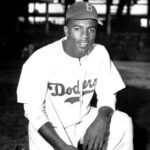

Jackie Robinson Career Highlights

Baseball is the only game you can watch on the radio. Join the community today and listen to hundreds of broadcasts from baseball’s golden age!

Sign Up or learn more

Jackie Robinson Career Highlights

Positions: Second Baseman, Third Baseman and First Baseman

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

5-11, 195lb (180cm, 88kg)

Born: January 31, 1919 in Cairo, GA

Died: October 24, 1972 (Aged 53-267d) in Stamford, CT

Buried: Cypress Hills Cemetery, Brooklyn, NY

High School: Muir Technical (Los Angeles, CA)

Schools: Pasadena City College (Pasadena, CA), University of California, Los Angeles (Los Angeles, CA)

Debut: 1945 (9,801st in major league history)

AL/NL Debut: April 15, 1947

vs. BSN 3 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 30, 1956

vs. PIT 4 AB, 1 H, 1 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1962. (Voted by BBWAA on 124/160 ballots)

View Jackie Robinson’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Jack Roosevelt Robinson

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1947

Nellie Fox

Duke Snider

Larry Doby

Jackie Robinson

Curt Simmons

Mel Parnell

Vic Wertz

Ted Kluszewski

Ferris Fain

All-Time Teammate Team

C: Roy Campanella

1B: Gil Hodges

2B: Junior Gilliam

3B: Billy Cox

SS: Pee Wee Reese

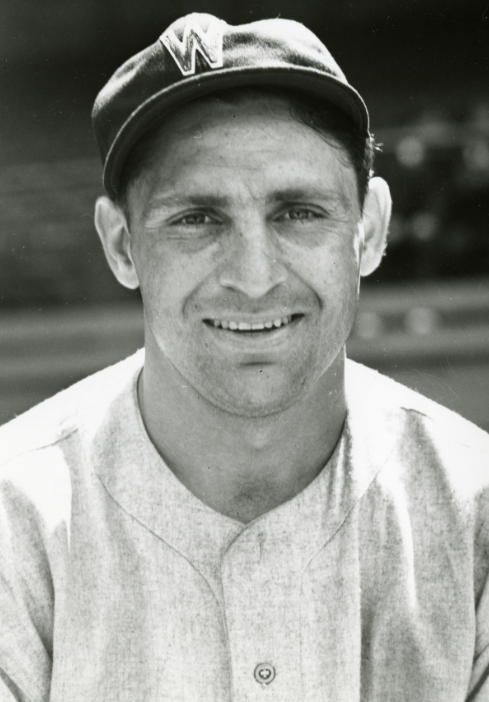

LF: Dixie Walker

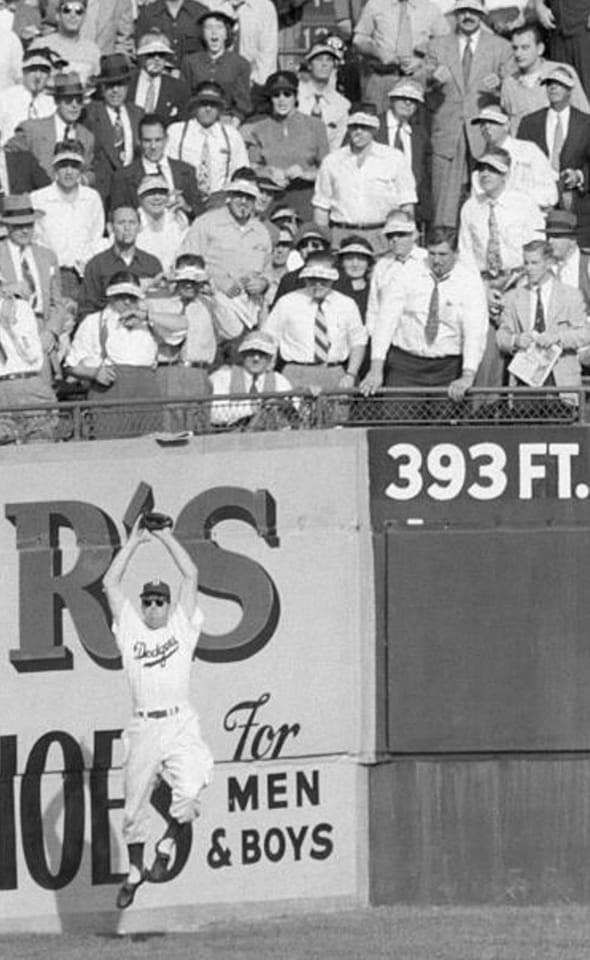

CF: Duke Snider

RF: Carl Furillo

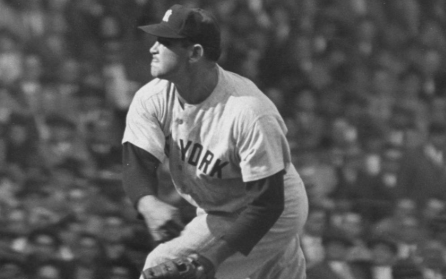

SP: Don Newcombe

SP: Carl Erskine

SP: Johnny Podres

SP: Preacher Roe

SP: Sandy Koufax

RP: Clem Labine

M: Clyde Sukeforth

Baseball is the only game you can watch on the radio. Join the community today and listen to hundreds of broadcasts from baseball’s golden age.”

