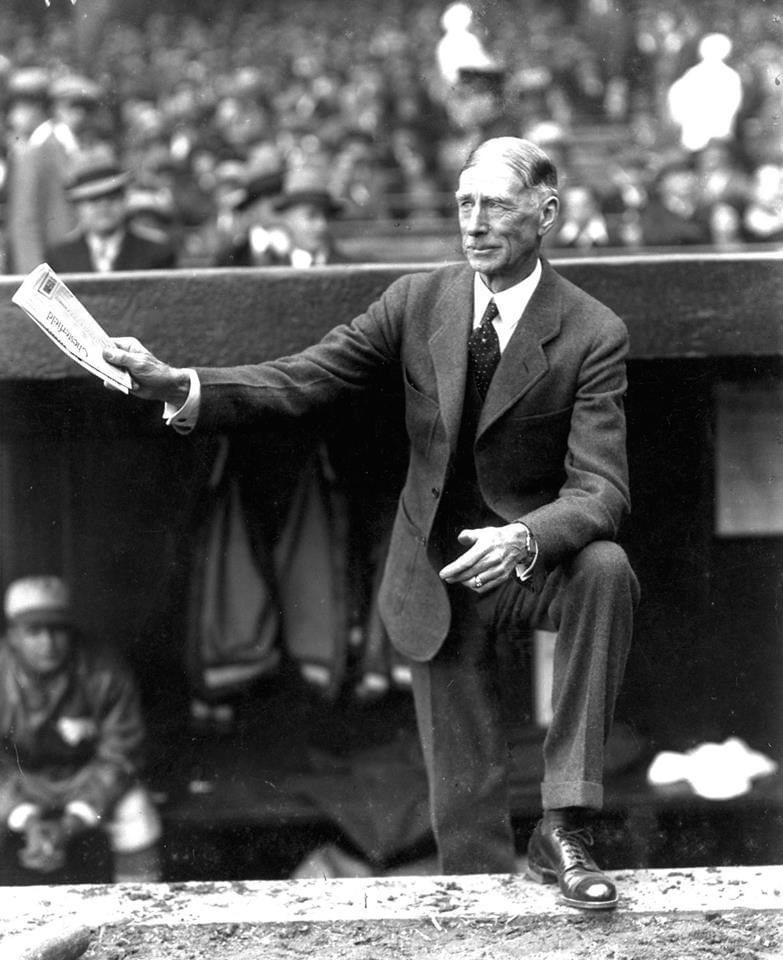

Player, manager, scout, general manager, owner — Cornelius MacGillicuddy (Connie Mack) — did it all. For more than half a century he owned and managed the Philadelphia A’s — nearly their entire existence. He built two dynasties that won a total of five World Series titles, and he still holds the unbreakable records for most games managed, won, and lost.

Unform Number

Mack played in an era when there were no uniform numbers, and when he managed he wore a business suit.

Quotes From

“I like a noisy ball club. In fact, I insist upon it. A team that is making a lot of noise is on its toes and hustling. It suggests that you want to win, have plenty of pep and ginger.”

Best Season

This team featured several future Hall of Fame members and outdistanced the Ruth/Gehrig Yankees by an incredible 18 games. They won 104 games and went on to win the World Series over the Chicago Cubs. This team had great offense — Jimmie Foxx, Mickey Cochrane, Al Simmons — but was really built on pitching and defense. The A’s led the league in ERA (3.44, more than a half-run lower than their closest rival), saves, and runs allowed. While they scored 901 runs, they allowed just 615 and committed the fewest errors (146) in baseball. The staff was led by Lefty Grove (20 wins) and George Earnshaw (24). Grove topped the circuit with a 2.81 ERA and 180 strikeouts. Earnshaw finished second in K’s and 4th in ERA. All the starters, which included Rube Walberg (18-11) and Jack Quinn (11-9), took turns saving games as well. Eddie Rommel was 12-2 out of the bullpen, and Bill Shores was 11-6 with 7 saves. Essentially the same team won the next two pennants, Mack’s last as manager.

Factoid 1

Connie Mack served as manager for the American League in the first All-Star Game, in 1933.

