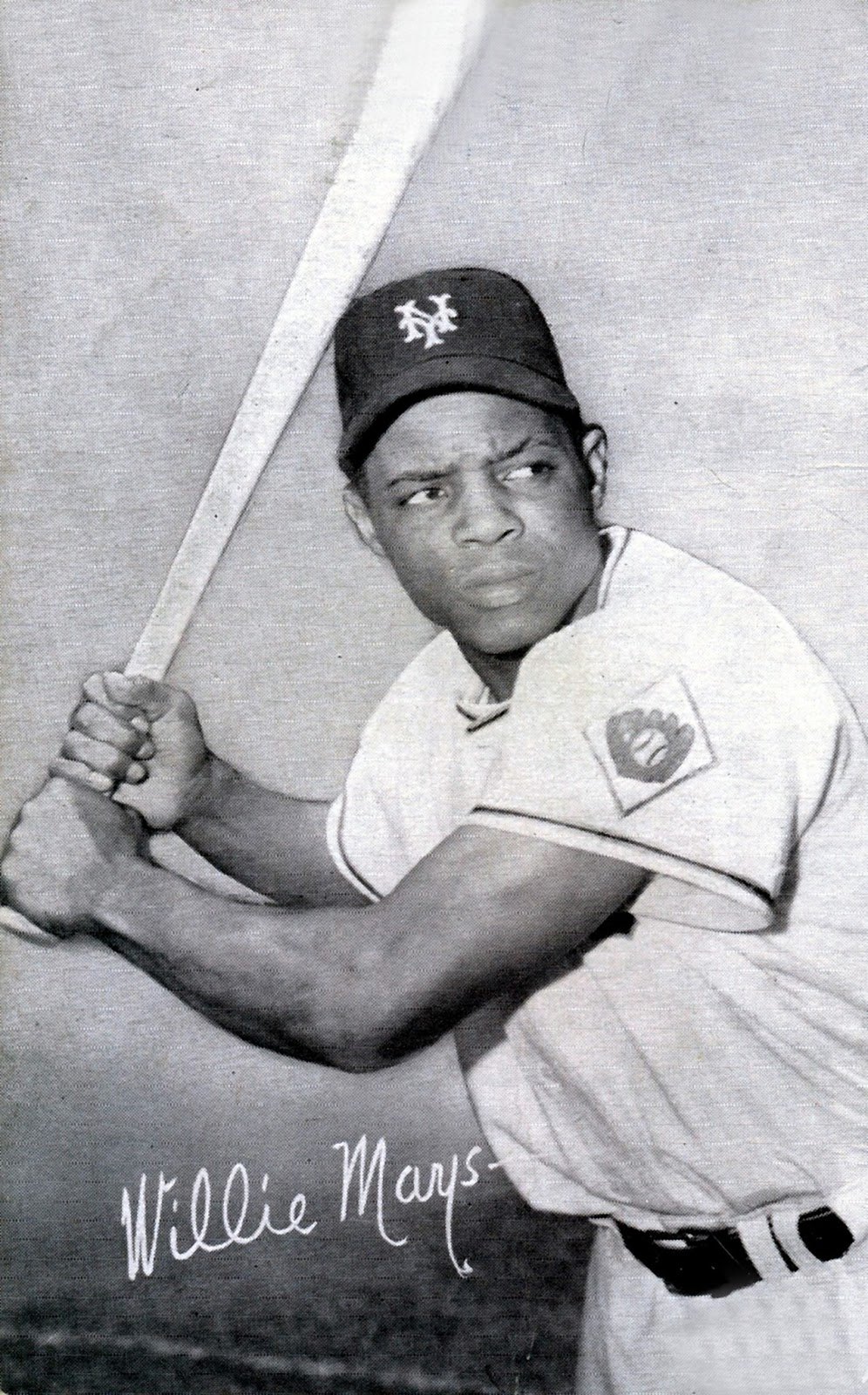

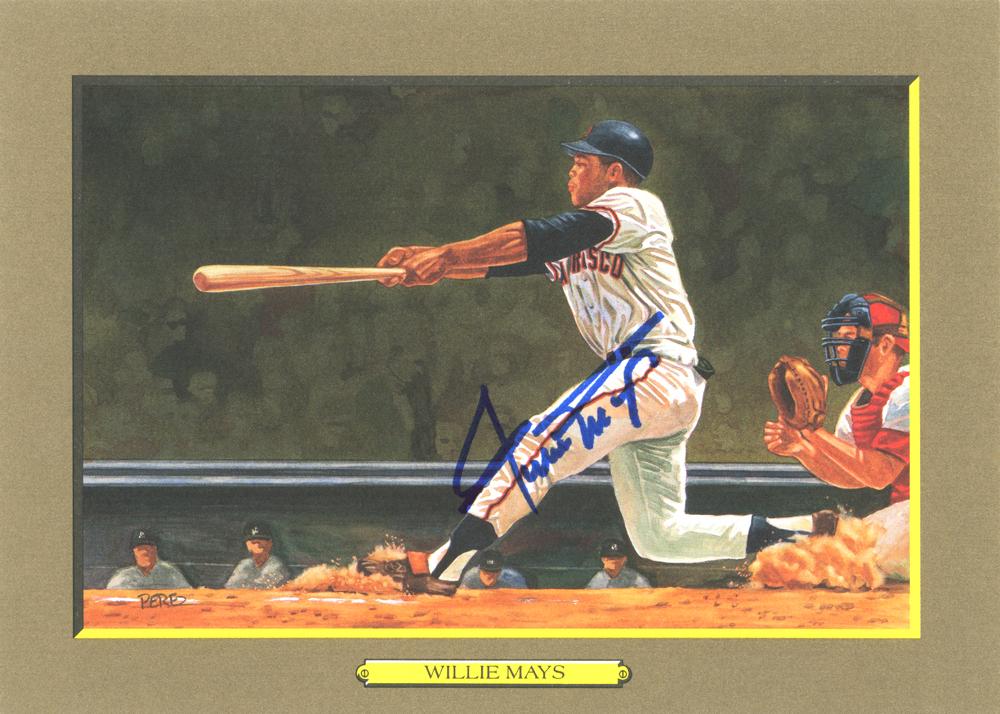

Willie Mays Biography

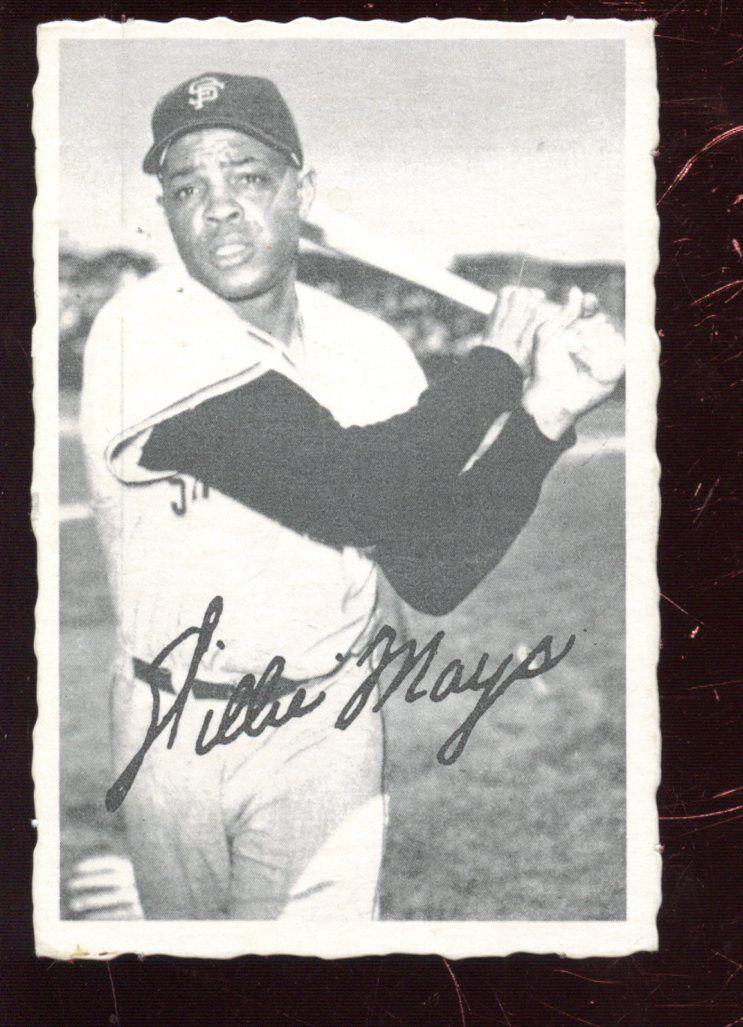

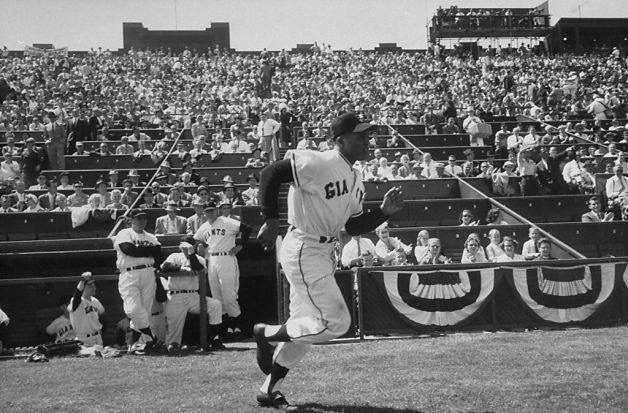

Willie Mays

Position: Centerfielder

Bats: Right • Throws: Right

5-10, 170lb (178cm, 77kg)

Born: May 6, 1931 in Westfield, AL us

High School: Fairfield Industrial HS (Fairfield, AL)

Debut: 1948 (10,389th in major league history)

AL/NL Debut: May 25, 1951

vs. PHI 5 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Last Game: September 9, 1973

vs. MON 2 AB, 0 H, 0 HR, 0 RBI, 0 SB

Hall of Fame: Inducted as Player in 1979. (Voted by BBWAA on 409/432 ballots)

View Willie Mays’s Page at the Baseball Hall of Fame (plaque, photos, videos).

