[adrotate banner=”50″]

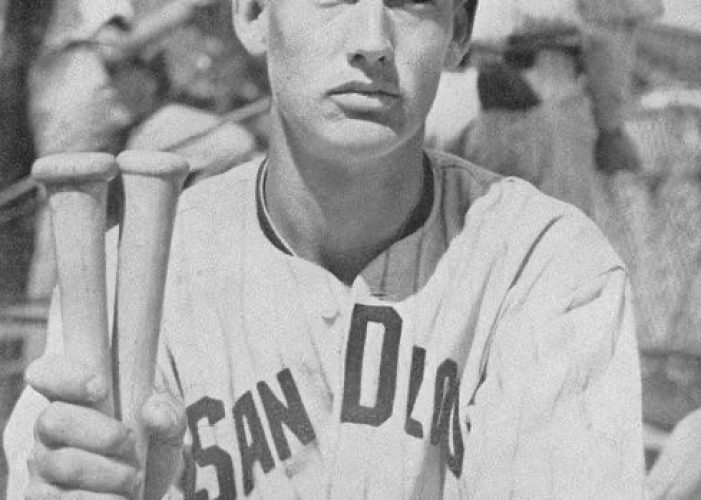

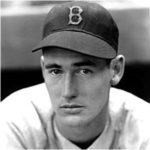

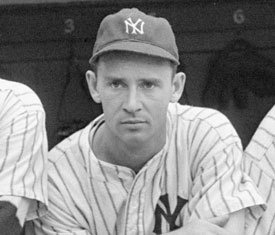

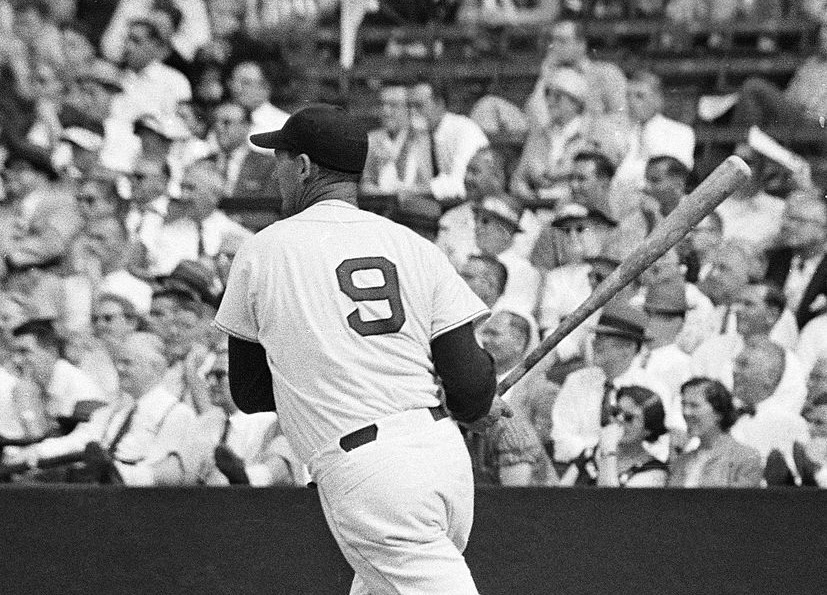

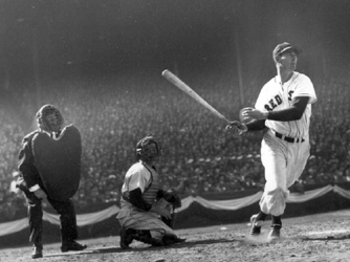

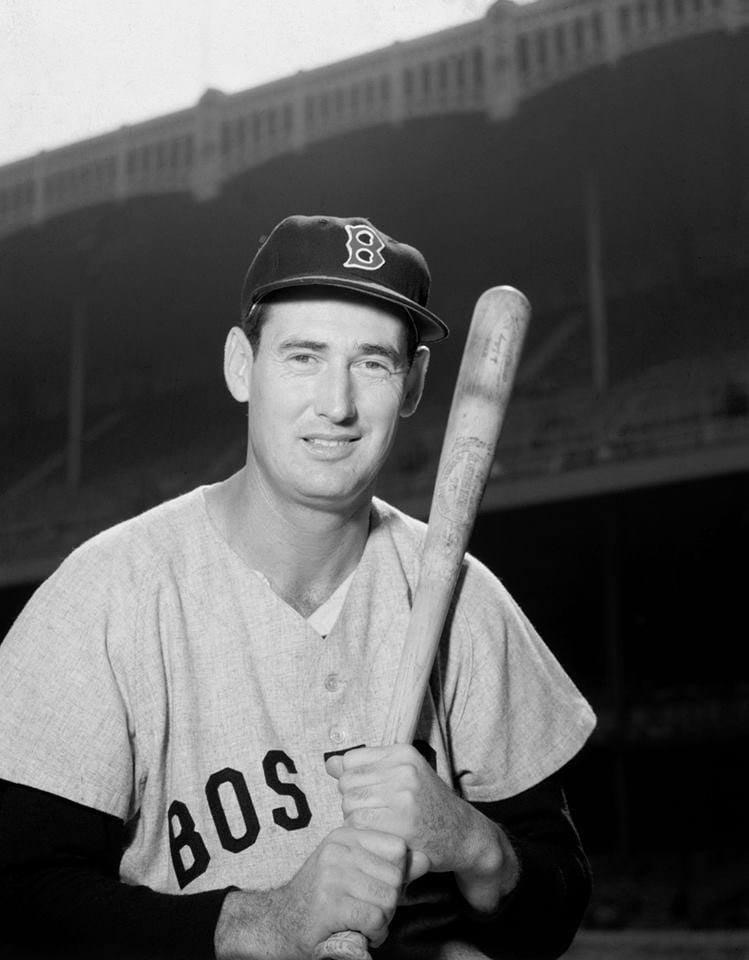

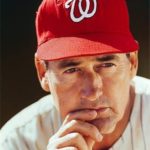

Ted Williams

Position: Leftfielder

Bats: Left • Throws: Right

6-3, 205lb (190cm, 92kg)

Born: August 30, 1918 in San Diego, CA us

Died: July 5, 2002 in Inverness, FL

Buried: Frozen

High School: Herbert Hoover HS (San Diego, CA)

Debut: April 20, 1939 (8,629th in major league history)

vs. NYY 4 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 28, 1960

vs. BAL 3 AB, 1 H, 1 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1966. (Voted by BBWAA on 282/302 ballots)

View Ted Williams’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Theodore Samuel Williams

