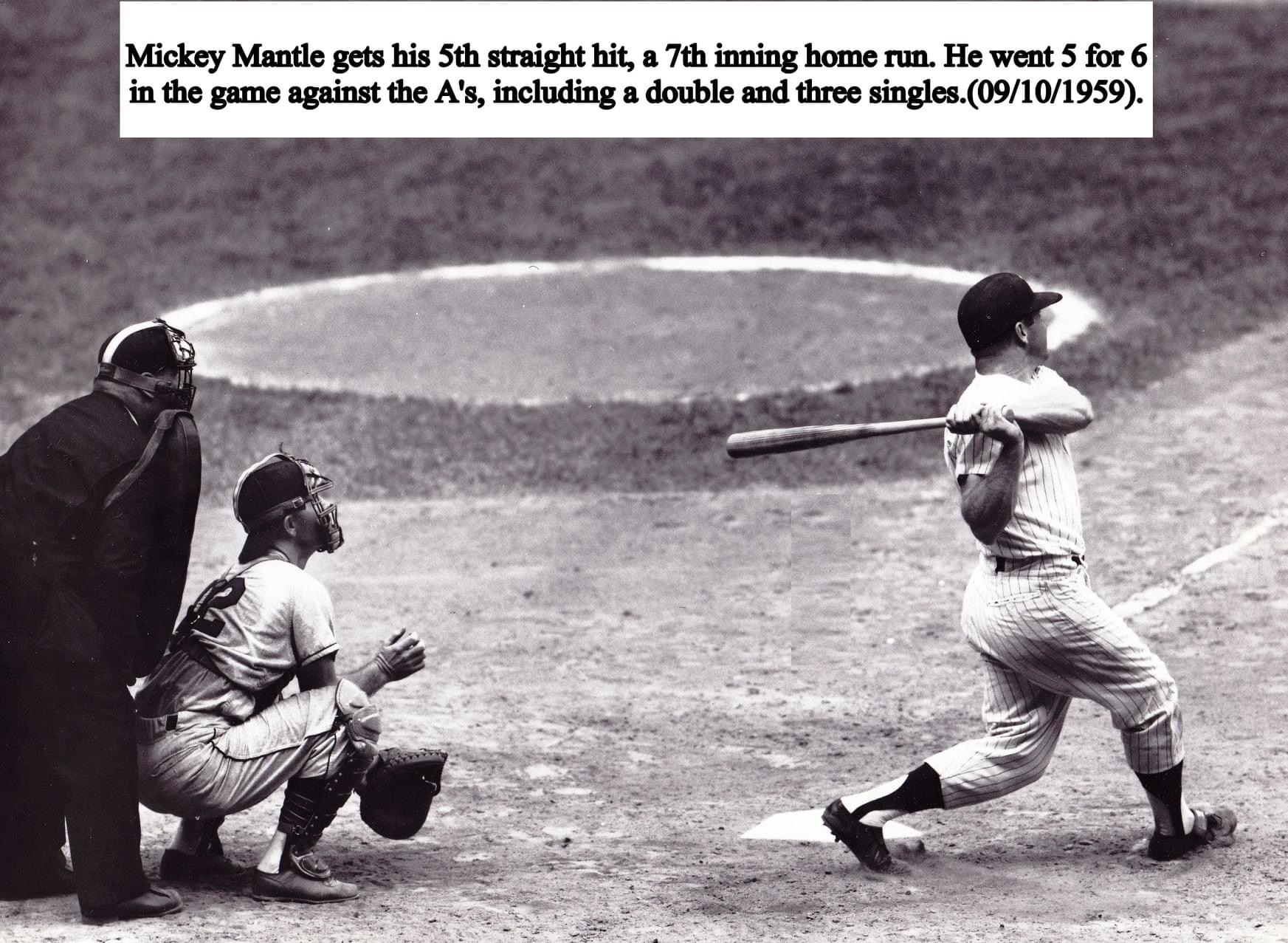

Mickey Mantle Career Highlights

Mickey Mantle Career Highlights

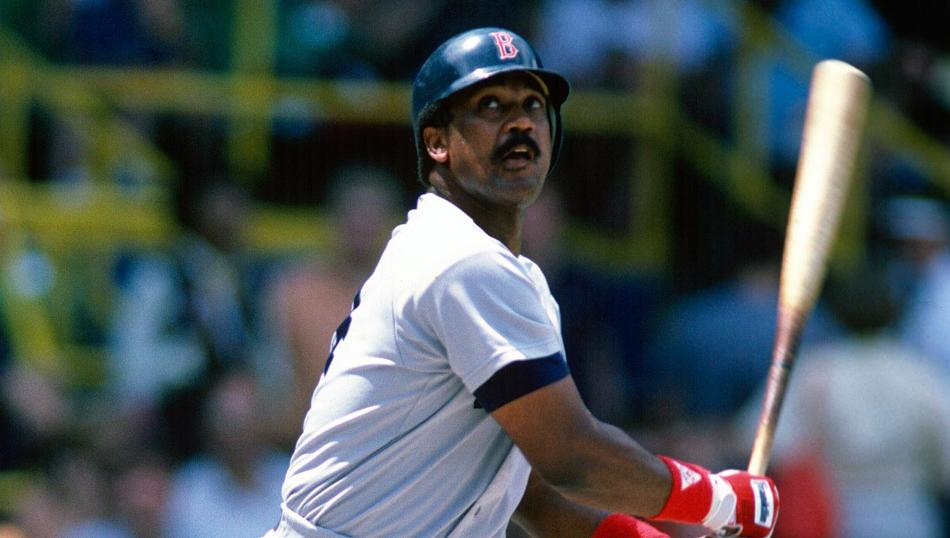

Positions: Centerfielder and First Baseman

Bats: Both • Throws: Right

5-11, 195lb (180cm, 88kg)

Born: October 20, 1931 in Spavinaw, OK

Died: August 13, 1995 in Dallas, TX

Buried: Sparkman-Hillcrest Memorial Park, Dallas, TX

High School: Commerce HS (Commerce, OK)

Debut: April 17, 1951 (8,352nd in MLB history)

vs. BOS 4 AB, 1 H, 0 HR, 1 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 28, 1968

vs. BOS 1 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1974. (Voted by BBWAA on 322/365 ballots)

View Mickey Mantle’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Mickey Charles Mantle