Jackie Robinson Career Highlights

Jackie Robinson Career Highlights

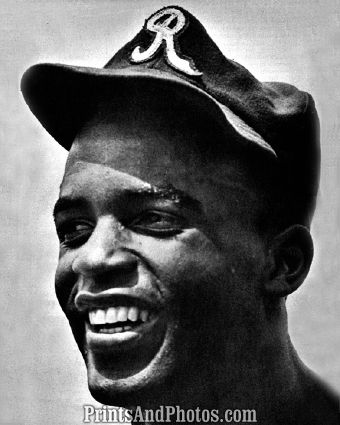

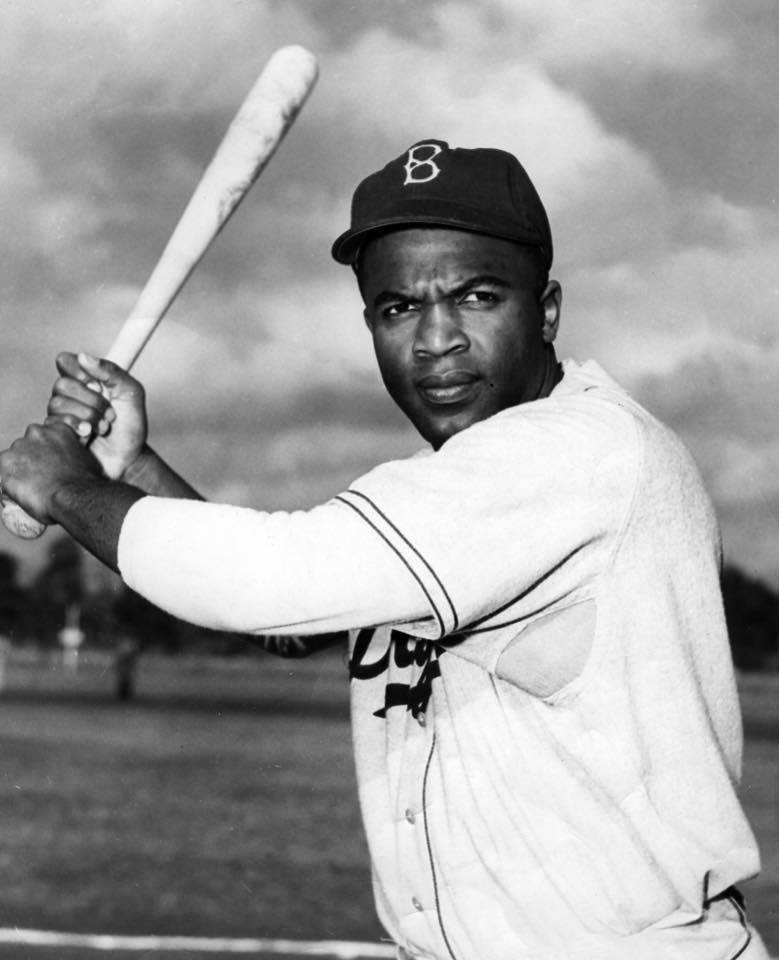

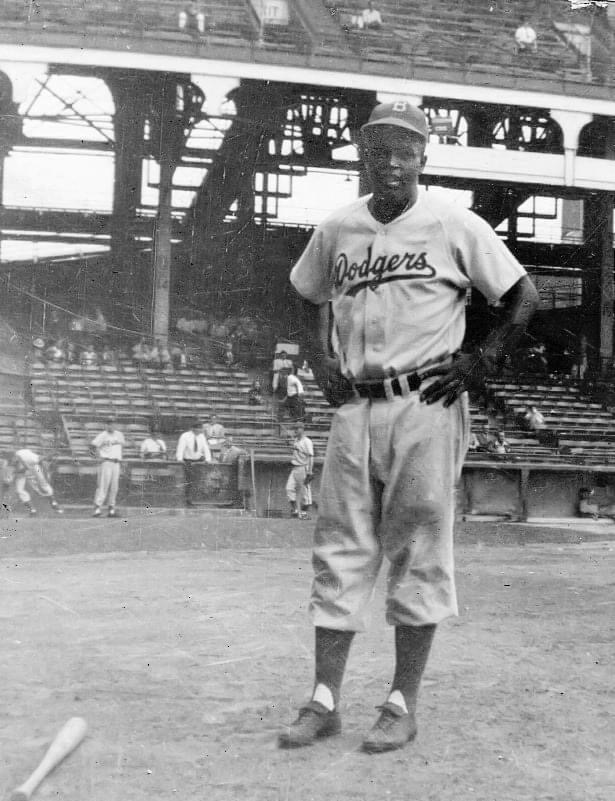

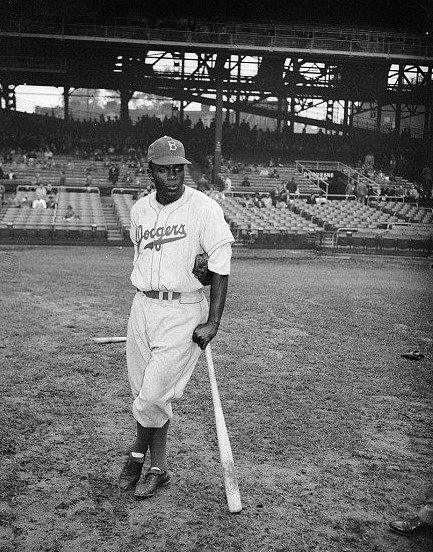

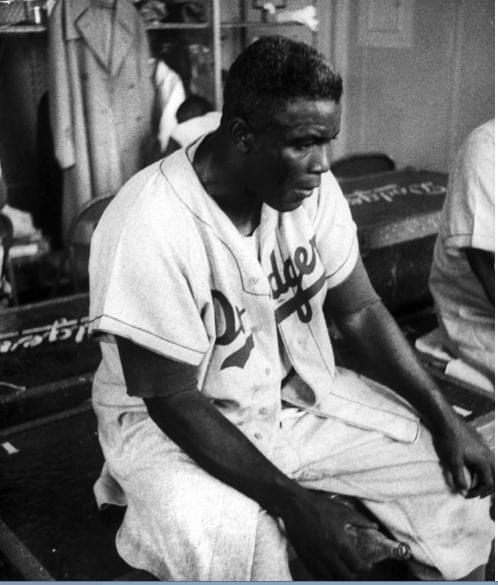

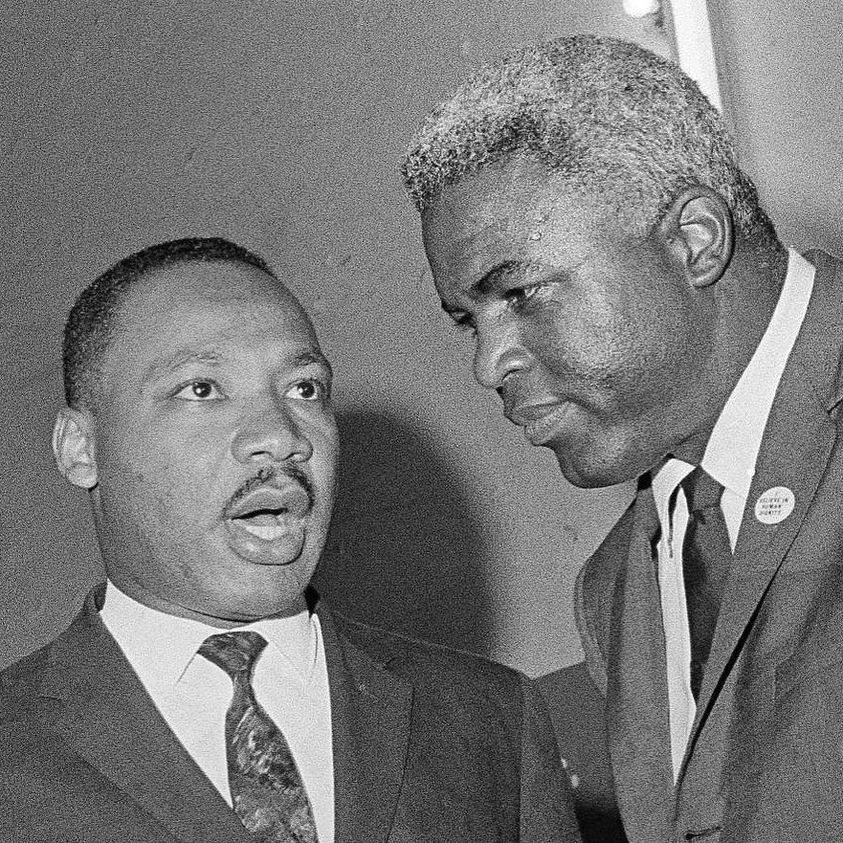

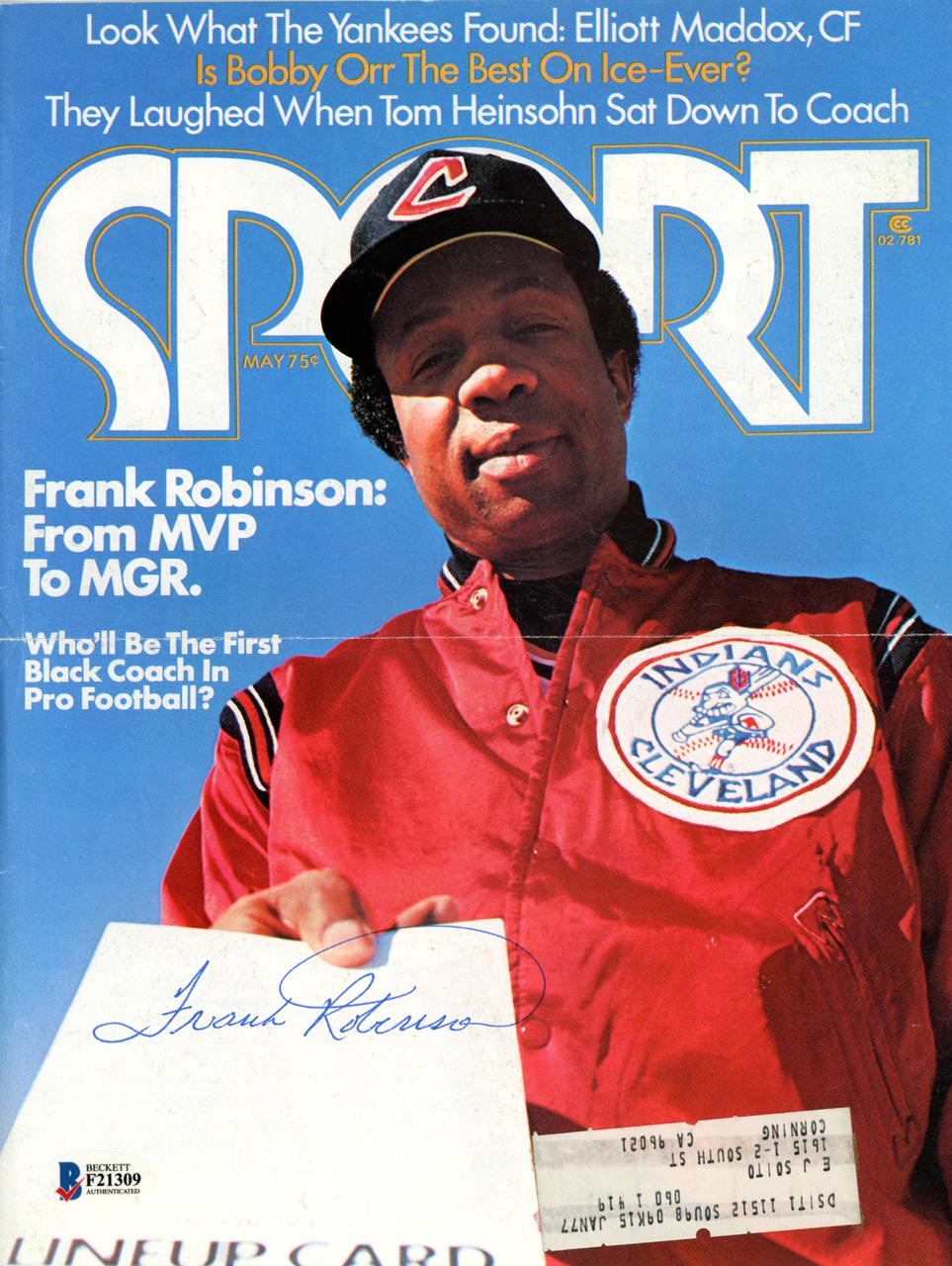

Jackie Robinson is by no means the greatest player in baseball history. He holds no cherished records in the manner of a Hank Aaron or a Joe DiMaggio, and his career numbers fall far short of the statistical milestones by which we currently measure “greatness”. But as former Negro League star Buck O’Neill once observed, Robinson may not have been the best player of his era, but he was the right player for the task history set before him. As such, Jackie Robinson is the pivotal figure in baseball’s narrative, and perhaps its greatest hero. Only a man with Robinson’s singular mix of talent, tenacity, and temperament could have taken up the lonely task of breaking baseball’s color barrier. No player before or since has had to perform under the weight of such a great burden. On one shoulder, Robinson bore the hopes and future aspirations of a people too long denied their share of the American promise; on the other, he bore the fierce scorn and violent enmity of those who preferred that baseball, and American life in general, remain a segregated affair. That he rose to the challenge and thrived under the pressure was an affirmation of America’s founding principle, the proposition that all men are indeed created equal. His triumph, coming a full seven years before Rosa Parks’ defiant “sit”, can be seen as the first great victory of the modern civil rights movement. Martin Luther King, Jr, who followed Robinson’s exploits as a teenager, hailed him as “a pilgrim that walked in the lonesome byways toward the high road of Freedom… a sit-inner before sit-ins, a freedom rider before freedom rides.” His success paved the way for a new generation of superstars – Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, and Frank Robinson, to name but a few – who would go on to revolutionize the game and help redefine American culture.