Nicknames: The Kid, Teddy Ballgame, Splendid Splinter or Thumper

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1939

Ted Williams

Mickey Vernon

Bob Elliott

Bob Kennedy

Early Wynn

Hal Newhouser

Dizzy Trout

Fred Hutchinson

Johnny Hopp

The Ted Williams Teammate Team

C: Sammy White

1B: Jimmie Foxx

2B: Bobby Doerr

3B: Joe Cronin

SS: Vern Stephens

LF: Carl Yastrzemski

CF: Dom DiMaggio

RF: Jackie Jensen

SP: Mel Parnell

SP: Lefty Grove

SP: Tex Hughson

SP: Joe Dobson

RP: Ellis Kinder

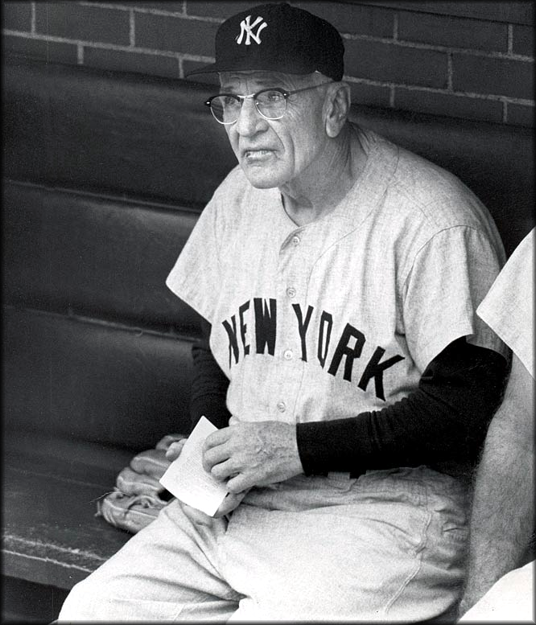

M: Joe McCarthy

Vintage Baseball HOT ON EBAY

Card Collections ENDING SOON ON EBAY

MOST WANTED ROOKIE CARDS

VINTAGE SPORTS TICKETS

Baseball Hall of Famers

Notable Events and Chronology for Ted Williams Career

Biography

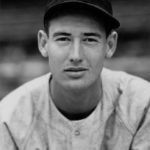

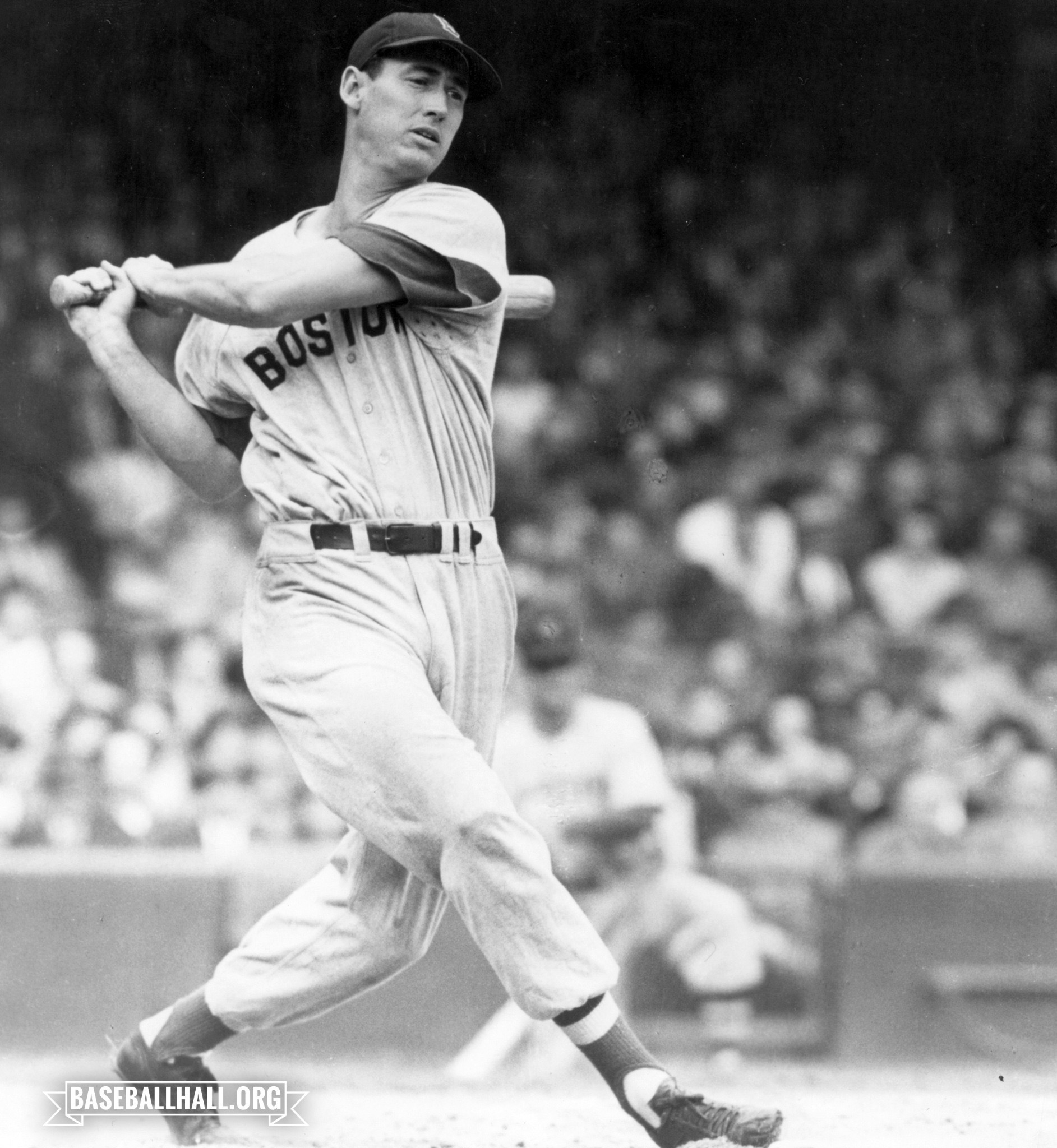

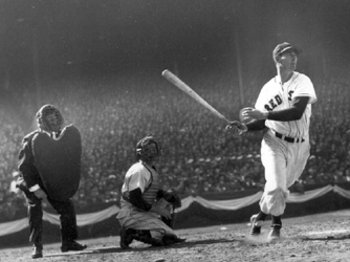

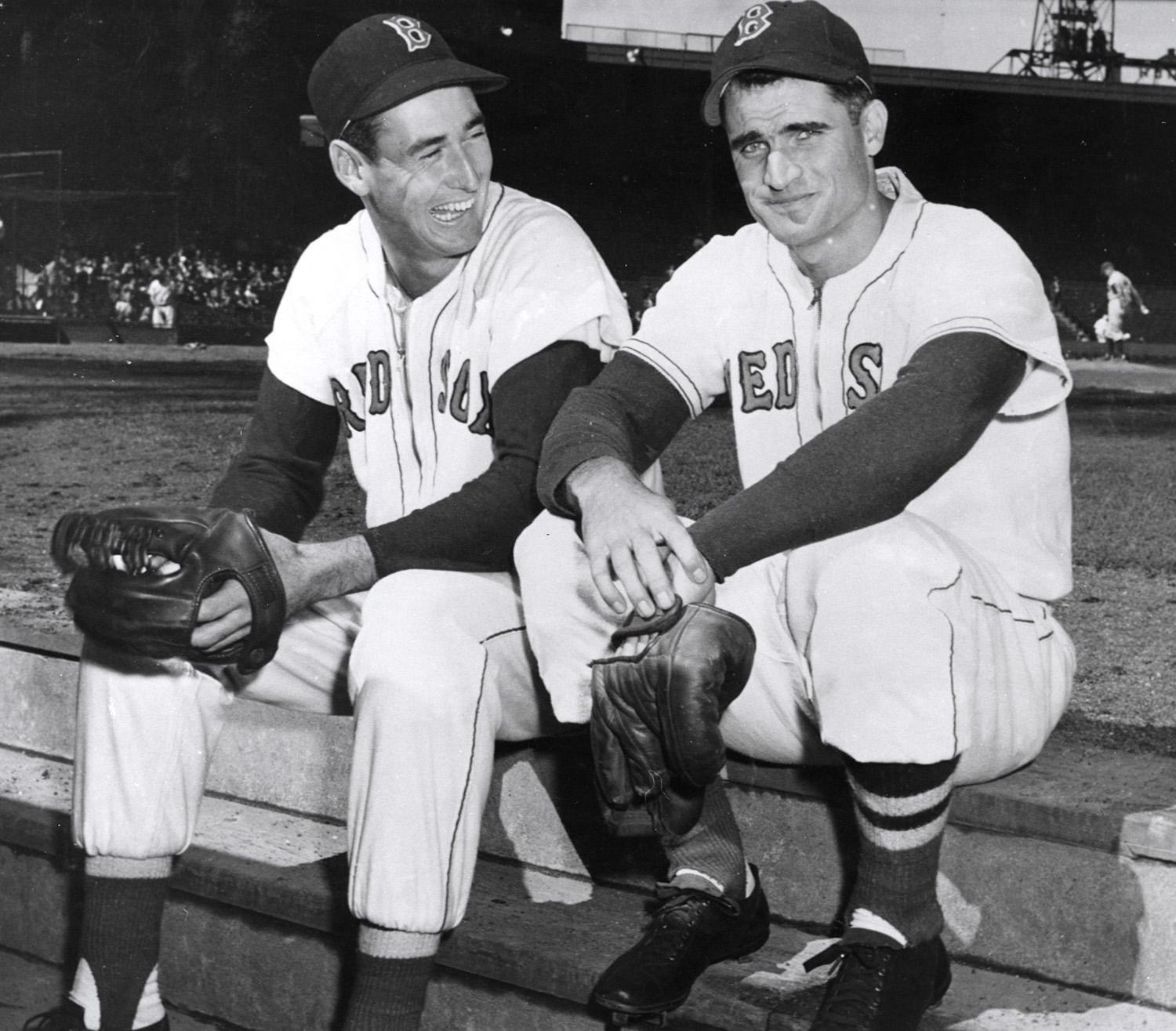

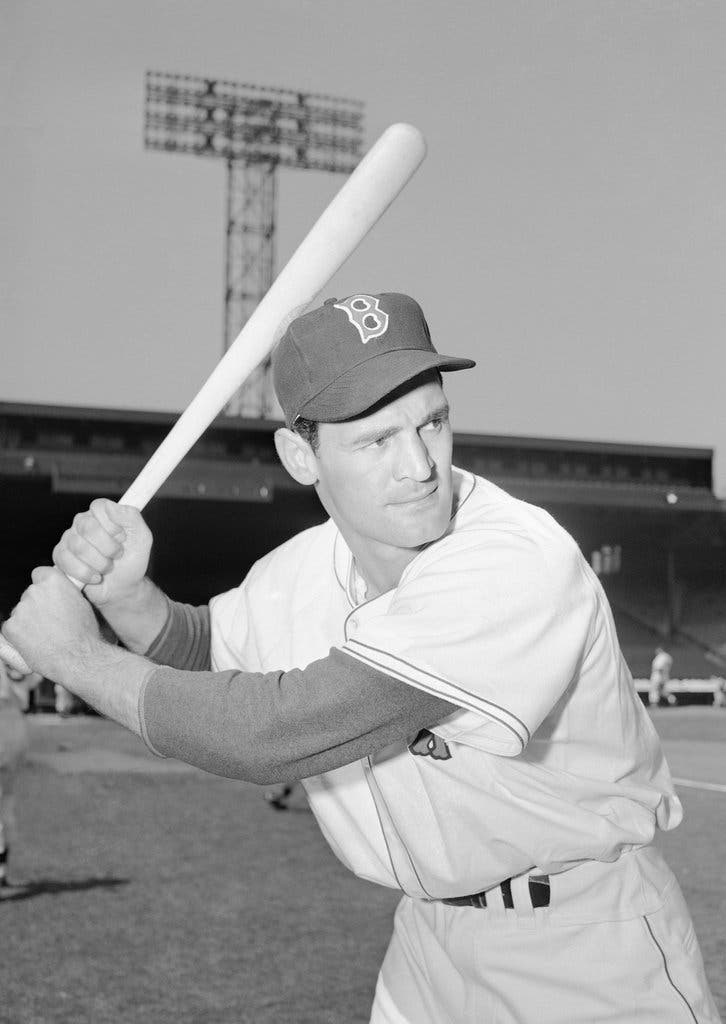