Strengths

Mack, a tall stolid man, had the absoulte respect of every man who ever played for him.

Weaknesses

Fiscal acumen.

Feats

Mack holds the all-time record for most games managed (7,755), most games won (3,7531), and most games lost (3,814). His record of 50 years managing one team, and 53 years overall will most likely never be broken.

Description

Mack was often described as the “grand old gentleman of the game,” but he wasn’t above stretching the rules to gain a competitive advantage. He was rumored to have kept frozen baseballs handy to insert into the game when his pitcher’s were on the mound. He also employed a special coach who stationed himself in center field at Shibe Park to steal signs from opposing teams.

Hall of Fame Outfield

In 1928, Mack signed star outfielder Tris Speaker, who was at the end of his remarkable career. Speaker joined Ty Cobb and Al Simmons in the A’s outfield, giving Mack three future Hall of Famers in his outer region.

History of the “White Elephant”

In 1901, Connie Mack and his Philadelphia Athletics helped form the American League. The following year, New York Giants Manager John McGraw dismissed the A’s with contempt, calling them “The White Elephants.” In response, Mack defiantly adopted the White Elephant as the team insignia, and it has been part of the franchise’s heritage ever since. Its first appearance was on team sweaters. In about 1918, the Elephant finally saw game action when Mack had the pachyderm symbol (in blue with a white “A” inside) placed on the left sleeve of every player. By 1920, Mack had fully adopted the A’s Elephant as the team’s symbol. Gone was the traditional A” on the front of the jersey. In its’ place was a blue elephant logo. But after a few poor seasons, Mack decided a change was in order. So, in 1924, the blue elephant was replaced by the white elephant on the team’s jersey. The new-look pachyderm seemed to do the trick, as the A’s played better ball for the next few years. In 1928, Mack decided the elephant had worn out its brief welcome on the A’s jersey fronts. He replaced it with the familiar “A” on the uniforms, and the A’s went on to win two World Championships and an AL crown in the next three years. This resurgence was probably due more to the additions of Jimmie Foxx, Al Simmons, Lefty Grove, Mickey Cochrane, et al., than to the elephant’s absence. That was the last year for the elephant on the A’s uniform until 1955, when the A’s, now in Kansas City, added an elephant patch to their left sleeves. But when Charlie Finley purchased the team in the early sixties, the elephant mascot was once again sent packing, replaced by, of all animals, a mule. This was the last we saw of this loveable A’s mascot until 1988, when the elephant proved to be a “good luck” charm for the A’s, as the team, now in Oakland, won three straight American League pennants and one world championship.

The “$100,000 Infield”