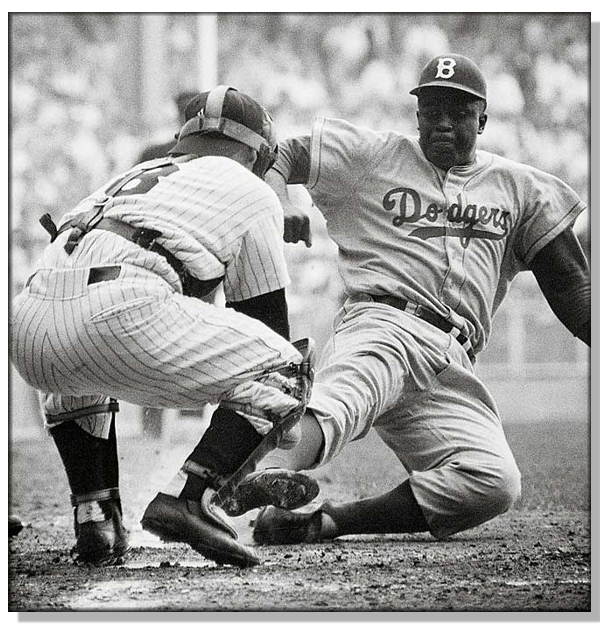

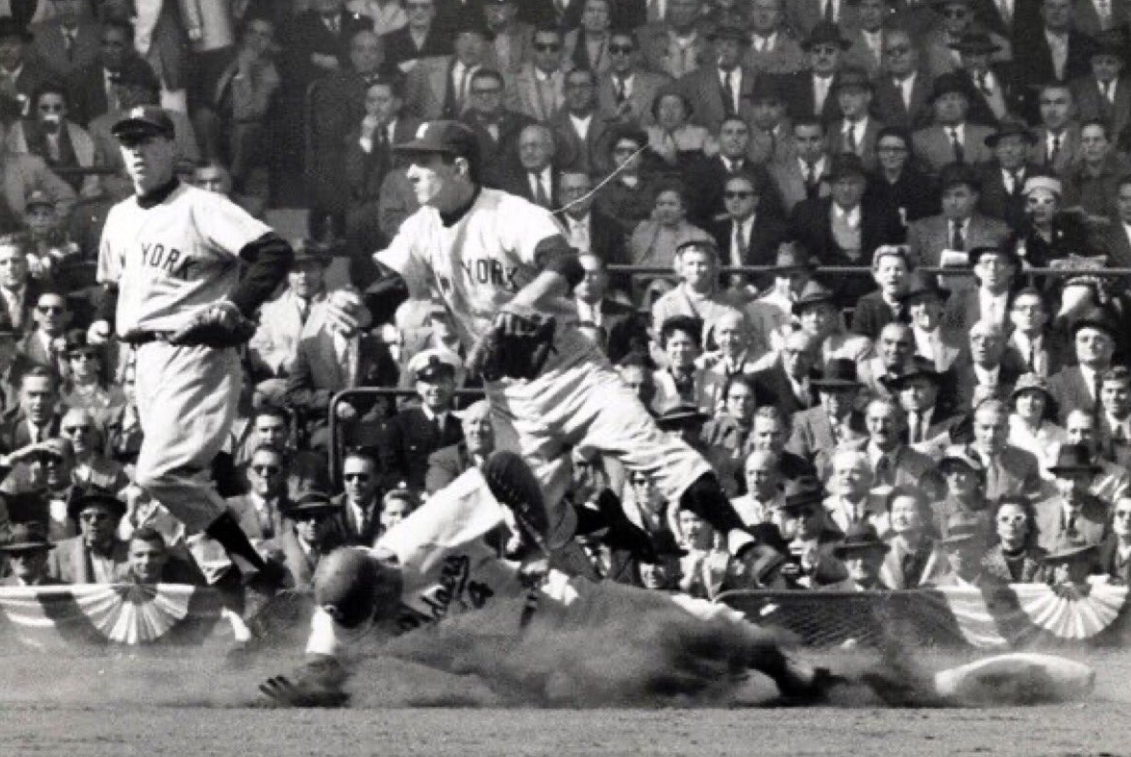

Of course, Robinson’s ascendancy to the major leagues would have amounted to little more than empty symbolism were he not also a major force on the field. When he burst onto the scene in that epochal rookie season of 1947, Robinson brought with him a new, aggressive style of play that turned the game on its ear. After a first month of starts and stops that year, Robinson shined throughout his rookie campaign, displaying an almost preternatural ability to get on base, and once there, to score (or, in many cases, steal) runs. He ended that year as the recipient of the inaugural Rookie of the Year award, an award that now bears his name. Robinson captured the MVP title a mere two years later, when he led the league in stolen bases and won the NL batting crown with a sterling .342 average. He remained a perennial MVP candidate in the years that followed, and over the course of his 10-year career his Brooklyn Dodgers reached the World Series six times. Robinson’s was a key veteran presence on the 1955 club that finally captured the Brooklyn Dodgers only world championship.

What makes Robinson’s accomplishments on the diamond all the more impressive is that, by all accounts, baseball was not even his strongest sport. Born in 1919 into a poor, single-parent family in rural Georgia, Robinson was inspired by the athletic exploits of his older siblings. His brother Mack, a silver medalist in the 1936 Olympics, encouraged Jackie to make the most of his talent for sport. After the Robinson family relocated to southern California, Jackie became a star high school athlete, earning varsity letters in basketball, football, baseball, and track. He would duplicate that feat as a standout football player at UCLA, before relocating to Hawaii to play semi-professional football with the Honolulu Bears. Robinson planned to return to the mainland to pursue his football career further, but his plans were interrupted by the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Drafted by the United States Army in 1942, Robinson was one of only a handful of black candidates to be accepted to Officers Candidate School at Fort Riley, Kansas, where he trained alongside heavyweight champion Joe Louis. Upon graduating OCS as a second lieutenant, he was transferred to Fort Hood, TX, where he soon ran afoul of the local brass for refusing to move to the back of a desegregated Army bus. Though Robinson was within his rights to do so and committed no clear offense, he was brought under court-martial. He was eventually acquitted, but the lengthy proceedings prevented his deployment abroad. Robinson received an honorable discharge in 1944, and the following year, acting on the advice of an Army buddy, tried out for and won a spot as a shortstop on the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League.