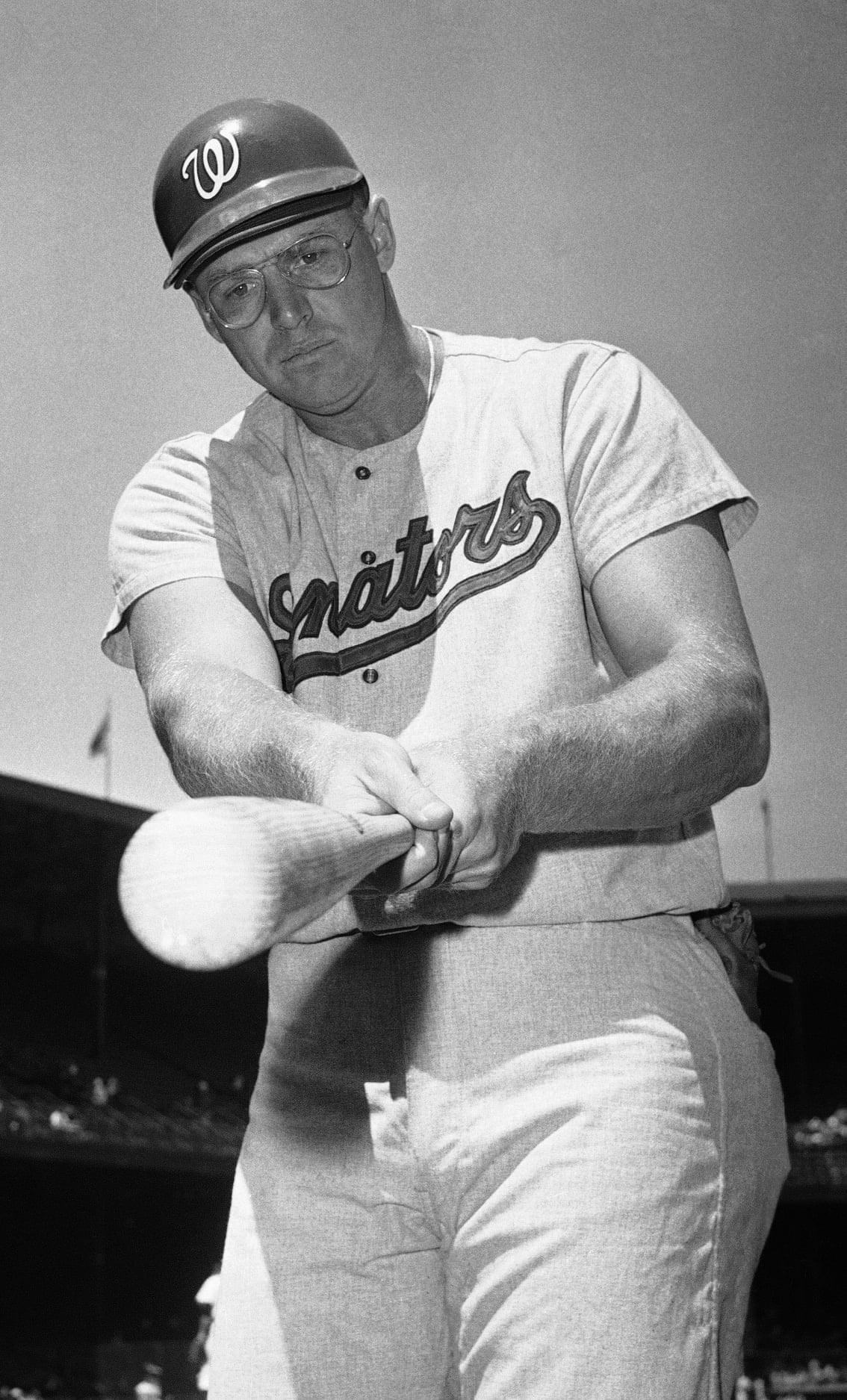

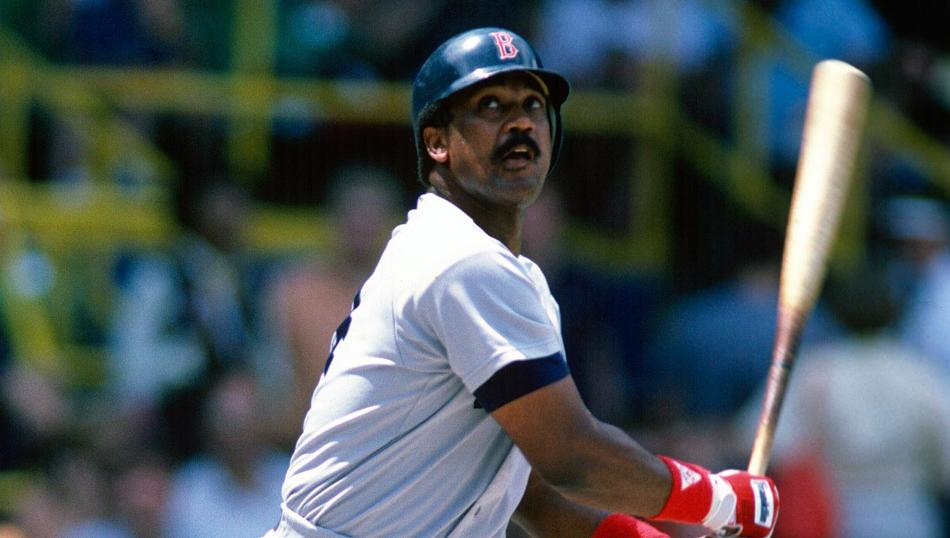

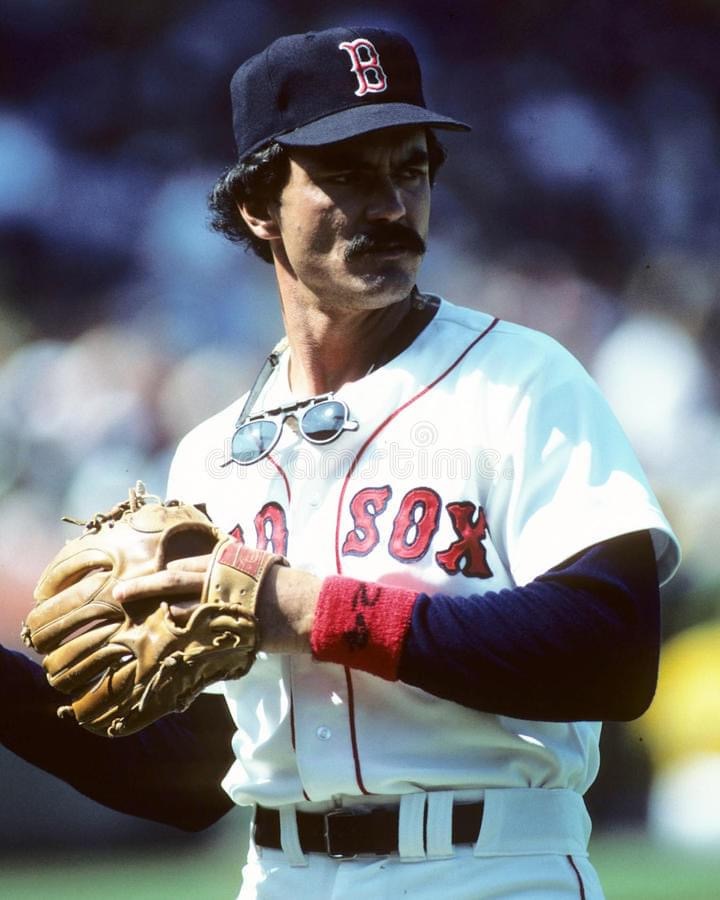

Confident, cocky, stubborn, unyielding, intractable, and fiercely independent are all words that aptly describe the personality of Ted Williams. Those qualities were integral parts of The Splendid Splinter’s persona from the time he first joined the Boston Red Sox in 1939 until he ended his playing career with the team 21 years later in 1960. The aforementioned attributes contributed greatly to the controversial nature of Williams’ career, and also to the tumultuous relationship he shared with the press his entire time in Boston. Yet, those very same character traits helped to make Williams arguably the greatest hitter in baseball history. A six-time batting champion, Williams posted a lifetime batting average of .344 and compiled a total of 521 home runs, despite missing almost five full seasons due to time spent in the United States Military during the Second World War and the Korean War.