Nicknames: The Mick, The Commerce Comet or Muscles

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1951

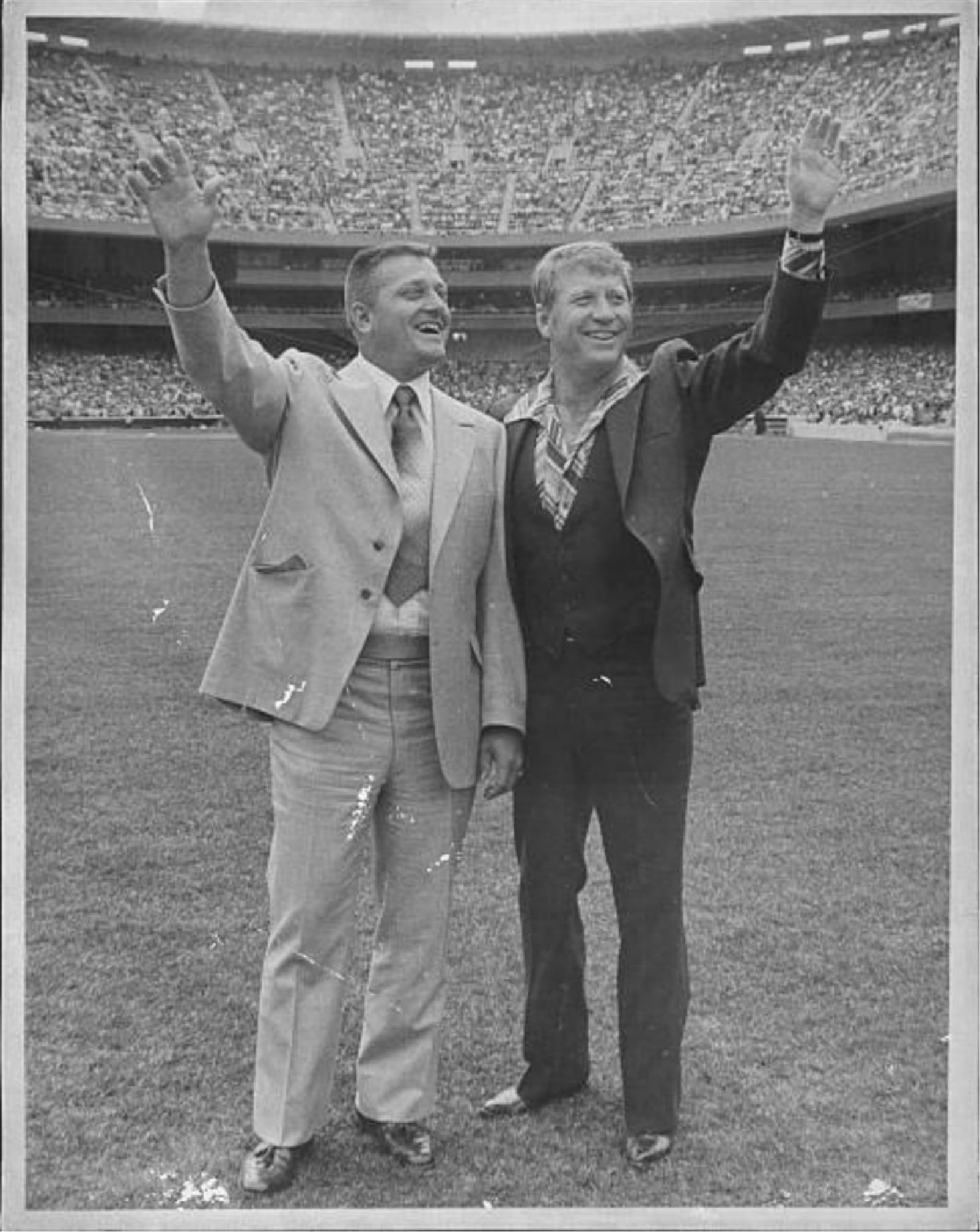

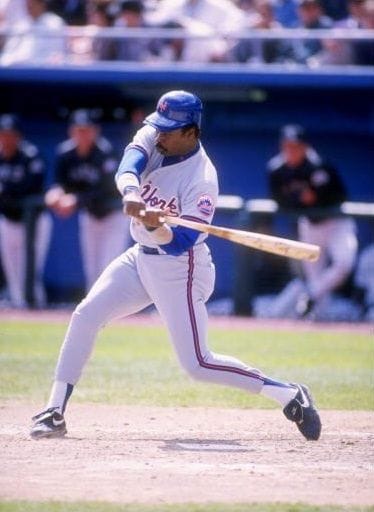

Willie Mays

Mickey Mantle

Roy McMillan

Pete Runnels

Frank Thomas

Johnny Logan

Bob Friend

Rocky Bridges

Gil McDougald

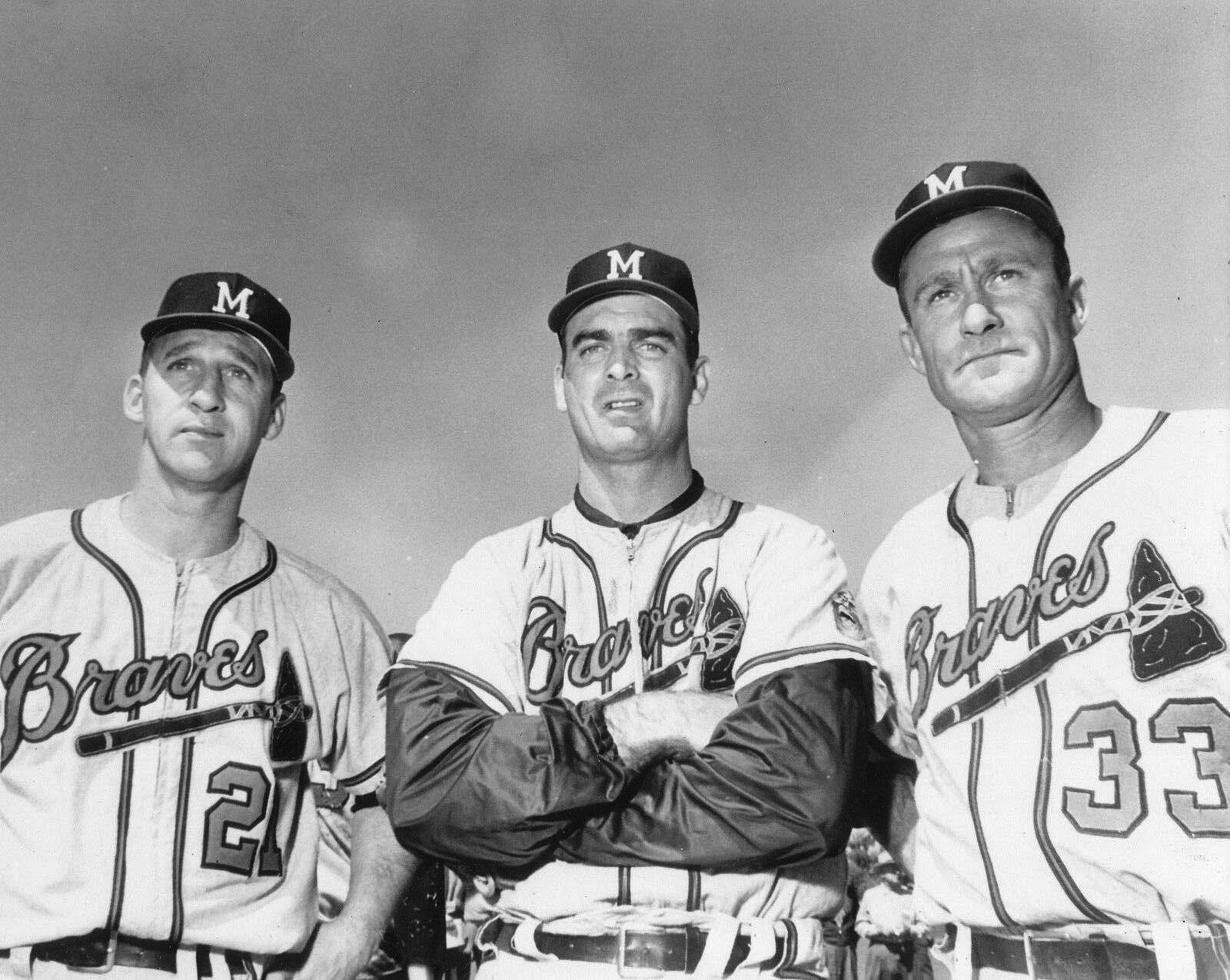

The Mickey Mantle Teammate Team

C: Yogi Berra

1B: Moose Skowron

2B: Billy Martin

3B: Clete Boyer

SS: Phil Rizzuto

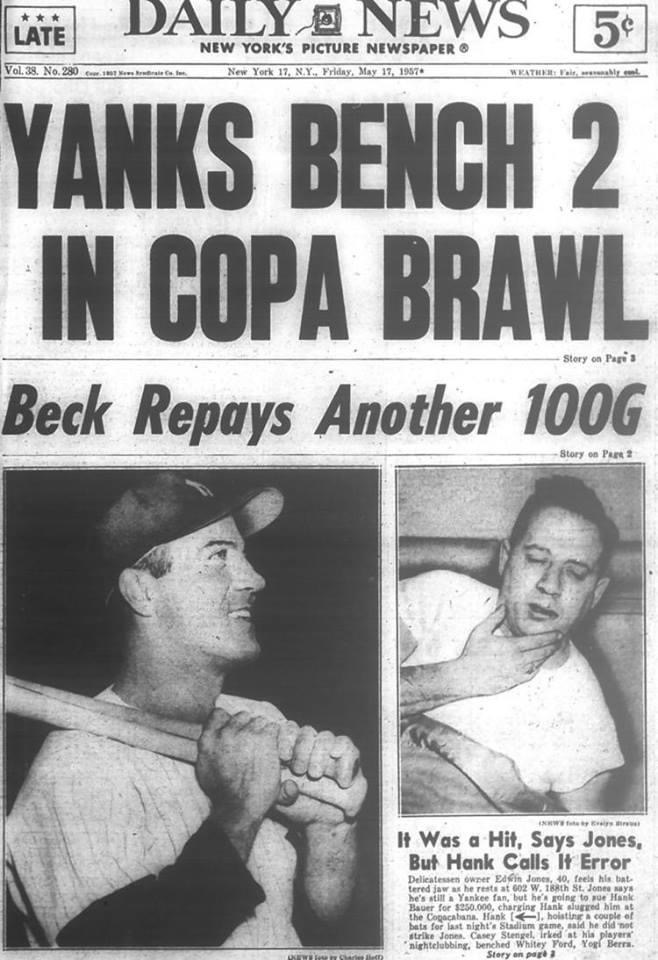

LF: Hank Bauer

CF: Joe DiMaggio

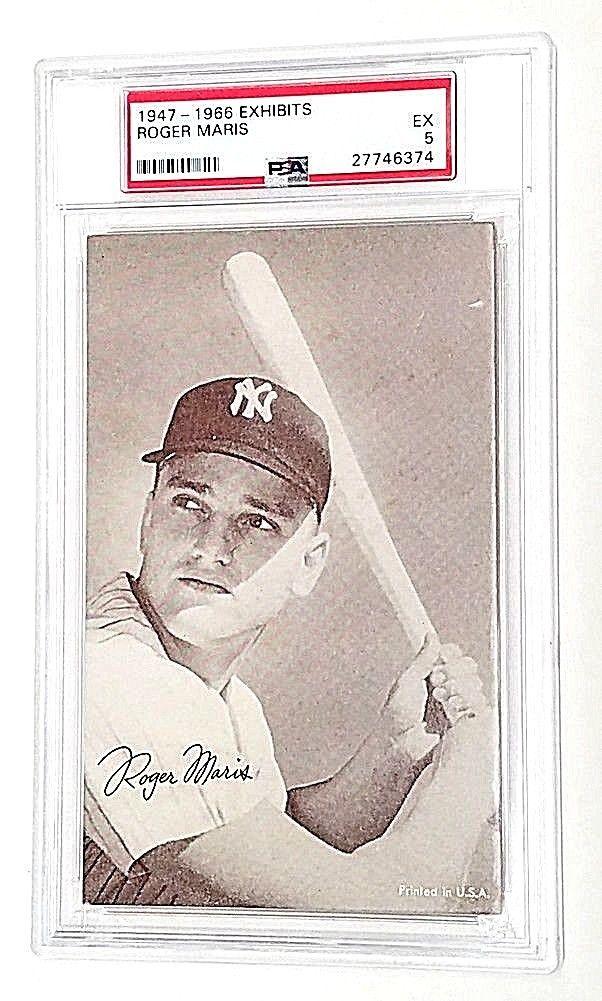

RF: Roger Maris

SP: Whitey Ford

SP: Allie Reynolds

SP: Vic Raschi

SP: Don Larsen

SP: Mel Stottlemyre

RP: Joe Page

M: Casey Stengel

Mickey Mantle Career Highlights

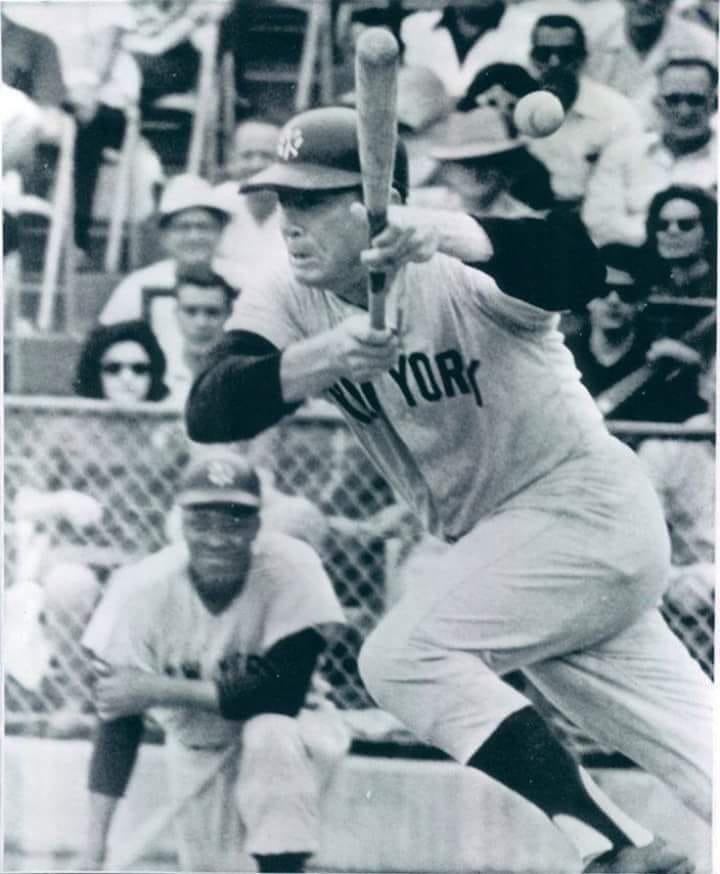

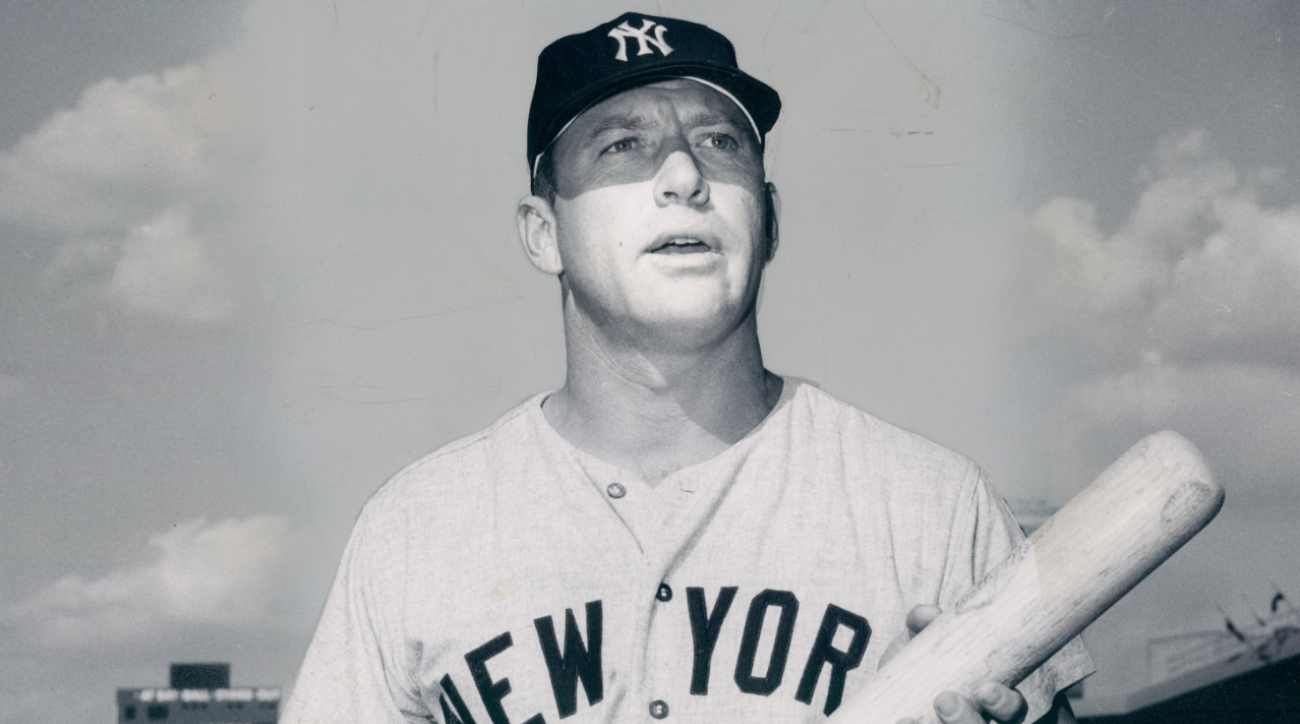

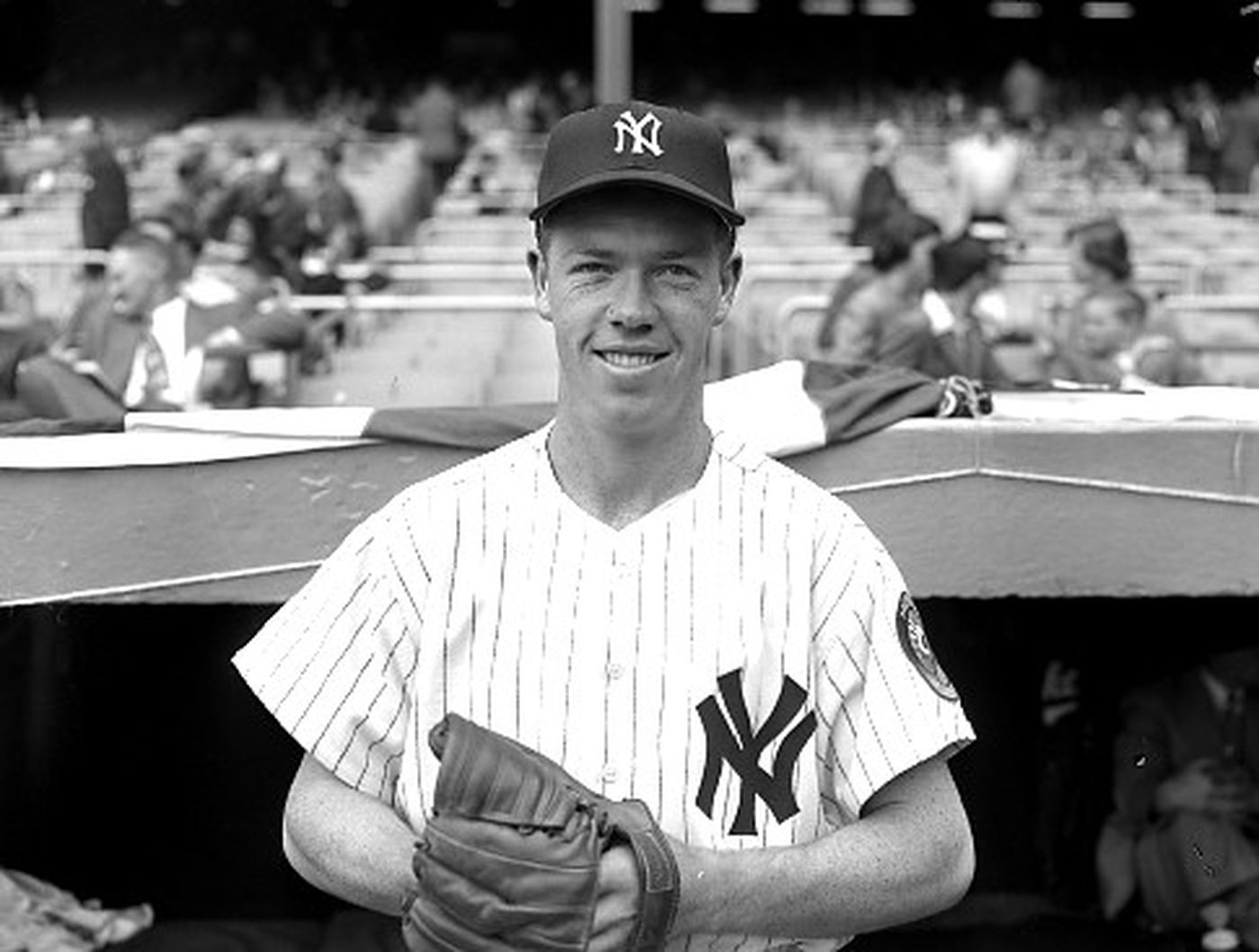