Full Name: Willie Howard Mays

Nicknames: Say Hey Kid

View Player Info from the B-R Bullpen

View Player Bio from the SABR BioProject

Nine Players Who Debuted in 1951

Willie Mays

Mickey Mantle

Roy McMillan

Pete Runnels

Frank Thomas

Johnny Logan

Bob Friend

Rocky Bridges

Gil McDougald

The Willie Mays Teammate Team

C: Tom Haller

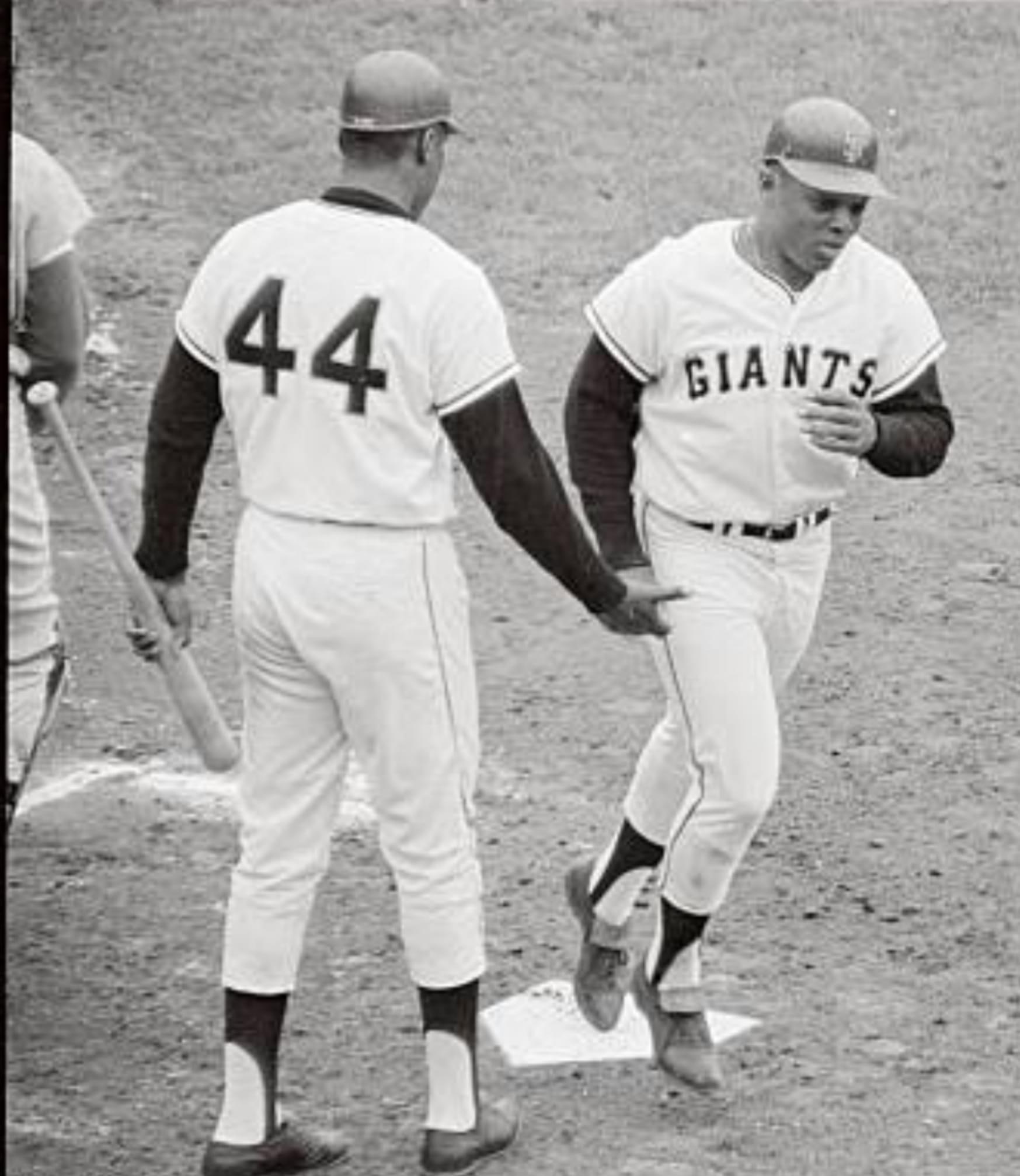

1B: Willie McCovey

2B: Red Schoendienst

3B: Bobby Thomson

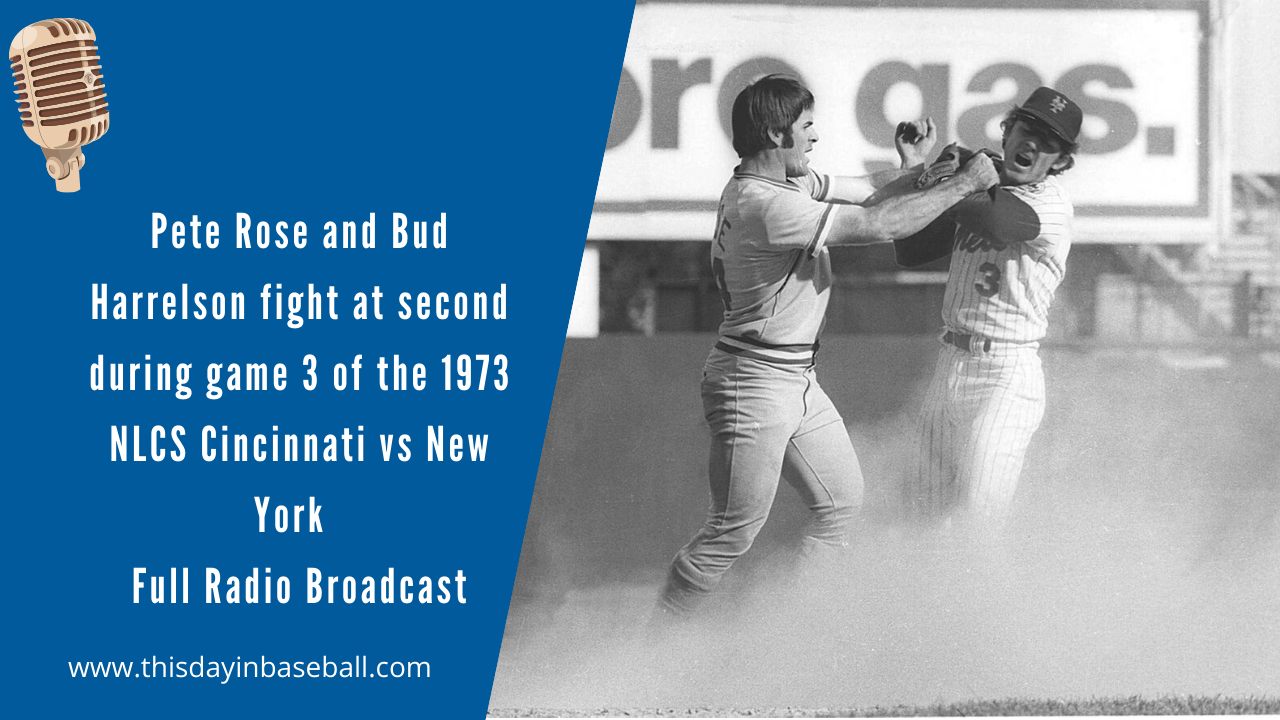

SS: Bud Harrelson

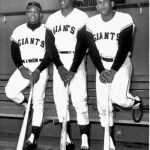

LF: Monte Irvin

CF: Garry Maddox

RF: Bobby Bonds

SP: Juan Marichal

SP: Tom Seaver

SP: Sal Maglie

SP: Gaylord Perry

SP: Jerry Koosman

RP: Hoyt Wilhelm

RP: Tug McGraw

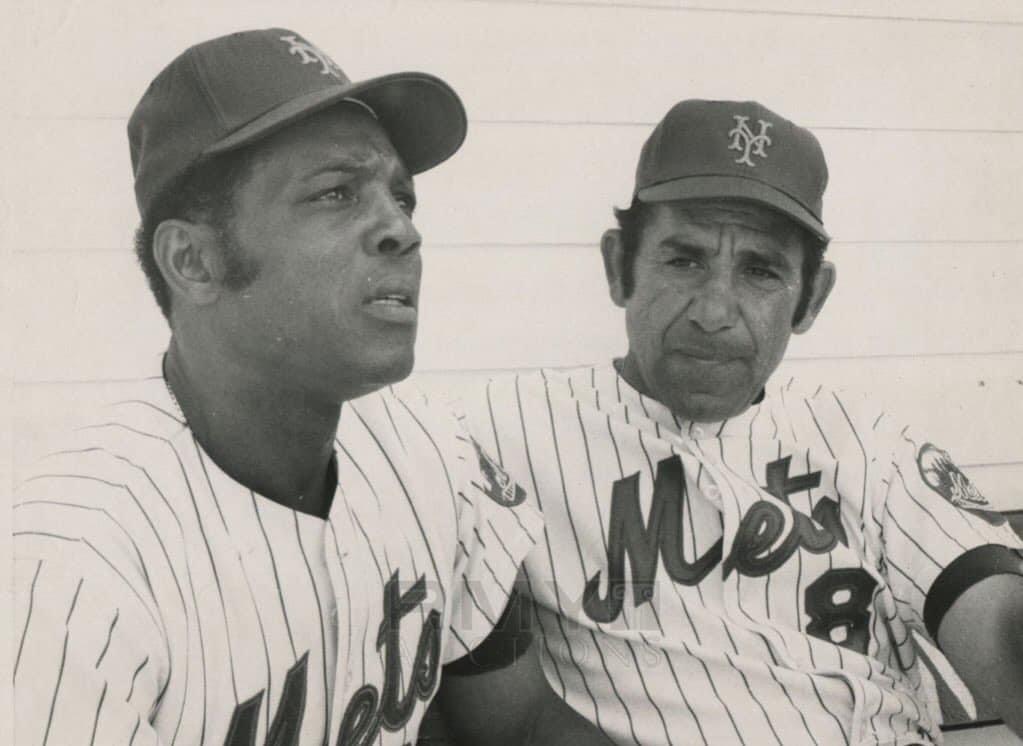

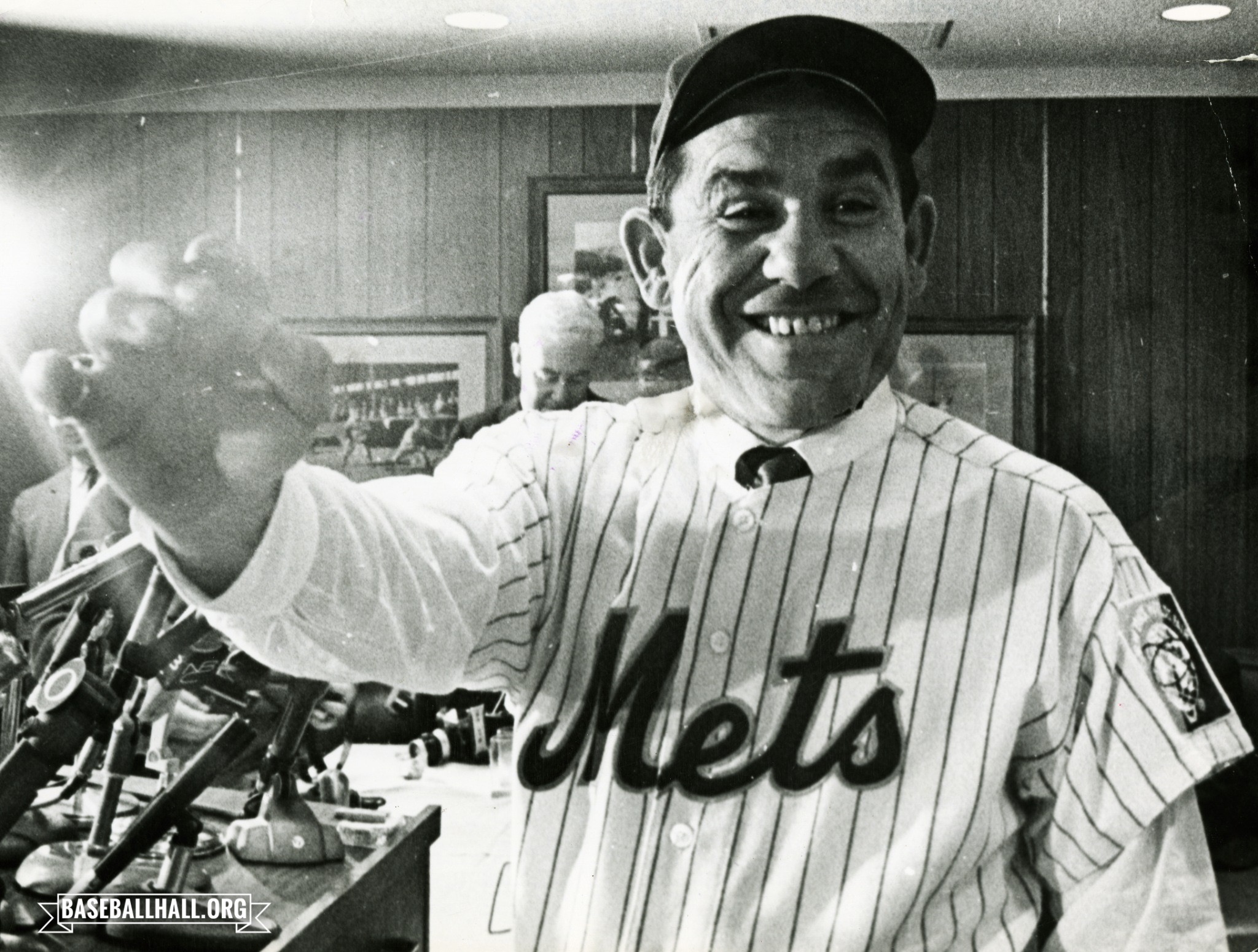

M: Yogi Berra

Notable Events and Chronology for Willie Mays Career

Willie Mays Biography

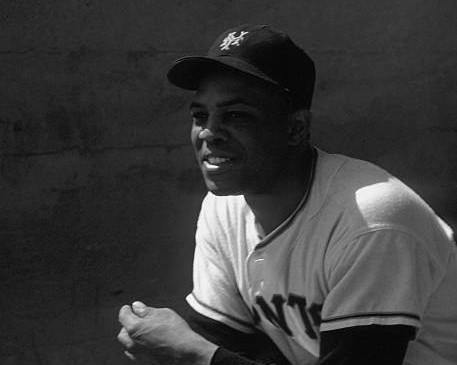

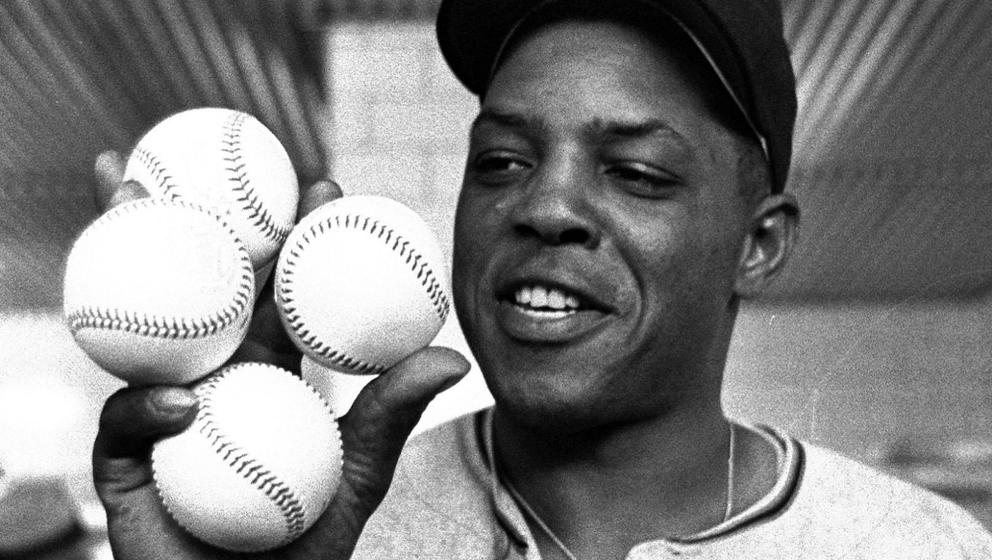

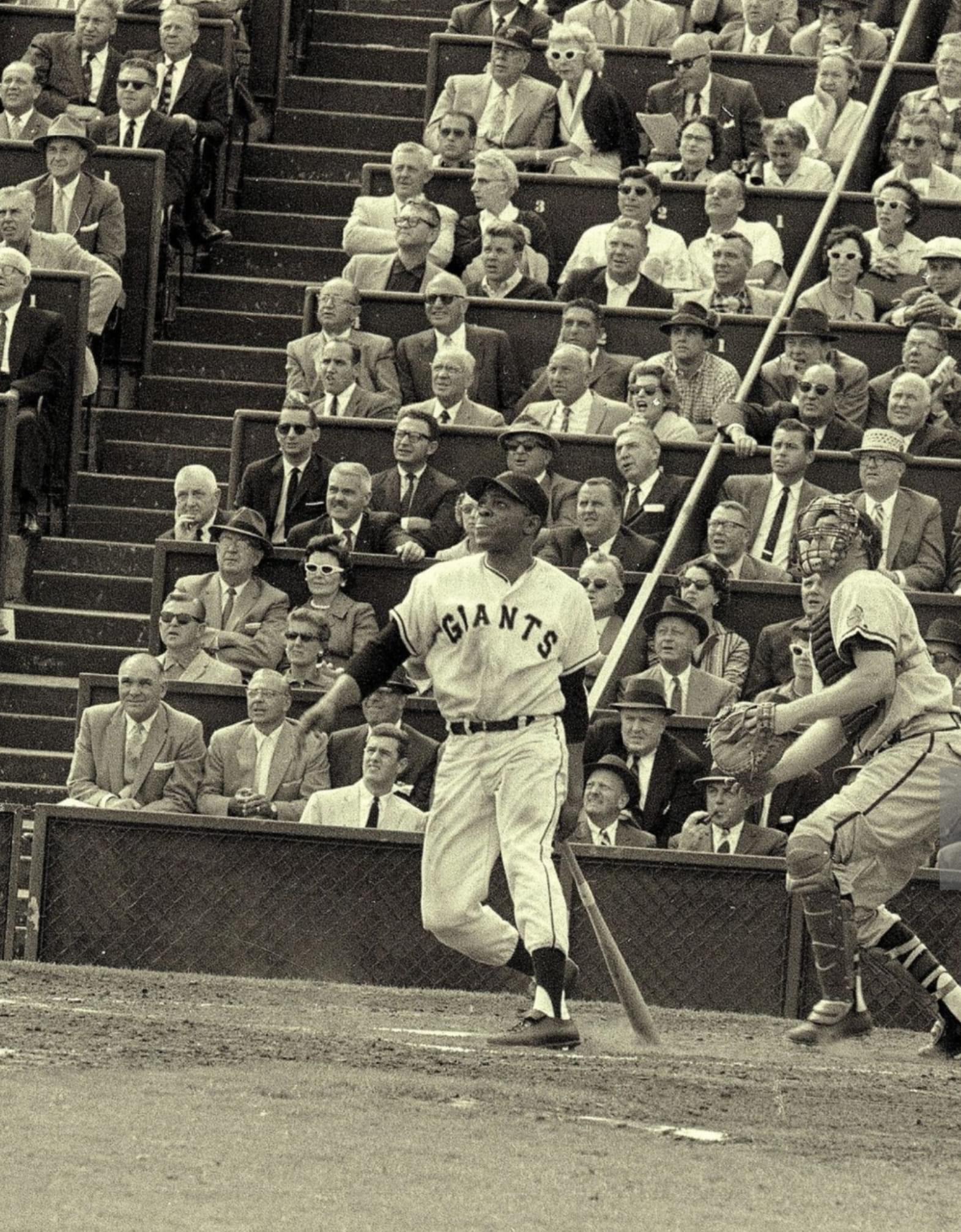

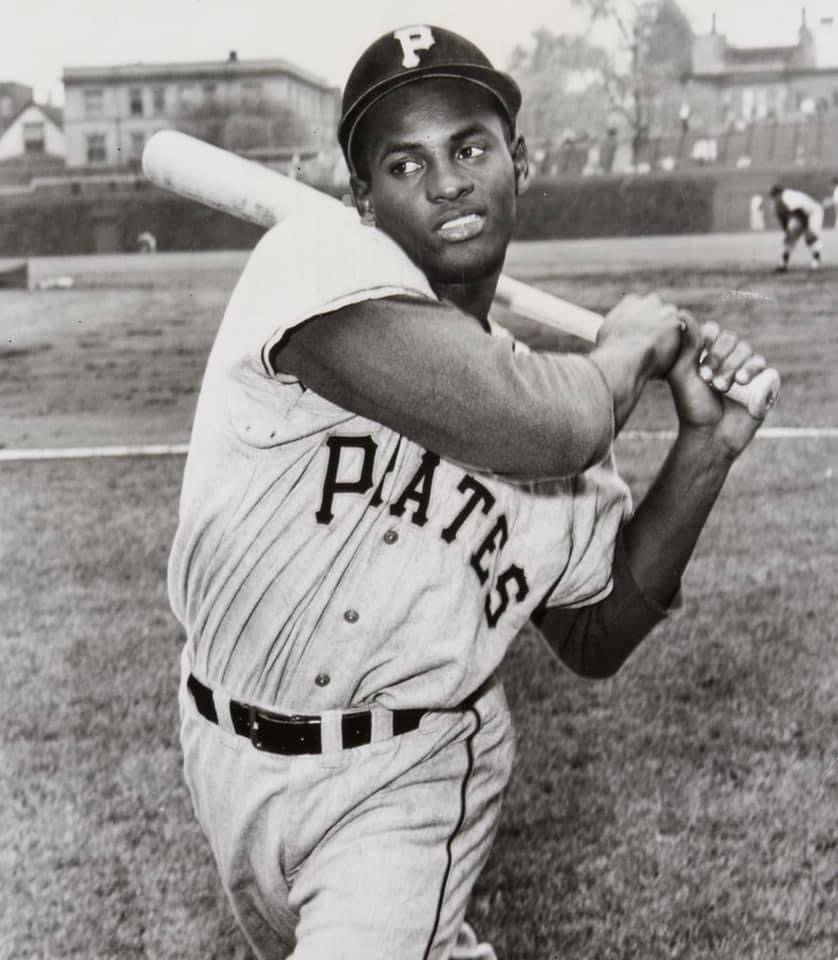

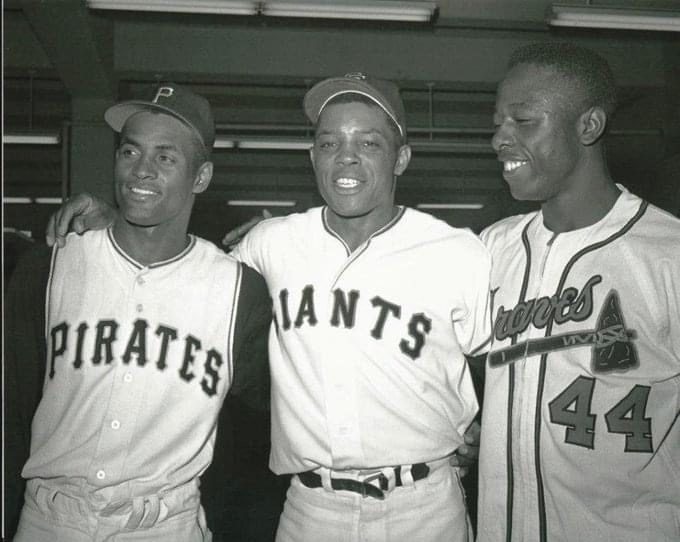

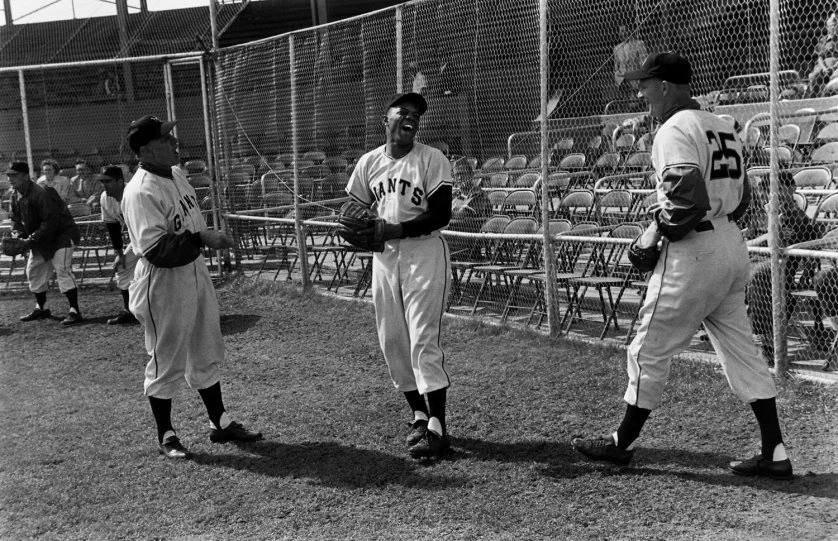

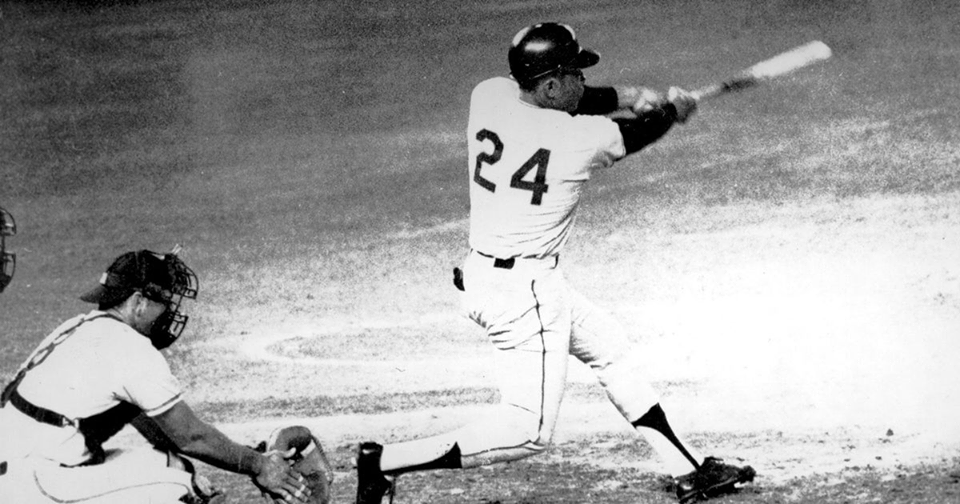

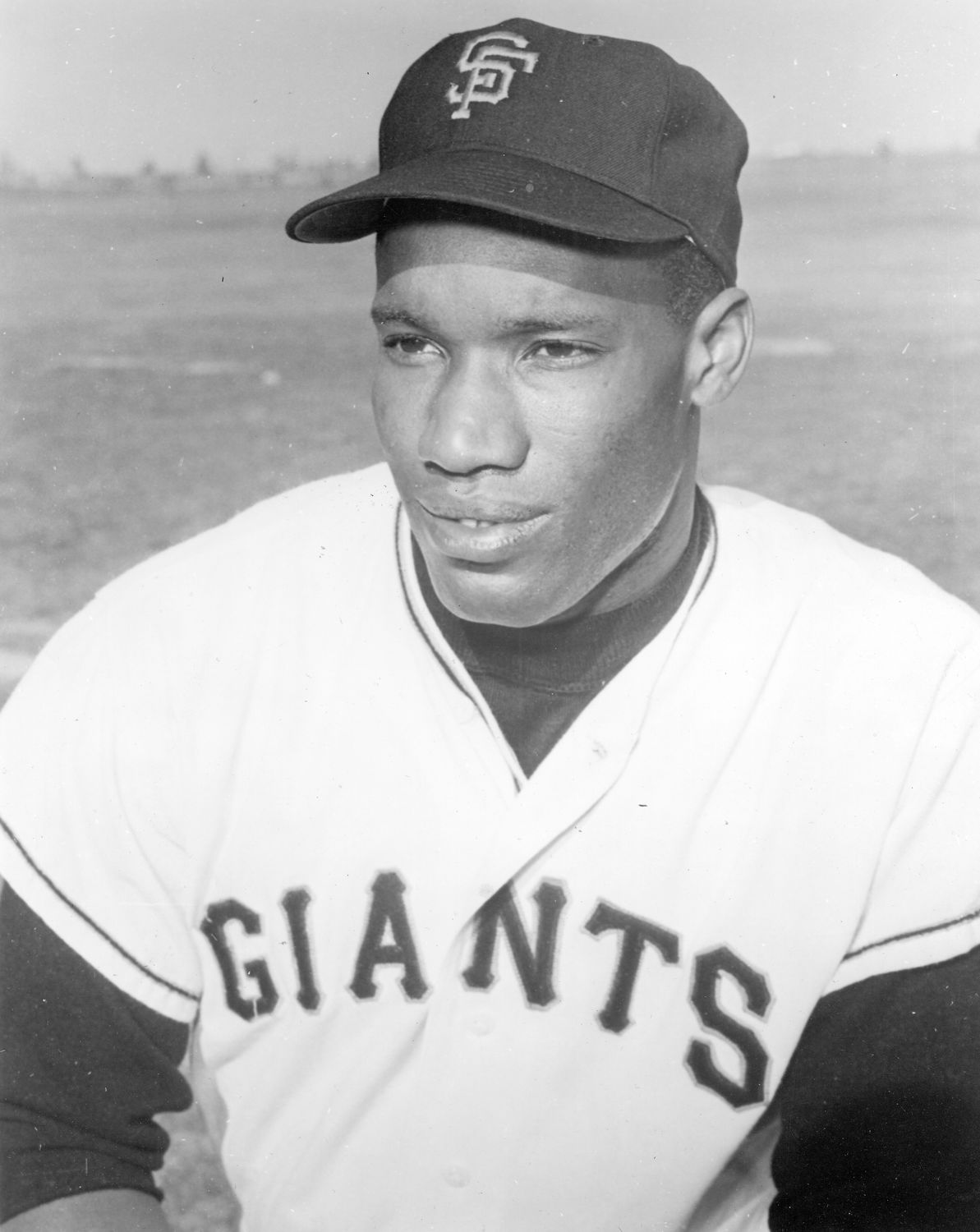