Born in San Diego, California on August 30, 1918 as Teddy Samuel Williams, Ted Williams eventually had the name on his birth certificate officially changed to Theodore, although his mother and closest friends continued to call him “Teddy.” Named after his father, Samuel Stuart Williams, and former United States President Teddy Roosevelt, Williams attended Herbert Hoover High School in San Diego, where he excelled in baseball to such an extent that he received offers from the St. Louis Cardinals and the New York Yankees before he even graduated. However, since his mother considered him too young to leave home, Williams signed on instead with the local minor league team, the San Diego Padres. After honing his skills with the Padres, Williams signed an amateur free-agent contract with the Boston Red Sox in 1936. He spent two years in Boston’s minor league farm system before making his major league debut with the team on April 20, 1939.

Williams hardly acted like a typical major league rookie when he joined the Red Sox in spring training that year. Exuding tremendous self-confidence, the cocky 20-year-old surprised many of his teammates with his bold and brazen manner. As Williams prepared for his first batting-practice session with the big club, one of his teammates said to him, “Wait until you see (Jimmie) Foxx hit!” Unimpressed, Williams responded, “Wait until Foxx sees me hit!”

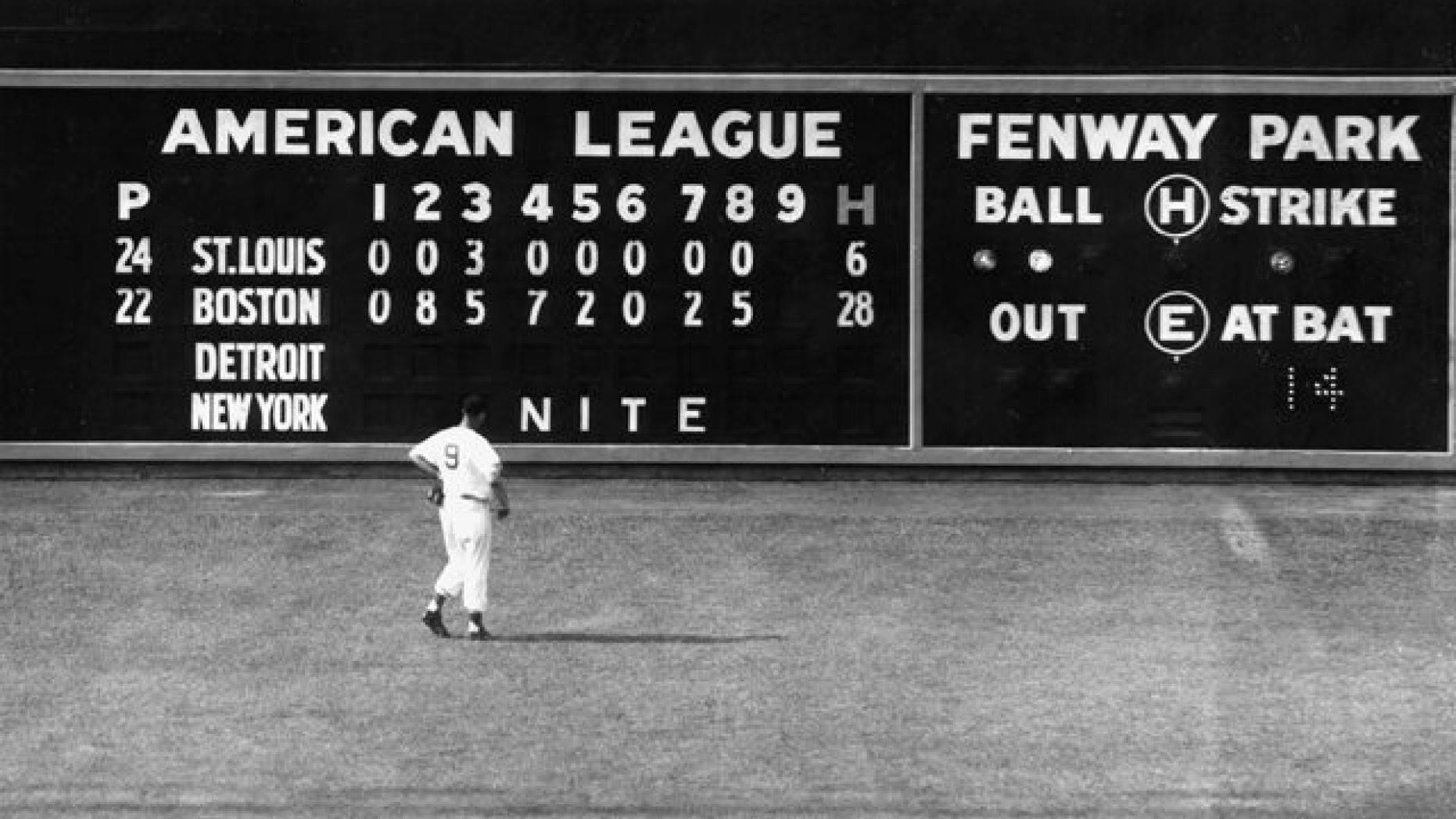

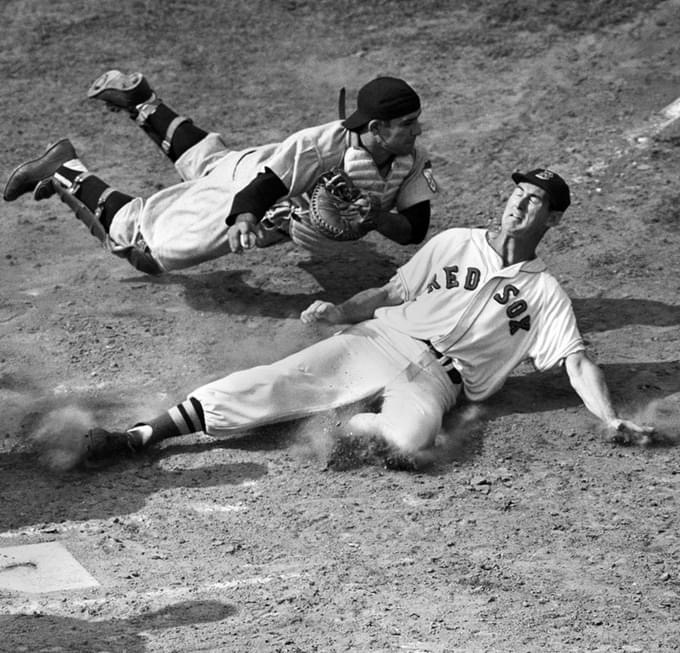

Williams’ brashness might have rubbed his teammates the wrong way had he not had the ability to back up his words. Boston’s new leftfielder had a fabulous rookie season, hitting 31 home runs, scoring 131 runs, batting .327, leading the league with 145 runs batted in and 344 total bases, and finishing fourth in the A.L. MVP voting. He followed that up with another outstanding performance in 1940, batting .344, driving in 113 runs, and leading the league with 134 runs scored and a .442 on-base percentage. However, the best had yet to come.