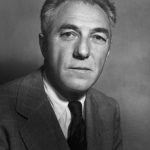

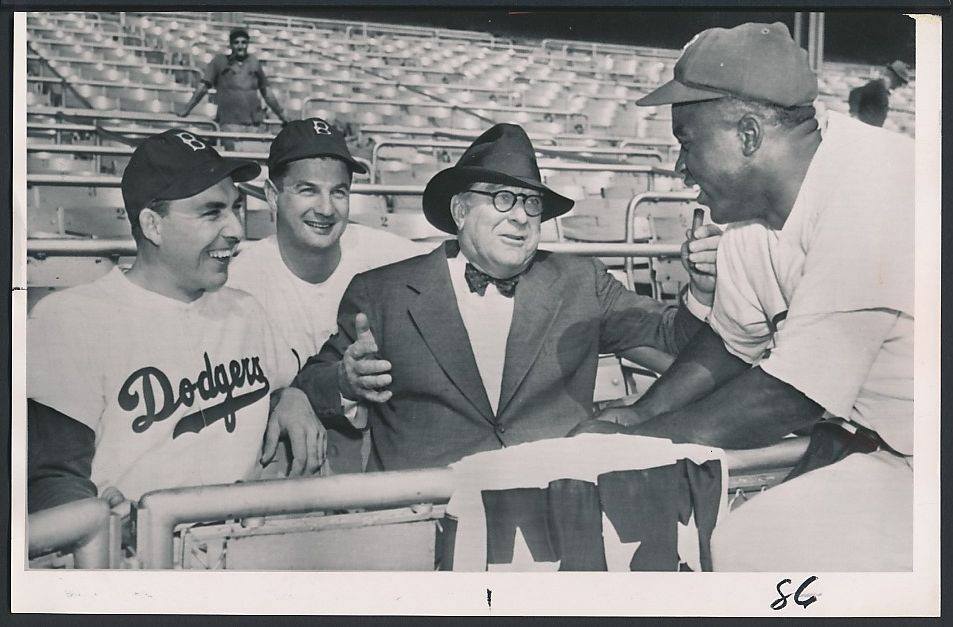

Robinson broke into the Negro Leagues shortly after Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey received the approval of Dodger management to begin scouting the Negro Leagues for “the right man”. African-Americans had been unofficially banned from the American and National Leagues since 1880, but Rickey, a shrewd baseball man, saw in the Negro Leagues a goldmine of untapped talent. He recognized, however, that the player who would be the first to break that ban needed to possess the mental restraint and resiliency to endure the racist invective and media scrutiny to which he would be subject. Robinson did enough in 47 games with the Monarchs to attract Rickey’s attention, and his .387 average, backed by his athletic pedigree, convinced Rickey to set up an interview with the young infielder. In that meeting, Rickey warned Robinson of the abuse he would face as the game’s first black player, but stipulated that if Robinson were to accept that mantle, he must not lash out or fight back against those who attacked him. Robinson accepted Rickey’s conditions, and on October 23, 1945, he signed a contract to play with the Dodgers’ AAA affiliate, the Montreal Royals.

When Robinson joined the Royals for spring training in Daytona Beach, Florida, he was barred from staying with his white teammates at the team’s hotel, and many ballparks refused to host any games in which he was scheduled to play. Though he was for the most part warmly accepted at home games in Montreal, Robinson was subject to a great deal of hostility and intimidation on the road, especially in the Jim Crow South. As much as some fans and clubs may have resented Robinson’s presence, the young star proved to be a box office smash, as attendance spiked wherever he played. Jackie proved to be a sensation between the lines as well, batting .349 with 113 runs scored over 124 games in the 1946 season.