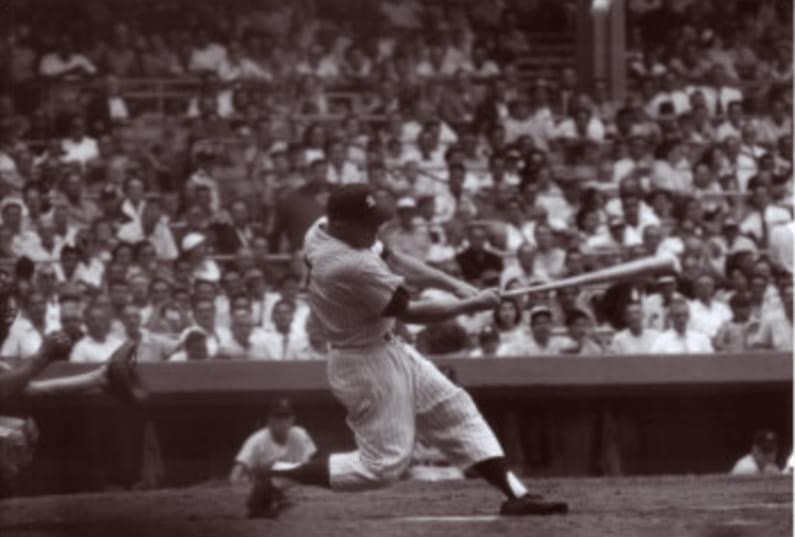

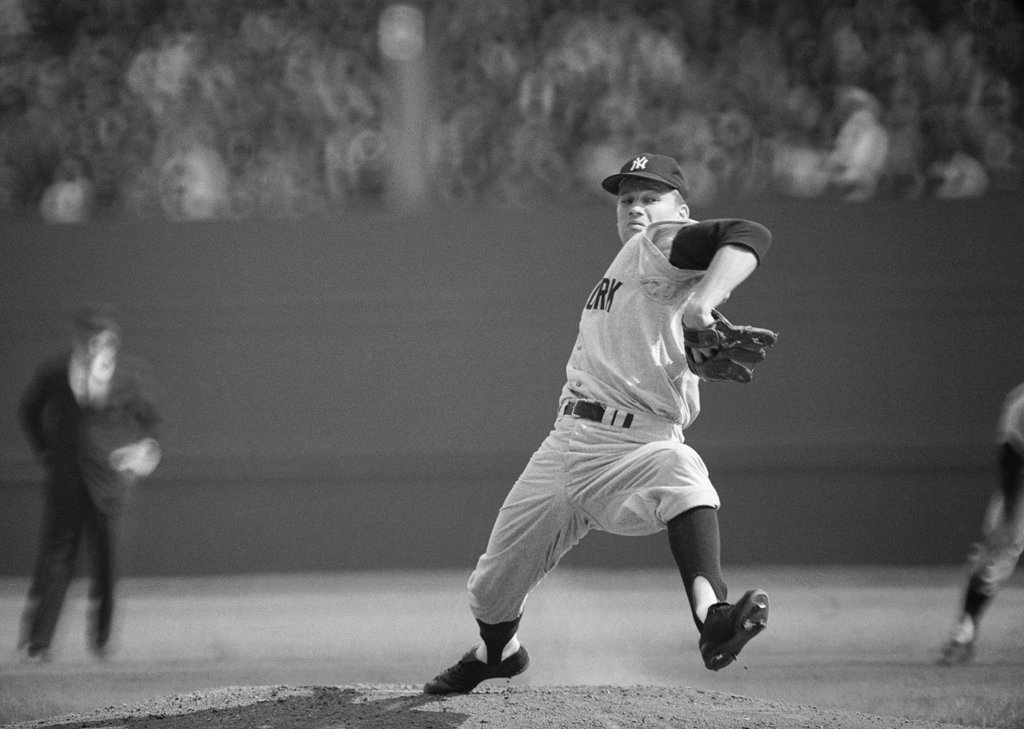

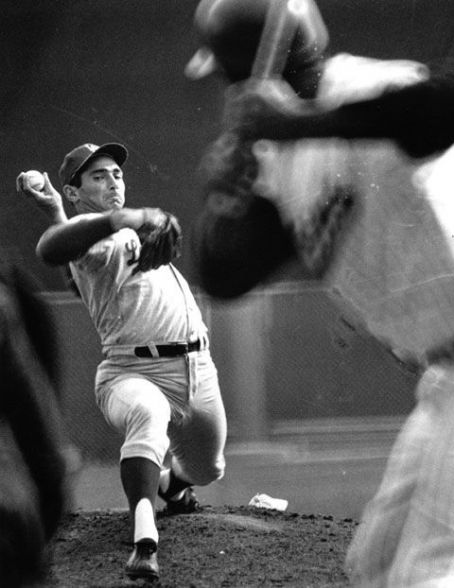

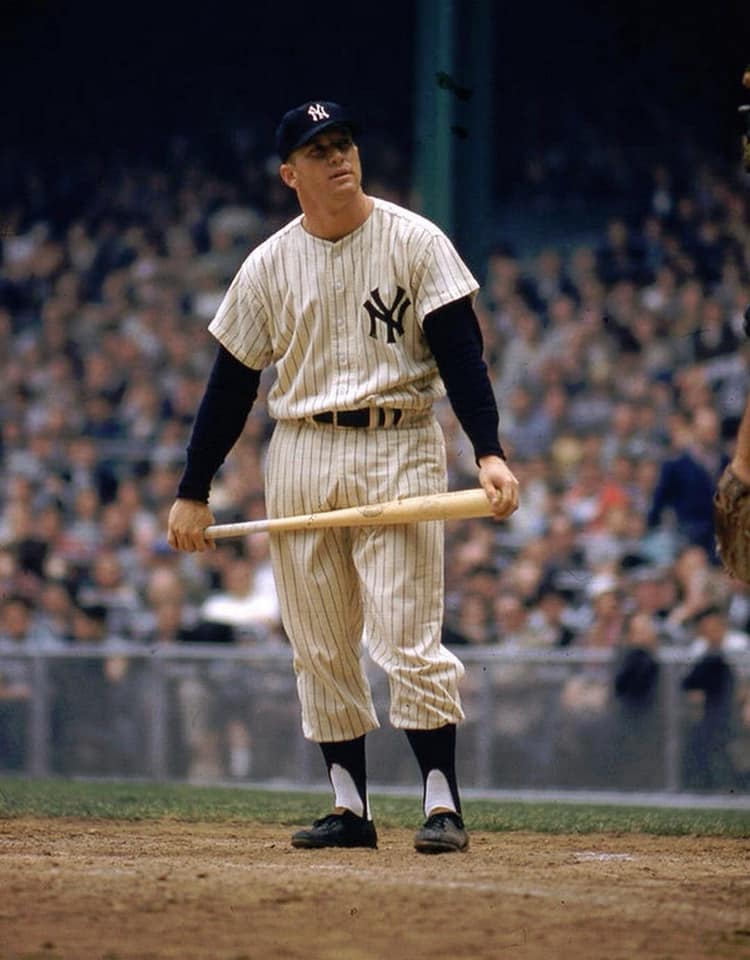

A series of debilitating injuries prevented Mickey Mantle from ever fully living up to the enormous potential he displayed when he first joined the New York Yankees in 1951. Nevertheless, even at less than 100 percent, Mantle had a brilliant 18-year career with the Yankees that clearly established him as the greatest switch-hitter in baseball history, and as one of the most exceptional players ever to play the game.

Born in Spavinaw, Oklahoma in 1951, the son of Elvin Charles Mantle (more commonly known as “Mutt”), Mickey Mantle was bred to be a baseball player. Shortly after Mantle’s family moved to the nearby town of Commerce, Oklahoma when Mickey was four, he was taught to switch-hit by his father and grandfather, who pitched to him righthanded and lefthanded, respectively. Mickey developed into an outstanding all-around athlete at Commerce High School, excelling in both football and basketball, in addition to his first love, baseball. Mantle’s athletic career, though, almost ended prematurely when he sustained a life-threatening injury on the football field. Kicked in the shin during a game, Mantle’s leg soon became infected with osteomyelitis, a crippling disease that would have been incurable had penicillin not been made available just a few years earlier. Although the drug saved Mantle’s leg from amputation, Mickey suffered from the effects of the disease for the rest of his life, and it probably led to many other injuries that eventually robbed him of much of the blinding speed he had during the early stages of his professional career.