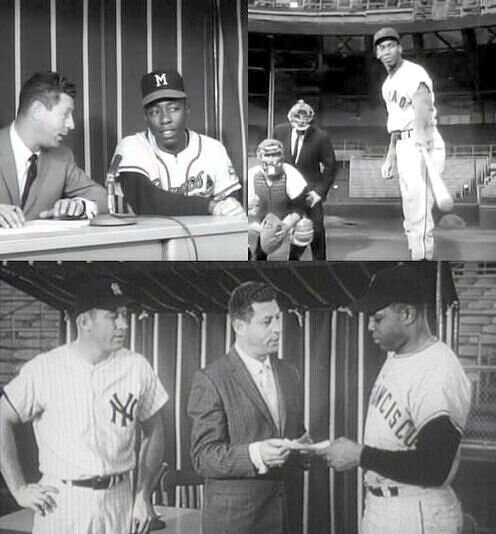

In the minds of many baseball experts, Willie Mays is the greatest all-around player the game has ever produced. The “Say Hey Kid” excelled in every facet of the game, and he did so with a joyful abandon that made him one of the most popular sports figures of his era. Among baseball’s immortals, few can boast offensive totals that are as balanced as those compiled by Mays; he is the only player in history to finish his career with over 600 home runs, 3,000 hits, 1,900 RBIs, 2,000 runs, and 300 stolen bases. Fewer still could match Mays’ bravura in the outfield, where his blinding speed and howitzer arm earned him 12 Gold Gloves and 7,095 putouts – both records among outfielders. Mays broke into the big leagues with a Rookie of the Year campaign in 1951, and in the 22 brilliant years that followed, he collected two MVP trophies, a World Series ring, and a record 24 All Star Game appearances. Fans and fellow players were drawn to Mays not only by his breathtaking ability, but also by the boyish exuberance he exuded on the playing field, a winning and winsome charisma that made him, in the words of manager Leo Durocher, “a super superstar.”