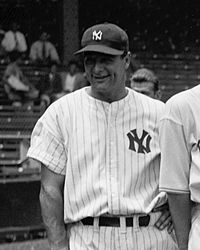

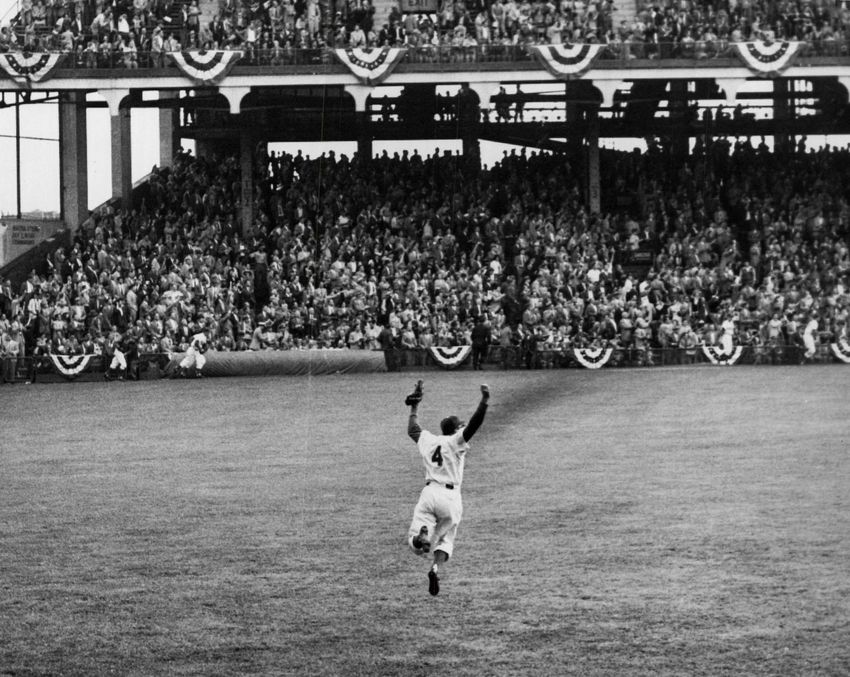

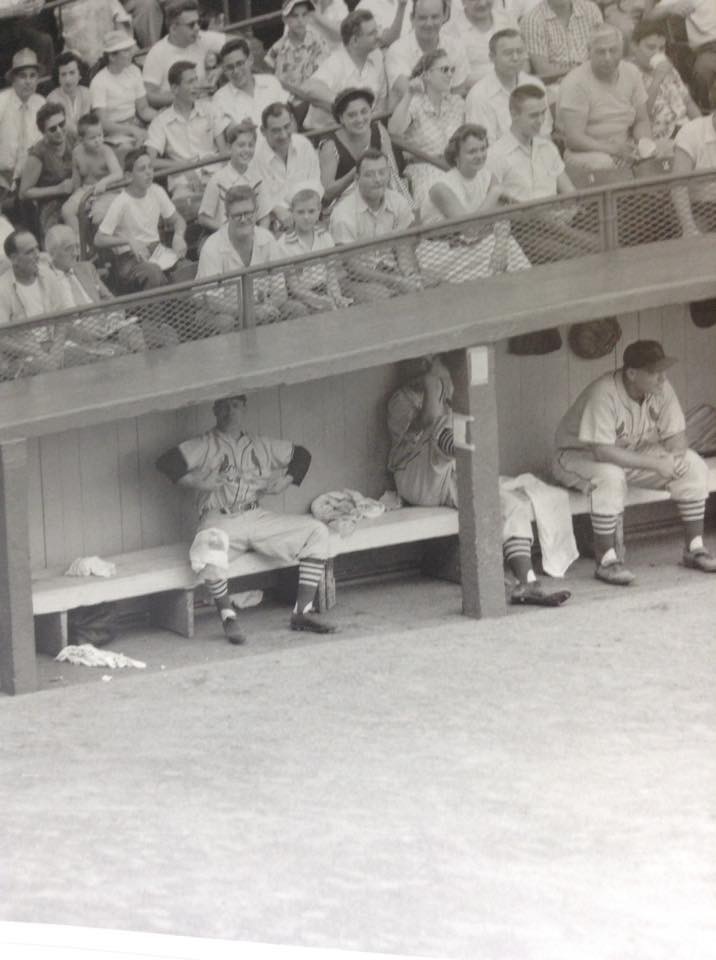

On April 10th of the following year, the Dodgers announced that they had purchased Jackie Robinson’s contract from the Montreal Royals, and that he would report immediately to start the 1947 season as the team’s first baseman. The announcement brought media and fan anticipation to a fever pitch, but the reaction of many major leaguers, including several Dodgers, was less than enthusiastic. A group of Dodger players, led by 1946 MVP runner-up Dixie Walker, threatened to strike if Robinson were allowed to start; their sentiments were echoed by a number of other players, including the entire St. Louis Cardinals team. Dodgers manager Leo Durocher quelled the dissent within his own clubhouse by threatening that any player who refused to play with Robinson would be traded, and Major League Baseball backed up his claim by announcing that any player who chose to strike as a result of Robinson’s promotion would be suspended. Amid this tense backdrop and in the eye of a media storm, Jackie Robinson made his major league debut on April 15, 1947, batting second and playing first base before a near-capacity crowd at Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field. Though he did not get a hit that day, in a sign of things to come, he was able to use his speed to reach base on a throwing error, and scored the winning run in a 5-3 Brooklyn victory over the Boston Braves.

Once the Dodgers left the relative security of Ebbets Field for their first extended road trip, Robinson was subject to blistering attacks and almost constant harassment from all sides. Death threats, by both mail and phone, became a daily nuisance, as did the vicious taunts from the grandstand. The field itself offered little sanctuary; opposing teams hurled a relentless stream of insults at Robinson, baserunners purposefully spiked him, and managers often threatened to fine pitchers who did not throw at him. Robinson, honoring the promise he made to Rickey, did not respond in kind, choosing instead to take his frustrations out on the baseball, and to wreak his own special brand of havoc on the basepaths. By May, Robinson had overcome his initial struggles, embarked on a 14-game hitting streak, and quickly established himself as a force on both sides of the diamond.