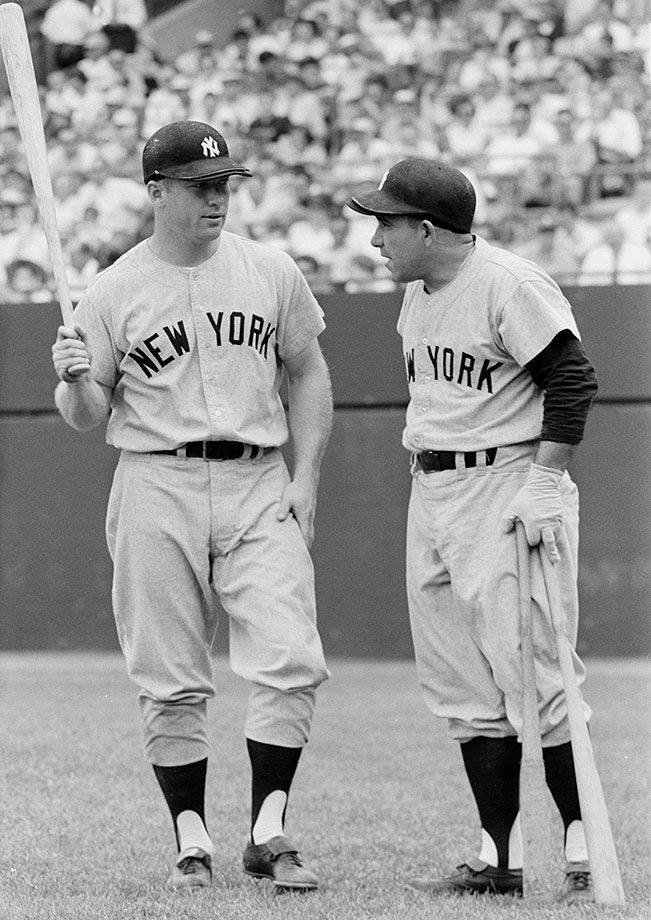

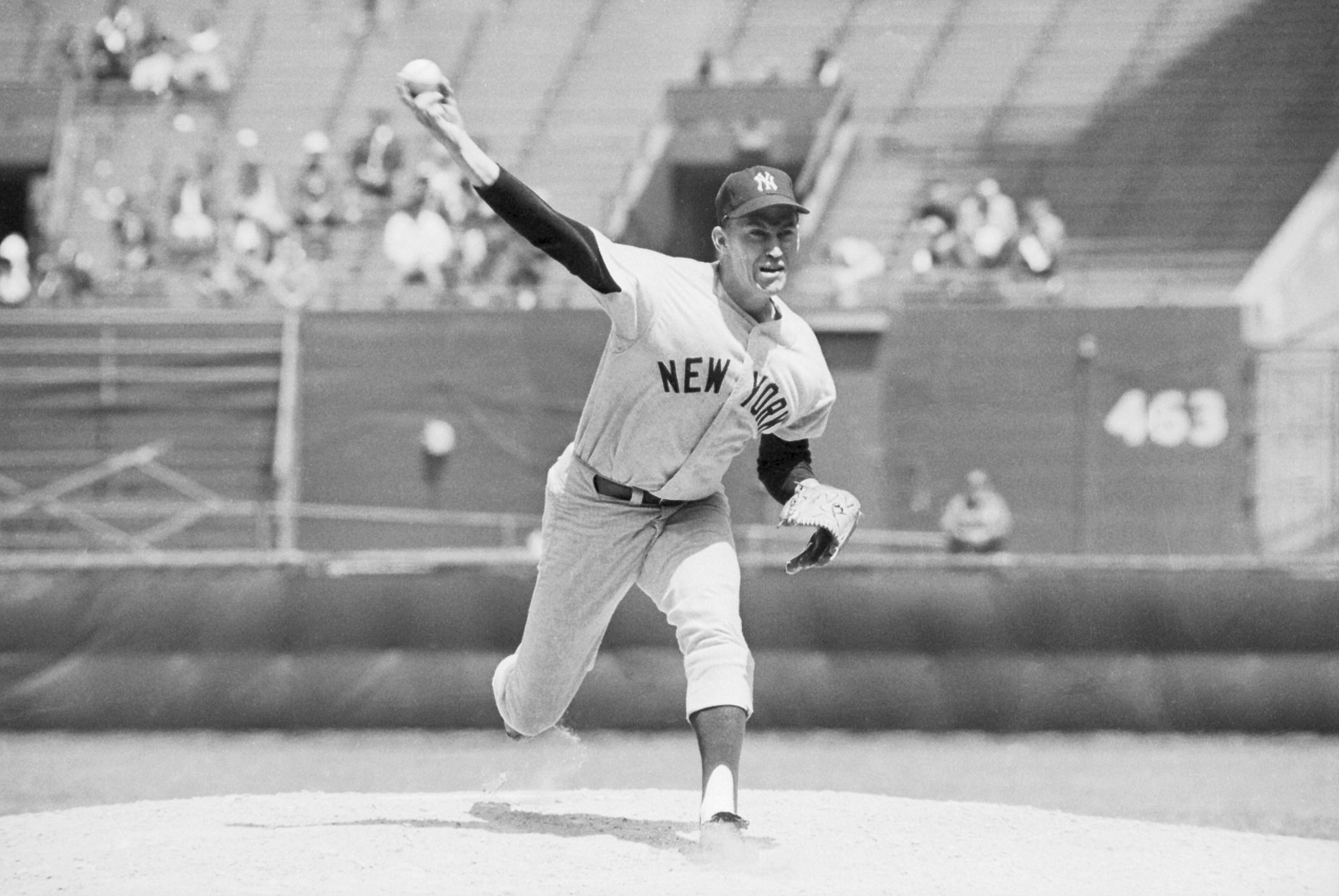

After being signed by New York Yankee scout Tom Greenwade at the tender age of 17 in 1949, Mantle spent two seasons in the Yankee farm system before finally joining the club in 1951. The shy 19-year-old immediately had huge expectations thrust upon him by both Manager Casey Stengel and the New York media. Considered by most people to be the heir apparent to the aging Joe DiMaggio in centerfield, Mantle was built up by Stengel as someone who eventually would become DiMaggio, Babe Ruth, and Lou Gehrig all rolled into one. Observing the switch-hitting outfielder’s blinding speed and awesome power from both sides of the plate, the Yankee manager proclaimed, “He (Mantle) should lead the league in everything. With his combination of speed and power, he should win the triple batting crown every year. In fact, he should do anything he wants to do.” Adding to the pressures placed on Mantle was the uneasiness the insecure country boy felt over being in the big city for the first time in his life.

Unable to live up to his advanced billing early in his rookie season, Mantle found himself striking out frequently and often being booed by Yankee fans, who believed everything they had read and heard about the talented youngster. Before long, the struggling outfielder was sent down to the minor leagues, where he eventually righted himself. Returning to New York later in the year, Mantle finished his rookie season with decent numbers, hitting 13 home runs, knocking in 65 runs, and batting .267 in 341 at-bats. However, he experienced the first in a series of crippling injuries in that year’s World Series that ended up severely limiting his playing time and robbing him of much of his great speed throughout the remainder of his career.

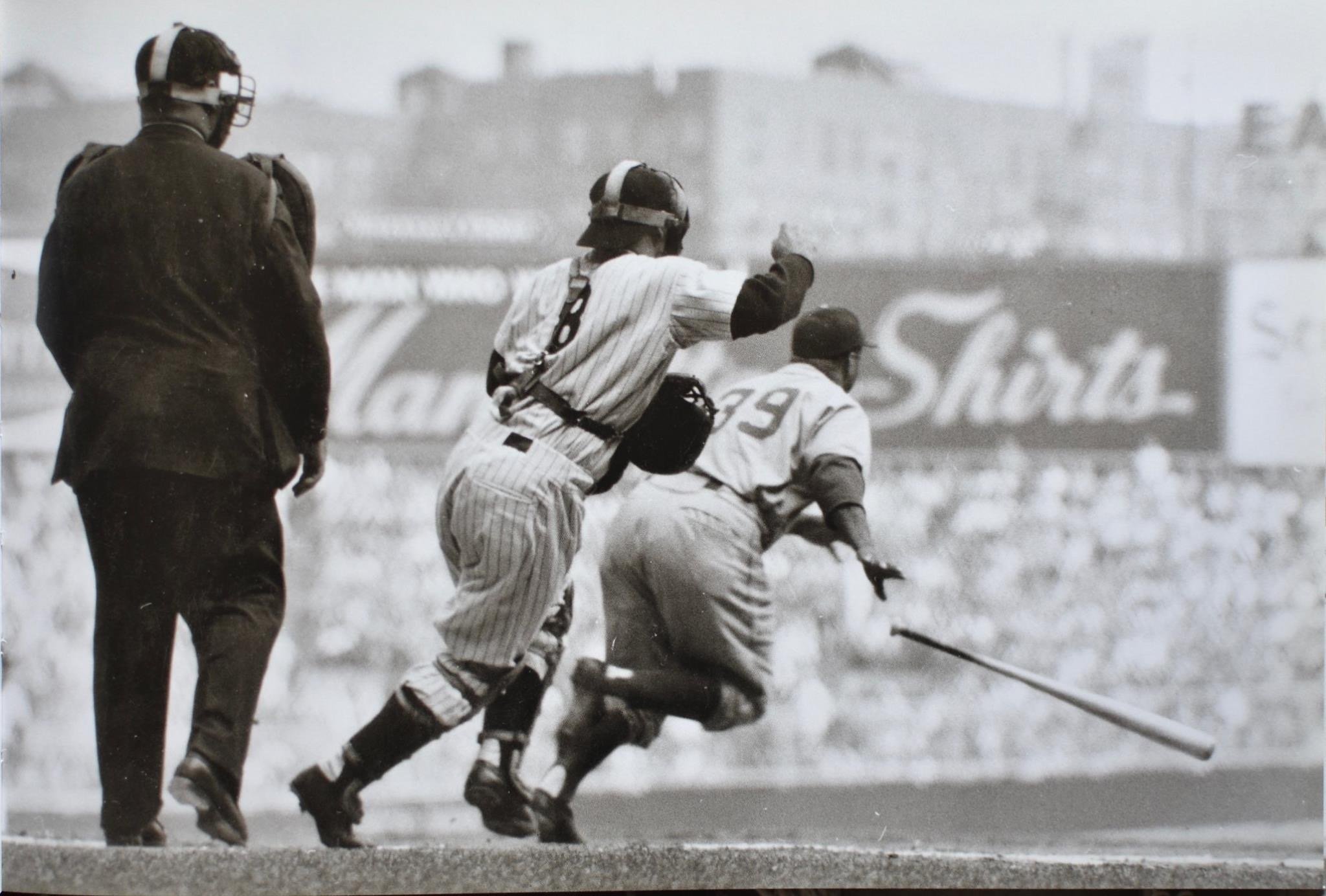

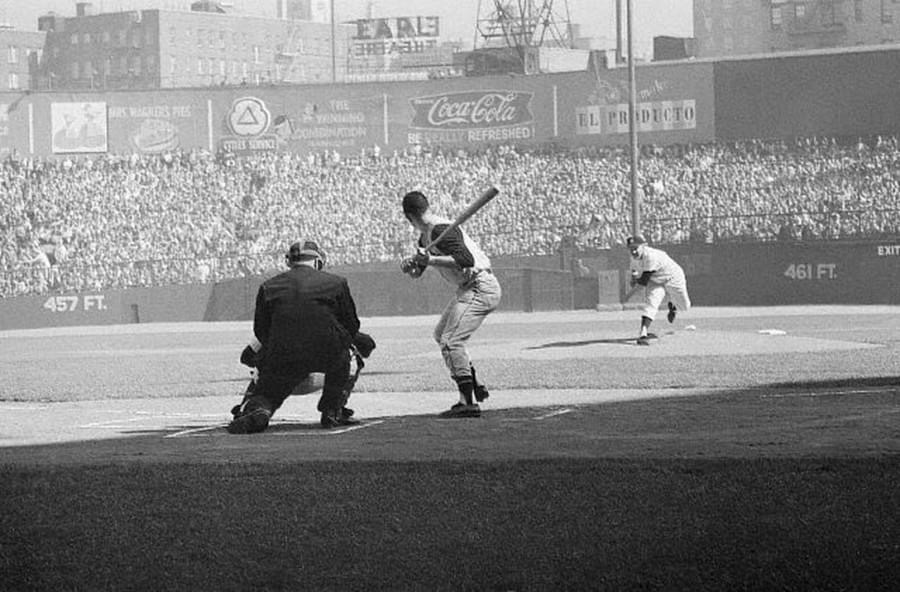

Playing rightfield in Yankee Stadium, Mantle moved towards right-center to catch a fly ball hit by the Giants Willie Mays. With Mantle all set to make the play, centerfielder Joe DiMaggio called off his teammate at the last moment. Stopping abruptly to avoid a collision, Mantle caught his right foot in an outfield drainage ditch, seriously injuring his leg and causing him to be carried off the field on a stretcher. The injury prevented Mantle from ever again playing at 100 percent capacity.

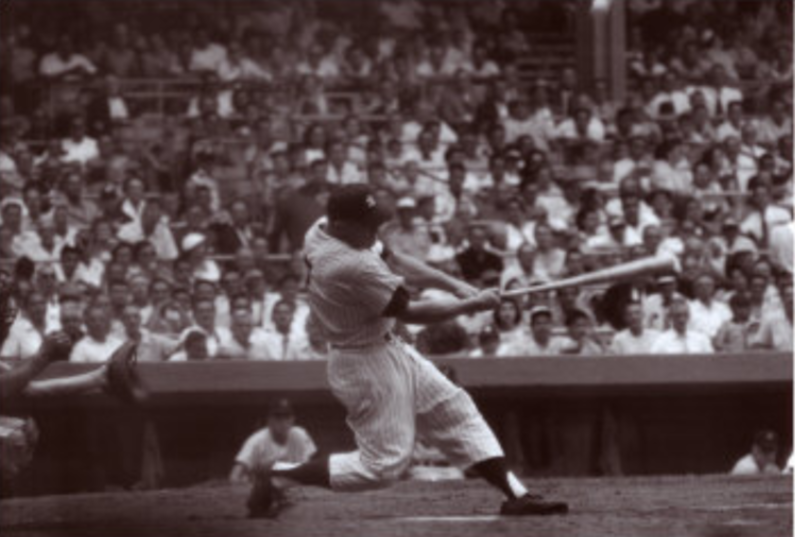

Yet, even at less than 100 percent, Mantle had enough natural ability to become a truly great player. He was thick throughout his 5’11”, 200-pound frame, extremely muscular, and also exceptionally fast, even after losing some of his great speed. Although Mantle always maintained he was a better righthanded hitter, he had equal power from both sides of the plate, possessing the ability to drive the ball more than 500 feet either as a lefthanded or righthanded batter.

