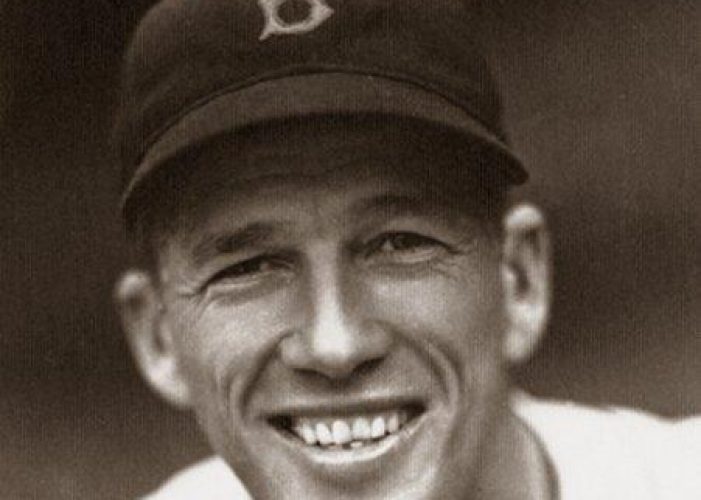

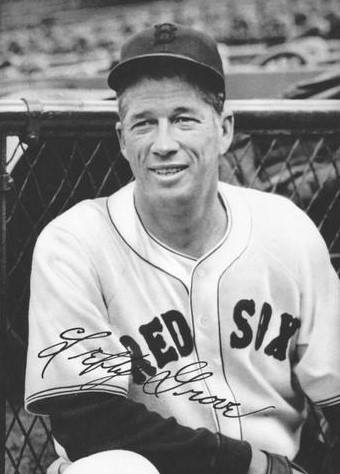

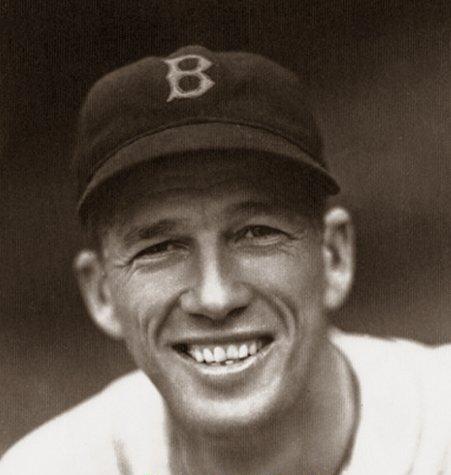

Lefty Grove

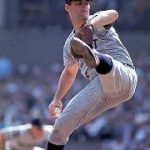

Position: Pitcher

Bats: Left • Throws: Left

6-3, 190lb (190cm, 86kg)

Born: March 6, 1900 in Lonaconing, MD us

Died: May 22, 1975 in Norwalk, OH

Buried: Frostburg Memorial Park, Frostburg, MD

High School: Central HS (Lonaconing, MD)

Debut: April 14, 1925

Last Game: September 28, 1941

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1947. (Voted by BBWAA on 123/161 ballots)

View Lefty Grove’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Rookie Status: Exceeded rookie limits during 1925 season