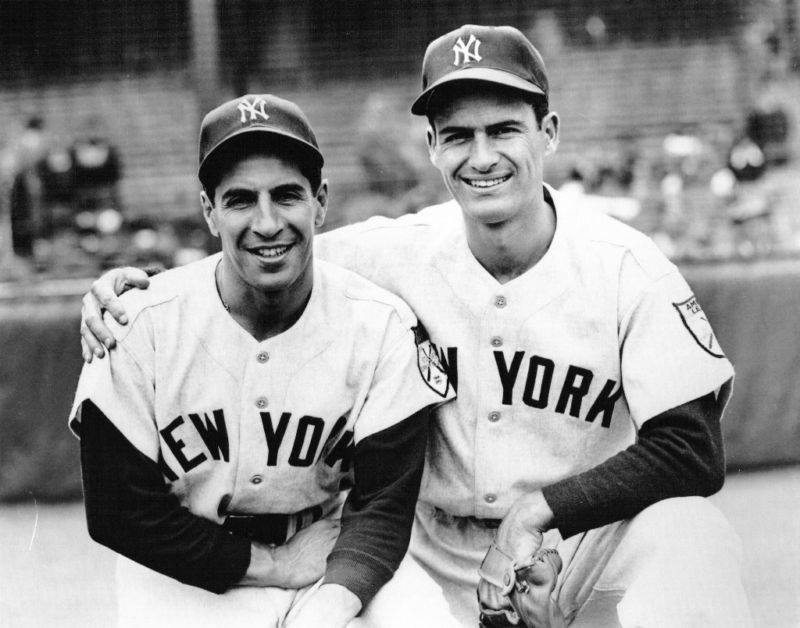

After Joe DiMaggio’s record-setting 56 consecutive game hitting streak captivated the nation earlier in 1941, Williams took center stage during the season’s final few weeks as he strove to become the first man since Bill Terry to hit .400. Williams entered the final day of the season with a batting average of .39955, which would have been rounded up to .400 had he elected not to play in either game of Boston’s season-ending doubleheader against Philadelphia. Offered the option to sit out both games by Red Sox manager Joe Cronin, Williams responded, “If I can’t hit .400 all the way, I don’t deserve it.” In a memorable performance, Williams ended up collecting six hits in eight times at bat over the course of the day, to raise his batting average to .406. No man has hit .400 since. The Splendid Splinter also knocked in 120 runs and led the American League with 37 home runs, 135 runs scored, 147 walks, a .553 on-base percentage, and a .735 slugging percentage. He finished second to DiMaggio in the league MVP voting.

Williams had another great year in 1942, leading the league in eight different offensive categories, including home runs (36), runs batted in (137), and batting average (.356), to win his first triple crown. Yet, even though the Red Sox finished a very respectable second to the Yankees in the American League standings, Williams failed to win the MVP Award. The honor instead went to New York second baseman Joe Gordon.

There is little doubt that the contentious relationship Williams shared with the baseball writers of the day contributed greatly to the lack of support they showed him at times during the MVP balloting. The slugger was moody, hot-tempered, impatient, and somewhat temperamental, especially in his early years in the league. As a result, Williams had numerous confrontations with various members of the press early in his career that jaded their opinion of him throughout the remainder of his playing days. Williams was extremely honest and forthright in his responses to their questions, and didn’t particularly care how they might react to his answers. The writers often misinterpreted Williams’ self-confidence as arrogance, and they conveyed their feelings towards him to the Boston faithful in their newspaper articles. Before long, Red Sox fans turned against Williams as well, finding particularly objectionable his habit of practicing his swing in the outfield during the opposing team’s at-bats. Boston fans believed the sport’s greatest hitter didn’t pay as much attention to the other aspects of the game as he should have, and they soon took to booing him at every opportunity. Williams responded by refusing to ever again tip his cap to them when they cheered him after hitting a home run.

The media’s unfavorable opinion of Williams also caused the Boston leftfielder to consistently come up short in comparisons made between the American League’s two greatest players of the era – Williams and Joe DiMaggio. Williams was acknowledged to be as fine a hitter as anyone in the game. But the more popular DiMaggio was considered to be the superior all-around player. To his credit, Williams never challenged that assessment. Although he believed he was a slightly better hitter than the Yankee Clipper, Williams often said DiMaggio was superior to him as an all-around player.

The debate as to which player was better was put on hold for three years when the United States entered World War II. Both DiMaggio and Williams entered the service in 1943, with the latter spending the next three years serving as a pilot in the U.S. Navy.