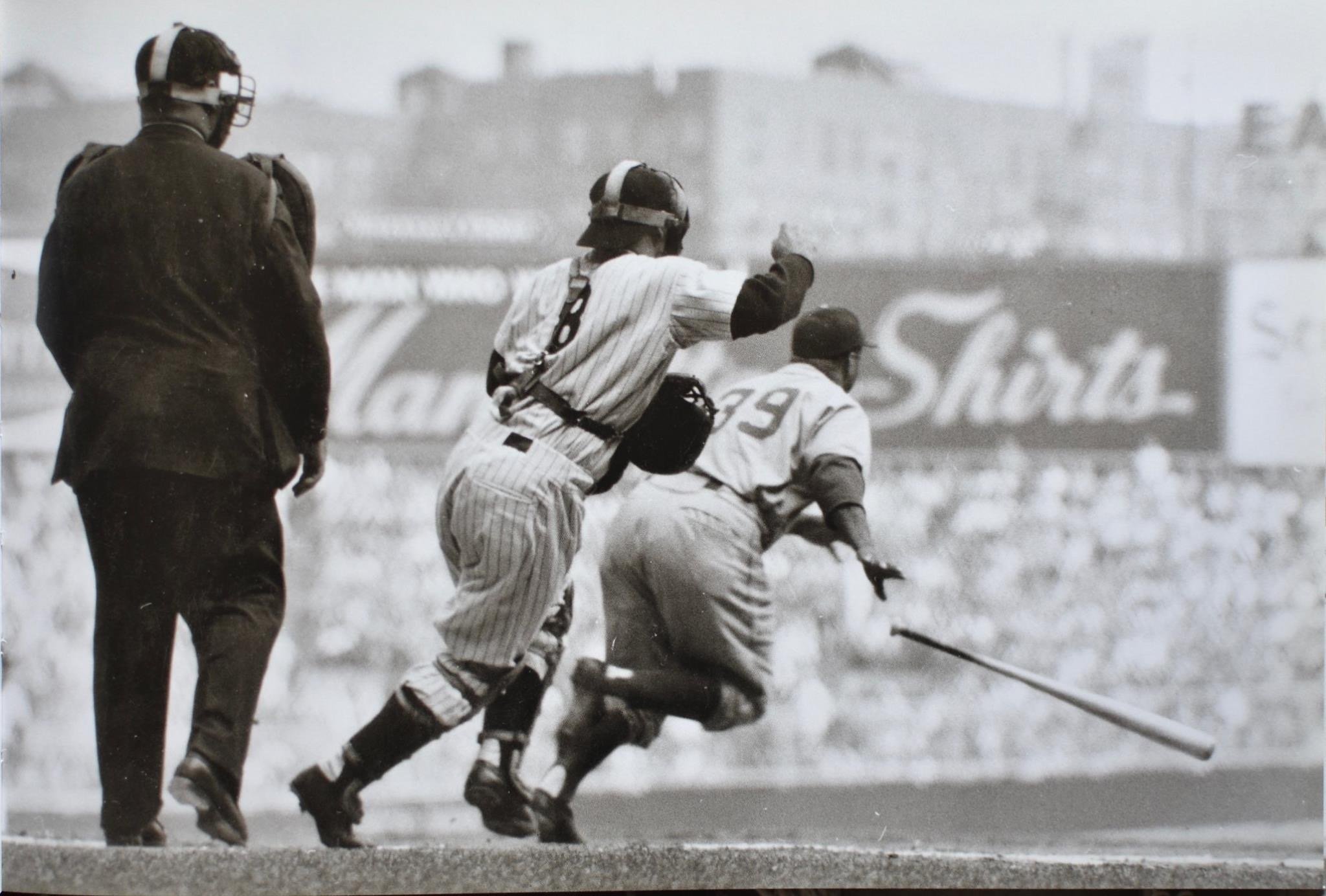

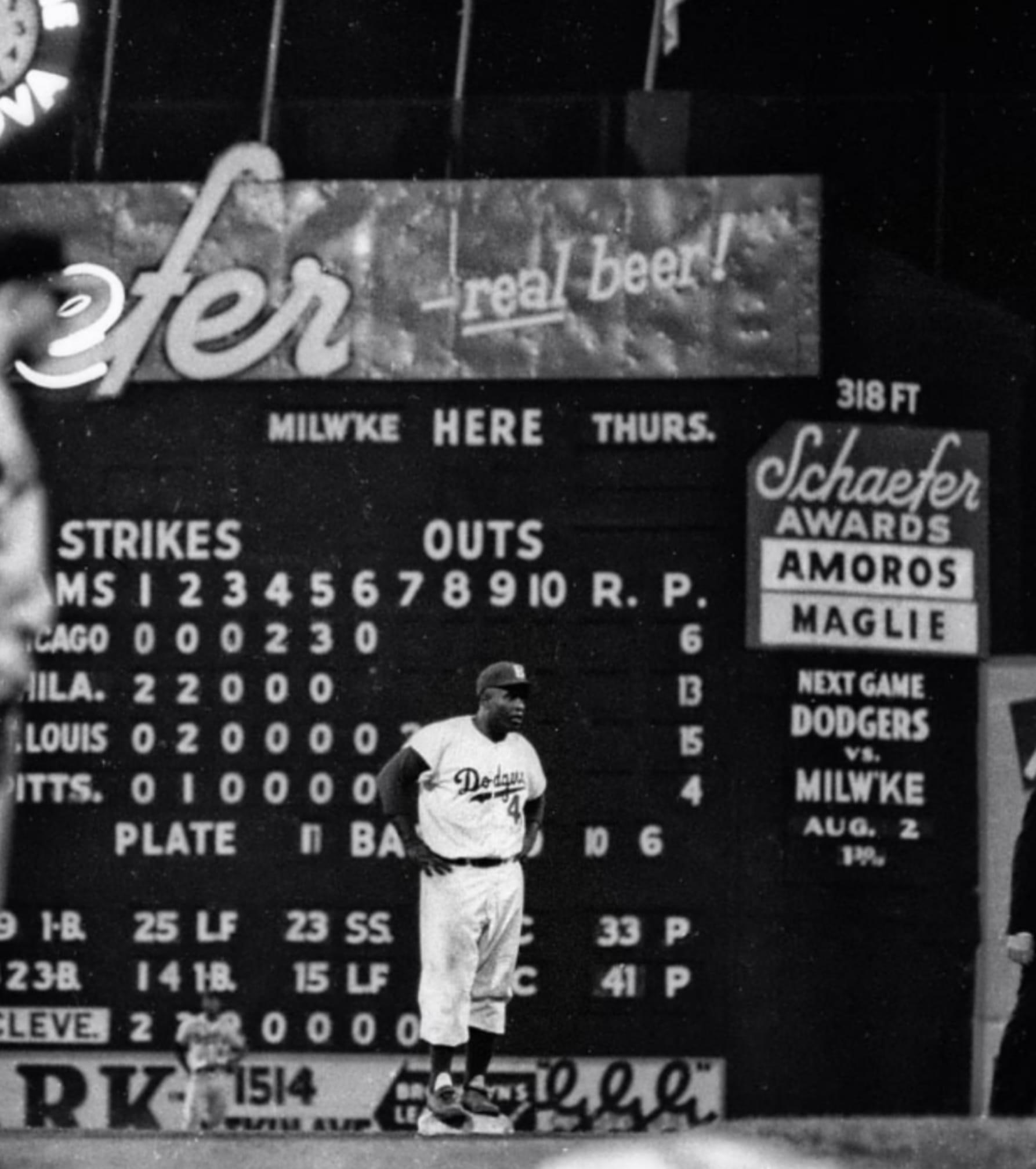

As that 1947 season progressed, the attacks on Robinson continued, but diminished in volume just as praise for his abilities (some of it grudging) gradually crescendoed. With every hit, every stolen base, Robinson was giving the lie to the notion that blacks could not compete on the same level as their white counterparts, and the example he set would have far-ranging effects on American life in the years that followed. And he received support from some influential corners. Future Hall of Famer Hank Greenberg, who had himself felt the sting of racism as the game’s first Jewish star, voiced his support of Robinson. When Greenberg’s Pittsburgh Pirates hosted the Dodgers at Forbes Field that spring, Greenberg encouraged him to “stay in there” and “keep his head up.” Dodgers captain Pee Wee Reese made a point of publicly supporting Robinson, and others in the Dodger clubhouse soon followed suit. Pitcher Ralph Branca convened a team meeting at which he urged his fellow players to get behind Robinson, pointing to him as a key to winning the pennant that year. By the end of the year, Robinson had proven Branca right: he led the league in stolen bases and scored 125 runs that year, and his daring style of play helped the Dodgers get to the World Series for only the second time in franchise history. In what would become a recurring theme over the next decade, the Dodgers fell to the archrival New York Yankees in a close seven game series, but Robinson named the Major League’s first Rookie of the Year for his accomplishments in the regular season.

The offseason that followed offered Jackie little respite, as he soon found himself in high demand as a speaker and performer, while at the same time rehabbing an ankle injury. In spite of this, Robinson turned in another fine season in 1948, batting .296 and scoring over 100 runs. His burden was lightened somewhat by the arrival of other black players, including the Cleveland Indians’ Larry Doby and Satchel Paige. In fact, Doby would steal some of the spotlight from Robinson that year, as he shined in his Indians’ World Series victory over the Boston Braves. But all eyes were once again on Jackie the following year, when he put together his finest season in the big leagues. Dissatisfied with his hitting performance up to that point, Robinson sought the advice of Hall of Famer George Sisler, who helped Jackie modify his approach at the plate. Sisler’s tutelage and Jackie’s diligence paid almost instant dividends in 1949. Robinson, raising his average from .296 to a lofty .342, captured the NL batting title that year, and once again led the league in stolen bases. With over 200 hits, 122 runs scored and 124 runs batted in, Robinson was named to his first All-Star team, and was an overwhelming choice for MVP at season’s end. His Dodgers edged out the St. Louis Cardinals for the NL pennant that year, but once again fell to the Yankees.