Full Name: Robert Moses Grove

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

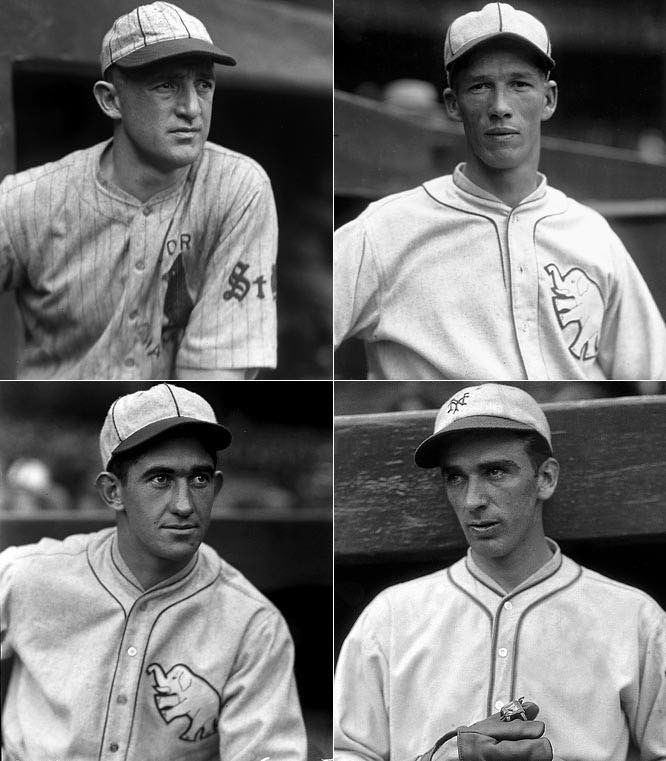

Nine Other Players Who Debuted in 1925

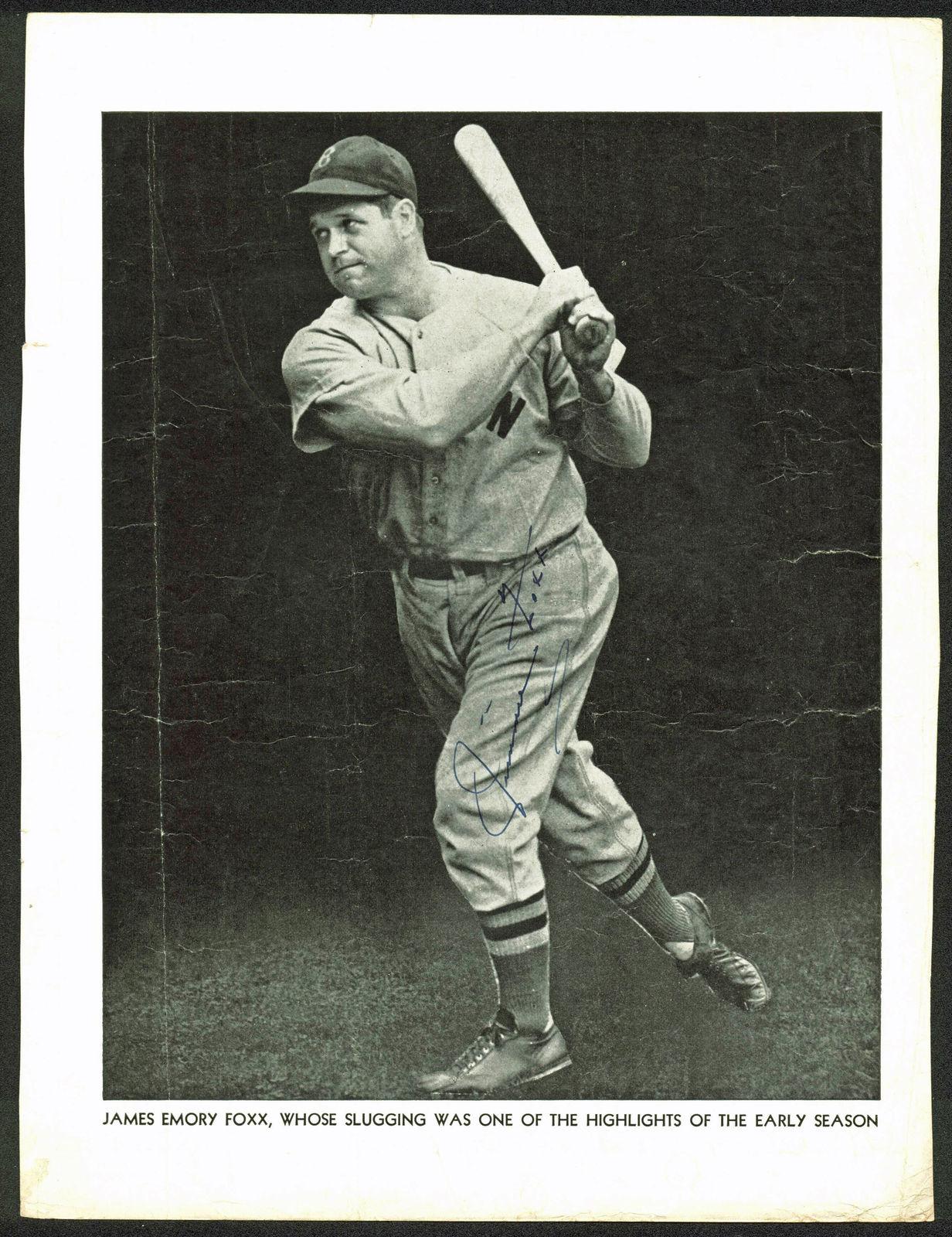

Jimmie Foxx

Mickey Cochrane

Lefty Grove

Buddy Myer

Leo Durocher

Billy Rogell

Freddie Fitzsimmons

Mule Haas

Chuck Dressen

The Lefty Grove Teammate Team

C: Mickey Cochrane

1B: Jimmie Foxx

2B: Bobby Doerr

3B: Jimmie Dykes

SS: Joe Cronin

LF: Ted Williams

CF: Ty Cobb

RF: Al Simmons

SP: Eddie Rommel

SP: Rube Walberg

SP: George Earnshaw

SP: Wes Ferrell

SP: Jim Bagby Jr.