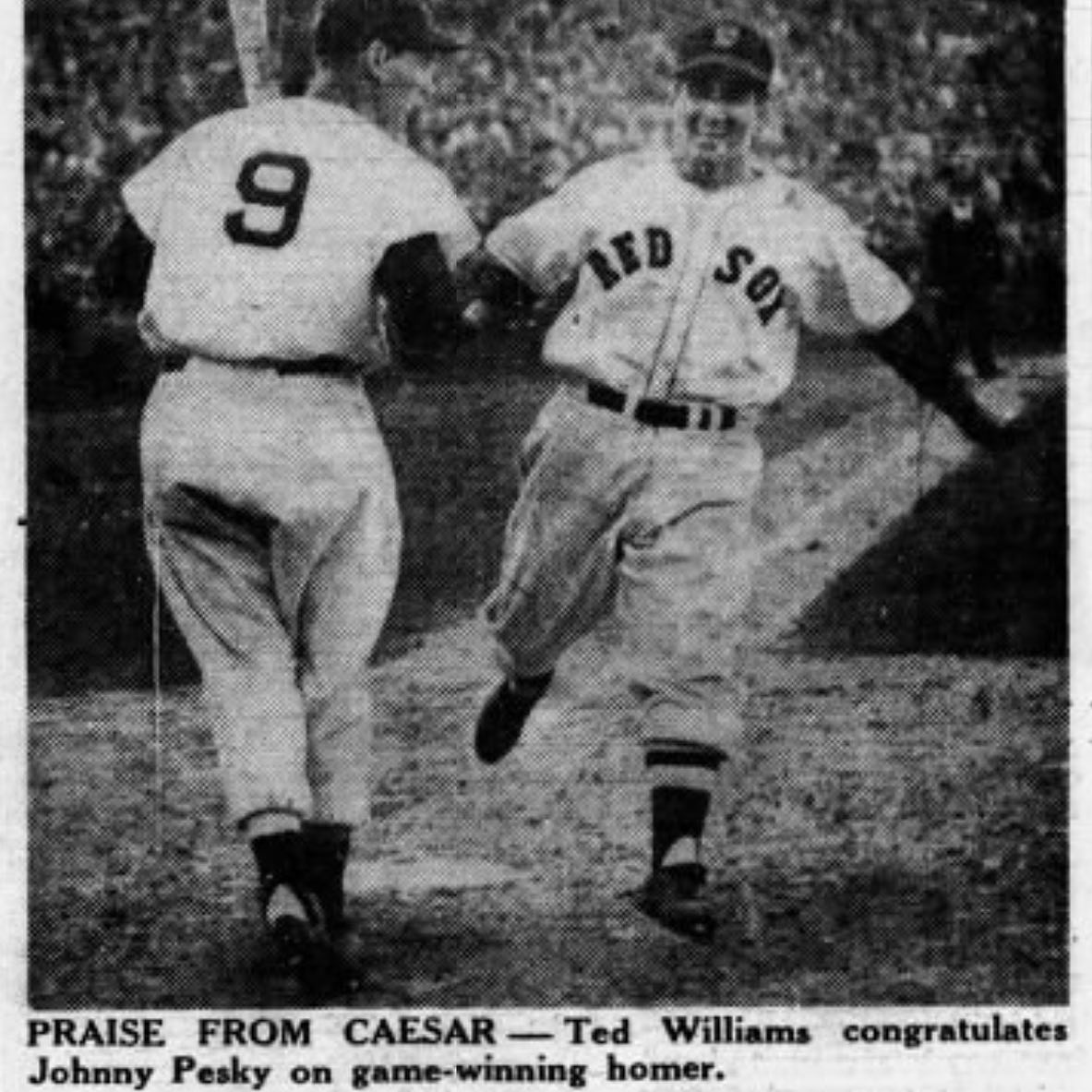

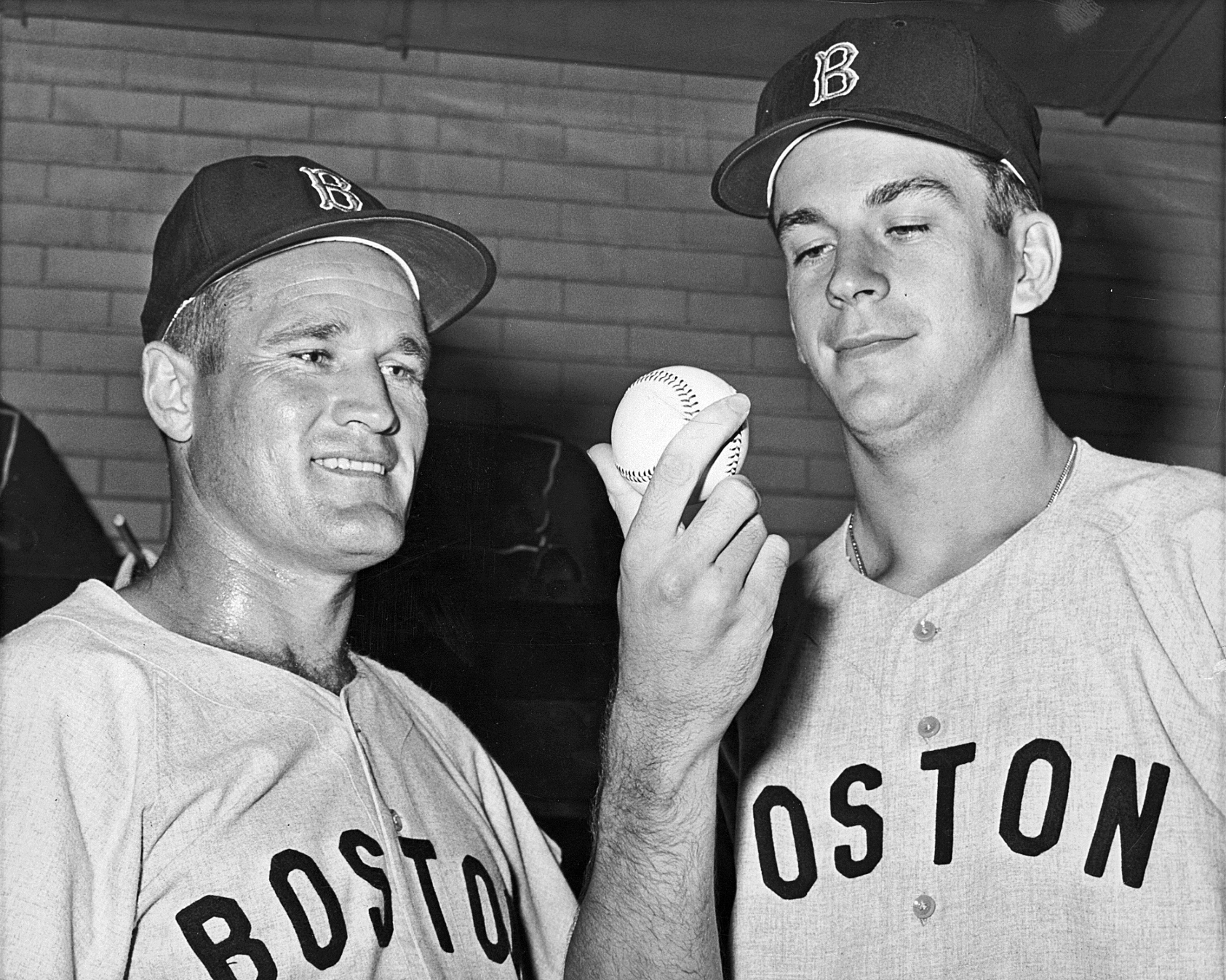

Johnny Pesky, who spent his entire career playing with Williams on the Red Sox, went into the same training program as his teammate. Pesky later recalled the tremendous acumen Williams displayed during the program: “He mastered intricate problems in 15 minutes which took the average cadet an hour, and half of the other cadets there were college grads.”

After serving as a flight instructor at Naval Air Station Pensacola, Williams was stationed in Pearl Harbor awaiting orders to join the China Fleet when the war ended. He finished the war in Hawaii and was released from active duty in January of 1946.

Williams showed no signs of rust when he returned to the major leagues in 1946. If anything, he was physically stronger since he had added a considerable amount of bulk to his slender frame during his time in the service. The 6’3″ slugger had previously depended primarily on his quick wrists and picture-perfect swing to generate power through the hitting zone. But an additional 10-12 pounds of bulk helped Williams become even more of a power threat. He hit 38 home runs in his first year back, knocked in 123 runs, batted .342, and led the league with 142 runs scored, 156 walks, a .497 on-base percentage, and a .667 slugging percentage. The Red Sox captured their first pennant since 1918, and Williams was named the American League’s Most Valuable Player.

Pitcher Bobby Shantz discussed the dilemma pitchers faced when Williams stepped into the batter’s box: “Did they tell me how to pitch to Williams? Sure they did. It was great advice, very encouraging. They said he had no weakness, won’t swing at a bad ball, has the best eyes in the business, and can kill you with one swing. He won’t hit anything bad, but don’t give him anything good.”

Williams won his second triple crown in 1947, leading the league with 32 home runs, 114 runs batted in, and a .343 batting average. Yet, he was edged out by Joe DiMaggio in the MVP balloting, finishing just one point behind the Yankee Clipper in the voting. It later surfaced that one Boston sportswriter left Williams completely off his ballot since he didn’t get along very well with the slugger.

After another outstanding performance the following year in which he captured his fourth batting title with a mark of .369, Williams had his most productive season in 1949. In addition to finishing a close second in the batting race with a mark of .343, Williams established career highs with 43 home runs, 159 runs batted in, 150 runs scored, and 162 walks, leading the league in each category. The Red Sox finished just one game behind the pennant-winning Yankees, and Williams was named the league’s Most Valuable Player for the second time.

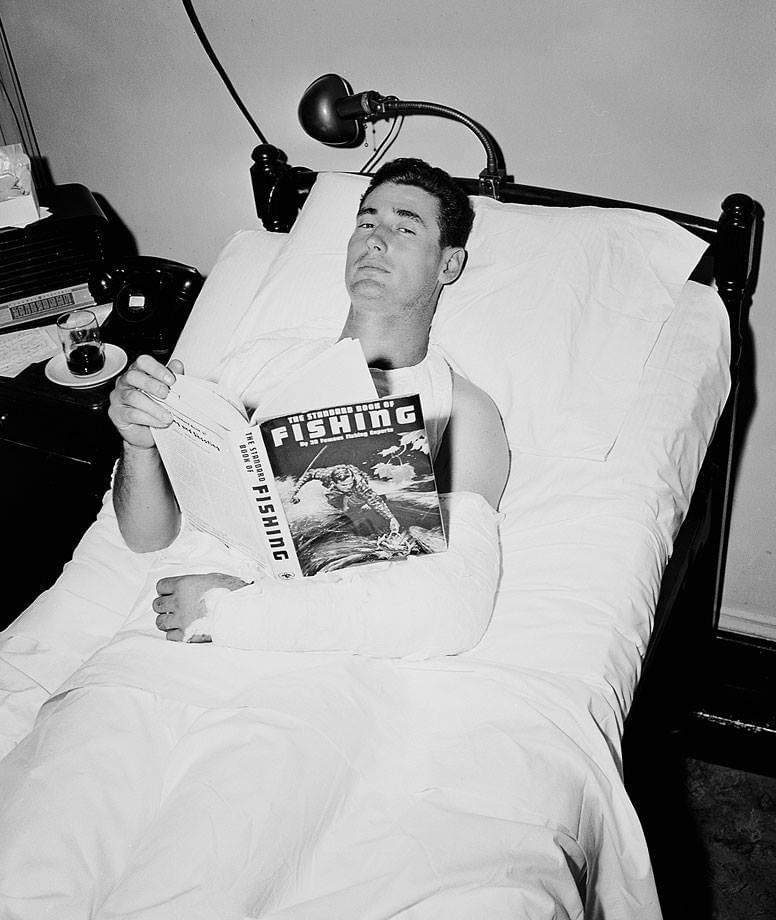

Williams posted outstanding numbers in each of the next two seasons as well, before

being recalled for active duty in the Korean War on May 1, 1952. Eight years removed from his last flight, Williams was not particularly happy about being pressed into service in Korea, but he did what he felt was his patriotic duty. He eventually flew 39 combat missions before being pulled from flight status in June 1953 as the result of an inner ear infection. Williams returned to the Red Sox later that year, batting .407 in his 37 games with the team.

Thirty-five years old at the start of the 1954 campaign, Williams appeared in as many as 130 games in only two of his seven remaining seasons. He never again compiled more than 420 official at-bats in a season. Yet, Williams remained a great hitter to the very end, winning two more batting titles, including leading the league with a mark of .388 in 1957, at the age of 38. Williams homered in the final at-bat of his career, in front of a sparse turnout at Boston’s Fenway Park on a cool, dreary late-September afternoon. Knowing that Williams intended to retire after the game, the Fenway faithful gave him a standing ovation. Always true to himself, Williams later recalled, “I thought about tipping my cap to them for one brief moment. But I just couldn’t bring myself to do it.”

Williams left the sport at the end of that 1960 season with 521 career home runs, 1,839 runs batted in, 1,798 runs scored, 2,654 hits, a .344 batting average, a .634 slugging average, and an all-time best .483 on-base percentage. In addition to his six batting titles, Williams led the league in home runs and runs batted in four times each, runs scored six times, walks eight times, slugging average nine times, and on-base percentage 12 times. He finished in the top five in the league MVP voting a total of nine times, winning the award twice and placing second in the balloting four other times. He appeared in a total of 17 All-Star games.