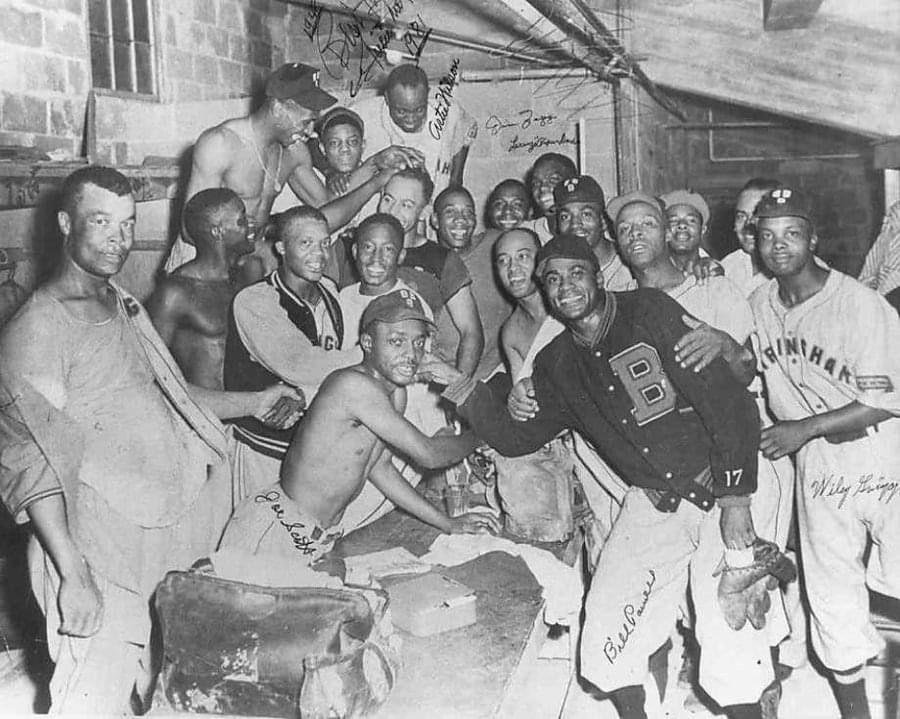

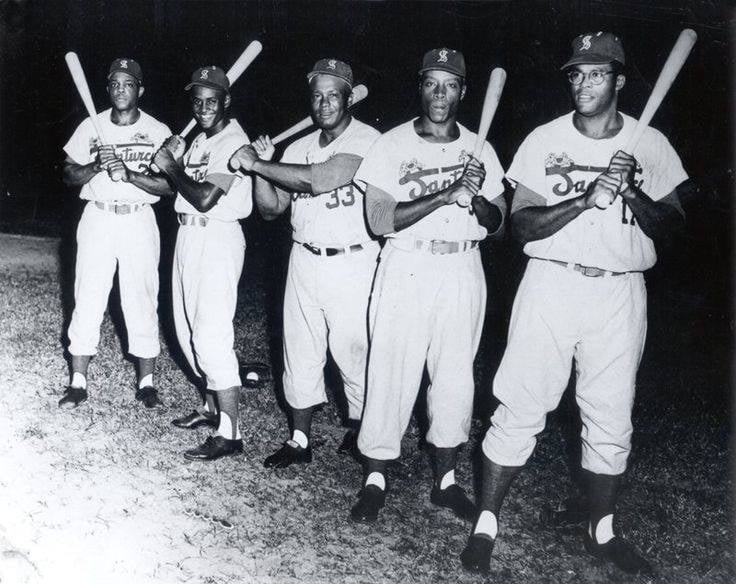

The path to that superstardom began in the small town of Westfield, Alabama, where Mays was born on May 6, 1931. There are reports that the infant Willie slept with a ball in his crib, and that he learned to walk by toddling after a baseball. Such stories are probably apocryphal, but they go a long way toward explaining the preternatural gift for the game that Mays displayed as a teenager. Though he starred in football and basketball, his local high school lacked a baseball team, so Mays picked up with a local Negro minor league team. Mays’ spectacular play gradually caught the attention of Piper Davis, manager of the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League. Davis took the 16-year-old prodigy under his wing and added him to the big team’s roster. Mays’ father, himself a semi-pro ballplayer in his youth, insisted that Willie finish high school before committing to baseball full-time, so he was allowed to play only home games on the weekends. Even at that young age and in limited playing time, Mays made a big impression on his elders. Davis remarked that he “[n]ever saw anybody throw a ball from the outfield like him, or get rid of it so fast.” After graduating from high school, Mays proved to be no slouch in the batter’s box either, batting .311 and .330 in 1949 and 1950, respectively, while also posting exceptional power numbers.

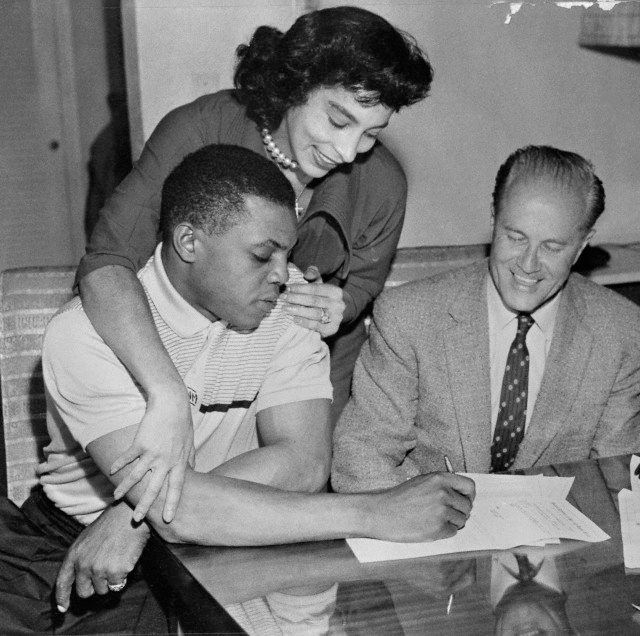

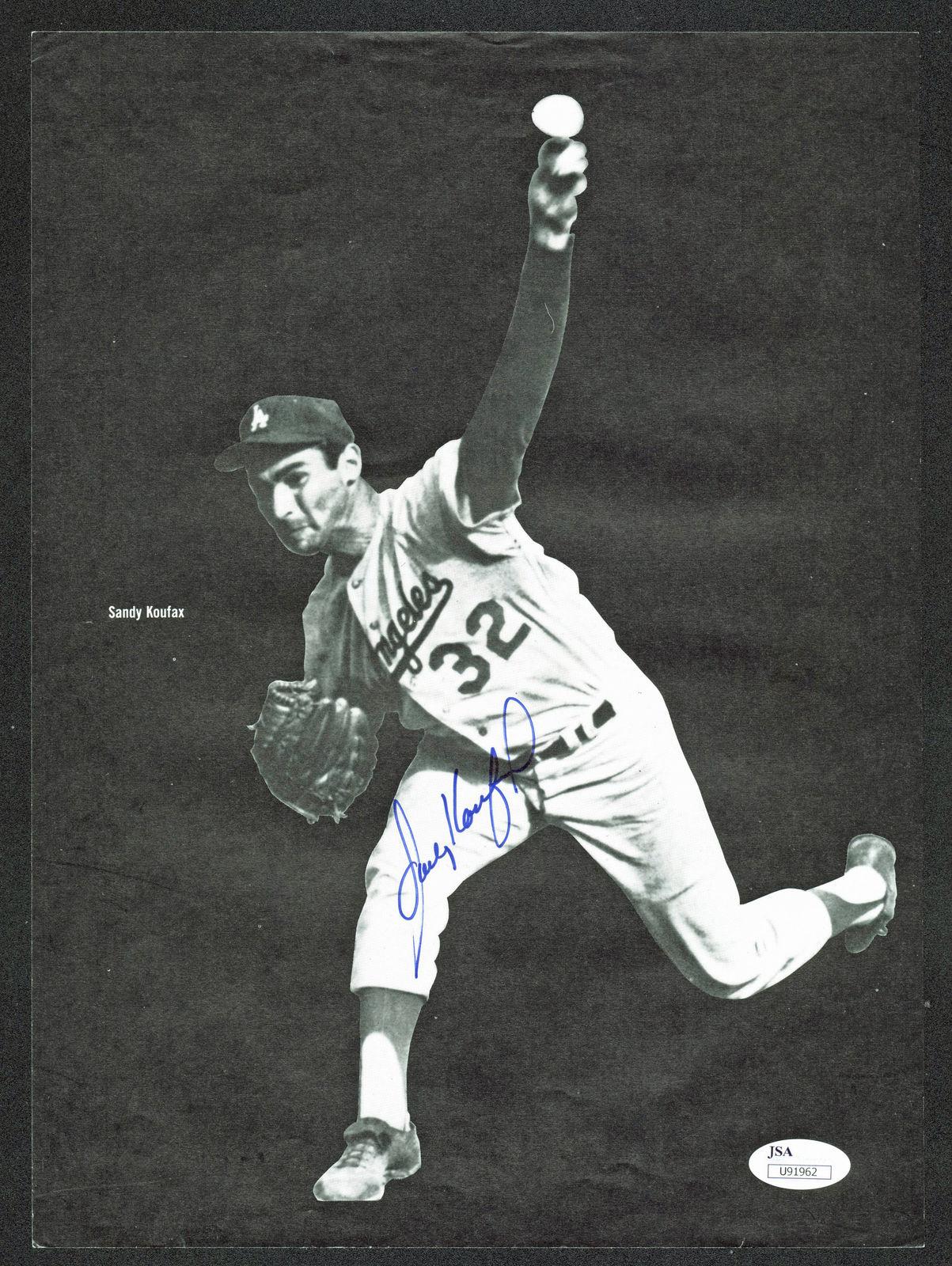

As the Negro Leagues waned into obsolescence in the aftermath of Jackie Robinson’s breaking into the major leagues, Mays was scouted by a number of big league clubs. However, most were put off by his purported inability to handle the curveball. New York Giants scout Eddie Montague, though, was floored by the potential he saw in Mays, who he suggested to Giants manager Leo Durocher was the greatest young player he had ever seen. On the strength of Montague’s recommendation, the Giants signed Mays for $4,000 and shipped him to their Class B affiliate in Trenton, New Jersey. After competing against greats such as Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson in the Negro Leagues, Mays found the competition in B-level ball to be no competition at all, batting .353 with 108 hits in 81 games in 1950. The young slugger really came into his own when he was promoted to the AAA Minneapolis Millers the following year, hitting a blistering .477 with eight home runs in his first 35 games to go along with his stellar defense.

With Mays tearing up minor league pitching and making the spectacular look routine in the outfield, the buzz surrounding the phenom became too great for the Giants to ignore. Durocher in particular was anxious to bring Mays up to the big league club immediately, but Giants management, fearing the 20-year-old might be drafted into military service at any moment, demurred. However, with the Giants floundering in fifth place in late May, the young sparkplug was brought up to give the ball club a much needed shot in the arm. Mays joined the team on the road in Philadelphia, where Durocher immediately installed him as the team’s starting center fielder.

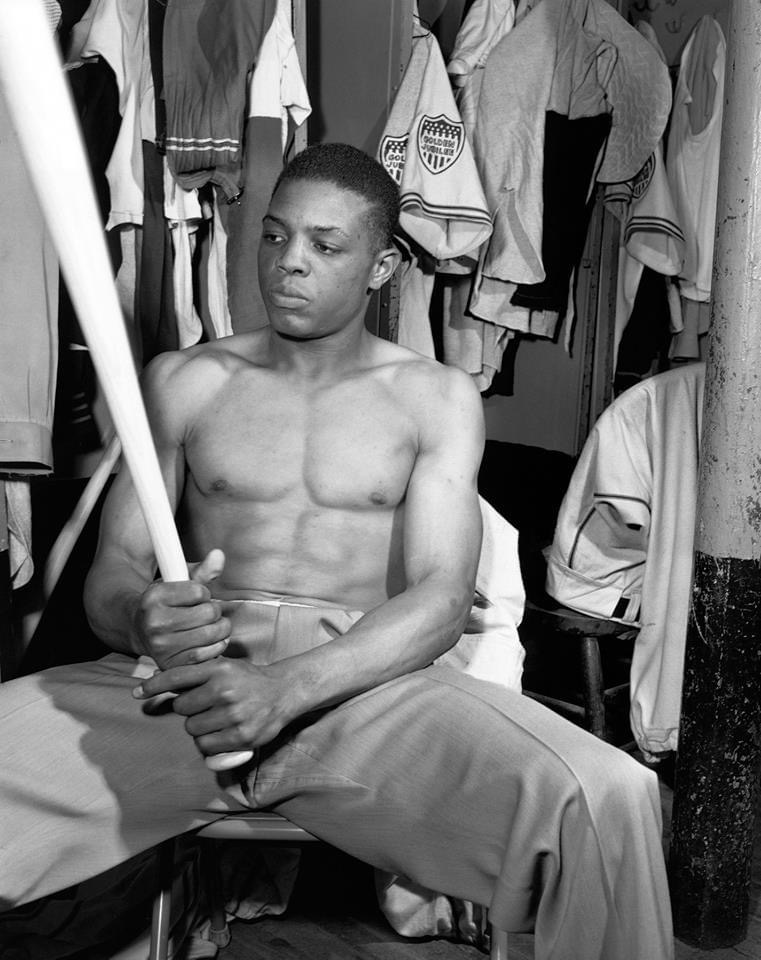

Mays, for whom success in baseball had always come easily, found the transition to the varsity difficult; he went 0-for-12 to start his career, though the Giants won all three games in his first series. Willie finally scored his first hit when the club returned to the Polo Grounds, blasting a towering home run off ace starter and future Hall of Famer Warren Spahn. His struggles continued after that blow, however, as he went 0 for his next 13. After taking an 0-for-4 collar in one game, the pressure finally got to Mays, who broke into tears in front of his locker. In a move that may have saved Mays’ career, Durocher assured the youngster that Mays would be his centerfielder as long as he was manager.