RP: Jack Quinn

M: Connie Mack

Notable Events and Chronology for Lefty Grove Career

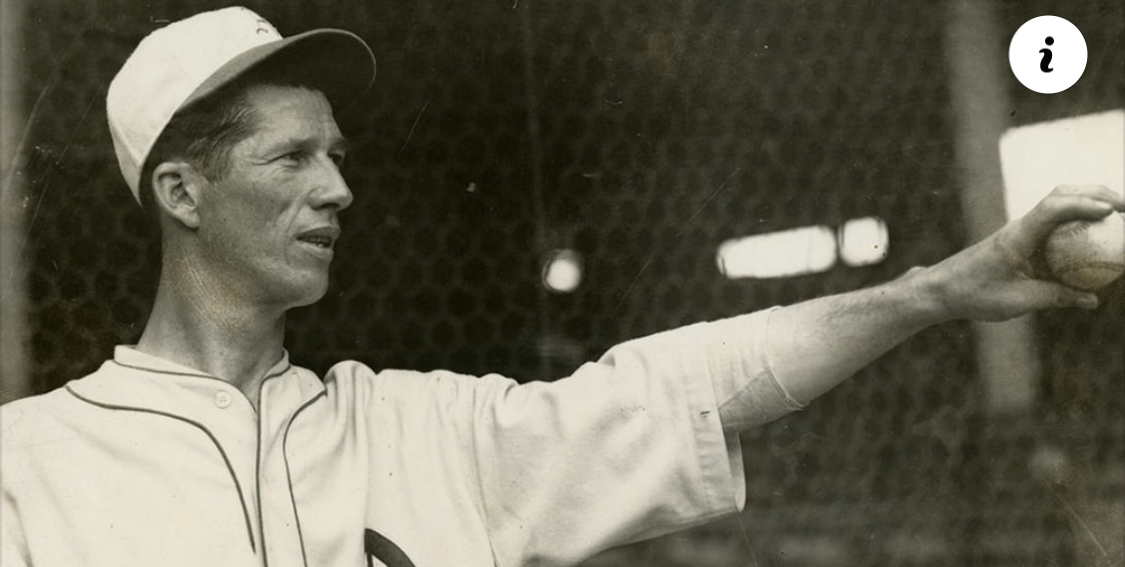

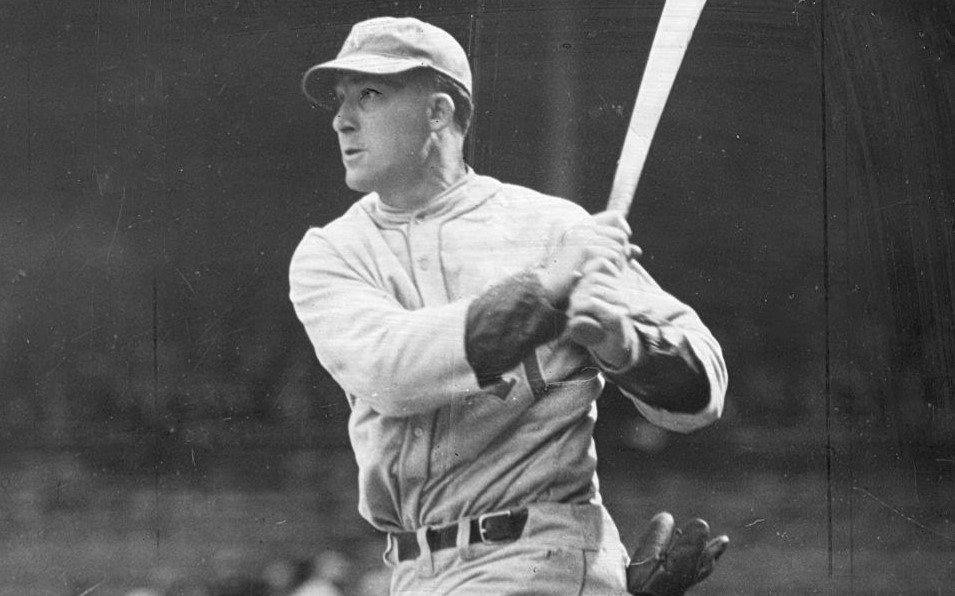

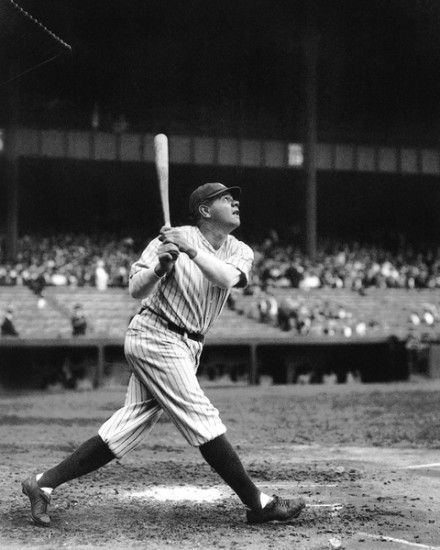

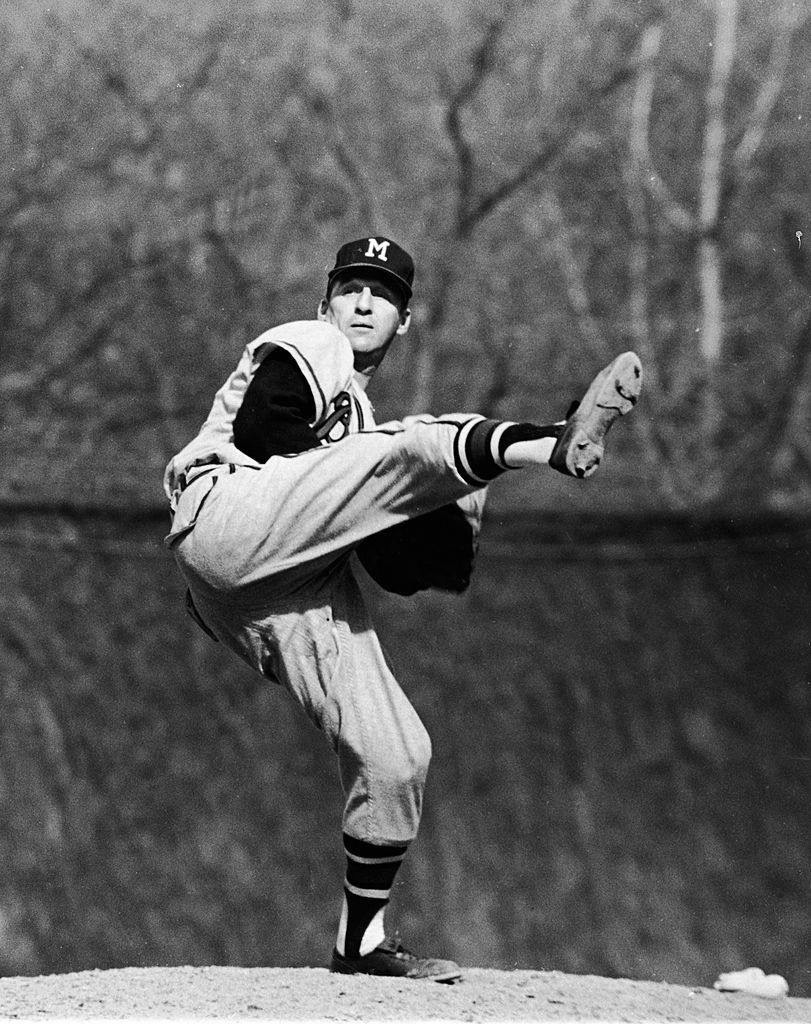

Considered by many baseball historians to be the greatest left-handed pitcher in the history of the game, Lefty Grove dominated his era the way few men have. Excelling during the 1920s and 1930s, a period is known for its offensive productivity, Grove won more than two-thirds of his lifetime decisions, annually led his league in both earned run average and strikeouts, and posted the second-best adjusted ERA of all time (behind only Pedro Martinez). Armed with a blazing fastball and a fiery temperament to match, the tall, lanky lefthander accomplished all he did despite making his first major league appearance at 25 years of age.