Stan Musial expressed his admiration for Williams when he stated, “Ted was the greatest hitter of our era. He won six batting titles and served his country for five years, so he would have won more. He loved talking about hitting and was a great student of hitting and pitchers.”

Carl Yastrzemski, who claimed the starting leftfield job in Boston after Williams retired from the game, commented, “They can talk about Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby and Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio and Stan Musial and all the rest, but I’m sure not one of them could hold cards and spades to Williams in his sheer knowledge of hitting. He studied hitting the way a broker studies the stock market, and could spot at a glance mistakes that others couldn’t see in a week.”

Following his retirement, Williams was elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility. In his 1966 induction speech, Williams included a statement calling for the admission into Cooperstown of some of the great Negro League players who never had an opportunity to perform in the major leagues. Williams stated, “I’ve been a very lucky guy to have worn a baseball uniform, and I hope some day the names of Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in some way can be added as a symbol of the great Negro players who are not here only because they weren’t given a chance.”

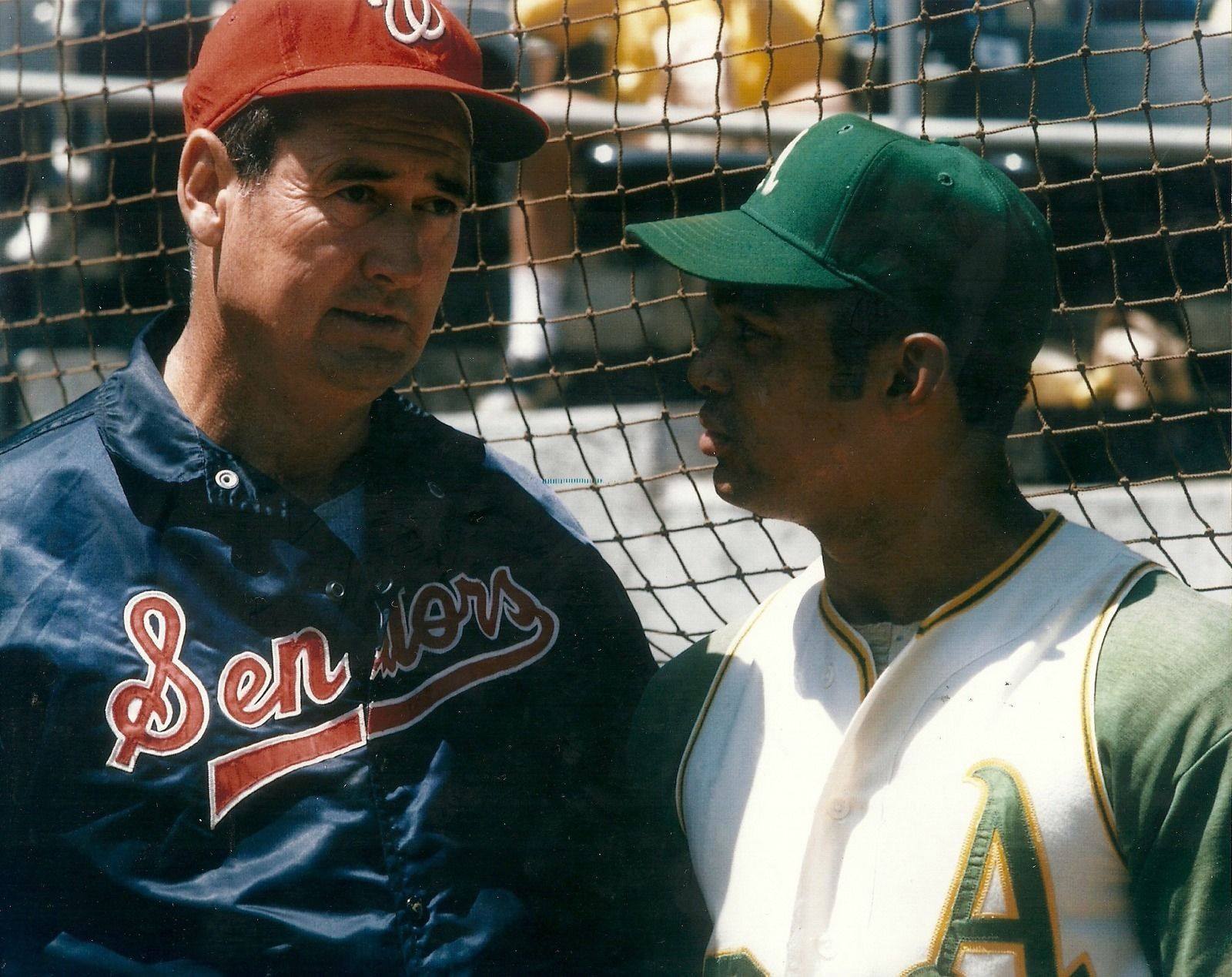

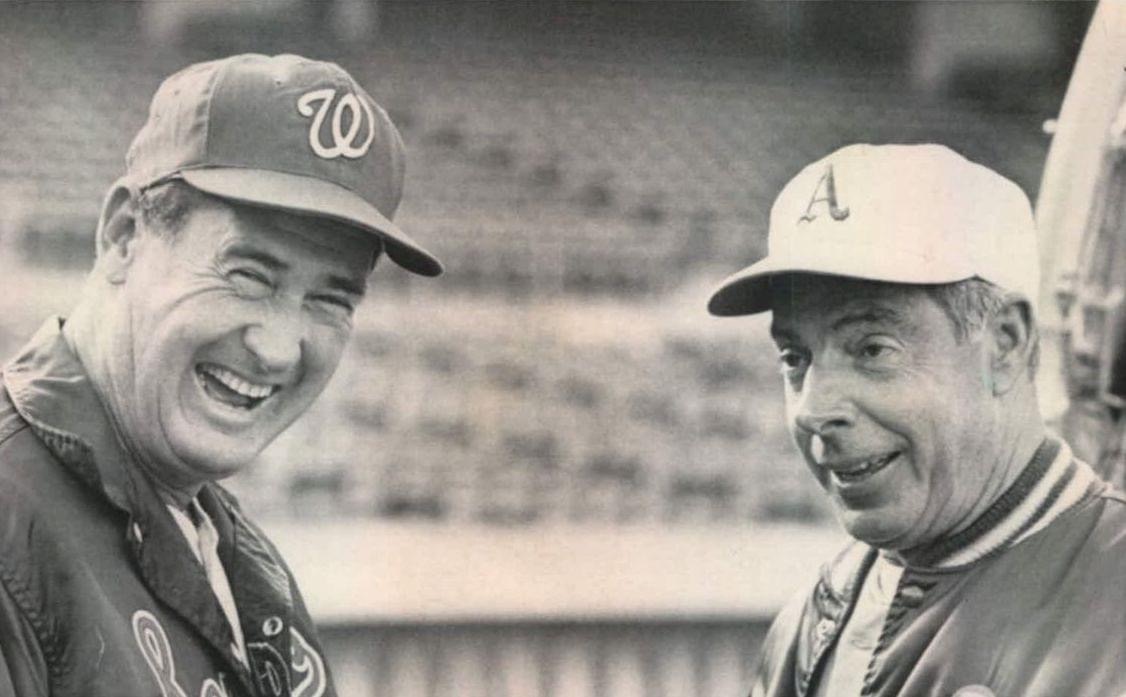

Williams started a second career in 1969 as manager of the Washington Senators, serving in that capacity until shortly after the start of the 1972 campaign, when the team became the Texas Rangers. He subsequently made guest appearances from time to time at Red Sox spring training, until he became unable to do so in later years due to failing health. Williams had a pacemaker installed in November of 2000 and underwent open- heart surgery in January of 2001. After suffering a series of strokes and congestive heart failures, he died of cardiac arrest at the age of 83 on July 5, 2002.

Upon learning of his passing, Dale Petroskey, the President of the Baseball Hall of Fame, expressed his admiration for Williams by saying: “Ted’s passing signals a sad day, not only for baseball fans, but for every American. He was a cultural icon, a larger-than-life personality. He was great enough to become a Hall of Fame player. He was caring enough to be the first Hall of Famer to call for the inclusion of Negro League stars in Cooperstown. He was brave enough to serve our country as a Marine in not one but two global conflicts. Ted Williams is a hero for all generations.”

Pittsburgh Pirates Manager Lloyd McClendon discussed what the Boston legend meant to him: “Ted was everything that was right about the game of baseball. If you really think about it, he was everything that is right about this country. It is certainly a sad day for all of us. He is a man who lost five years of service time serving his country. What he could have done with those years in the prime of his life…it would be awesome to really put those numbers together. He would have probably been the greatest power hitter of all time.”