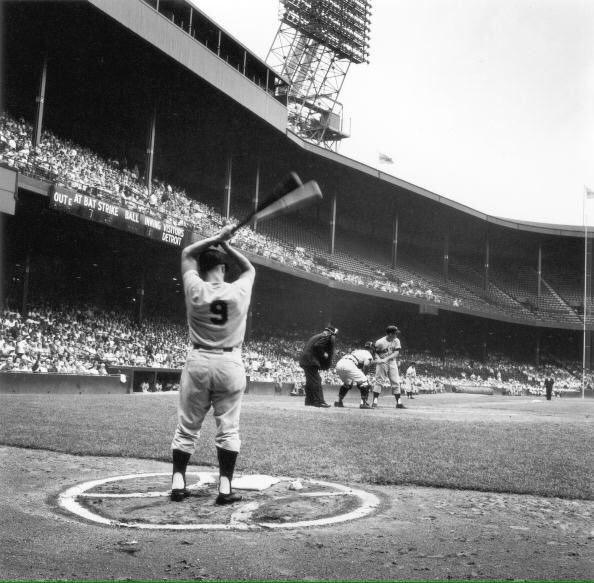

Returning to the Yankees at the start of the 1952 campaign, Mantle took over the starting centerfield job from the recently-retired DiMaggio. Although he continued to strike out regularly, fanning a total of 111 times, Mantle had a very solid second season, hitting 23 home runs, driving in 87 runs, scoring 94 others, batting .311, and making the All-Star Team for the first of 11 straight times. He also performed quite well in each of the next three seasons, averaging 28 home runs, 98 runs batted in, and 118 runs scored from 1953 to 1955, and batting over .300 in two of those years. Mantle led the American League with 129 runs scored in 1954, and he topped the circuit with 37 home runs, a .433 on-base percentage, and a .611 slugging percentage in 1955. Yet, disappointed by Mantle’s frequent strikeouts and the slugger’s inability to reach the lofty level that had been predicted for him when he first arrived in the big leagues, Yankee fans continued to often voice their displeasure towards the slugger by booing him whenever he failed to fully live up to their expectations.

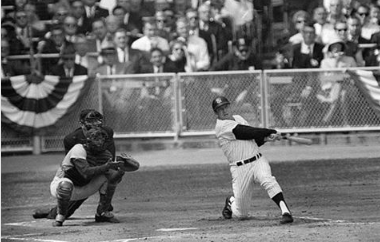

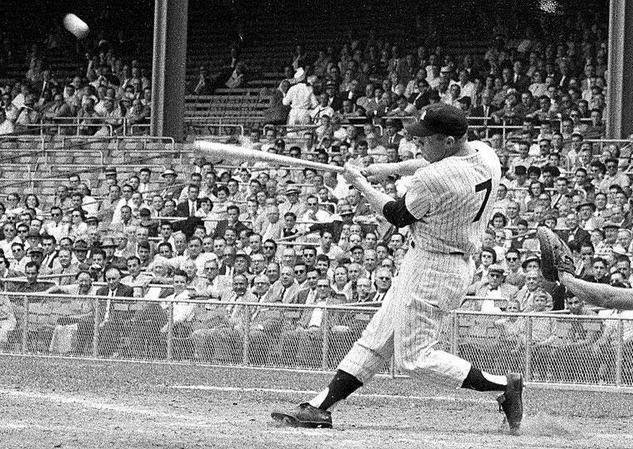

Mantle finally became the darling of the fans in 1956, when he put together the kind of season most people always believed he was capable of having. Mantle won the American League triple crown by leading the league with 52 home runs, 130 runs batted in, and a .353 batting average. He also topped the circuit with 132 runs scored and a .705 slugging percentage, en route to being named the league’s Most Valuable Player for the first of three times, and being awarded the Hickock Belt as the top professional athlete of the year. Mantle had another great season in 1957, hitting 34 home runs, knocking in 94 runs, batting .365, winning his second consecutive MVP Award, and leading the Yankees to their sixth pennant in his first seven years with the team. However, even though Mantle was among the league’s best players in both 1958 and 1959, his numbers fell off somewhat, causing fans of the team to once again boo him at every opportunity. The attitude of the fans towards Mantle began to permanently change the following season, though, after New York’s disappointing third-place finish in 1959 prompted the team to acquire Roger Maris from the Kansas City Athletics for five players.