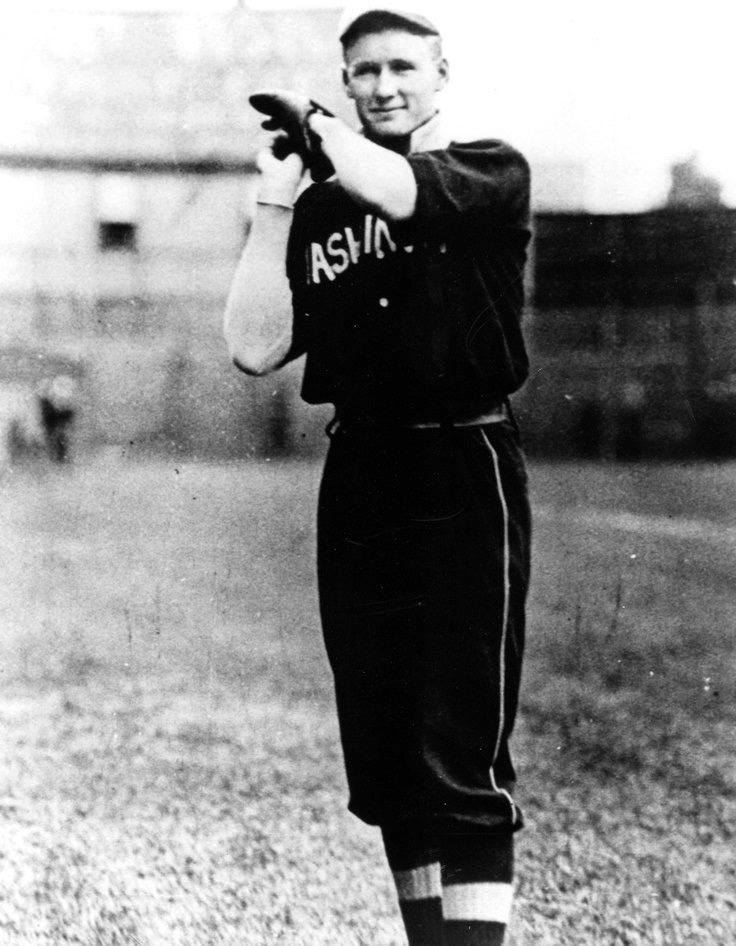

Born in Lonaconing, Maryland on March 6, 1900, Robert Moses Grove received little in the way of formal education while growing up in the nearby hills of Maryland and developing an early interest in baseball. While starring in sandlot ball around the Baltimore area during the second decade of the 20th century, Grove attracted the attention of Jack Dunn, the owner of the minor-league Baltimore Orioles, and the man who had discovered Babe Ruth just a few years earlier. Dunn signed the 6’3″, 190-pound Grove to his first professional contract, and the lefthander made his debut with the Orioles in 1920, posting a record of 12-2 in his first year with the team. He subsequently compiled marks of 25-10, 18-8, 27-10, and 27-6 over the course of the next four seasons, leading the International League in strikeouts each year, while also topping the circuit in walks in three of the four years. Grove’s performance exceeded that of every other pitcher in the league to such an extent in 1923 that his 330 strikeouts almost doubled the total compiled by league runner-up Jack Wisner, who fanned only 167 batters.

Ordinarily, Grove’s dominating performance at the minor league level would have earned him a trip to the majors after only one or two seasons. However, Baltimore owner Jack Dunn, who ran an independent operation with no major-league affiliation, repeatedly turned down offers for Grove until Philadelphia A’s owner and manager Connie Mack finally convinced him to part with his star pitcher by offering him $100,500 for the lefthander’s services. The exorbitant fee was the highest amount ever paid for a player at the time.

After making his debut with the A’s on April 14, 1925, Grove battled injuries and a lack of control as a rookie, compiling a record of only 10-12, an ERA of 4.75, and a league-leading 131 bases on balls, despite also topping the circuit in strikeouts for the first of a record seven straight times. Grove’s sub-.500 mark turned out to be the only one of his career. Although he continued to struggle somewhat with his control during his sophomore campaign of 1926, placing among the league leaders with 101 walks, Grove began to right himself, posting a record of 13-13, leading all American League hurlers with a 2.51 ERA, completing 20 of his 33 starts, and finishing among the league leaders with 258 innings pitched. He evolved into one of the league’s best pitchers the following year, winning 20 games for the first of seven consecutive times while leading the league in strikeouts for the third straight season.

The A’s became a contending team in 1928, finishing a close second to the Yankees in the race for the A.L. pennant, and Grove was at the core of their success. He finished 24-8, to lead the league in wins for the first of four times. Grove also placed among the league leaders with a 2.58 ERA, 24 complete games, and 262 innings pitched while walking only 64 batters and topping the circuit with 183 strikeouts.

Philadelphia captured the pennant in each of the next three seasons, also winning the World Series in both 1929 and 1930. Grove was at his very best throughout that period, posting records of 20-6, 28-5, and 31-4, leading the league in earned run average and strikeouts all three years, and topping the circuit in complete games, shutouts, and saves once each. He captured league MVP honors in 1931 when he won the pitcher’s triple crown for the second consecutive season. In addition to finishing 31-4, Grove led the league with a 2.06 ERA, 175 strikeouts, 27 complete games, and four shutouts. His 2.06 earned run average was more than two runs per-game lower than the league average. Although the A’s failed to win the A.L. pennant in either of the next two seasons, Grove continued to excel, combining for another 49 victories to complete a six-year stretch during which he posted an amazing record of 152-41.

Easily baseball’s most dominant pitcher during that six-year period, Grove thoroughly intimidated opposing batters with his lengthy delivery and a blazing fastball. Hall of Fame shortstop Joe Cronin later played with Grove as a member of the Boston Red Sox. However, he served as a shortstop for the Washington Senators during Grove’s peak years in Philadelphia. Cronin later said, “Just to see that big guy glaring down at you from the mound was enough to frighten the daylights out of you.”

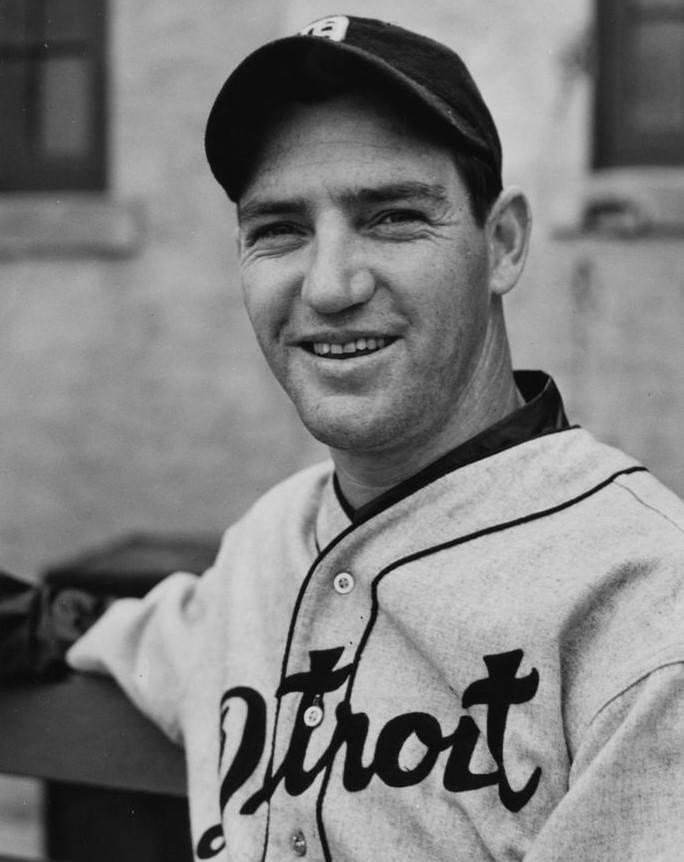

Detroit Tiger Hall of Fame second baseman Charlie Gehringer noted, “His (Grove’s) fastball was so fast that by the time you’d made up your mind whether it would be a strike or not, it just wasn’t there anymore.”