Ted Williams wrote in his book My Turn At Bat, “A man has to have goals – for a day, for a lifetime – and that was mine, to have people say, ‘There goes Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived.'” Many people feel that Williams reached his ultimate goal.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Vintage Baseball HOT ON EBAY

Card Collections ENDING SOON ON EBAY

MOST WANTED ROOKIE CARDS

VINTAGE SPORTS TICKETS

Baseball Hall of Famers

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

Boston Red Sox (1939-1960)

Managed

Washington Senators (1969-1971)

Texas Rangers (1972)

Similar: None

Linked: Joe DiMaggio, Carl Yastrzemski, Rip Sewell, Lou Boudreau… Rickey Henderson and Tim Raines are the only players besides Williams to steal a base in four different decades… In 1958, Williams hit at a torrid .403 pace over his last 55 games to edge teammate Pete Runnels for the batting title.

Best Season, 1941

He was practically unstoppable, and he should have won the MVP, despite DiMaggio’s 56-gamer. He failed to win the Triple Crown only due to the fact that he refused to swing at bad pitches, leaving him five RBI behind DiMaggio. Against the Yankees, Williams batted .470 in 22 games. Consider this as well: in 1941 major league rules stated that a sacrifice fly counted as a time at-bat. Later that rule was changed and has been that way ever since. Had Williams played under modern rules governing the sac fly (he had six in ’41), his batting average would have been .412! Of the other 11 batters to reach .400 in the 20th century, five wouldn’t have made it under the sac fly rule Williams played under.

Awards and Honors

1942 AL Triple Crown

1946 AL MVP

1947 AL Triple Crown

1949 AL MVP

Post-Season Appearances

1946 World Series

Factoid

Ted Williams got stronger as the season wore on – hitting .349 after the All-Star break over his career, and .339 before. His home run ratio is slightly better in the second half as well. In 1941 he hit .405 before the break and .406 after. His best second-half performance came in 1957 when he tore up the league at a .454 pace after the All-Star game.

Where He Played: Williams, Barry Bonds and Stan Musial fight it out for the title of greatest left fielder in baseball history.

Feats: American League Triple Crown: 1942 and 1946. In neither of those years did Williams win the MVP Award; Hit for the cycle on July 21, 1946; blasted three homers and drove in 8 runs on July 14, 1946; collected more RBI’s than games played (1949); had RBI in 12 straight games (thru September 13, 1942); RBI in 11 consecutive games (thru June 10, 1950); homered in four straight at-bats (September 7th and September 22nd, 1957); combined with Bobby Doerr for 549 homers as teammates (Williams 333, Doerr 216)…

Longest hitting streak came in 1941, when he batted in 23 straight games, hitting .489 (43-for-88), with a .773 SLG, .587 OBP, 7 doubles, 6 homers, 24 RBI, 21 walks, and 32 runs scored. The streak ran from May 15 to June 7. His streak was snapped by Ted Lyons of the White Sox.

Hitting Streaks

23 games (1941)

Williams the Manager

It’s common knowledge that most great players fail to make great managers. With a few exceptions, this is true. Williams skippered the Senators from 1969 to 1971, following them to Texas for the ’72 season. Thus, he was the first manager in Ranger history. He guided the Senators to a winning mark and a 4th place finish in 1969 (largely due to Frank Howard’s slugging), but the team gradually faded over his last three years. He finished his managerial career with a .429 career mark (273-364). Like Rogers Hornsby, Williams failed to communicate well with his players, especially the pitchers, whom he dislkied.

Factoid

On May 15, 1951, the Red Sox celebrated the American League’s 50th anniversary by inviting several old-timers to Fenway Park for their game against the White Sox. Cy Young and Freddy Parent were a few of the old Boston stars who came out. During the game, Ted Williams belted his 300th career home run.

1941: Williams vs. DiMaggio

During Joe DiMaggio’s record hitting streak in 1941, Ted Williams batted .412, while DiMaggio batted .409. Williams batted .389 in April, .436 in May, .372 in June, .429 in July, .402 in August, and .397 in September. He hit .405 before the All-Star break, and .406 after.

Ted’s Toughest Pitchers

Williams claimed Whitey Ford, Eddie Lopat, Bob Lemon, Bob Feller, and Hoyt Wilhelm were his toughest opponents. “I was exposed to pitchers all my life, making a living off their dumbness, off their mistakes, but these were five pitchers who were never dumb. Even after he lost his best stuff – and he had more than anybody – Feller was able to win with smartness.”

Quotes About Williams

“They can talk about Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb and Rogers Hornsby and Lou Gehrig and Joe DiMaggio and Stan Musial and all the rest, but I’m sure not one of them could hold cards and spades to Williams in his sheer knowledge of hitting. He studied hitting the way a broker studies the stock market, and could spot at a glance mistakes that others couldn’t see in a week.” — Carl Yastrzemski

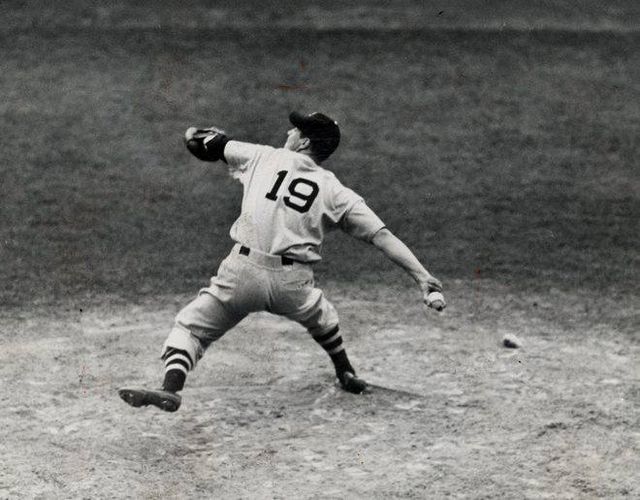

Now Pitching…Ted Williams!

In 1940, 21-year old Ted Williams was rushed to the mound in a blowout game. The right-handed throwing slugger pitched two innings, allowing three hits and one earned run. He didn’t walk anyone, but he did strike out a batter. It was his only pitching appearance in the major leagues.

Factoid

Prior to the 1946 off-season, Red Sox owner Tom Yawkey paid Ted Williams $10,000 not to play in a series of exhibition games after the World Series. Williams had been asked by Bob Feller to take part in his annual off-season tour. “Why doesn’t Feller stay on his own ball club?” Yawkey asked.

Holding Out…For Less

Williams held out in the early part of the 1955 season. It wasn’t because he wanted more money from the Red Sox – it was because he wanted less. He was in the midst of a divorce, and fearing a large baseball salary would complicate the settlement, he declined to report and earn his paycheck. Finally, however, he ended up paying the piper – the court ordered Williams pay $50,000 per year, give up his $42,000 home, pay the $6,000 court costs, and turn over his 1954 Cadillac to his ex-wife.

Home Run Facts

Hit his 500th home run on June 17, 1960, against the Cleveland Indians…

Hit seven pinch-hit homers; hit two in one game 37 times; three in one game on July 14, 1946 at Fenway; clubbed five game-winning homers in 1-0 games (most in history); his 29 homers in 1960 were the most by any player in his final year until Dave Kingman bested him in 1984… Like many great AL sluggers, Williams hit his most homers on the road in Detroit’s Briggs Stadium (later Tiger Stadium). Williams blasted 55 against the Tigers in their home park. He hit 43 in Cleveland, 35 in Comiskey Park, 34 in Shibe Park, 33 in St. Louis, and 30 in Yankee Stadium… Williams blasted 13 extra-inning home runs, ranking among the all-time leaders… 17 total Grand Slams – 1939 (2), 1940, 1941, 1942, 1946 (2), 1947, 1949, 1950, 1951, 1955 (3), 1957, 1958 (2).

Hall of Fame Artifacts

Several of his bats, as well as his Boston Red Sox jersey and uniform. The Hall of Fame also has fishing equipment used and designed by Williams.

All-Star Selections

1940 AL

1941 AL

1942 AL

1946 AL

1947 AL

1948 AL

1949 AL

1950 AL

1951 AL

1953 AL

1954 AL

1955 AL

1956 AL

1957 AL

1958 AL

1959 AL

1960 AL

Replaced

Fiery Ben Chapman, the high-strung speedster. Chapman moved on to Cleveland in 1939, Williams rookie season. Doc Cramer and Joe Vosmik joined Ted in the Sox outfield for his freshman campaign.

Replaced By

In 1960, his final season, Williams (41) was almost as old as fellow Red Sox outfielders Gary Geiger (23) and Lou Clinton (22) combined. In 1961, Carl Yastrzemski replaced Williams in left field and of course, went on to a Hall of Fame career of his own. Also that season, Jackie Jensen returned to Boston, after missing a year due to his fear of flying.

Best Strength as a Player

Hitting ability.

Largest Weakness as a Player

Speed

Other Resources & Links

Coming Soon

If you would like to add a link or add information for player pages, please contact us here.