Connie Mack pieced together a tremendous baseball team in the first decade of the 20th century, built in large part, around his famous “$100,000 Infield.” At the time, Mack claimed that even that lofty dollar-amount would not pry the four star players away from him. In 1911, John “Stuffy” McInnis was switched to first base to replace the aging Harry Davis, a fine player. McInnis, who earned his nickname because he had the “right stuff” as a young ballplayer in Boston, joined Eddie Collins, Jack Barry, and Frank Baker to form the greatest infield of the era. The move was somewhat surprising in that McInnis was just 5-foot-9 — the same size as the diminutive Collins and Barry. Most first basemen were tall and lanky, but using the sure hands that had once guided him as a shortstop, McInnis quickly became a solid first sacker. He would lead his league in fielding six times. Eddie “Cocky” Collins was a star at second base, with great speed and a sure pivot. He still holds the major league record for most games played at second, most chances, most assists, and most putouts. In 1914, he won the Chalmers Award as the best player in the American League. At various times he led the AL in steals, OBP, runs, and walks. He was a clutch performer, batting .328 in six World Series and setting a record with 14 steals in the Fall Classic. The shortstop of the $100,000 Infield is the least remembered of the foursome. John “Jack” Barry was born in Connecticut — like the other three members of the infield he was an easterner. He came to the A’s from the campus of Holy Cross, similar to Collins journey from Columbia University. Before long, the two college men meshed in the middle of Mack’s diamond, forming the best double play duo in baseball. Barry was known as a clutch hitter despite his .243 career average — no AL shortstop drove in more runs than he did from 1909 to 1917. At third base in the famous infield was Frank “Home Run” Baker, the most explosive hitter of the quartet. Baker wasn’t known for his fielding, but his bat more than made up for it. He led the American League in home runs every season from 1911 to 1914. In 1912 and 1913 he also paced the circuit in RBI. During his time as an everyday player, from 1909 to 1919, only Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, and Collins collected more hits in the AL. No player in his league hit more homers than Baker did over that stretch (80), and only Cobb had more RBI. The four infielders teamed for four pennants and three World Titles (1910, 1911, and 1913) in Philadelphia and also enjoyed success after they left the A’s. Collins won a World Series with the White Sox in 1917 and played in another Fall Classic in 1919. His post-season performances were legendary, and he gathered four World Series championships. After leaving the A’s, McInnis started at first base and led the league in fielding for the 1918 World Champion Boston Red Sox. In the Series that year, while the rest of his team batted .178, he hit .250 in the six-game win. In 1925, he found himself with the NL Champion Pittsburgh Pirates and hit .368 with 24 RBI in 59 games as a pinch-hitter and backup first baseman. In the World Series he collected four hits in four games, batted .286, as the Bucs won their first World Title. In all, McInnins was a key member of five World Seriesw-winning teams. Barry played for the 1915 and 1916 Red Sox World Series winning teams, giving him five World Series titles in seven seasons. In the 1911 Series with the A’s, he batted .368 (7-for-19) with four doubles. In 1913, he hit .300 (6-for-20) with three doubles. In 25 World Series games he collected nine doubles, a record when he retired that still ranks third on the all-time list. Baker hit .363 with a .538 slugging percentage in 25 World Series games. In the 1910 Series he batted .409, and in 1911 he hit .375 with home runs on consecutive days off Rube Marquard and Christy Mathewson to earn his nickname. In 1913, Baker was a one-man wrecking crew, damaging Giant pitching at a .450 (9-for-20) clip with seven RBI in five games. He played on the three Athletics Championship teams as well as the 1921 and 1922 Yankee pennant winning clubs. Combined, the four members of the $100,000 Infield appeared in 12 of the 16 World Series played from 1910 to 1925, and were on the winning side eight times. They played in 104 World Series games, collected 109 hits, batted .294, and scored 50 runs. Both Collins and Baker were inducted into the Hall of Fame. We can only imagine what price tag would be put on the $100,000 Infield today.