Mickey Cochrane, who played against Bob Feller when the Cleveland Indian fireballer entered the league a few year later, was the A’s regular catcher during Grove’s time with the team. Cochrane later suggested, “Feller never saw the day when he could throw as fast as Grove. Lefty was bigger, more powerful, and had a smoother delivery.”

Despite the incredible amount of success Grove experienced in Philadelphia, he frequently tested the patience of his manager and teammates with his fiery temperament and fierce competitive spirit. Known to shred uniforms, kick buckets, and rip apart lockers after a loss, Grove absolutely hated to lose, and he didn’t hesitate to blame his teammates if he felt they cost him a game. While going for an A.L. record-breaking 17th

consecutive victory in 1931, Grove became infuriated when a substitute outfielder allowed the opposing team to score the winning run by misjudging a routine line drive. The lefthander spent the next several years blaming starting leftfielder Al Simmons for taking the day off to visit a doctor.

Grove’s lack of control on the mound during the early stages of his career also exasperated manager Connie Mack from time to time. Mack later explained, “Grove was a thrower until after we sold him to Boston and he hurt his arm. Then he learned to pitch.”

As well as Grove pitched for Mack, dwindling attendance forced the A’s owner and manager to trade his star hurler to the Boston Red Sox for two ordinary players and $125,000 on December 12, 1933. An arm injury limited Grove to 12 starts and an 8-8 record in his first year in Boston. The ailment also greatly reduced the velocity on Grove’s fastball throughout the remainder of his career. Nevertheless, the tall lefthander bounced back the following season to compile a record of 20-12, hurl 23 complete games, and lead the league with a 2.70 ERA. Pitching more craftily than ever before, Grove learned to depend less on an overpowering fastball, and much more on guile. He continued to employ that philosophy the remainder of his career, excelling in each of his next four years with the Red Sox. Grove compiled an overall record of 63-29 for Boston between 1936 and 1939, winning the final two of his major-league record nine ERA titles. He spent two more years in Boston, retiring from the game at the conclusion of the 1941 campaign with a career record of 300 wins and only 141 losses, for an exceptional .680 winning percentage. Pitching exclusively during an outstanding hitter’s era, Grove also posted a career ERA of 3.06, completed 298 of his 457 starts, and threw 35 shutouts. In addition to leading the league in earned run average nine times and strikeouts on seven separate occasions, Grove topped the circuit in wins four times, winning percentage five times, and complete games and shutouts three times each. He surpassed 20 victories a total of eight times, compiled an ERA below 3.00 on nine separate occasions, and also completed in excess of 20 games nine times. Grove appeared in six of the first seven All-Star Games, and he excelled during the postseason, compiling a record of 4-2 and a 1.75 ERA in the three World Series in which he appeared.

After retiring from baseball, Grove returned to his home town of Lonaconing, Maryland, where he became a friendly townsman who learned to control his once-fierce temper. After being elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1947, Grove eventually settled in Norwalk, Ohio, where he lived peacefully until May 22, 1975, when he passed away at the age of 75.

Although many current baseball fans might tend to overlook Lefty Grove when they begin naming the greatest pitchers in the history of the game, the men who saw the big lefthander on the mound realized how great he truly was. Despite occasionally losing patience with the ace of his team’s pitching staff, Connie Mack stated in 1931, “All things considered, Grove is the best lefthander that ever walked on a pitcher’s slab. He surpasses everybody I have ever seen. He has more speed than any other lefthander in the game.”

Mack added, “(Rube) Waddell was a remarkable pitcher. We all know that. But he wasn’t dependable. He didn’t take care of himself. Grove isn’t that way. Lefty’s always in condition. He’s as dependable as the tides…He’s faster than Waddell too.”

Meanwhile, noted author and baseball historian Bill James suggests, “What argument, if any, could be presented against the proposition that Lefty Grove was the greatest pitcher who ever lived?”