During the early 1950’s, Robinson improved upon his uncanny knack for getting on base and scoring runs, and was often among the league leaders in batting average, on base percentage, stolen bases, and runs scored. Shifting to second base after the departure of all-star Eddie Stanky, Robinson shined defensively, and paired with future Hall of Famer Pee Wee Reese to form one of the most effective double-play combinations in baseball history. The Dodgers, as a consequence, emerged as one of the elite teams in baseball, coming within one game of the World Series in 1951, and winning the NL pennant in four of the next five years. In the waning days of his career, as age and injury began to catch up with Robinson, his Dodgers stunned the sporting world by beating the seemingly invincible New York Yankees and capturing the 1955 World Championship. After putting in a solid, though subpar, performance in 1956, Robinson was traded to the Dodgers’ hated rival, the New York Giants. Unbeknownst to the Dodgers, however, Robinson had already accepted an executive position at the Chock Full O’ Nuts company, and had decided to retire from baseball. He was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962, his first year of eligibility. The Dodgers, who had left Brooklyn for Los Angeles following the 1957 season, retired his number 42 ten years later.

In retirement, Robinson, though struggling with injuries and the effects of diabetes, remained a vibrant force in the American Civil Rights movement, and participated in the historic March on Washington in 1963. Already one of corporate America’s first black executives, he served as an executive board member with the NAACP, and co-founded the black-owned and operated Freedom National Bank. Up until his death in 1972, he remained an outspoken opponent of racism wherever he saw it, and was a constant champion of human rights and equality. He has been posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom and the Congressional Gold Medal, the highest honors our country can bestow on a private citizen. On April 15, 1997, the fiftieth anniversary of his breaking baseball’s color barrier, Robinson’s jersey number 42 was retired by every team in Major League Baseball, an honor that had never been accorded to any figure in any professional sport.

Jackie Robinson, whom Martin Luther King described as a legend and a symbol in his own time, has become ever more so in the decades following his passing, and is viewed by many as one of the most influential figures of the twentieth century. As the first African-American star of America’s game, Robinson helped break down walls of ignorance, intolerance, and inequality that had separated blacks and whites for centuries. His courage, determination, and breathtaking ability helped usher in a new era of American history, and his struggle brought the cause of civil rights to the forefront of American society. Robinson once said that “a life is not important except in the impact it has on other lives”. When one considers the seismic social changes he helped bring about, and the trail he helped blaze for those who followed him, then by his own standards, Jackie Robinson’s was a life very well lived.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Baseball is the only game you can watch on the radio. Join the community today and listen to hundreds of broadcasts from baseball’s golden age.”

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

There are two men in baseball history that every American should learn about: Babe Ruth and Jackie Robinson. Ruth deserves to be remembered primarily for what he did between the lines, and Robinson for simply crossing the line. After Branch Rickey bravely signed him to a contract, Robinson broke the “unwritten” color barrier when he played for the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. He endured taunts, insults, threatened boycotts, death threats, isolation, and immense pressure to become the best all-around player in the National League. He won Rookie of the Year honors and the Most Valuable Player Award and led Brooklyn to six pennants in ten years.

Best Season, 1949

Jackie wasn’t a terrible second baseman. He was bounced around defensively because he was the most versatile athlete on the team. In 1949 his batting and baserunning made headlines. Robinson batted .342 (first), and finished in the top three in runs (122), hits (203), doubles, triples, RBI (124), OBP, and slugging (.528). He paced the league in steals (37) and created havoc as a baserunner. Robinson helped the Dodgers to the pennant.

Awards and Honors

1947 ML Rookie of the Year

1949 NL MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1947 World Series

1949 World Series

1952 World Series

1953 World Series

1955 World Series

1956 World Series

Description

Robinson was one of the best athletes of his era. He was far more than a great ballplayer, he was a world-class high-jumper, triple-jumper, runner, and he played college football.

Factoid

Jackie Robinson was traded to the New York Giants in December of 1956, but he retired in January and nullified the deal.

Where He Played: Everyone remembers Robinson as a second baseman, but he actually won the Rookie of the Year Award as a first baseman. But in 1948, the Dodgers dealt second baseman Eddie Stanky to the Braves, to help clear up their infield crowding. Young Gil Hodges was given the first base job, and Jackie was inserted at second base. He continued to play second until 1953, when Junior Gilliam played himself into the keystone spot. Robinson split time between left and third for the remainder of his career. By all accounts, the shifting of Robinson by the Dodgers was not because they lacked confidence in his defensive play, but rather that Jackie was the most versatile athlete on the team.

Feats: In 1947 he paved the way for African-American players to advance to Major League Baseball when he debuted as the first black player in more than 50 years… On August 29, 1948, Robinson hit for the cycle… On April 23, 1954, Jackie stole second, third, and home in the same inning.

Notes

From the May 13, 1955, New York Times: “Jackie Robinson was benched by mutual agreement with manager Smokey Alston. ‘Jack talked to me last night,’ said Alston, ‘and we both had the same idea.’ Jack, batting only .244, had suggested it might be better if he got out of the line-up for a few days, a thought that also had occurred to his manager.”

Hitting Streaks

21 games (1947)

Transactions

December 13, 1956: Traded by the Brooklyn Dodgers to the New York Giants for Dick Littlefield and $30000 cash. Jackie Robinson refused to report to his new team. Trade was voided and players returned on December 13, 1956.

All-Star Selections

1949 NL

1950 NL

1951 NL

1952 NL

1953 NL

1954 NL

Replaced

Big Ed Stevens and Stretch Schultz, who had platooned at first for the Dodgers in 1946, with little success.

Replaced By

Robinson probably could have played a few more years as an effective role player, but he retired himself as his skills started to fade. The players who benefitted from his retirement were chiefly Gino Cimoli and Charlie Neal, two young Dodgers who got regular playing time because Robinson was out of Walter Alston’s defensive rotation between third/second/first.

Best Strength as a Player

Baserunning — Robinson would have been very comfortable in the dead ball era, but as it was, he was a rare double threat in the National League at that time. He could hit the ball deep or steal bases.

Largest Weakness as a Player

Hard to find any weaknesses.

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.