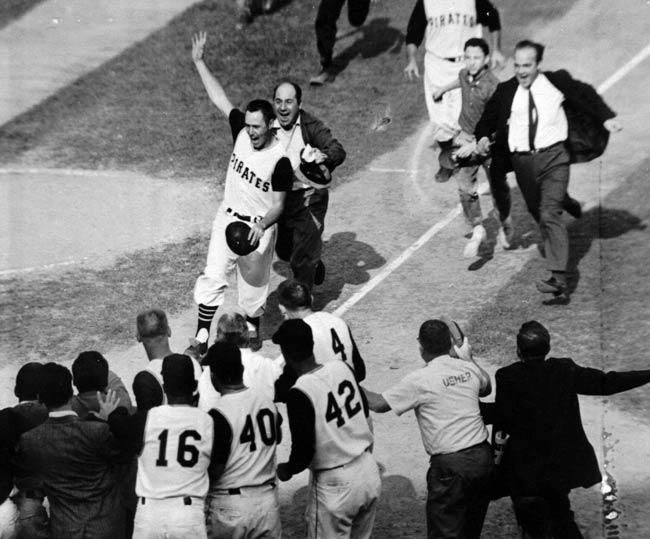

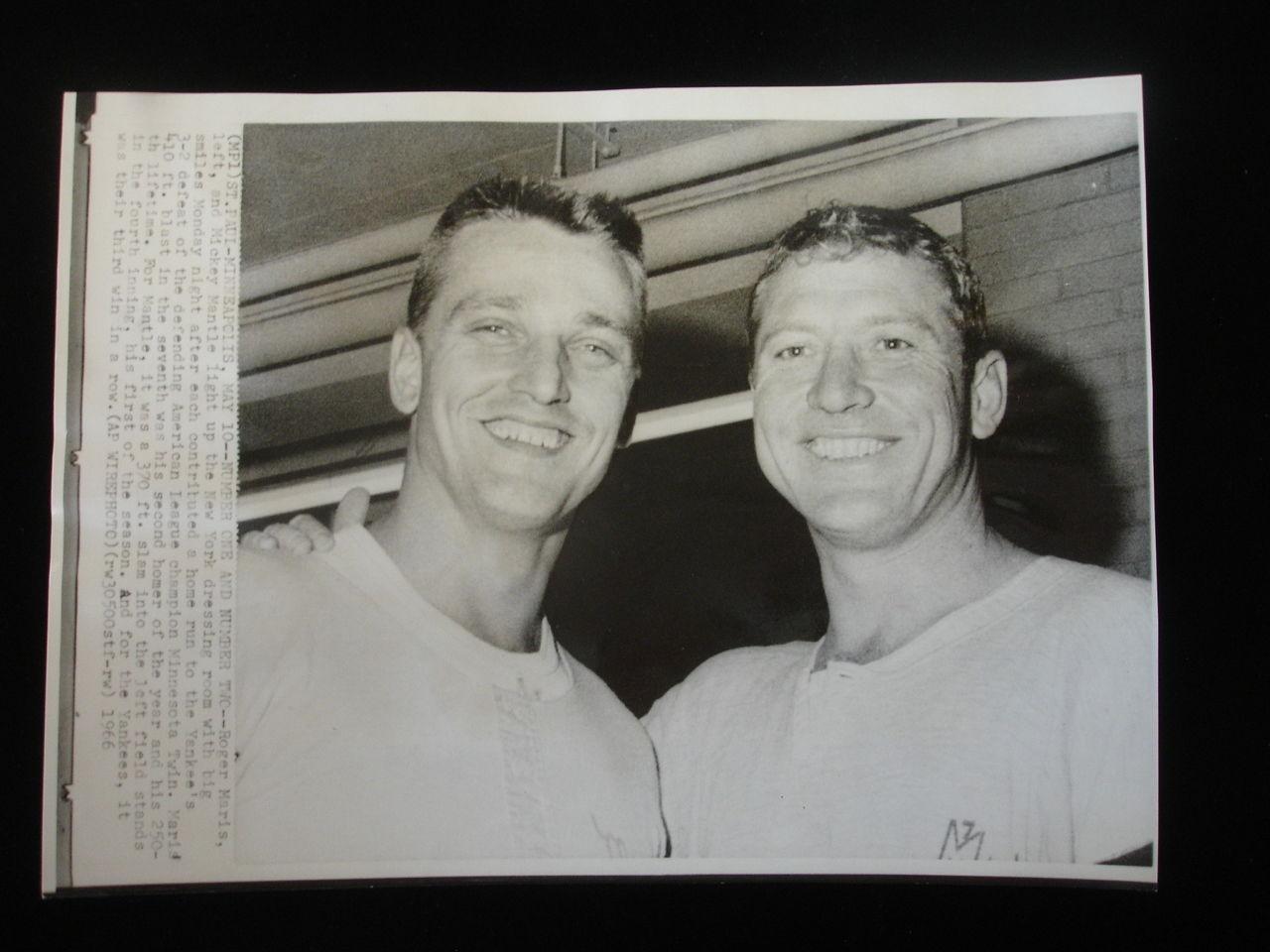

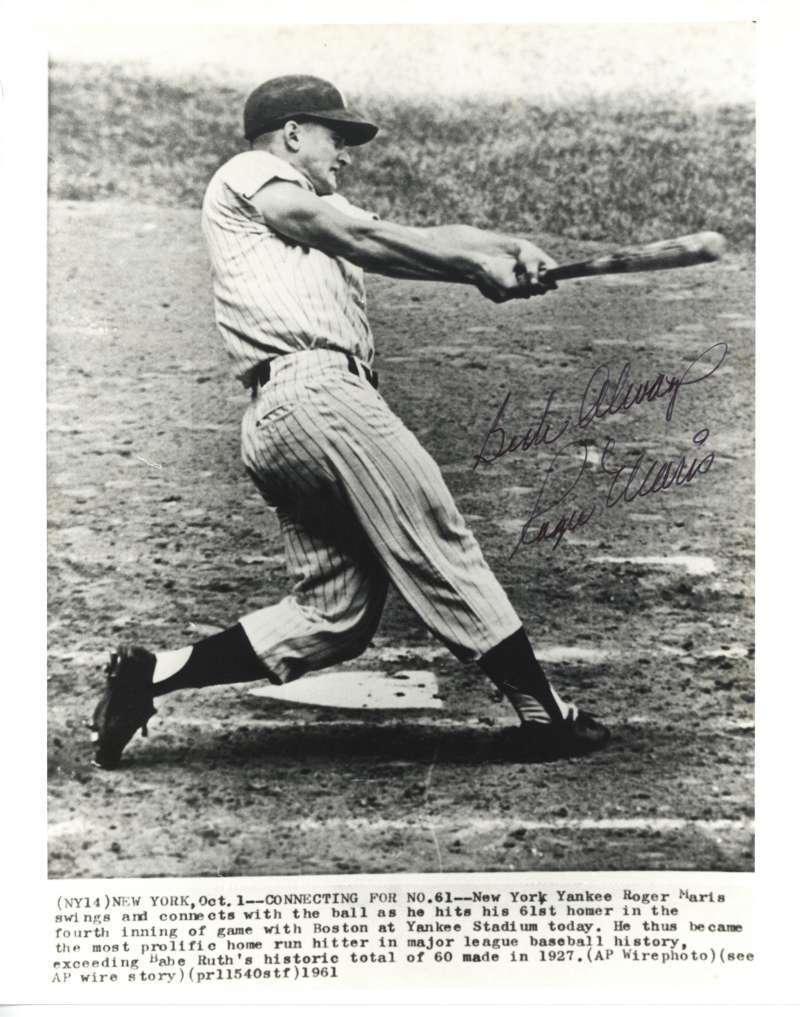

Mantle and Maris engaged in the first of two consecutive home run races in 1960, with Mickey edging out his new teammate for the league lead, 40 to 39. Mantle also knocked in 94 runs, batted .275, and topped the circuit with 119 runs scored. But Maris finished just ahead of Mantle in the league MVP voting, winning the award for the first of two straight times. And, as the season progressed, fans of the team began to develop a strong connection with Mantle. Even though they realized that Maris’s contributions were criticial to the success of the team, the rightfielder began to draw their ire as he challenged Mantle for the league lead in home runs. Since they considered Mickey to be a “true” Yankee, fans of the team rooted for the centerfielder to win the home run crown, and they correspondingly rooted against Maris whenever he stepped to the plate. Mantle subsequently became their hero, something he remained the rest of his career, while they begrudgingy accepted Maris as a necessary evil.

The feelings of the fans towards Mantle and Maris intensified the following year, when the two men waged an epic battle in pursuit of Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record, en route to leading New York to its first world championship since 1958. As the Yankees systematically devastated their opponents on the way to capturing the 1961 A.L. pennant, fans of the team expressed their affection for Mantle more and more, since they felt that, as a “true” Yankee, he should be the one to break Ruth’s record. Maris was cast as an interloper, while Mantle was cheered wildly every time he came to the plate. The fans also believed that Mantle was the better all-around player of the two men, even though Maris was the one who eclipsed Ruth’s record, edging out Mantle for league MVP honors for the second consecutive year in the process. Nevertheless, the numbers posted by Mantle over the course of the campaign would seem to justify the feelings of the fans. He finished second in the league to Maris in home runs, with 54, placed among the league leaders with 128 runs batted in, a .317 batting average, and a .452 on-base percentage, and topped the circuit with 132 runs scored and a .687 slugging percentage.

Even the press, much fonder of the now more gregarious Mantle than the shy and, at times, uncooperative Maris, chose sides. Far more comfortable in the big city than he was earlier in his career, Mantle now spoke freely to the members of the media, fully understanding the types of answers they appreciated, and taking every opportunity to oblige them. Reporters began writing stories that praised Mantle for the courage he displayed as he continued to play through more and more pain as his career wore on. Their articles helped to make Mickey a folk hero of sorts, enabling him to reach iconic-like status, not only in New York, but throughout the entire country. In subsequent seasons, Mantle experienced the kind of popularity enjoyed by few players in the history of the game.

Mantle captured his third MVP trophy in 1962, leading the Yankees to their third straight pennant and second consecutive world championship. Although he missed almost 40 games and compiled only 377 official at-bats, Mantle’s 30 home runs, 89 runs batted in, 96 runs scored, .321 batting average, and league-leading .488 on-base percentage and .605 slugging percentage enabled him to edge out teammate Bobby Richardson for league MVP honors.

Mantle’s 1963 season was cut short by one of the most serious injuries he sustained during his career. Playing in Baltimore, the centerfielder ran into a wire fence in the outfield, breaking his left foot and tearing the cartilage in his left knee. Mantle appeared in only 65 games for the Yankees that year, hitting 15 home runs, driving in 35 runs, and batting .314, in just 172 official at-bats.

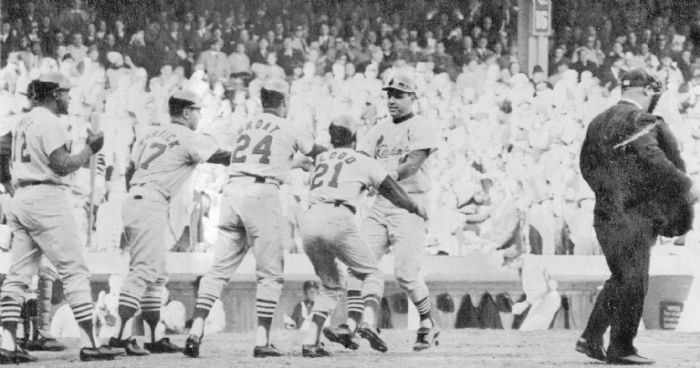

Mantle returned to the team’s everyday starting lineup the following year, and he helped lead the Yankees to their fifth consecutive pennant. Despite limping noticeably and playing in constant pain, Mantle finished among the league leaders with 35 home runs, 111 runs batted in, a .303 batting average, and a .591 slugging percentage. He also led the league with a .426 on-base percentage. The centerfielder finished second to Baltimore’s Brooks Robinson in the league MVP voting. The Yankees lost the World Series to the Cardinals in seven games, but Mantle batted .333 during the Series, drove in eight runs, and hit the final three of his World Series record 18 home runs.

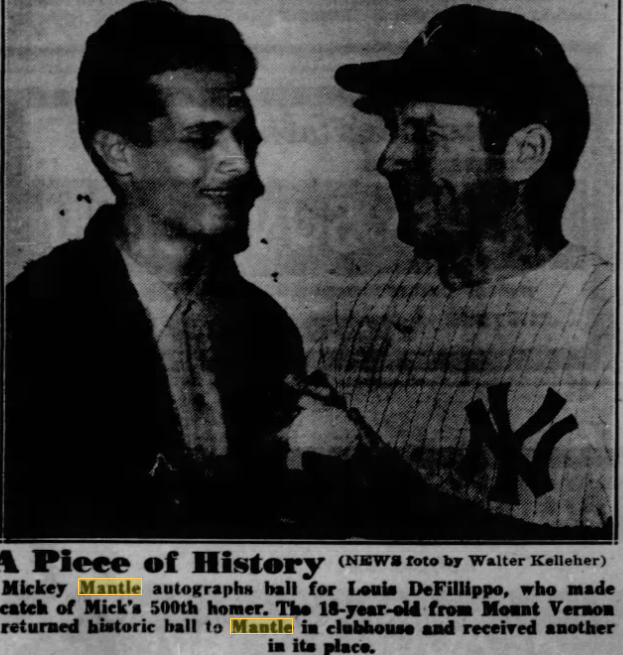

The 1964 campaign was Mantle’s last big offensive year. He missed huge portions of both the 1965 and 1966 seasons with injuries, and he was shifted to first base prior to the start of the 1967 campaign to alleviate the pressure on his aching legs. Playing in great pain until finally retiring in 1968, Mantle never again put up huge offensive numbers. But he remained a productive player whenever his ailing body enabled him to take the field. Mantle ended his career with 536 home runs, 1,509 runs batted in, 1,677 runs scored, 2,415 hits, a .298 batting average, a .423 on-base percentage, and a .557 slugging percentage. His 536 homers were the third most in baseball history at the time of his retirement. Mantle led the league in home runs four times, reaching the 50-homer plateau on two separate occasions. He also topped the circuit in runs scored six times, walks five times, slugging percentage four times, on-base percentage three times, and runs batted in, triples, and batting average one time each. Mantle scored more than 100 runs nine consecutive seasons, from 1953 to 1961. He batted over .300 ten times, was named to the All-Star Team in 16 of his 18 seasons, and won a Gold Glove. In addition to winning three Most Valuable Player Awards, Mantle finished in the top five in the balloting on six other occasions. He helped lead the Yankees to 12 pennants and seven world championships in his 18 years with the team.

As popular as Mantle was with the fans, he was equally beloved by his teammates.

In his book Few And Chosen, former teammate and close friend Whitey Ford refers to Mickey as: “…a superstar who never acted like one. He was a humble man who was kind and friendly to all his teammates, even the rawest rookie. He was idolized by all the other players.”

Ford also says, “Often he played hurt, his knees aching so much he could hardly walk. But he never complained, and he would somehow manage to drag himself onto the field, ignore the pain, and do something spectacular.”

Clete Boyer once expressed his admiration for his teammate by saying, “He is the only baseball player I know who is a bigger hero to his teammates than he is to the fans.”