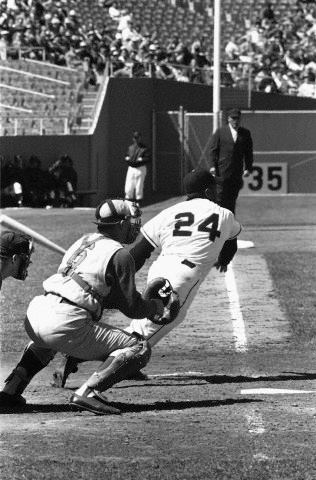

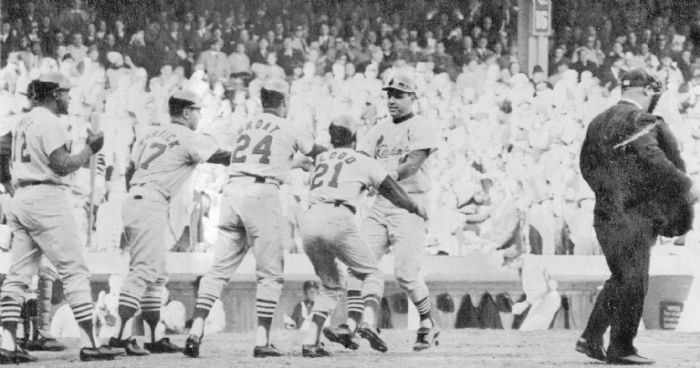

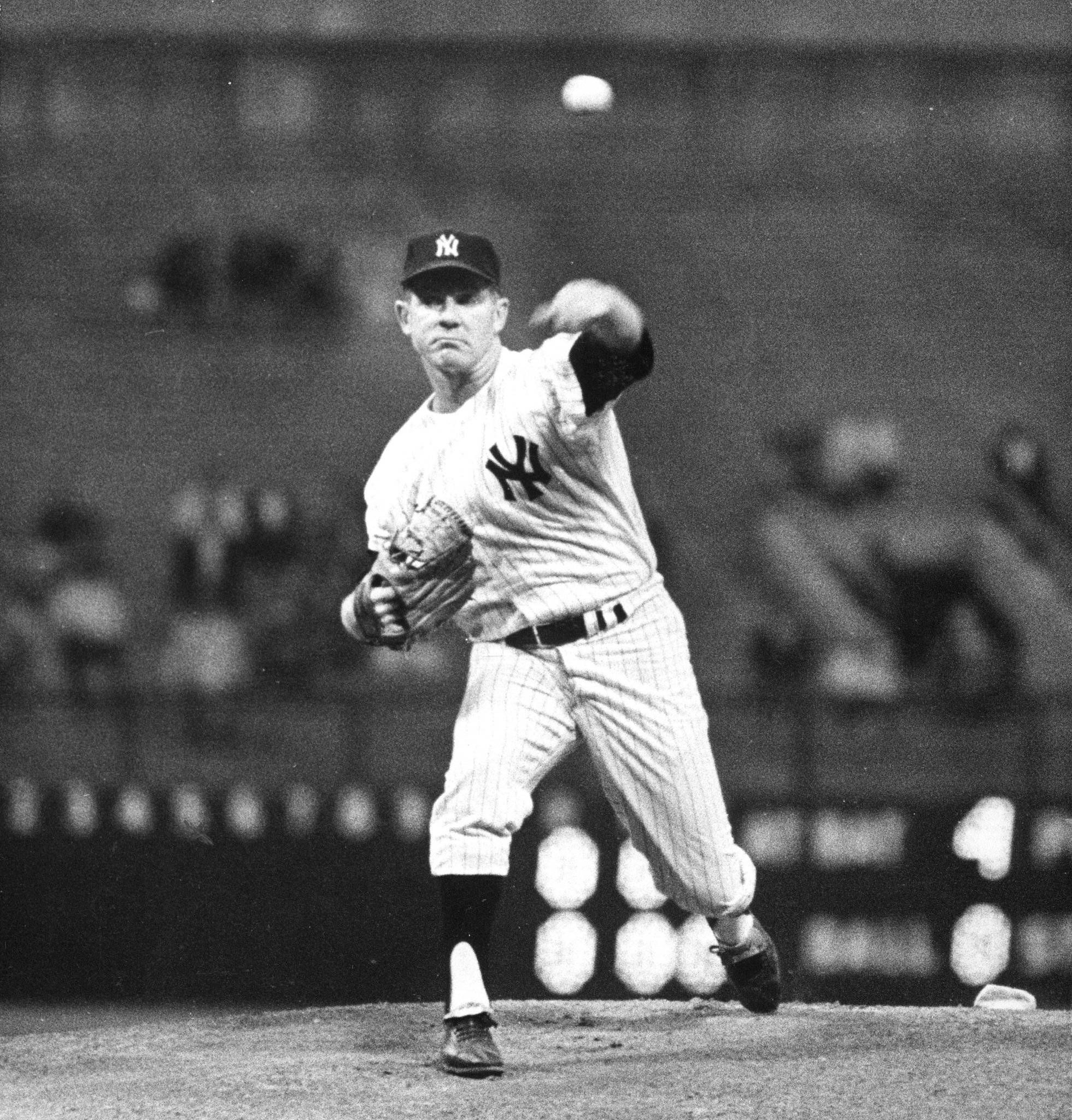

Buoyed by this reassurance, Mays settled down and raised his anemic .040 average to a more robust .274 by season’s end, while swatting 20 homers in 121 games. Over the course of those 121 games, Mays and his Giants pulled off one of the most improbable comebacks in modern sports history, going 37-7 down the stretch to overcome a 13.5-game deficit and overtake the archrival Brooklyn Dodgers to win the National League pennant. (A visibly anxious Mays was in the on-deck circle when Bobby Thomson hit his famous “shot heard ‘round the world”.) Mays struggled in the World Series that year (playing against another rookie outfielder named Mickey Mantle) as the Giants fell to the Yankees in six games. Nevertheless, he was named Rookie of the Year for his accomplishments during the regular season.

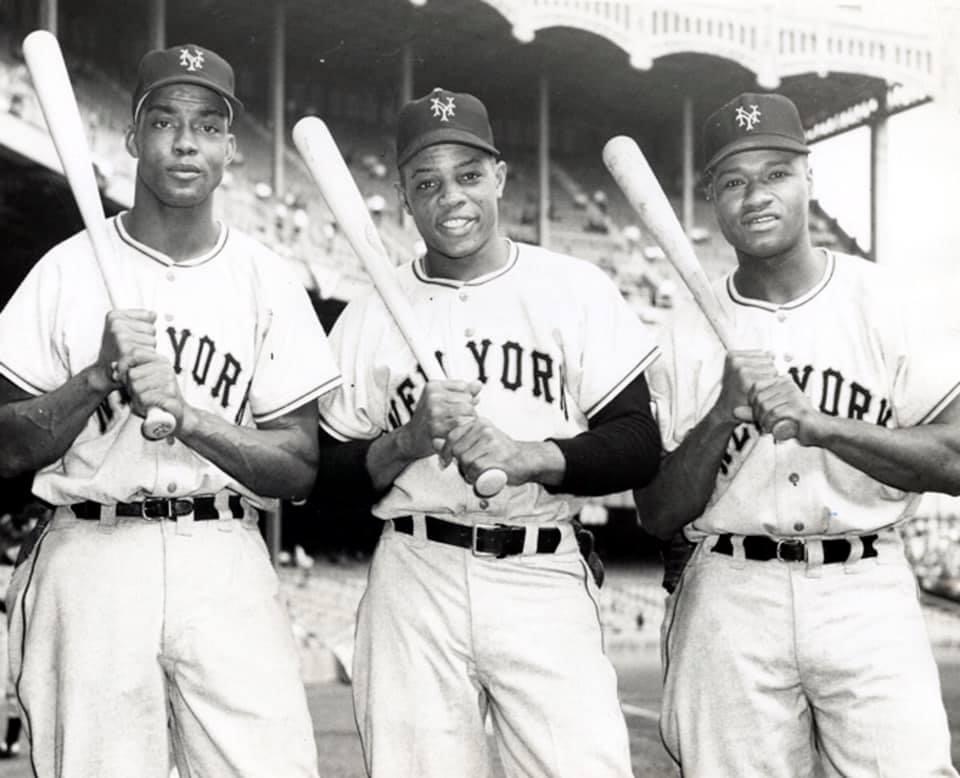

When he was called up to the majors, the Giants installed the hayseed Mays into an apartment in cosmopolitan Harlem, and assigned fellow outfielder and future Hall of Famer Monte Irvin to act as his informal chaperone. The charming and ebullient Mays soon became a fixture in the community and a darling among the famously demanding New York media. The image of a sinewy, short-sleeved Mays playing stickball with neighborhood children has become one of the most enduring ones of 1950’s Americana. Such sessions were not staged; not only did Mays actively and frequently participate in street games, he often took his pint-sized teammates out for sodas afterward.

Mays was uprooted from his halcyon life in Harlem, and the Giants’ worst fears were realized when he was drafted by the United States Army in 1952. He saw limited duty, playing over 180 exhibition games during his two years in the service, while missing 266 games with the big league club. His absence was keenly felt by his teammates. When Mays played his last game before reporting for duty early in the 1952 season, the Giants were in first place. However, they eventually lost the pennant to the Brooklyn Dodgers that year. While Mays missed the entire 1953 season, his Giants limped to a 70-84 record and fifth place.