Quotes about Grove:

In a 1941 interview with The Washington Post, Charlie Gehringer was asked if he thought Bob Feller had supplanted Walter Johnson as the premier fireballer of all-time. “Leave me out of this Johnson-Feller thing,” replied an incredulous Gehringer. “I can tell you one thing: Feller has never shown me a fastball like Lefty Grove . . . you were up there swinging at an aspirin tablet.” Gehringer, a career .320 hitter and one of the toughest strikeouts of all-time (one K per 23.8 at-bats), was an expert on the subject, having faced Grove more often than anyone else. In 201 at-bats versus the superlative southpaw, “The Mechanical Man” – who hit .317 when facing left-handed starters not named Grove – posted a paltry .244/.280/.348 slash-line while fanning 20 times (once every 10 at-bats). Conversely, against a young Bob Feller, Gehringer struck out only six times in 84 plate appearances, while compiling a terrific .373 on-base percentage.

On March 4, 1938 – two days before Lefty’s 38th birthday – longtime umpire “Brick” Owens, in an interview with The Associated Press, lists Walter Johnson, Grove, and “young Bobby Feller” as “the three fastest pitchers in history”; Owens adds that Johnson had the most deceptive delivery he’d ever seen, though he couldn’t match the latter two in pure velocity. Several years earlier, “The Big Train” himself cited Grove as the fastest pitcher since Smoky Joe Wood. Johnson’s only knock on Lefty: “His fastball comes at you straight as a string.” Despite the purported lack of movement, Grove relied upon, in his words, “nuthin’ but fastballs” early in his pro career, though he occasionally threw a change-of-pace and what would eventually be known as a slider (Lefty called it a “sailor”).

Grove, who found himself stuck in the minors due to Orioles’ owner Jack Dunn’s reluctance to sell his stars, didn’t make the big leagues until age 25. Over five seasons (1920-24) in the International League, Lefty won 111 games while striking out a minor league record 1,108 batsmen. (During an exhibition series versus a team of big leaguers, Grove fanned Babe Ruth nine times in eleven at-bats.) Upon joining the Philadelphia A’s in 1925, the erratic hurler struggled to the tune of a 4.75 ERA, though his 116 Ks (and 131 walks) paced the American League. Much like a young Koufax some three decades later, Lefty’s command was a work in progress. “Catching him was like catching bullets from a rifleman,” declared Mickey Cochrane, then in his rookie season as well. Philadelphia’s veteran backup catcher, Cy Perkins, was also impressed, calling Grove’s heater “the fastest ball in existence.”

Embarrassed by his lackluster ERA and lack of control, Grove – never one to rest on his laurels – spent the off-season honing his craft. “I’ll show ’em something next year,” he insisted. True to his word, Lefty dominated in 1926, pacing the majors with a 2.51 earned run average (his first of a record nine ERA titles) and 194 strikeouts. “Now he has wide, bending curves [and] better control . . . and he’s the speediest pitcher in baseball,” noted Yankees skipper Miller Huggins, who had called Grove a “dud” a year earlier.

The 1926 season was just the tip of the iceberg, so to speak: Grove embarked upon a seven-year run (1927-33) that saw him compile an MLB-best 2.75 ERA and average 25 wins per season while capturing two pitching Triple Crowns and an MVP title along the way. According to baseballreference.com, Grove paced American League hurlers in various positive pitching categories 93 times during the span. Given the historically high run-scoring environment, it’s easy to conclude that no pitcher in MLB history was ever more dominant than Lefty at his peak. “I’ll tell you about Grove,” rhapsodized Connie Mack. “When I sent [him] in to pitch, I could be almost positive we would win the game if we gave him a run or two; you can’t say that of many pitchers.”

The 1934 season – his first with the Red Sox – marked a turning point for Grove’s career in more ways that one. At age 34, still relying heavily on his fastball, the once inextinguishable ace felt something snap in his left elbow that spring. Though the papers called it a “sore arm,” it’s more likely that Grove tore his UCL (ulnar collateral ligament) – an injury that ended many a career in the days before Tommy John surgery. Undaunted, Lefty went about business as usual, stubbornly throwing one painful “fastball” after another. The end result: an astronomical 6.50 ERA and a long stint on the disabled list. That off-season, just as he did following his rookie campaign a decade earlier, Grove set out to reinvent himself, developing a slow curve to go along with a formidable forkball. The venerable hurler later explained: “A pitcher has time enough to get smarter after he loses his speed.”

The new approach paid immediate dividends, as Grove enjoyed his eighth 20-win season while pacing the American League in ERA (2.70) and finishing fourth with 121 Ks. Amazingly, the resilient 36-year-old wasn’t done: Lefty captured ERA crowns in three of the next four seasons (1936-39). “He has learned to think,” Connie Mack explained. “He [now] relies on his pitching brain.” Incidentally, 1936 was Bob Feller’s first year in the majors. Though only 17-years old, the sublime “schoolboy sensation” would soon unseat Grove as baseball’s preeminent strikeout artist and moundsman extraordinaire. Though that gent kneweth not of baseball, p’rhaps William Shakespeare putteth t most wondrous: “Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.”