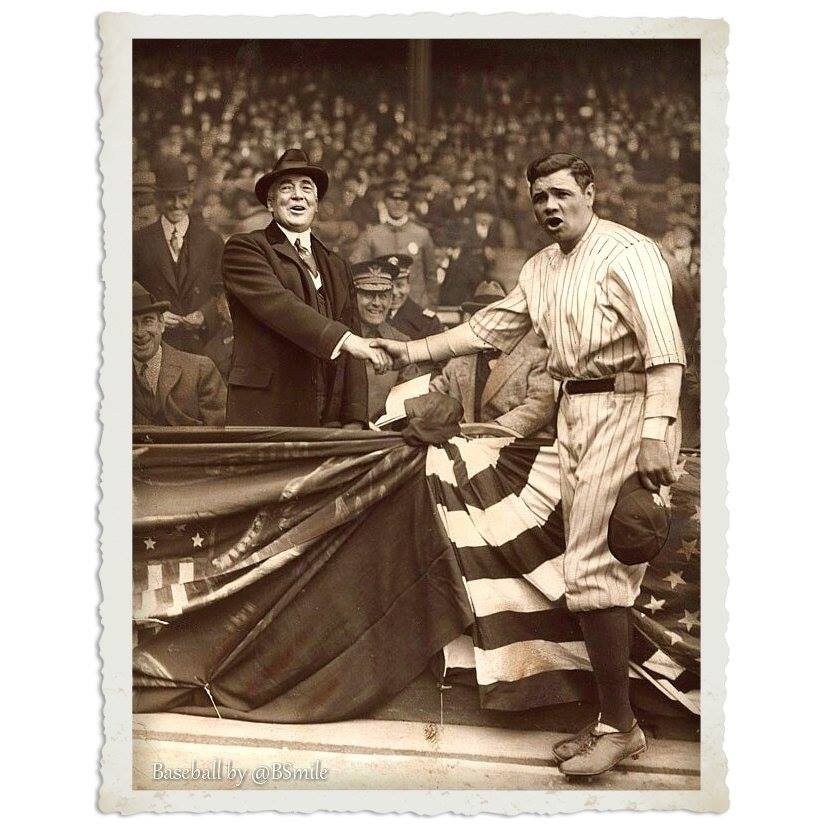

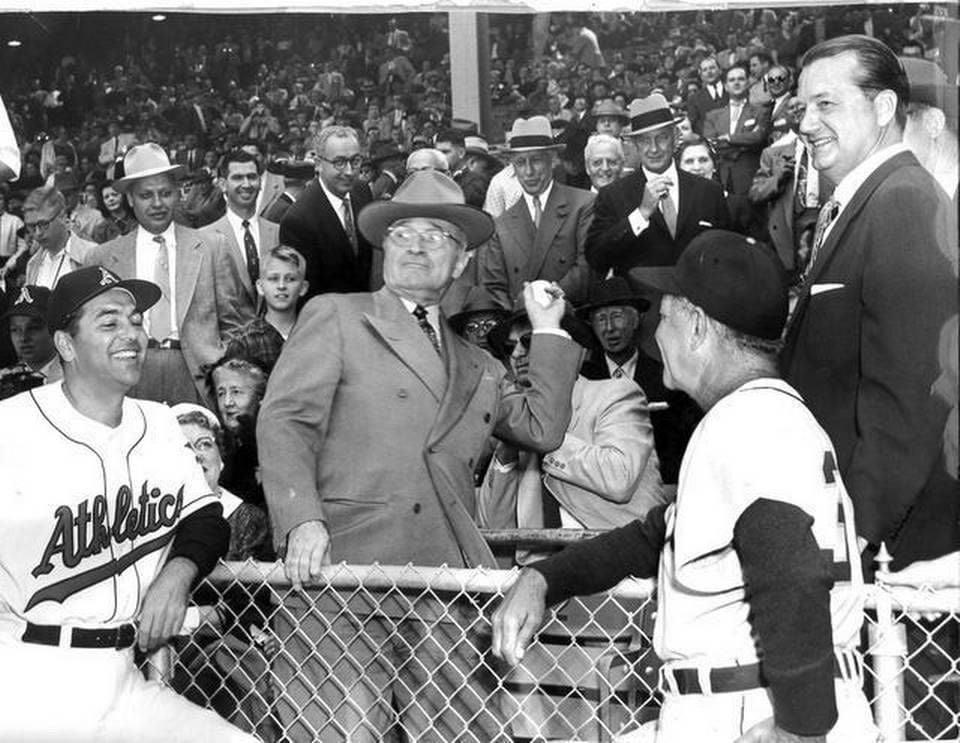

Connie Mack Day at Yankee Stadium

In 1949, the Yankees turned their annual Old-Timers Day into a Connie Mack tribute. As part of the festivities, 86-year old Mack was asked to name his All-Time A’s team, with those players invited by the Yankees to play against the Bronx Bombers old-timers. Mack chose catcher Mickey Cochrane, first basemen Jimmy Foxx and Stuffy McInnis, second baseman Eddie Collins, third baseman Frank Baker, shortstop Jack Barry, outfielders Al Simmons, Mule Haas and Bing Miller, and pitcher Lefty Grove. The old-time Yankees included Bill Dickey, Wally Pipp, Frankie Crosetti, Bob Meusel, Ben Chapman, and Lefty Gomez.

Notes

In 1929, Mack was presented with the Bok Award. The award was named for wealthy Philadelphia financier, Edward Bok and presented to the Philadelphian who was considered to be the most outstanding citizen of the year. It was the first time a sports figure received the honor. The award is on display in the Philadelphia Athletics Historical Association Museum in Hatboro, Pennsylvania.

Other Resources & Links