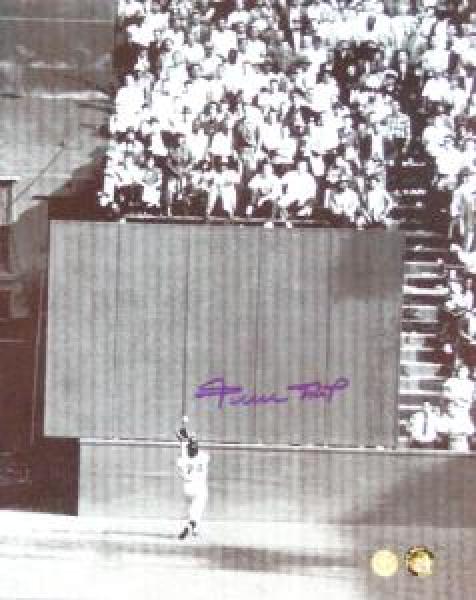

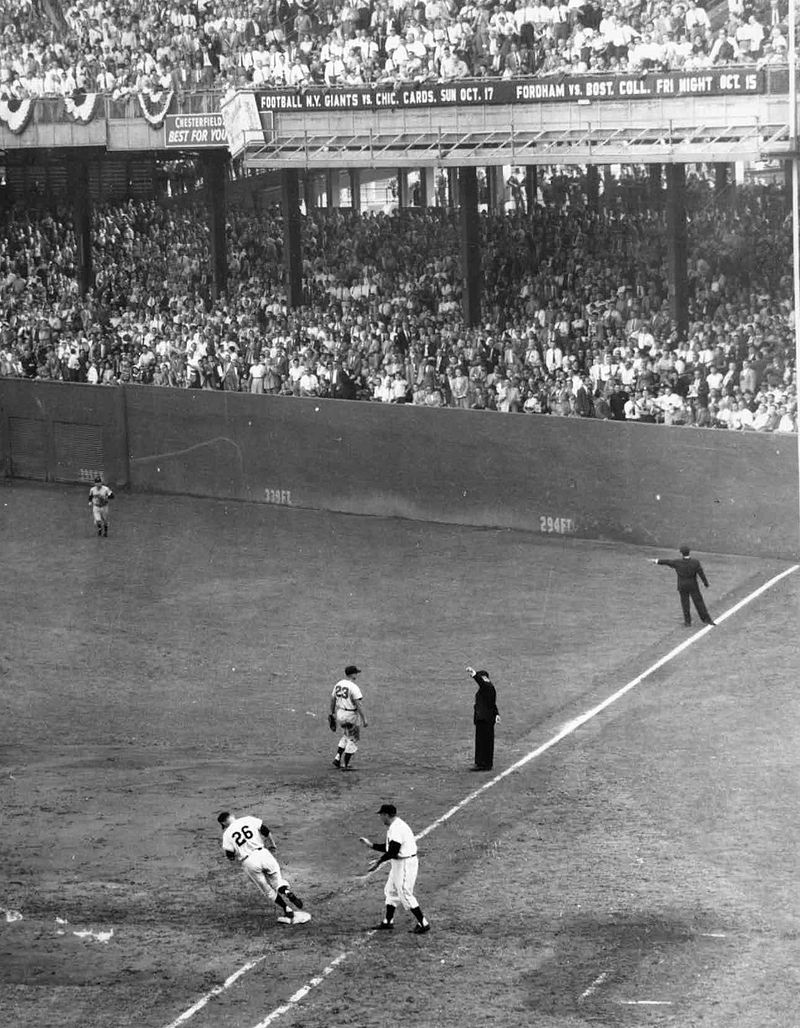

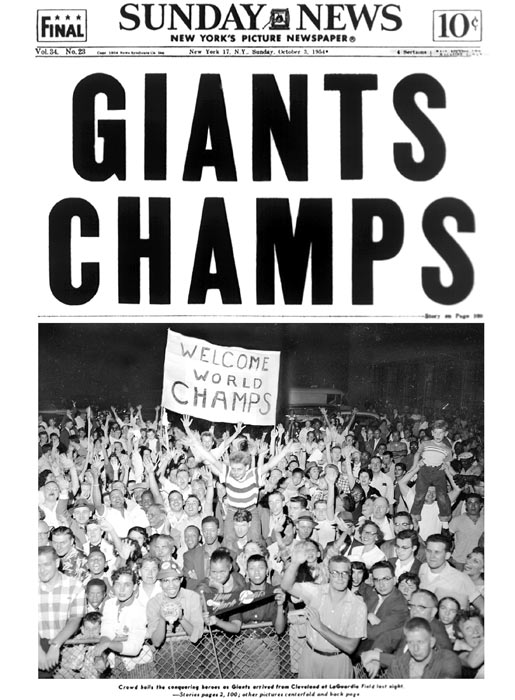

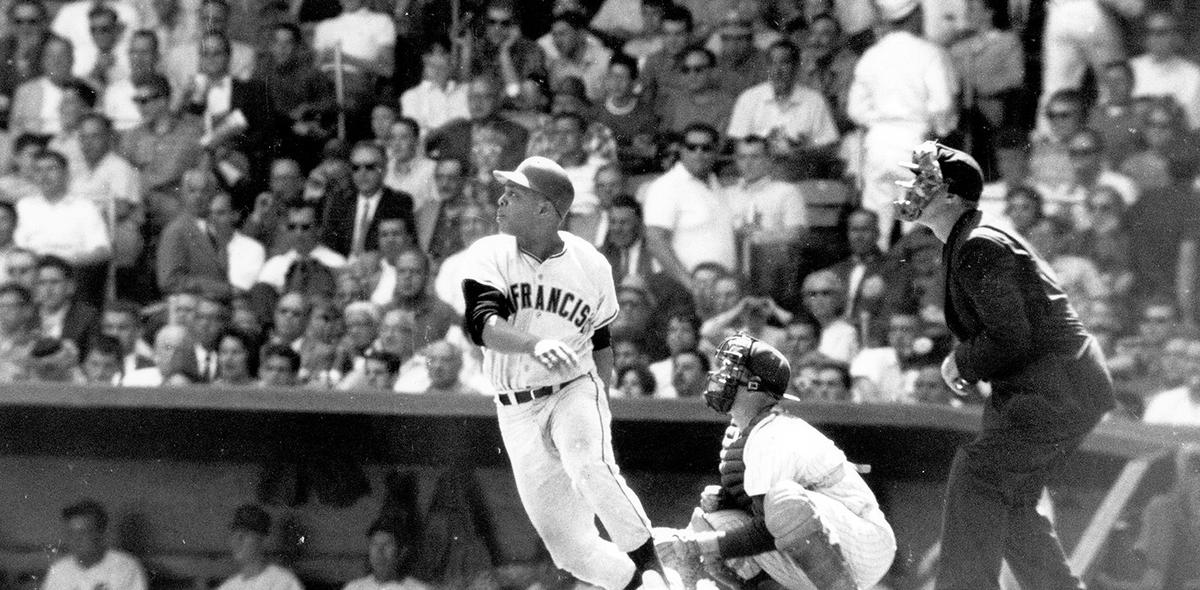

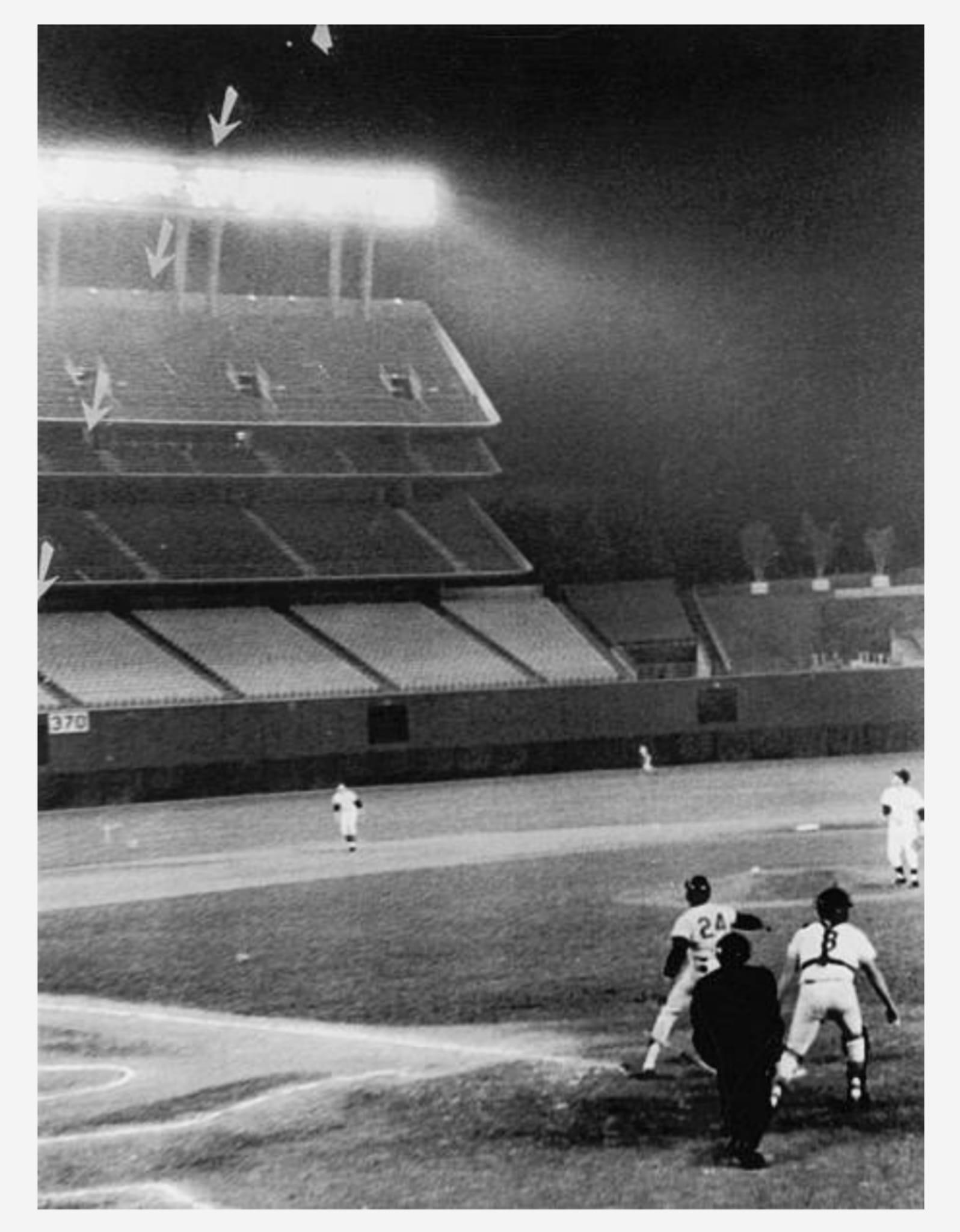

Mays reversed the Giants’ postseason fortunes and delivered on his superstar promise when he returned for the 1954 season. A slightly bulkier Mays dominated the National League that year, clubbing 41 home runs and capturing the NL batting title with a .345 average. More importantly, Mays led his Giants to 97 wins and a return to the World Series. Mays’ offensive prowess earned him his first All-Star nod, along with the first of his two MVP awards, but it was the spectacular play he made in the outfield during the Fall Classic that elevated him to legendary status.

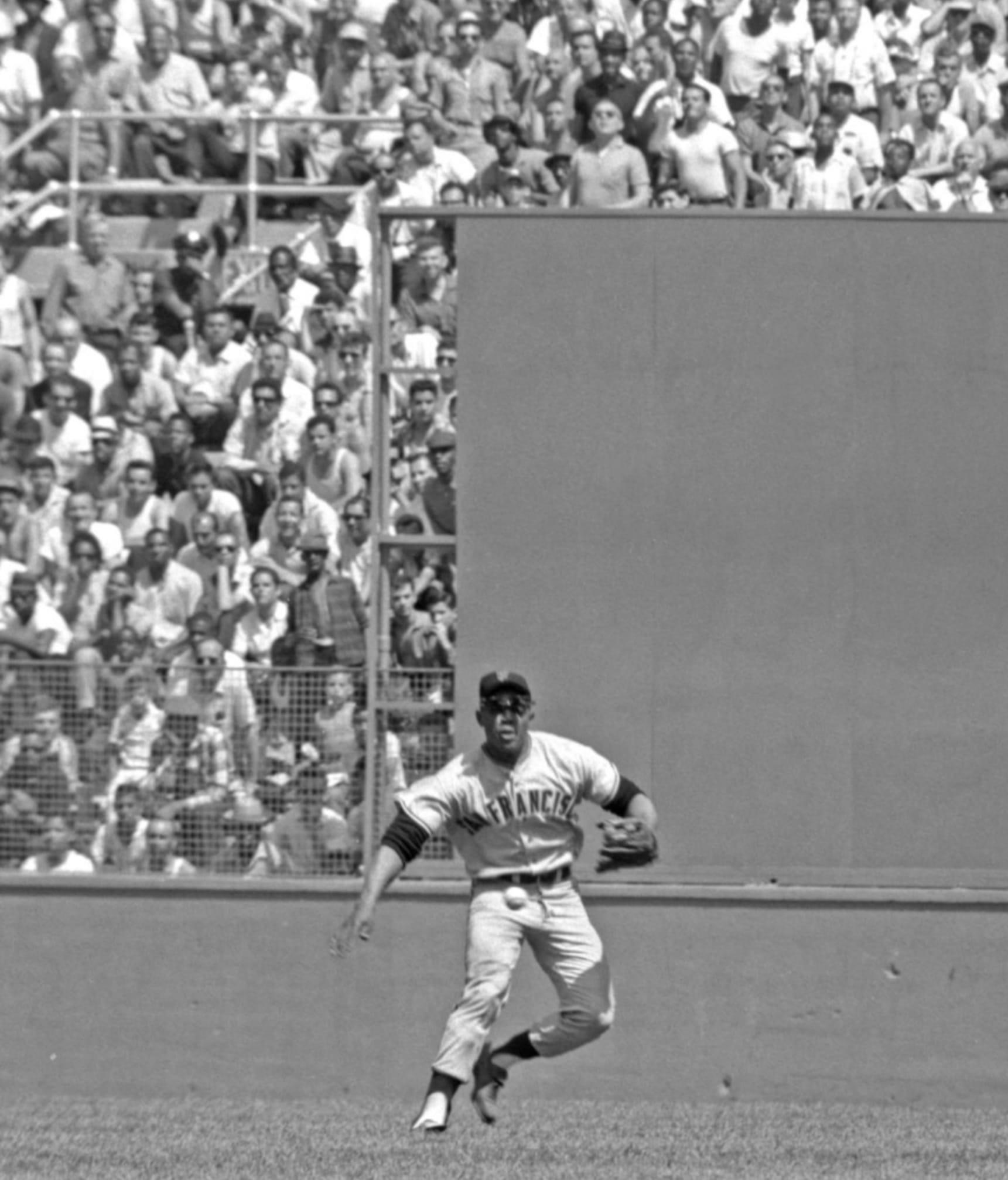

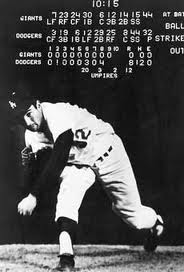

The heavily favored Cleveland Indians jumped out to a 2-0 lead in the first inning of Game 1 at the Polo Grounds, but the Giants rallied to tie the score in the third. The score remained the same going into the top of the eighth inning, when a walk and single put the Indians in striking distance of home plate. Formidable slugger Vic Wertz then hit a towering 440-foot drive to center field; as the ball plummeted earthward, it seemed only a question of how many runs the Indians could score on the play. Mays, tracking the ball perfectly, sprinted to the warning track and made what has become known simply as “The Catch”, a breathtaking, over-the-shoulder grab that saved the game and shifted the momentum of the series in favor of the Giants. The thing that was lost in much of the subsequent analysis of Mays’ amazing feat was “The Throw”; as the crowd roared its ecstatic disbelief, Mays spun and fired a rocket towards the infield, preventing Cleveland outfielder Larry Doby from tagging up and scoring the go-ahead run. Mays later scored the winning run himself in the 10th inning, and the Giants went on to sweep the Indians in four games to capture the World Championship.

Though the Giants would not return to the postseason while in New York, Mays continued to be a human highlight reel, finishing in the top six of the MVP voting eleven of the next twelve years. He led the major leagues in home runs, triples, and slugging percentage in 1955. In 1956, he became the first player in 34 years to hit over 30 home runs and steal over 30 bases in a single season; he repeated the feat the following year, effectively creating what has become known as the “30-30 club”. At different times over the course of his career, Mays led the league in a staggering eleven different offensive categories. When Rawlings introduced its Gold Glove award in 1957, Mays was one of its first recipients; he went on to have a virtual lock on the award for the next 12 years.