On June 27, 1938, Grove, sporting an MLB-best 11-2 record, squared off with Feller – who at age 19 was leading the majors with 84 Ks – for the first time. Though it had the makings of an epic pitching duel, the game would turn into a lopsided affair as youth reigned supreme. Feller hurled a complete game, allowing two runs while fanning 10 hapless batsmen; conversely, Lefty looked as though he were throwing batting practice that day in Cleveland. All told, the 38-year-old was rocked for 13 hits and six runs before being mercifully removed in the seventh inning. In its coverage of the contest, The Washington Star wrote that “over 10,000 turned out to see Bobby Feller hand it to Lefty Grove.” Though Lefty would go on to capture another two ERA titles, for all intents and purposes, the baton had been passed – a new king had ascended the throne. In baseball, as in life: the beat goes on. ~ BK2

“A story has no beginning or end: arbitrarily one chooses that moment of experience from which to look back or from which to look ahead.” — Graham Greene

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Philadelphia Athletics (1925-1933)

Boston Red Sox (1934-1941)

Linked: Al Simmons did not play in left field on August 23, 1931, having gone to a doctor instead. His replacement, Jimmy Moore, drew the wrath of Grove when he misjudged a fly ball and lost the game, which would have been Grove’s AL-record 17th straight win… Connie Mack paid $100,600 to get Grove from the Baltimore Orioles of the International League in 1925, topping the record $100,000 the Yankees had paid the Red Sox for Babe Ruth… On April 14, 1925, two future Hall of Famers made their debut in the same game. Grove started the game against the Boston Red Sox, and in the eighth inning, Mickey Cochrane pinch-hit and singled. Cochrane entered the game and caught Grove… On May 30, 1925, Grove, a rookie, stopped George Sisler’s 34-game hitting streak… Ted Williams went 2-for-3 in the final game of the 1941 season to raise his average to .406, In that same game, Grove pitched for the last time, losing 7-1 to the A’s.

Best Season, 1931

Grove followed up his amazing 1930 season (28-5, 18 relief appearances, and nine saves) with an even better year. He helped the A’s to their third straight pennant, no small feat with Gehrig and Ruth’s Yankees in the same league. Grove went 31-4, with a league-best 2.06 ERA. The league ERA was 4.51. He also led in K’s, WHIP, complete games, and shutouts. He won 16 games in a row. Once again he proved valuable out of the pen, saving five games. He was honored as the league’s MVP.

Awards and Honors

1930 AL Triple Crown

1931 AL MVP

1931 AL Triple Crown

Post-Season Appearances

1929 World Series

1930 World Series

1931 World Series

Factoid

From July 25, 1930, through September 24, 1931, Lefty Grove was an incredible 46-4. According to researcher Jim Kaplan, this is the best 50-game stretch by any pitcher in baseball history.

Where He Played: Starting pitcher, and like most aces of his era, Grove served as a relief pitcher in between starts.

Feats: On July 25, 1941, Grove won his 300th — and final — game, a 10-6 victory over Cleveland.

Transactions

December 12, 1933: Traded by the Philadelphia Athletics with Max Bishop and Rube Walberg to the Boston Red Sox for Bob Kline, Rabbit Warstler, and $125,000 cash.

First Tilt by the Lake

On July 31, 1932, the Indians moved into their new ballpark, Municipal Stadium. Mel Harder and Grove tangled in a pitcher’s duel won by Lefty, 1-0, on Mickey Cochrane’s RBI single. More than 80,000 were in attendance.

Factoid

Lefty Grove was the first American League pitcher to lead the league in K’s and walks in the same season (1925).

Streak Stopper

The New York Yankees posted a somewhat unbelievable feat of playing 308 straight games without being shut out, beginning August 2, 1931. Two years and one day later, Lefty Grove stopped the streak, blanking Ruth, Gehrig, Dickey and the gang, 7-0, on August 4, 1933.

Sunday’s Best

On August 22, 1926, after three straight rainouts, Connie Mack decided that the time for Sunday baseball in Philadelphia had come. Armed with a court injunction preventing police from interfering, the A’s played the White Sox in a light rain that kept the crowd down to 10,000. Lefty Grove started and won the first Sunday game in Philadelphia, 3-2. A court later ruled that Sunday baseball was still illegal, and it wasn’t until 1934 that the law was abolished in Philadelphia.

Quotes About Grove

“All things considered, Grove is the best lefthander that ever walked on a pitcher’s slab. He surpasses everybody I have ever seen. He has more speed than any other lefthander in the game.” — Connie Mack, 1931

“Waddell was a remarkable pitcher. We all know that. But he wasn’t dependable. He didn’t take care of himself. Grove isn’t that way. Lefty’s always in condition. He’s as dependable as the tides… He’s faster than Waddell, too.” — Connie Mack, 1931

Factoid

No pitcher/batter has ever struck out as many times as Lefty Grove. Grove fanned 593 times in 1,369 official at-bats, or 43% of the time.

All-Star Selections

1933 AL

1935 AL

1936 AL

1937 AL

1938 AL

1939 AL

Replaced

Left-hander Stan Baumgartner, in the 1925 Athletics’ rotation.

Replaced By

34-year old rookie left-hander Oscar Judd, in the Red Sox’ 1942 rotation.

Best Strength as a Player

Location of his fastball.

Largest Weakness as a Player

His temper.

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.