Roy White, who only played with Mickey during the latter stages of Mantle’s career, talked about the inspiration he was to him: “I was really impressed with the way he played the game, how hard he played the game, and the way he hustled, especially with the bad legs he had. I have a vivid memory of him in DC Stadium, after a doubleheader on a Sunday. It was something like 120 (degrees) down on the floor of the DC Stadium, in July. Looking at him afterwards wrapping the tape off his legs…just sitting there totally exhausted. He had played both games. Mickey would hit a one-hopper over to second base, and he would run all-out to first base. How could you give any less watching a guy like that play the game?”

Opposing players also had a tremendous amount of respect for Mantle because they knew the effort he had to go through late in his career just to be able to take the field to start a game. They also admired his sense of fair play, which prevented him from ever trying to embarrass the opposition. Early in his career, the Yankee front office suggested to Mickey that he do something colorful, such as tip his cap to the fans, whenever he hit a home run. However, Mantle rejected the notion, preferring instead to circle the bases with his head down for fear of embarrassing the opposing team’s pitcher. Explaining his actions, Mantle later said, “After I hit a home run I had a habit of running the bases with my head down. I figured the pitcher already felt bad enough without me showing him up rounding the bases.”

It was Mantle’s humility and courage that made him a hero to opposing players, as well as to his own teammates. Hall of Fame outfielder Carl Yastrzemski once said of Mantle, “If that guy were healthy, he’d hit 80 home runs.”

Former Chicago White Sox second baseman Nellie Fox stated, “On two legs, Mickey Mantle would have been the greatest ballplayer who ever lived.”

Injuries prevented Mantle from ever realizing his full potential. But Mickey’s accomplishments were also diminished somewhat by the frivolous lifestyle he led, which was prompted by his fear of dying young. The men in his family had all passed away at an early age, and Mantle believed the same fate awaited him.

Stating, “I’m not gonna be cheated,” Mantle lived life just as hard as he played baseball. He drank, stayed up until all hours of the night, and was frequently unfaithful to his longtime wife Merlyn, who he married in 1951. Had Mantle taken better care of himself, he likely would have been able to add significantly to the extremely impressive numbers he compiled during his career. And, as Mickey later said, “If I’d known I was gonna live this long, I’d have taken a lot better care of myself.”

Unfortunately, Mantle realized his transgressions too late in life. After being treated for alcoholism at the Betty Ford Clinic in 1994, Mickey discovered that the manner in which he abused his body through the years had left him with inoperable liver cancer. The idol of millions, Mantle displayed dignity and humility in his final days, telling all those fans who had looked up to him as a role model through the years, “This is a role model. Don’t be like me.”

Mickey Mantle died on August 13, 1995, at the age of 63. At his funeral, sportscaster Bob Costas eulogized his lifetime hero by describing him as “a fragile hero to whom we had an emotional attachment so strong and lasting that it defied logic.” Costas added, “In the last year of his life, Mickey Mantle, always so hard on himself, finally came to accept and appreciate the distinction between a role model and a hero. The first, he often was not. The second, he always will be. And, in the end, people got it.”@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

New York Yankees (1951-1968)

Similar: None

Linked: Joe DiMaggio, Willie Mays, Duke Snider, Billy Martin, Roger Maris, Whitey Ford, Bobby Murcer, Kirk Gibson

Best Season, 1956

Mantle was just 24 years old. He won the Triple Crown and the MVP, batting .353 with 52 homers and 130 RBI in one of the best all-around seasons ever. He led with 132 runs scored and a .705 slugging percentage, becoming just the 9th man to top the .700 barrier. His 1.172 OPS was the 20th best in history, and he posted a 1.426 TA. He stole 10 bases in 11 tries. The next season he would increase his batting average and OBP, but his power numbers went down.

Awards and Honors

1956 AL MVP

1956 AL Triple Crown

1957 AL MVP

1962 AL Gold Glove

1962 AL MVP

All-Star Selections

Post-Season Appearances

1951 World Series

1952 World Series

1953 World Series

1955 World Series

1956 World Series

1957 World Series

1958 World Series

1960 World Series

1961 World Series

1962 World Series

1963 World Series

1964 World Series

Where He Played: Center field. Mantle played 262 games at first base, in the final two years of his career. He logged seven games at shortstop and one each at second and third, primarily in the last day or days of the season when Stengel would juggle his lineup… His minor league manager, Harry Craft, said: “He can run, steal bases, throw, hit for average, and hit with power like I’ve never seen. Just don’t put him at shortstop.”

Post-Season Notes

Mantle holds career records for most home runs, runs scored, and RBI in World Series play. He was a World Series champion seven times.

Feats: On May 13, 1955, Mantle hit three homers in one game for the first time in his career. He hit all three into the center field bleachers at Yankee Stadium, each of them “a titanic blast,” according to the New York Times. Mantle hit his first two homers left-handed and the last one right-handed, to become the first batter to hit homers from each side of the plate in American League history. Ironically, Mantle hit the homers with borrowed bats. His first two homers were hit with a bat discarded by teammate Enos Slaughter, and his last homer was hit with a Bill Skowron model.

Notes

Through the Freedom of Information Act, you can download a 29-page FBI report on the hate mail Mantle received while he was a player. Much of it has to do with his playing while others went to war in Korea… On the final day of the 1962 regular season, Yankee manager Ralph Houk batted Mantle in the leadoff spot so he could get enough opportunities to possibly win the batting title. In the midst of the game, after Mickey went 2-for-3 with a walk, Houk removed him since he did not have a chance to overtake Pete Runnels for the title.

Injuries and Explanation for Missed Playing Time

Mantle played and partied like there was no tomorrow, believing he would fail to escape the fate of the men in his family who rarely lived to see 40. He was friend and teammate to Whitey Ford and Billy Martin, often getting into off-the-field troubles. An entire generation of New York baseball fans grew up idolizing the blond-haired, muscular center fielder. In the city the debate raged as to who was better Willie (Mays), Mickey, or the Duke (Snider). Few argued that any player was more talented than Mantle. He battled injuries throughout his career: chronic bone infections, broken foot, shoulder separations, knee problems, torn hamstrings. Despite the setbacks, he played more than 140 games twelve times and led his league in major batting categories on on twenty-five occasions.

Hitting Streaks

16 games (1961)

16 games (1961)

15 games (1961)

15 games (1962)

15 games (1961)

15 games (1962)

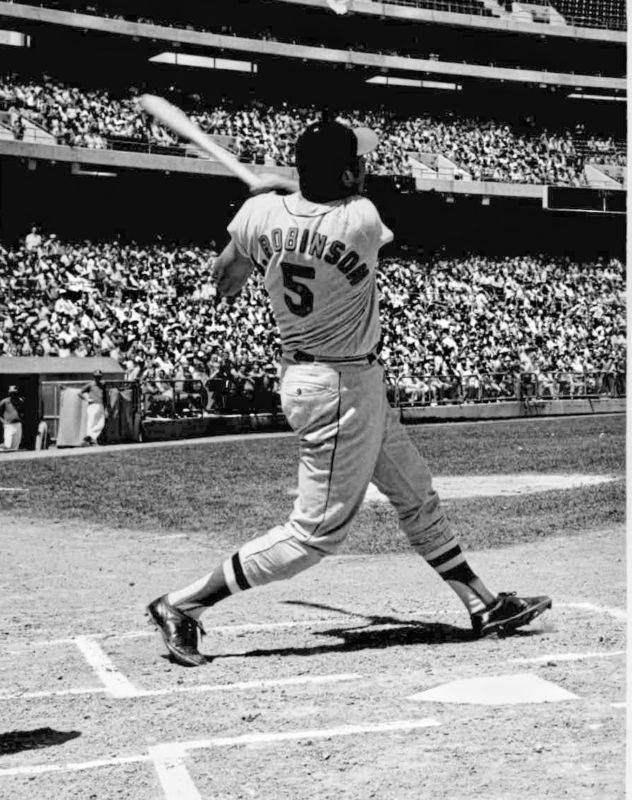

Most Walk-Off Home Runs, Career

Jimmie Foxx……..12

Mickey Mantle……12

Stan Musial……..12

Frank Robinson…..12

Babe Ruth……….12

Tony Perez………11

Dick Allen………10

Harold Baines……10

Reggie Jackson…..10

Mike Schmidt…….10

The Ultimate Autograph Show

Mantle once joked that once he died, if he got to heaven, God wouldn’t let him in because of the wild life he had led. But as he turned to leave, God would say, ‘Before you go, would you sign six dozen baseballs?’

Quotes About Mantle

“He should lead the league in everything. With his combination of speed and power he should win the triple batting crown every year. In fact, he should do anything he wants to do.” Casey Stengel

“There’s one thing he can’t do very well. He can’t throw left-handed. When he goes in for that we’ll have the perfect ballplayer” St. Louis Brown’s Manager Marty Marion when asked if Mickey had a weakness

“That kid can hit balls over buildings.” Casey Stengel on Mickey in 1951

“He’s the best prospect I’ve ever seen.” Branch Rickey in 1951

“If he’d just fling his bat at the ball he’d hit is just as far and maybe he wouldn’t strike out so much and get so mad.” Casey Stengel in 1955, suggesting that Mantle shorten his swing.

“I once invested a dollar when [Mickey] Mantle raffled off a ham. I won, only there was no ham. That was one of the hazards of entering a game of chance, Mickey explained.” Jim Bouton, in Ball Four

“… I dont like the Mantle that refused to sign baseballs in the clubhouse before the games. Everybody else had to sign, but Little Pete forged Mantle’s signature. So there are thousands of baseballs around the country that have been signed not by Mickey Mantle, but by Pete Previte.” Jim Bouton, in Ball Four

Home Run Facts

Many of his home runs were of legendary proportion, such as his blast into the faηade at Yankee Stadium. He hit a home run in Washington that observers estimated went 565 feet.

All-Star Selections

1952 AL

1953 AL

1954 AL

1955 AL

1956 AL

1957 AL

1958 AL

1959 AL

1960 AL

1961 AL

1962 AL

1963 AL

1964 AL

1965 AL

1967 AL

1968 AL

Replaced

Joe DiMaggio

Replaced By

Joe Pepitone

Best Strength as a Player

Power

Largest Weakness as a Player

None

Other Resources & Links