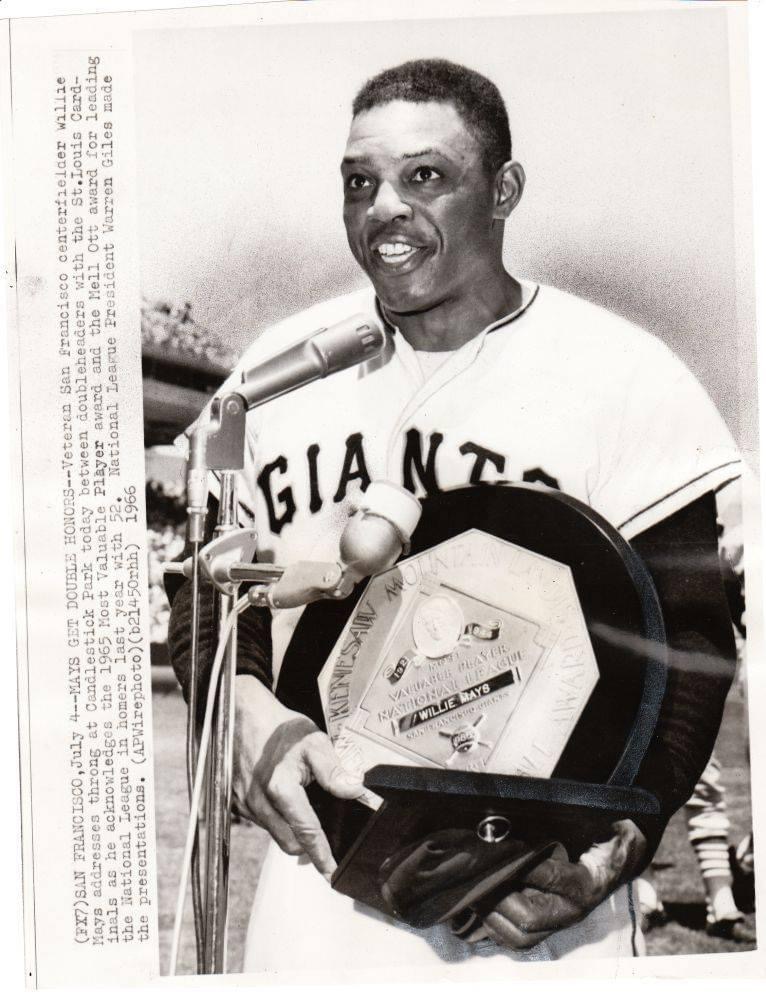

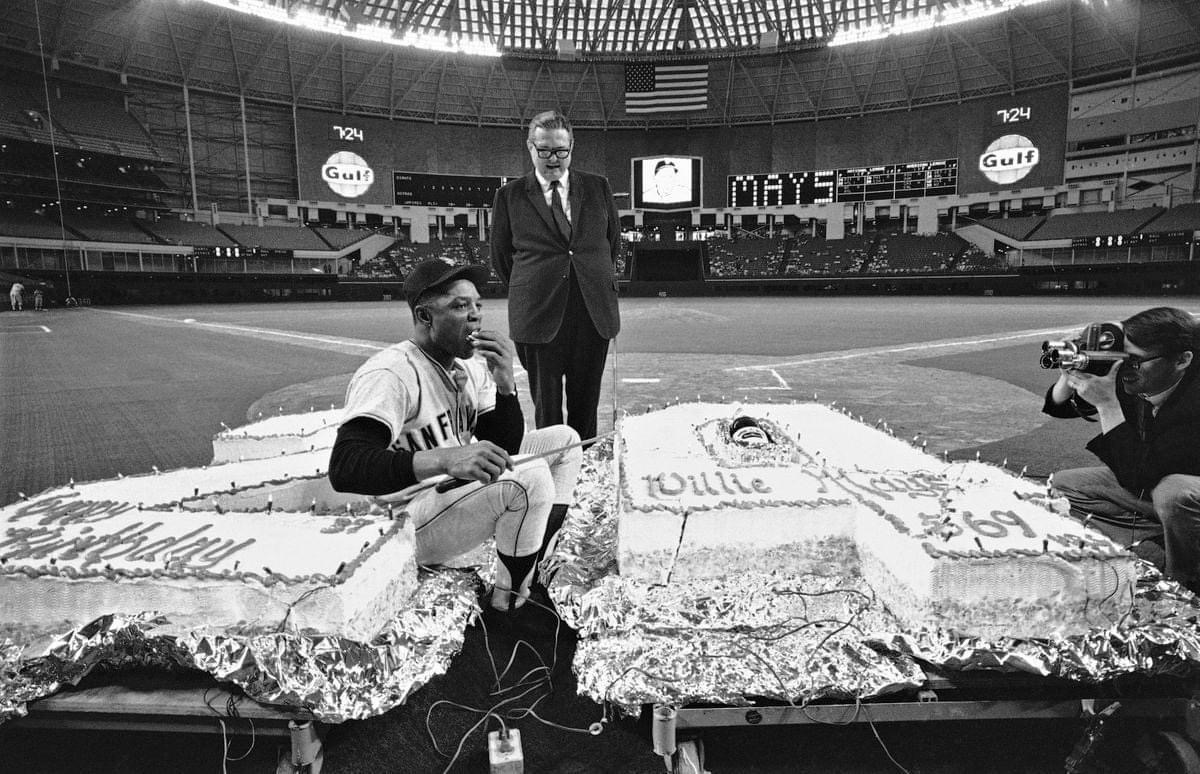

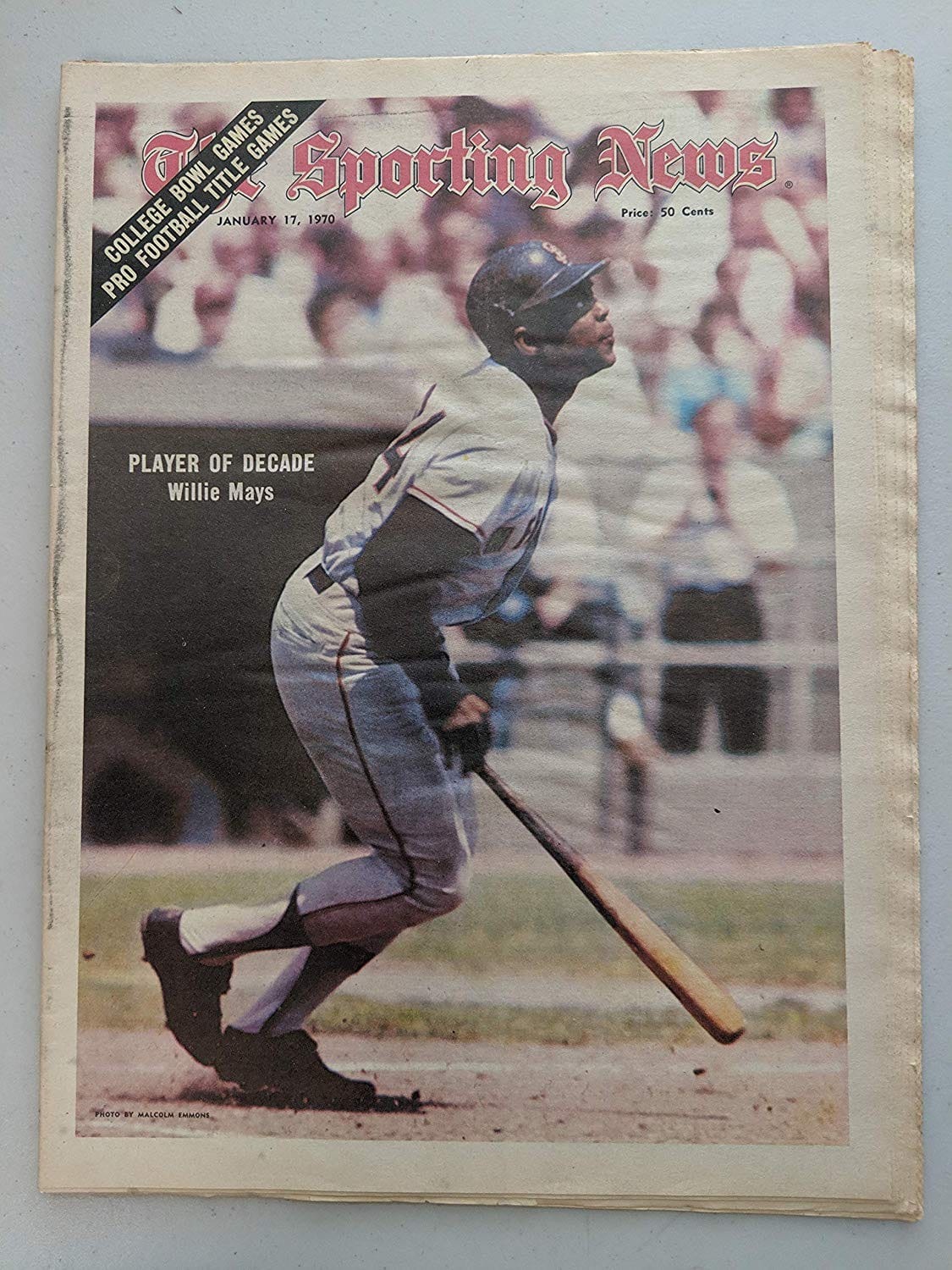

Plagued by sagging box office receipts in their final years at the Polo Grounds, the Giants relocated to San Francisco in 1958. Mays, who had flourished in Harlem, found the transition to West Coast life difficult at first, but he didn’t allow his personal problems to affect his play. He finished second in the NL batting race in 1959, losing the title to Richie Ashburn on the last day of the season. In 1961, Mays became only the ninth player in baseball history to hit four home runs in one game, and he finished the year with 40. He reached the 40 home run mark again the following year, leading the league with 42, and leading his team to another World Series appearance. The Giants, though, lost a dramatic series to the Yankees in seven games. Mays had arguably his best season three years later, when he led the league with a career-high 52 home runs; he also led the majors in slugging, on-base percentage, and total bases to earn his second MVP award. After Mays hit his 600th home run in 1969, The Sporting News honored him as its player of the decade; in later years it named him the second-greatest player of all time, right behind Babe Ruth.

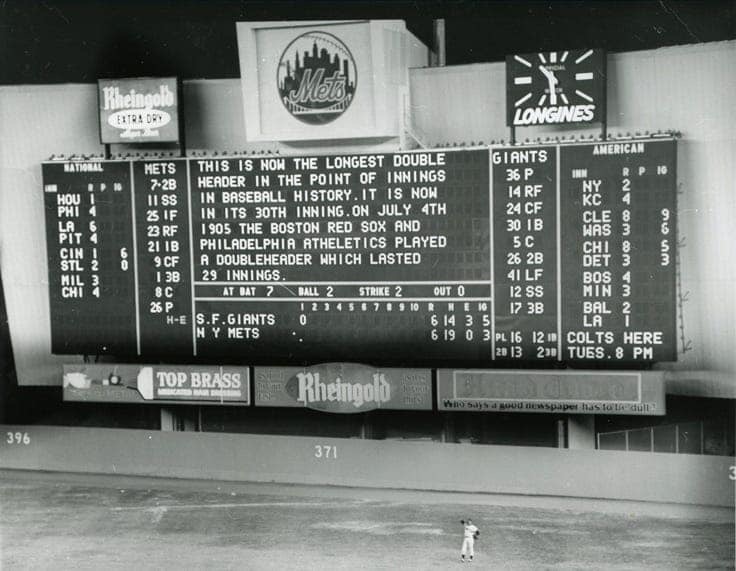

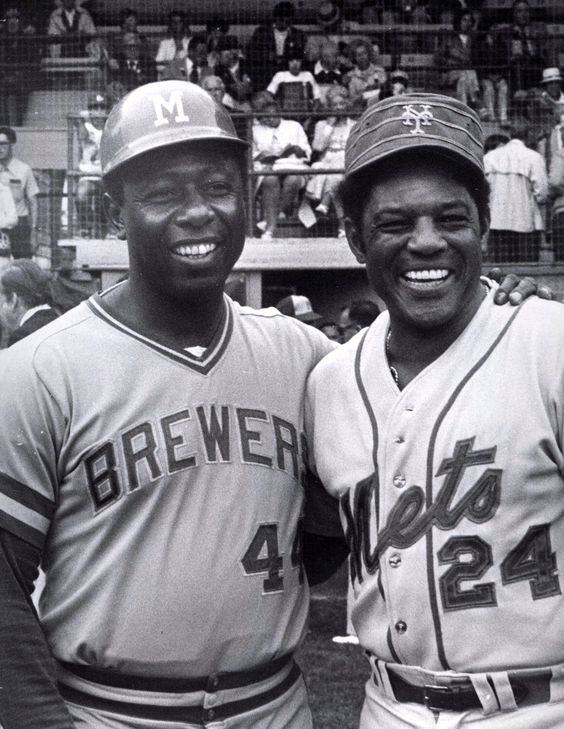

As the 60’s gave way to the 70’s, age and injuries started to catch up with the seemingly ever-youthful Mays, who at this point was the oldest player in the major leagues. After a sub par 1971 season, the cash-strapped Giants traded Mays to the New York Mets for pitcher Charlie Williams and cash considerations. Mays welcomed the return to his baseball roots, and he was warmly greeted in New York, where he had remained popular even after the move to San Francisco. Mays homered in his first game as a Met but, hobbled by knees that needed to be routinely drained of fluid, he was limited to part-time duty. He struggled early in the 1973 season, as did the Mets, but both recovered by season’s end, enabling New York to snatch the NL pennant from the powerful Cincinnati Reds. The once fleet-footed Mays subsequently struggled in the outfield during the World Series, but he stroked the game-winning hit in Game 2. The Mets lost the close Series to the Oakland Athletics in seven games, and, in spite of pleas from his fellow players, Mays retired after the season.

Mays stayed on with the Mets as a hitting instructor until 1979, when he was elected to the Hall of Fame in his first year of eligibility with 95 percent of the vote. Later that year, he accepted a position as a greeter and public relations representative for Bally’s Casino in Atlantic City, N.J. Though his contract with the casino prohibited him from any gaming activity, commissioner Bowie Kuhn still viewed it as a violation of Major League Baseball’s rules against gambling, and he suspended Mays and Mickey Mantle (who held a similar position) indefinitely. Kuhn’s successor, Peter Ueberroth, rescinded both suspensions in 1985, citing both players’ importance to the game and its history.

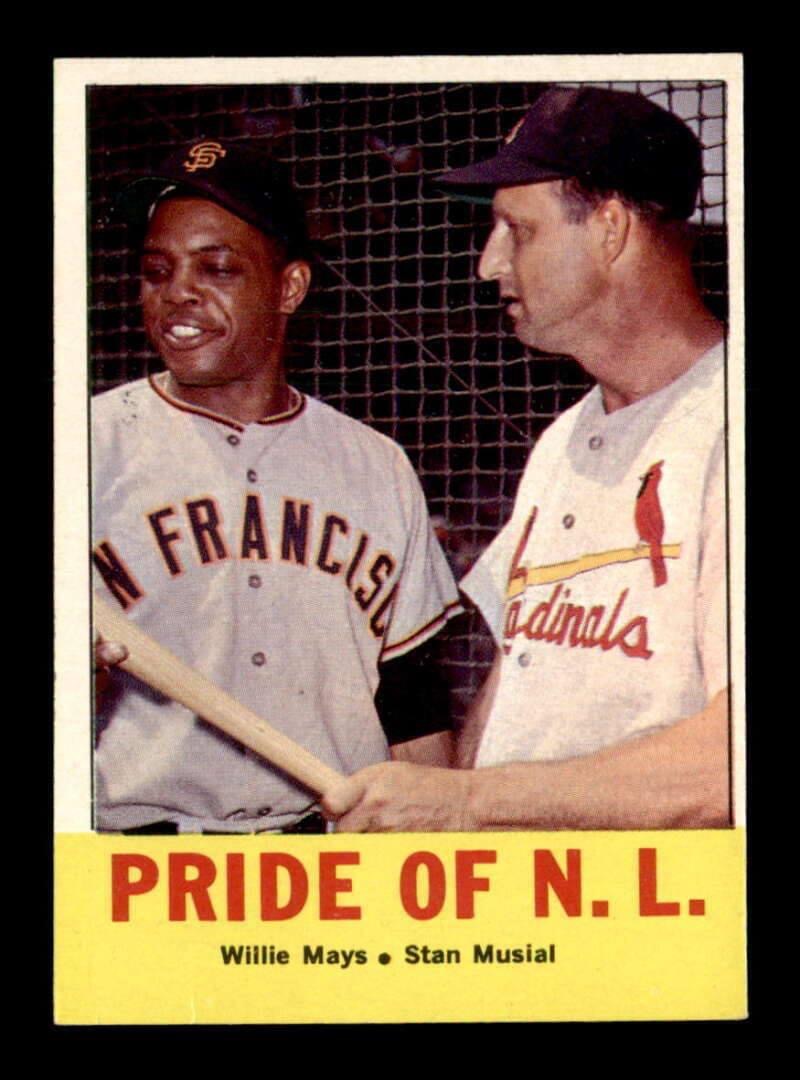

In the years since, Mays’ stature has risen to that of a storied folk hero; he is widely recognized as a national treasure and a cherished link to baseball’s, and America’s, golden past. He has been honored by the city of San Francisco and the state of California numerous times, and he has received honorary doctorates from Yale, Dartmouth, and San Francisco State University. The Giants’ new home, SBC Park, is located at 24 Willie Mays Plaza; a statue of Mays, ringed by 24 palm trees, greets fans at the stadium’s entrance. It depicts Mays, fittingly, in motion, busting out of the batter’s box following one of his 3,283 hits. But the greatest tribute to Mays can be found in the testimonials of his fellow players; no less than Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, and Stan Musial (among many others) identified him as the greatest player each had ever seen. Before Willie Mays, only Babe Ruth had been as uniquely gifted and universally beloved, and it is possible that the game, or the world of sports beyond, shall never see his like again. As baseball scribe Ray Robinson once wrote, “It’s possible that no athlete in any sport can ever again mean to us what Willie Mays once meant.” For now, he is arguably the game’s greatest living player, and one of its most affable ambassadors.

@ET-DC@eyJkeW5hbWljIjp0cnVlLCJjb250ZW50IjoicG9zdF90YWdzIiwic2V0dGluZ3MiOnsiYmVmb3JlIjoiTGVhcm4gTW9yZSBhYm91dCB0aGUgdGVhbXMsIHBsYXllcnMsIGJhbGwgcGFya3MgYW5kIGV2ZW50cyB0aGF0IGhhcHBlbmVkIG9uIHRoaXMgZGF0ZSBpbiBoaXN0b3J5IC0gLSAtIC0gLSAtIC0gIiwiYWZ0ZXIiOiIiLCJsaW5rX3RvX3Rlcm1fcGFnZSI6Im9uIiwic2VwYXJhdG9yIjoiIHwgIiwiY2F0ZWdvcnlfdHlwZSI6InBvc3RfdGFnIn19@

Factoids, Quotes, Milestones and Odd Facts

Played For

New York Giants (1951-1957)

San Francisco Giants (1958-1972)

New York Mets (1972-1973)

Similar: Ken Griffey Jr. has some similarities and so does Andruw Jones, but there’s no one truly comparable to Willie Mays… A few of the players who were compared to Mays: Mickey Mantle, Duke Snider, Frank Robinson, Vada Pinson, Bobby Bonds, Cesar Cedeno, Barry Bonds, Ken Griffey Jr., Andrew Jones

Linked: Mickey Mantle, Duke Snider, Bobby Bonds, Barry Bonds

Best Season, 1954

It all depends on which Mays you want – the young speedster who stole bases or – the older slugger who still ran well and fielded like a champ. I chose 1954 primarily because he was still swiping some bases (24 in 28 tries) and his team won the World Series largely because of him. He led the NL in batting, slugging, triples, runs created, OPS, and TA. He belted 41 homers and had a .415 OBP. In the World Series his catch of Vic Wertz’s deep drive won the opener. He was a young lion in 1954 with many more great years ahead.

Awards and Honors

1951 NL Rookie of the Year

1954 NL MVP

1957 ML Gold Glove

1958 NL Gold Glove

1959 NL Gold Glove

1960 NL Gold Glove

1961 NL Gold Glove

1962 NL Gold Glove

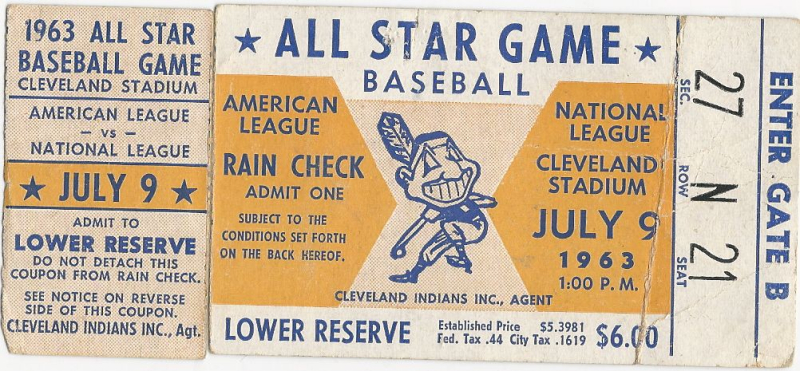

1963 ML AS MVP

1963 NL Gold Glove

1964 NL Gold Glove

1965 NL Gold Glove

1965 NL MVP

1966 NL Gold Glove

1967 NL Gold Glove

1968 ML AS MVP

1968 NL Gold Glove

Post-Season Appearances

1951 World Series

1954 World Series

1962 World Series

1971 National League Championship Series

1973 National League Championship Series

1973 World Series

Description

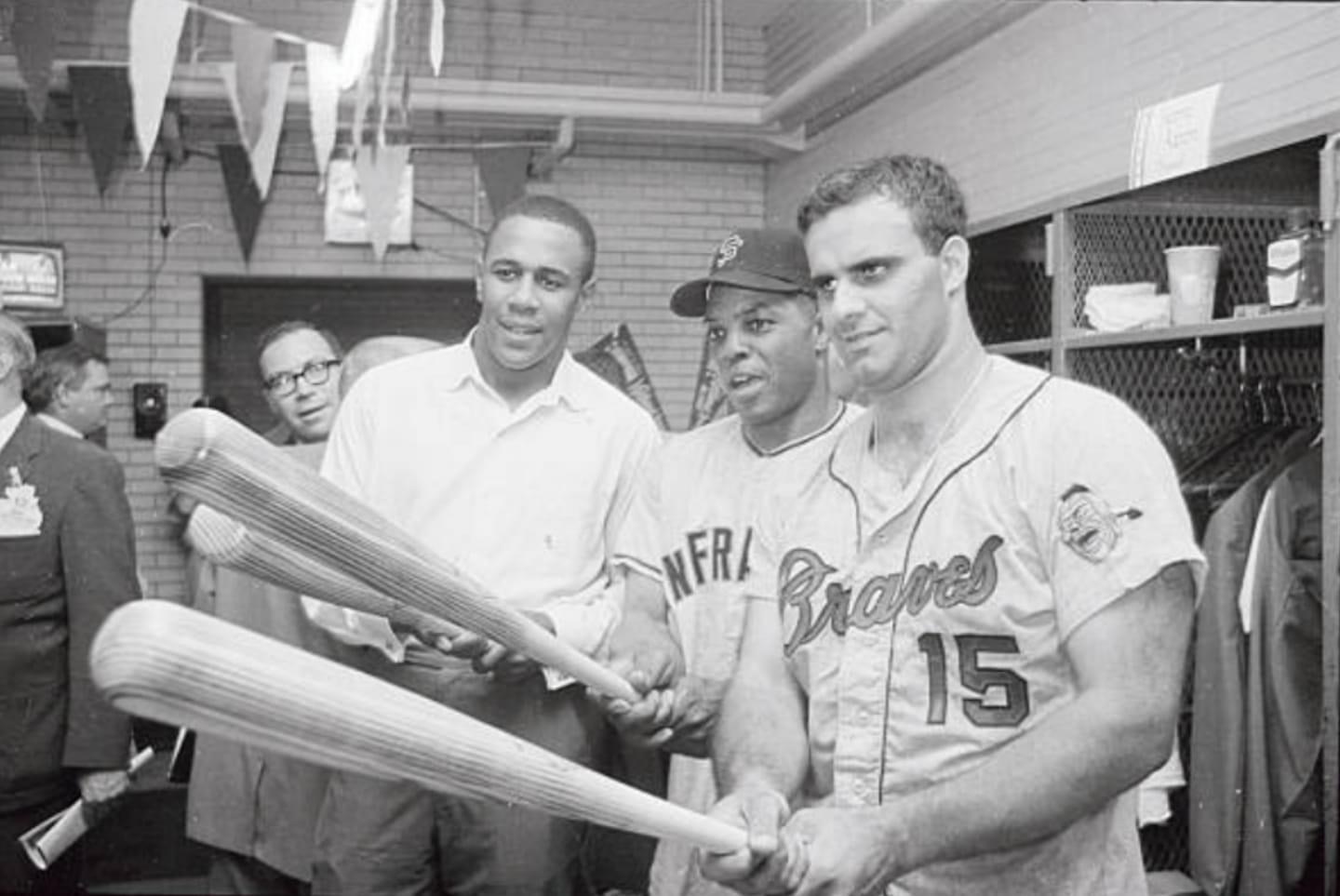

Mays still garners consideration by many as the greatest player of all-time. He was the original “five-tool player,” possessing the ability to hit, hit for power, run, throw, and field. He retired with 660 home runs, but he was far more than a slugger. He swiped more than 300 bases and was the best defensive center fielder of his era. Mays deserves his ranking as one of the game’s elite superstars. As a young player, Mays was fun-loving and gregarious, earning the nickname “Say Hey” for his catch-phrase at the ballpark. He was known to frequent the streets of New York, playing stickball with children and handing out his autograph. As he grew older, and after the Giants moved to San Francisco, Mays cooled to the media and became more aloof. As he began to pile up home runs, it was Mays, not Aaron, who was seen as the threat to Babe Ruth’s record. Eventually, it was Mays’ bad legs that kept him from breaking the mark. Mays was lalmost universally loved by his teammates, and he often helped younger players become acclimated to the big leagues. Mays tutored Bobby Bonds, who later made Mays his son’s godfather. That son became Barry Bonds. Mays was a tremendous athlete, and perhaps his baseball skills can best be summed up in the fact that from 1957-1966, he finished no lower than sixth in NL MVP voting every year. He won the Award twice and became the first player to reach 3,000 hits and 500 homers.

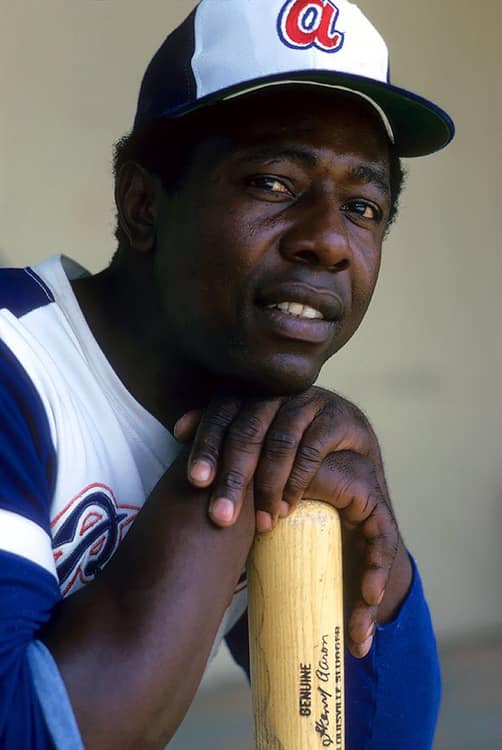

Feats: Willie Mays, Hank Aaron, Eddie Murray and Rafael Palmeiro are the only players to collect both 500 homers and 3,000 hits.

Notes

Mays is one of the few players to hit four homers in a game… He accumulated twenty steals and homers in the same season six straight years.

Hitting Streaks

21 games (1954)

21 games (1957)

21 games (1954)

21 games (1957)

20 games (1964)

20 games (1964)

18 games (1965)

18 games (1965)

Transactions

Signed as an amateur free agent by New York Giants (1950); traded by San Francisco Giants to New York Mets in exchange for Charlie Williams and $50,000 (May 11, 1972).

Quotes About Mays

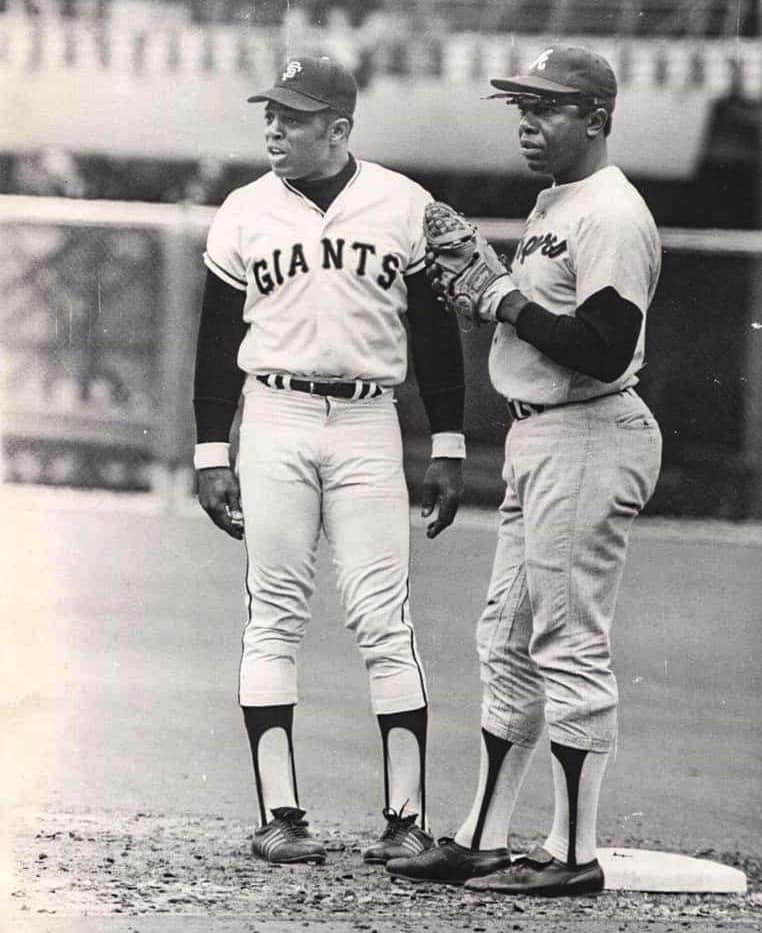

“I’ve played with him and against him, and as far as I’m concerned there never could have been any better center fielder.” — Red Schoendienst on Willie Mays

“Willie Mays was the finest player I ever saw, make no mistake about it. He could carry a team for a month at a time by himself. But, because he was so skilled, he was able to get away with a lot of things he did wrong on the field, and it was hard for him to show the younger players how to get the job done.” — Willie McCovey

Quotes From Mays

“I don’t know why they call me that. I don’t ever get excited. I just play my game and let others get excited.” — Willie Mays in 1957, when told he was considered the most exciting player in the game.

Wait, Wait, Swing!

According to experimenst done on his swing, Mays was .05 seconds faster than other hitters, giving Willie nearly 20 percent longer to wait on a pitch. Therefore, he was able to delay his swing until the ball was six feet closer to the plate than most other hitters.

All-Star Selections

1954 NL

1955 NL

1956 NL

1957 NL

1958 NL

1959 NL

1960 NL

1961 NL

1962 NL

1963 NL

1964 NL

1965 NL

1966 NL

1967 NL

1968 NL

1969 NL

1970 NL

1971 NL

1972 NL

1973 NL

Replaced

The 1951 Giants had a huge hole at first base. So they moved left fielder Whitey Lockman to first, which opened one spot the outfield. A second spot was opened when the 1950 center fielder, Bobby Thomson, moved to third base and was supplanted by Mays. Monte Irvin, Lockman and Thomson shared left field.

Replaced By

Mays was traded to the Mets in 1972, opening the way for Garry Maddox in center field. With the Mets, Mays was never a full-time player.

Best Strength as a Player

Combination of speed and power.

Largest Weakness as a Player

He had no weakness as a ballplayer.

Other Resources & Links